Hemingway vs. Fitzgerald: The Rise and Fall of a Literary Friendship

by Scott Donaldson

Chapter 11

The Master And The Actor

People like Ernest and me were very sensitive once and saw so much that it agonized us to give pain. People like Ernest and me love to make people very happy, caring desperately about their happiness. And then people like Ernest and me had reactions and punished people for being stupid, etc., etc. People like Ernest and me…

—F. Scott Fitzgerald, Notebooks

It is hard to take the note above any way but ironically. The first sentence makes some sense, for only two writers of great sensitivity could have produced the wonderful fiction of the 1920s and 1930s. But it was Scott who cared desperately about making other people happy, including Hemingway, and Ernest who punished others, including Fitzgerald, for their stupidity. “People like Ernest and me” presupposes a likeness between the two men that simply did not exist. They could hardly have been more different.

It was the difference that made the quirky and difficult relationship possible, and that converted it finally into an exercise in sadomasochism. Hemingway felt a compulsion to dominate, to lord it over others, and Fitzgerald had a complementary need to be dominated. If Ernest liked to kick, Scott wore a sign on his backside saying “Kick Me.” In a piece of light verse, Theodore Roethke captured something of this intermixture of psychological shortcomings:

It wasn't Ernest; it wasn't Scott—

The boys I knew when I went to pot;

They didn't boast; they didn't snivel,

But stepped right up and swung at the Devil…

Roethke knew his readers would understand who did the boasting, who the sniveling.

In an important article, Ruth Prigozy examined the psychodynamics of the Fitzgerald-Hemingway relationship. Leaving aside the issue of rivalry, she suggested that they responded to each other on the basis of “mutual personal need.” Fitzgerald, in his boyish romanticism, found an embodiment “for his dreams of personal heroism and physical superiority” in Hemingway. As he wrote in his notes, when he liked men he wanted to be like them, to absorb into himself those qualities that made them attractive. In the attempt to achieve this impossible goal, he was willing—more than willing—to abase himself before the objects of his hero worship, courting “humiliation as others did success” and in the process gratifying “his own self-destructive impulse, his perverse need for punishment.”

Hemingway was put off by the fulsome admiration Fitzgerald lavished upon his work at their first meeting. Praise to the face, he felt, was open disgrace. Later, he repudiated the role of being “Scott's bloody hero” as “embarrassing.” In fact, Hemingway was embarrassed by all public displays of feeling, considering them demonstrations of weakness or effeminacy. In Fitzgerald, Prigozy proposed, he located an alter ego, a repository for his own “very real insecurities and sexual worries.” Consciously or not—and Prigozy thinks Fitzgerald intuitively understood the situation—Scott became “outwardly the walking model of Hemingway's fears, the symbol of his despair.” By attacking Scott, Ernest tried to dispose of those fears.

This view of the Fitzgerald-Hemingway connection does not, of course, address the sources of the feeling between them, nor does it minimize the genuineness and depth of that feeling. Even in his ill-spirited assaults after Fitzgerald's death, Hemingway repeatedly proclaimed that he spoke out of love. The usual formulation followed the “I loved Scott, but…” pattern. “We both loved him,” he wrote to Perkins, “I cared for Scott so much” to Wilson. Readers might be inclined to take such statements with a grain of salt, inasmuch as they were customarily followed by derogatory comments. On the other hand, it was extremely difficult for Hemingway to confess his love for anyone. I know of no other man that he said he loved. Certainly there is no one he said he loved as often and as openly as he did of Fitzgerald. And Fitzgerald said the same thing about Hemingway, even after the abuses Ernest visited upon him in “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” and elsewhere. No matter what he did, “[s]omehow I love that man,” he wrote Perkins. He confessed that love in his notebooks, as well. As Wilson summed up the situation, Scott “began by adoring” Ernest and “remained more of less obsessed by him” all his life.

That Hemingway and Fitzgerald loved each other does not provide a warrant for the assertion that they were lovers. Only Zelda Fitzgerald, among those who knew them, ever proposed that possibility, and Zelda made her accusation at a time when she felt a strong sexual attraction to another woman and may have wanted to ameliorate her own feelings of guilt.

In his public persona as in his (mostly posed) photographs, Fitzgerald appears as an elegant young man—fine-featured, well-dressed, well-mannered, charming, clever, and romantic, if unfortunately afflicted by alcohol and victimized by fate. For the Triangle Club show “The Evil Eye,” his photograph was taken in drag and circulated as a picture of Princeton's “most beautiful showgirl.” (At the time, there were no female undergraduates, and their roles were played by men.) With “a touch of the feminine” in his nature, Fitzgerald possessed an unusual capacity to put himself in the shoes of his fictional women.

Hemingway's public image, on the other hand, bears an unmistakably masculine cast. He is ruggedly handsome, decked out in outdoor gear, and wearing a signature beard. The precise details of Fitzgerald's appearance are somewhat hazy in the public imagination, but everyone knows what Hemingway looks like: so much so that there is an annual contest in Key West for Hemingway look-alikes. His reputation as sportsman and warrior—as an outdoorsman who managed to do some writing—appealed to the anti-intellectual strain in the American imagination. At the same time, however, it stigmatized him as egregiously macho.

Octavio Paz construed the typical macho figure as a stoical man capable of bravery and endurance in the face of adversity, much like such Hispanic heroes in Hemingway's fiction as the bullfighter Manuel Garcia in “The Undefeated” and the fisherman Santiago in The Old Man and the Sea. Hemingway aspired to such behavior himself, and at times succeeded, as under fire during World War II. But he also resembled the prototypical macho in another and more important way. Such a man, Paz wrote, is “a hermetic being, closed up in himself,” for to open himself to others would both demonstrate weakness and invite rejection. The stereotyping of Hemingway has concentrated on his aggressively masculine appearance and pursuits, and not taken his psychologically withdrawn side into account. He was macho all right, but in a different way than most observers think.

In the light of these public perceptions of the two men, and of their fiction, it is somewhat surprising to discover a fascination with unconventional sexual arrangements permeating the work of Hemingway. Living in Paris in the early 1920s, he met and befriended a number of independent and sexually liberated women, mostly lesbians. These included not only Stein and Toklas, but also Sylvia Beach, Natalie Barney, Margaret Anderson, Bryher (Winifred Ellerman), and Janet Flanner. Hemingway made fewer such friends among the gay male community of the Left Bank. To do so would have been to invite speculation about his own orientation. But he did of course observe, and depicted both gays and lesbians in some of his early fiction, as for example in “The Battler” (probably), “A Simple Enquiry,” “The Mother of a Queen,” and “The Sea Change.”

In Paris, too, he encountered the New Woman, or her reasonable facsimile in the liberated person of Lady Duff Twysden, a woman who took on and disposed of lovers as casually as a male Lothario. In her fictional form as Lady Brett Ashley in The Sun Also Rises, this dangerous creature succeeded, Circe-like, in transforming the men around her into swine, without herself gaining the least glimmer of happiness. “Promiscuity no solution,” Hemingway noted. But Lady Ashley remained a basically sympathetic character on the page, reflecting Ernest's own feelings about Duff. Throughout his early fiction, and particularly in the stories of love and marriage in disrepair, his sympathy seems to reside with the female characters—the neglected wife in “Cat in the Rain” and the woman reluctant to undergo an abortion in “Hills Like White Elephants,” for example.

As many have noticed, there are few truly successful man-and-woman relationships in the fiction of Ernest Hemingway. In stories that look back to his own parents, women dominate and emasculate their husbands, like Mrs. Adams in “The Doctor and the Doctor's Wife” and “Now I Lay Me.” In stories that deal with figures contemporaneous with himself, young men resent or resist the marital commitments that get in the way of their doing what they like to do— skiing, fishing, traveling around Europe without undue encumbrances. When Hemingway does invent an apparently idyllic love, as in A Farewell to Arms and For Whom the Bell Tolls, death soon intervenes to bring it to an end.

The very absence of successful lasting relationships, Rena Sanderson believes, suggests an implicit yearning for them. In effect, Hemingway posits an ideal prelapsarian world where a man and a woman are united against the rest of the world. Hemingway's stories are full of the problems that get in the way of such an idyllic state, among them “homoeroticism, divorce, abortion, venereal disease, infidelity.” But as Sanderson points out, the greatest single problem is male passivity, as in the various self-abasements Jake Barnes undergoes for Brett and the humiliations Dr. Adams silently accepts from his wife.

The most vivid and compelling portrait of such a man comes in the 1936 story “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber,” where the title figure—a wealthy and weak character who is good at court games but little else—undergoes a series of mortifications during an African safari. After he runs from a charging lion in full view of his beautiful wife, Margot, she exacts a double vengeance upon him. She taunts him cruelly in the presence of white hunter Robert Wilson, and then cuckolds him with Wilson, despite having promised that “there wasn't going to be any of that” on safari. These events lead Wilson, who carries a double-sized cot to take advantage of any such “windfalls,” to reflect on relations between American women and their husbands in an extremely misogynistic passage.

They are, he thought, the hardest in the world; the hardest, the cruelest, the most predatory and the most attractive and their men have softened or gone to pieces nervously as they have hardened. Or is it that they pick men that they can handle?

However it may have begun, the marriage of the Macombers degenerated into the worst of accommodations. “They had a sound basis of union. Margot was too beautiful for Macomber to divorce her and Macomber had too much money for Margot ever to leave him.” But the wife must maintain the upper hand. At the end of the story, when in his fury at her infidelity Francis bravely confronts a wounded buffalo, Margot shoots him dead. Whether accidentally or on purpose is left ambiguous, although Hemingway commented twenty years later that, in his experience, the percentage of husbands killed accidentally by bitchy wives was very low.

Hemingway's misogynistic tendencies peaked during the 1930s, following the suicide of his father and his own marriage to a woman who—like Helen in “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” a companion story to “Macomber” published in the same year—was rich enough to support him. Thereafter they receded in his fiction, if not entirely in his life. Among the papers Hemingway left behind in his Cuban home was a fragment generalizing about the fitness of women as wives for male writers. Women can be wonderful friends, the passage reads, but also make dreadful enemies. They break the rules: “Woman is the only two legged animal that stands upright and will always hit after the bell.” They always have to be jealous, “and if you give them no cause for jealousy except your work they will be jealous of that.” They are far more interested in your ability to fuck than your ability to write. They are greedy, and will “remember for a hundred years any cashable asset they did not get” from their husbands. You must never say anything against a woman's family,but also never agree with anything bad she may say about it. Still, real bitchery was abnormal. “Most lovely women bat over .750 at not being bitches.”

Such reflections conform to the public perception of Papa Hemingway as a man's man more comfortable on the Gulf Stream than in the bedroom. But that image was severely challenged in the posthumously published The Garden of Eden (1986). A novel of 250 pages cobbled together from a manuscript several times that length, Garden tells the story of David Bourne and his erotically adventurous wife, Catherine, who draws him into cross-sexual roles. In bed, for example, she mounts him, calling herself “Peter” and him “my girl Catherine.” Subsequently, both David and the devilish Catherine make love to the bisexual Marita, forming an uneasy ménage à trois. At the end, after the mentally disturbed Catherine has burned her husband's manuscripts, David is living contentedly with Marita, his capacity to write having survived the destructive yet oddly invigorating effects of the sexual experimentation.

More than any other book put together from Hemingway's voluminous manuscripts, The Garden of Eden stimulated a critical re-examination of his work. Several of the themes it explored—male androgyny, female madness, unconventional sexual behavior, and the relationship between sex and creativity—were at least implicitly present in his previous writing. Consider, for example, the erotic role that haircuts play in Hemingway's fiction, most notably in A Farewell to Arms. Catherine Barkley proposes to Frederic that she cut her hair and he grow his so they will look alike. It will give them something to do while they await her baby, she suggests, and he happily assents. A similar scene is enacted in the first chapter of Garden, though it was omitted from the published version by editor Tom Jenks of Scribner's. Catherine Bourne goes to the barbershop in order to bring back to David a “dangerous” surprise: hair cut to precisely his length. He then dyes his hair blond to look like hers and the two of them take the sun for identical tans, in order to become “the same one” (as Catherine Barkley remarked) and/or to eradicate gender distinctions in lovemaking.

As J. Gerald Kennedy has discovered, Hemingway wrote a very similar haircut scene in a chapter cut from A Moveable Feast, which he was composing more or less simultaneously with The Garden of Eden in the late 1950s. This nineteen-page sketch focused on Ernest and Hadley after their return to Paris in 1924. They had their own private customs at the time, Hemingway wrote, their own standards and taboos and delights. One such delight came when they agreed on an androgynous project of identical hairstyles. He would grow his out, and she'd get hers evened and wait for him to catch up. It would probably take four months, Hadley estimated.

“Four months more?”

“I think so.”

We sat and she said something secret and I said something secret back.

“Other people would think we are crazy.”

“Poor unfortunate other people,” she said. “We'll have such fun Tatie.”

“And you'll really like it?”

“I'll love it,” she said. “But we'll have to be very patient. The way people are patient with a garden.”

When she returned from the hairdresser's to show him her newly cut hair, Hadley said, “Feel it in back,” the exact words Catherine utters to David in the opening chapter of Garden. And when he did so, his fingers shaking, she commanded him to “[s]troke it down hard.” Again he said “something secret” as he held his hand against the silky weight of her hair. “Afterwards,” she said.

Ernest played similar sexual games, involving hair and role-changing, with his fourth wife Mary. She was “Pete,” he was “Catharine.” Mary had no lesbian leanings, but always wanted to be a boy, he wrote in December 1953. Though he disliked all tactile contact with other men, embracing Mary introduced him to “something quite new and outside all tribal law.”

In Feast as in Garden, then, Hemingway revealed the excitement he felt about crossing the conventional boundaries between men and women. Yet there was every good reason for him to excise the passage about unisex hairstyles from A Moveable Feast, a memoir in which he consistently portrayed the protagonist—a young writer named Ernest Hemingway—as a figure of strictly conventional sexual orientation who regarded gay men with derision and lesbians with disgust. In The Garden of Eden, which he had no plans to publish, he could more freely explore what Kennedy calls “the unstable terrain of sexual ambivalence.” After the appearance of Garden in 1986, it became clear that Hemingway's feelings about sex, like everything else about him, were too complicated to conform to a simple macho image. Scholars began to write books about Hemingway's battle with or immersion in androgyny. “The Hemingway you were taught about in high school,” Nancy Comley and Robert Scholes announced, “is dead.”

Fitzgerald could never have written about, or even conceived of, an arrangement like that of the Bournes and their mutual lover Marita in Garden. His attitudes toward sex were rigorously traditional, the product of his midwestern Catholic upbringing, and he felt a visceral abhorrence toward homoerotic relationships. The story that fascinated him, because it was so nearly his own, was that of the young man rejected by a beautiful and desirable young woman of higher social status. He saw such encounters as part of a game—later, a war-that the poor young man could not hope to win.

This is precisely the situation of Amory Blaine and Rosalind Connage in This Side of Paradise. Rosalind, a New York debutante, plays off one beau against another as she moves toward a decision about who to marry. She is in control of these relationships, throughout. “Given a decent start,” she asserts, “any girl can beat a man nowadays”—and with her beauty and wealth she has been given far more than that. Following the advice of her mother, Rosalind decides to turn down Amory in favor of a rival who can promise her a future to compare with her privileged past. Her love for Amory cannot make up for what she stands to lose should they marry. As she tells him, “I like sunshine and pretty things and cheerfulness—and I dread responsibility. I don't want to think about pots and kitchens and brooms. I want to worry whether my legs will get slick and brown when I swim in the summer.”

Fitzgerald does not condemn Rosalind for her hard-hearted if sensible choice, any more than he could condemn Ginevra King for making the same choice. At a time when prospects of a career were minimal and divorce carried a definite stigma, young women were hardly to be faulted for following a course of economic and social security. Instead of blaming Ginevra for rejecting him, or Rosalind for rejecting Amory, Fitzgerald continued to put these golden girls on a pedestal because of their unavailability. If the male protagonists of his fiction lost the game, at least they could keep their illusions. This placed the women in his fiction, and in his life, in an untenable position. They could only preserve their status as idealized creatures by repudiating the love of their suitors, as Daisy turned down Gatsby. The issue of social class is central in that novel as in many of the stories. The two characters who dare to fall in love above their station— Gatsby and Myrtle Wilson—end up dead, while Tom and Daisy Buchanan safely retreat into their money and their “vast carelessness.”

On the other hand, should such a desirable woman elect to marry one of Fitzgerald's male protagonists, the marriage was usually compromised by the “fine, full-hearted selfishness” characteristic of a Rosalind or of a Judy Jones (in “Winter Dreams”) or, as Scott maintained, of his wife Zelda. In “The Adjuster,” a story published like Gatsby in 1925, Fitzgerald dramatized the difficulties confronting Charles Hemple, who cracked under the strain of supporting all the responsibilities of the household while his wife Luella pursued various avenues of excitement. Otherwise Charles was strong and capable: his attitude toward his wife was hisweak point. “[H]e was aware of her intense selfishness, but,” the author intrudes to comment, “it is one of the many flaws in the scheme of human relationships that selfishness in women has an irresistible appeal to many men,” particularly when accompanied as in the case of Luella Hemple by “a childish beauty.”

The irresponsible and narcissistic (if still somehow enchanting) belle of Fitzgerald's early fiction grew into the more dominant and independent woman of his later work. In good part, the changing situation in his fiction was a response to the cultural revolution in morals and manners. In a 1930 essay, Fitzgerald announced the arrival of the independent woman. The flapper had been replaced by “the contemporary girl,” who possessed courage as well as beauty and radiated poise and self-confidence. In a rather frightening development, she had also become sexually liberated and no longer identified virtue with chastity. Fitzgerald expected wonders from this newly independent woman. It was “the poor young man” he worried about.

In Tender Is the Night, this confident new woman engaged the young man he worried about in a dramatic struggle, and emerged victorious. In portraying Nicole Diver's progress from dependent mental patient to a woman sure of her ground and hard as Georgia pine, ready to discard her husband Dick to take on a lover—Why not? she thinks, other women do—Fitzgerald was developing on the page some of his own fears about the battle of the sexes.

Here he was influenced by his reading, in 1930, of D.H. Lawrence's Fantasia of the Unconscious. In Lawrence's view, contemporary man was losing sight of his principal objective in life—a “disinterested craving… to make something wonderful” of himself—as a consequence of his sexual desire. Trying to please the female led to weakness in males, Lawrence believed, and the modern woman filled the vacuum, becoming “a queen of the earth, and inwardly a fearsome tyrant.” These ideas fitted into Fitzgerald's own concept of a deadly competition between the sexes, and his apprehension that the women were winning.

His private life was very much on his mind in this connection. In Tender, Nicole Diver recovers her strength while Dick suffers a moral, physical, and professional decline. It was as if she drew health and energy from her husband, leaving him depleted. By 1932 or 1933, Fitzgerald became convinced that he and Zelda were engaged in a marital war from which only one of them would emerge whole. In a document among his notes, he even envisioned a diabolical plot to “attack on all grounds,” driving Zelda further into madness by suppressing her creative work, disorienting her schedule, and detaching her from Scottie.

Tender Is the Night contained Fitzgerald's frankest and most antagonistic portrayais of homoerotic characters, both gays and lesbians. He became closely acquainted with this subculture during the late 1920s in Paris, some years after Hemingway, and responded to it with abhorrence. A section excised from Tender makes a stronger statement of repulsion than anything in the published novel. Francis Melarkey, the hero of the novel (in its first draft), is attracted to Wanda Breasted. He meets her at a bar where three tall, slender women make slurring remarks about Seth and Dinah Piper (the original names of the Divers). Annoyed by these insults to friends of his but with expectations of a tryst with Wanda to follow, Francis joins her on a drinking spree. His hopes are dashed when he finds her in the embrace of another woman, but he extricates Wanda, takes her home, and stays with her after she threatens suicide. It is morning before he can escape. “Good God, this is getting to be a hell of a world,” he thought. “God damn these women!”

Love does not work out for Hemingway's characters because the fates are against them. There are no lasting marriages in his fiction. Death intervenes when they threaten to develop, as for Catherine Barkley or Robert Jordan. You cannot go back to a prelapsarian Garden. Love doesn't lead to happy endings for Fitzgerald's characters, either, though for different reasons. In his universe, love can only endure if the lover is rejected by the object of his love, who thus preserves her status as an idealized object. Let the two marry, and the illusions that make the love possible will inevitably vanish, leading at best to the disillusionment or—in Fitzgerald's later fiction—to the destruction of the lover.

The relationships that failed in the stories and novels of Hemingway and Fitzgerald were paralleled in their lives. Hemingway, who was married four times, broke off the first three marriages himself and tried to break off the fourth. Fitzgerald was married only once, but his union with Zelda was far from happy. If love could not last for either of them, neither could friendship.

Psychological Speculations

In the end is my beginning… The end is where we start from.

—T.S. ELIOT, “Four Quartets”

In The Psychopathic God: Adolf Hitler, Robert G.L.Waite attempted to combine the techniques of psychological investigation with the rigorous findings of history.He was aware of the danger that such an approach might reduce “complex personalities” to a mere diagnosis, while historical scholarship argued for multiple causation. But Waite also pointed out what the psychologist Erik Erikson had to say on the subject: that those very biographers who categorically repudiated systematic psychological interpretation nonetheless permitted themselves “extensive psychologizing” justified in the name of “common sense.” Whenever the question “Why” intruded itself, some sort of psychological explanation was sure to follow.

Well, then, why? What was there about Ernest Hemingway and Scott Fitzgerald that led their intimate friendship to degenerate into a painfully cruel exercise in sadomasochism? Rivalry played its part in the deterioration of the friendship, particularly as it found expression in Hemingway's comments after Fitzgerald's death and subsequent critical resurrection. But there must have been other powerful forces at work, also. Almost all literary relationships are contaminated to some degree by rivalrous feelings. Few of them end as bitterly as did that of Fitzgerald and Hemingway. Why?

Hemingway had a dark side to his nature, blacker than Zimbabwe granite. When visited by the demon of depression, he could be tremendously cruel and critical of others, much as in the end he visited the final judgment upon himself. From boyhood on Hemingway was fascinated by death, and especially by suicide. His first printed story, in the Oak Park high school literary magazine, ended with a suicide. The subject came up often in his correspondence. He could imagine how a man could be so weighed down by obligations as to take his own life, he wrote Gertrude Stein in 1923. Three years later, when he and Pauline agreed to spend one hundred days apart, he wrote Fitzgerald that he had struggled through “the general bumping-off phase.”

His feelings about suicide changed when his father killed himself in December 1928. Ernest blamed his mother for this tragedy. She had bullied his father into it, he decided. But he could not condone what his father had done. His suicide was an act of weakness, even of cowardice. He addressed the topic directly in the ending of For Whom the Bell Tolls when Robert Jordan, wounded and in pain, rejects the option of taking his own life. Jordan's mind, running in triple time, reminds him of the experience of his father and grandfather, who closely resemble Hemingway's own. His grandfather, like Anson T. Hemingway, distinguished himself in combat during the Civil War. His father, like Clarence Edmunds Hemingway, shot himself with a Smith and Wesson revolver because he could not stand up to his wife. Jordan forgave his father that weakness, but he was also “ashamed of him.” He did not “want to do that business his father did.” So Ernest resisted for a long time the pull of oblivion, even in the extremity of pain. On shipboard following his terrible injuries of the two 1954 plane crashes, he gazed with longing at the restful water flowing by—and did not jump. Finally, he could resist no longer.

The sole attempt at a psychological interpretation of Hemingway was published by psychiatrist Irvin D. Yalom and his wife Marilyn, a literary scholar, in 1971. Admitting the difficulty of arriving at a “dynamic formulation” of a man they never met, the Yaloms used as resources Hemingway's published fiction and letters and the biographical information available at the time, abetted by consultation with General Buck Lanham.

They began, logically enough, with the “powerful imposing figure” Hemingway presented to the world.

Whatever else we can see, always there is virility, strength, courage: he is the soldier searching out the eye of the battle storm; the intrepid hunter and fisherman compelled to pursue the greatest fish and stalk the most dangerous animal from the Gulf Stream to Central Africa; the athlete, swimmer, brawler, boxer; the hard drinker and hard lover who boasted that he had bedded every girl he wanted and some that he had not wanted; the lover of danger, of the bullfight, of flying, of the wartime front Unes; the friend of brave men, heroes, fighters, hunters, and matadors.

This was not only Hemingway's public image, the Yaloms concluded—it was the idealized image he tried to live up to.

The idea of the idealized image they borrowed from Karen Horney, who in her Neurosis and Human Growth (1950) argued that a child deprived of acceptance by his parents or finding in them no realistic model to emulate would instead construct “an idealized image—a way he must become in order to survive and to avoid basic anxiety.” Hemingway's idealized image, according to the Yaloms, “crystallized around a search for mastery.” He became the man who would be master, a goal beyond the reach of any human being. And because his idealized image was unattainable, he was afflicted by recurrent self-doubt and self-contempt and became highly sensitive to any adverse criticism from others.

Living the dangerous existence he demanded of himself, Hemingway was often hurt. He proceeded on the assumption that he could withstand pressures that would fell an ordinary mortal. “[H]e boasted that he had an unusually indestructible body, an extra thickness of skull, and was not subject to the typical biological limitations… being able, for example, to exist on an average of two hours and 32 minutes sleep for 42 straight days.” Similarly, he believed— or made himself believe—that he could work harder and better than others, learn more, drink more, make love more, and so on. Throughout his life, the Yaloms asserted, Hemingway attempted to abolish the necessary discrepancy between his real self and this superhuman idealized self. When he could not do so, he was overcome by anxiety and depression and, in the last years of his life, by paranoia—projecting onto others his hatred for his own real and sometimes unmasterful self.

Where relations with others were concerned, Hemingway carefully kept his distance. In love, he brooked no disapproval and ceded little of himself to his partners. Giving of oneself he saw as a sign of emasculation, and he was determined not to “do that business” of his father, either. Nor would he put himself in a position to be hurt, after his youthful repudiations by Agnes von Kurowsky and his mother. His wives may have loved him—three of them undoubtedly did—but they were not loved back.

In friendship, too, Hemingway withheld commitment. In his edition of Hemingway's selected letters, Carlos Baker called attention to Ernest's highly gregarious nature: a longing “to gather his closest male friends around him for hunting, fishing, drinking, or conversational exploits.” Ernest had a rare capacity for the kind of male camaraderie—the whiskey around the campfire—that could ward off loneliness but required no strong emotional investment. His closest companions, in the last decades of his life, were men he fished or hunted or boxed with. In such company, as Baker put it, he “could relax, boast, show off, gossip and listen to gossip, tell tall tales, make rough jokes, shoot, fish, drink—often competitively—and share what he had and what he knew with those who were close to him in size, strength, or adventurous disposition.” But they were emphatically not close to him in intellectual attainments, and none of them were writers.

Systematically and often with excessive cruelty, he broke off all his literary relationships. Donald Ogden Stewart, who knew Ernest well during the 1920s and was the model for the sympathetic Bill Gorton in The Sun Also Rises, was one of those spurned by Hemingway. In an interview, Stewart tried to puzzle out the reason why. “The minute he began to love you, or the minute he began to have some sort of obligation to you of love or friendship or something, then is when he had to kill you. Then you were too close to something he was protecting. He, one-by-one, knocked off the best friendships he ever had. He did it with Scott; he did it with Dos Passos—with everybody.”

What he was protecting, in the Yaloms' formulation, was his idealized image as a master, a self-created artist beholden to no one and unwilling to be contaminated by any trace of weakness. Fitzgerald was guilty on both counts. He laid Hemingway under obligation during the first years of their friendship, providing Ernest with precisely the sort of professional and personal debt he felt compelled to cast aside. And in many ways—as artist and husband and drinking companion—Fitzgerald demonstrated a vulnerability that Hemingway regarded as contemptible. It may well be that he detected aspects of his own weakness in Fitzgerald's characterological shortcomings and hence responded to them with seemingly undue vitriol. The extremity of Ernest's viciousness toward Scott in A Moveable Feast, Jacqueline Tavernier-Courbin commented, “suggests a projection of [his] own fears of personal and professional failure.”

In the glow of his early success, Fitzgerald wrote in “The Crack-Up,” he held the serene belief that “[l]ife was something you dominated if you were any good.” Then he cracked up and discarded that illusion. Sara Murphy, reading the essay, scolded Fitzgerald for the arrogance of his youthful confidence, but it was Ernest and not Scott who clung to the idea that life could be dominated if you were masterful enough. His son Jack observed that he could not conceive of his father receding into an amiable old age. Given his idealized image of himself, such an accommodation to reality was unthinkable. As Hemingway's health deteriorated and his artistic powers flagged, the man who could not master life chose not to live at all.

If Hemingway needed to think well of himself to survive, Fitzgerald seemed to covet his imperfections. In a document composed when he was fifteen years old, for example, he simultaneously celebrated his superficial attractiveness and condemned his deeper moral failings. Among his positive qualities Fitzgerald listed “superior mentality,” good looks, charm, “a sort of aristocratic egotism,” and an ability to exert a “subtle fascination over women.” On the negative side, he considered himself “rather worse than most boys, due to a latent unscrupulousness.” He was cold, cruel, and “mordantly selfish.” He had a “streak of weakness” in his character, and lacked “the essentials”—a sense of honor, courage, perseverance, and self-respect. His inordinate vanity, he added, “was liable to be toppled over at one blow by an unpleasant remark or a missed tackle.”

Such a harsh self-assessment, unusual from anyone, was astounding from a boy of fifteen. The most interesting things about it were 1) that young Scott Fitzgerald seemed to enjoy chastising himself for his moral shortcomings fully as much as he enjoyed listing his mental and physical virtues, and 2) that his sense of self-worth depended so much upon the opinion of those who watched him avoid thetackle and could devastate him with “an unpleasant remark.” The inner-directed Hemingway drew his strength—and used it up—by trying to conform to the image of himself he carried around inside his head. With so little self-respect, the other-directed Fitzgerald was forever seeking the approval of others, and regarded himself as despicable for making the effort. His compulsion to alienate the very people he wanted to please offered tacit evidence of his failure to value himself. By outrageously demonstating his unworthiness in alcoholic misbehavior, he forestalled others from arriving at a sober reasoned judgment of his inferiority.

Fitzgerald's family background was essential in the formation of his flimsy self-image. No more than Hemingway did he have a father who gave him a paternal image to pattern himself upon. The well-mannered but ineffectual Edward Fitzgerald bequeathed him little beyond fine features, a few courteous gestures, and a fondness for lost causes. But instead of building an unrealizable ideal like Ernest, young Scott took his cue from his mother's ambitions for him. Mollie Fitzgerald spoiled her only son, and pushed him into social worlds beyond his depth. Taking pride in his good looks and charm and “superior mentality,” she encouraged him to show off for the entertainment of others. Scott inherited from her a lasting sense of social insecurity and a demeaning eagerness for the applause of other people. Above all, Fitzgerald wanted to please. In his notebooks he jotted down an Egyptian proverb about the worst things in life:

To be in bed and sleep not,

To want for one who comes not.

To try to please and please not.

Inevitably, he sometimes failed in his efforts to please. “I must be loved,” he told Laura Guthrie in 1935. “I have so many faults that I must be approved of in other ways.” His need to be loved may have been the most serious fault of all.

The continual exercise of his charm, Fitzgerald fully understood, involved him in artifice, and he excoriated himself for this indulgence. In a note written during his Hollywood years, he resolved not to go around “saying I'm fond of people when I mean I'm so damned used to their reactions to my personal charm that I can't do without it. Getting emptier and emptier.” In his fiction, both early and late, he considered the destructive consequences of pleasing others through charm. Amory Blaine, in This Side of Paradise, aspires to become a personage instead of a personality. The difference is that a personage makes his mark through accomplishment and “is never thought of apart from what he's done,” while a personalitydepends on the approval of others for his self-image. Dick Diver, in Tender Is the Night, represents an almost clinical study of a man emptied of vitality by the exercise of an increasingly insincere charm. There is something unwholesome as well as destructive in Diver's overweening need to be loved.

In his campaigns to please, Fitzgerald was far more successful with women than with men. “He liked women,” Zelda said after Scott's death, and they usually “lionized” him. He “kept all the rites,” knew how to flatter and entertain, and was sensitive to shades of meaning in converation. With men, on the other hand, Fitzgerald felt ill at ease and unconfident. He tried too hard, asked too many questions, and often ended by abasing himself.

Unfairly or not, he tended to associate his mother with this failure. In 1931, Fitzgerald became the intimate friend of Margaret Egloff, a psychiatrist then “working with the Jung group” in Switzerland. At her suggestion he wrote out the details of what Egloff called “a Big Dream.”

I am in an upstairs apartment where I live with my mother, old, white haired, clumsy and in mourning, as she is today. On another floor are a group of handsome & rich, young men, whom I seem to have known slightly as a child and now want to know better, but they look at me suspiciously. I talk to one who is agreeable and not at all snobbish, but obviously he does not encourage my acquaintance— whether because he considers me poor, unimportant, ill bred, of of ill renown I don't know, or rather don't think about—only I scent the polite indifference and even understand it. During this time I discover that there is a dance downstairs to which I am not invited. I feel that if they knew better how important I was, I should be invited… I go downstairs again, wander into the doorway of a sort of ballroom, see caterers at work, and then am suddenly shamed by realizing this is the party to which I am not invited. Meeting one of the young men in the hall, I lose all poise and stammer something absurd. I leave the house, but as I leave Mother calls something to me in a too audible voice from an upper story. I don't know whether I am angry with her for clinging to me, or because I am ashamed of her for not being young and chic, or for disgracing my conventional sense by calling out, or because she might guess I'd been hurt and pity me, which would have been unendurable, or all those things. Anyway I call back at her some terse and furious reproach….

The dream patently revealed Fitzgerald's feelings of social inferiority. Iscent the polite indifference and even understand it. According to Egloff, who knew Fitzgerald well, he felt that the rich, powerful, and chic were the people to identify with. “The fact that he was not born into that society galled him, and he hated himself for his own and everyone else's snobbery. He hated his mother for her upward aspirations, and he despised his father for not setting his goal and his career in that direction. But with all his ambivalence his underlying value system was very similar to his mother's.”

One way of winning approval, Fitzgerald discovered in boyhood, was through performing in public. Presented proudly to company by his mother, he recited poems and sang songs. In prep school he cultivated his theatrical bent by writing and acting in plays. At Princeton he wrote for both the Lit and the Tiger humor magazine, but expended most of his efforts on the book and lyrics for Triangle Club shows. Had he not been sent home in junior year, he would almost certainly have become Triangle president in senior year. He had extremely high hopes for the success of The Vegetable, his 1923 comedy—hopes that were encouraged by Edmund Wilson, who had been his collaborator on “The Evil Eye” at Princeton. When his daughter Scottie got involved in the theater at Vassar, he suggested that she might consider starting a career “following the footsteps of Cole Porter and Rodgers and Hart.” He might have “gone along with that gang” himself, he added, had he not been too much a moralist at heart with a desire “to preach at people in some acceptable form rather than to entertain them.” There was a detectable twinge of regret in that November 1939 letter, as if Fitzgerald felt he might have been better off writing musical comedy rather than some of the best stories and novels of the century.

Such a career would have satisfied his lifelong propensity for showing off, often under the influence of alcohol. In marrying Zelda, he found a mate who enjoyed putting on performances as much as he did. During the first years of their marriage, both in an around New York City and in France, the two of them seemed determined to command the attention of their friends through their ostentatious and often shocking misbehavior. They didn't just go to parties or give parties. They were the party.

Biographer James Mellow characterized the Fitzgeralds as “masters of invention… acting out their stories in real life.” The way they acted out was strikingly different. Zelda liked to skirt the edge of the precipice, drawing all eyes to her recklessness, and dragged her husband after her into dangerous pursuits. Scott, on the other hand, was content to attract an audience through demeaning himselfin public. This was his pattern, particularly, when dealing with the very talented and successful. In 1920, upon hearing that Edith Wharton was in Charles Scribner's office, he burst into the room and knelt at her feet in literary homage. In 1928, he threatened to throw himself from the window of a Paris apartment in tribute to the genius of dinner companion James Joyce. When Hemingway was on the scene, Fitzgerald's self-abasement became especially embarrassing. At least twice—at the Murphys' party for Ernest at Juan-les-Pins and at the dinner with Wilson and Hemingway in New York—he actually crawled around on the floor.

In 1931, Fitzgerald took one drink too many at a Sunday party given by Irving Thalberg and Norma Shearer in Hollywood and decided to entertain the assembled actors and directors with his humorous song “Dog.” He was roundly booed for his trouble. Fitzgerald used the incident—somewhat transformed to put his fictional counterpart in a better light—in his excellent story “Crazy Sunday,” just as he wrote other humiliations into Tender Is the Night. These fictional confessions must have been difficult to put down on paper. They are painful even to read about.

According to Arnold Gingrich, Fitzgerald possessed a “strange, almost mystic Celtic tendency to enjoy ill luck as some people enjoy ill health.” Scott, he thought, was as much fascinated by failure as Ernest was enamored of success. “If anything was wrong in his life, and something always seemed to be… then everything was all wrong, and he seemed rather to enjoy saying so.” It was this trait, Max Perkins believed, that drove Scott to write the “Crack-Up” essays and so put his career in jeopardy. He was, in Samuel Johnson's wonderful word, a “seeksorrow” who took pleasure in dramatizing his defeats.

This would seem to qualify Fitzgerald as a thoroughgoing masochist—that is, as someone who “enjoyed” or “took pleasure” in or was made “happy” by his failures and humiliations. But these terms often require redefinition, Shirley Panken asserted in The Joy of Suffering. “What might be meant is need for drama, crisis, sensation, stimulation, or a high tension level, thereby emphasizing one's identity or acquiring a spurious feeling of aliveness.” The need for drama seems to fit Fitzgerald's situation. In a moment of deep intimacy, Rosemary Hoyt says to Dick Diver, “Oh, we're such actors—you and I,” and clearly that is true of the series of performances Diver puts on throughout the novel.

Fitzgerald's personality like Hemingway's was far too complex to be reduced to a simple formulation. Much of his behavior, however, corresponded closely to what Avodah K. Offit classified as the “histrionic personality.” Usually but not always women, such people must be the stars in the series of performances thatmake up their lives. They seek the approval of others through a show of pleasing-ness, and should that fail, through dramatic presentation of their “black vapors.” Often they seduce and discard serial lovers. Though demanding and self-obsessed, histrionics are nonetheless appealing because of their intuitive insights and their “uncanny ability to make sensitive and perceptive observations about others.”

For such people, as often seemed to be true of Fitzgerald, infamy was better than no notice at all. When he did something almost unforgivable—broke the wineglasses, insulted the guests, picked a fight—he followed up with extravagant exhibitions of regret. His first letter to Hemingway took the form of an apology for drunken misbehavior, and throughout their relationship he seemed to find himself invariably in the wrong. With others, too, most notably the Murphys, Scott tried to correct his nighttime indiscretions with morning-after notes and visits. “My God, did I say that? Did I do that?” he would ask. Couldn't they possibly forgive him, considering how bad he felt about what had happened?

When drinking Fitzgerald was apt to become belligerent, as he did on first meeting young Robert Penn (Red) Warren in 1929. After a dinner party in Paris that Zelda skipped, the two writers stopped by the Fitzgeralds' apartment long enough for Warren to overhear a “frightful hissing quarrel” between husband and wife. He and Scott then proceeded to a café where Warren made a flattering remark about Gatsby. “Say that again,” Fitzgerald responded, “and I'll knock your block off.” The next morning Red got a pneumatique from Scott “full of apology, saying he had been under great strain and drunk besides, and asking me to dinner.” Fitzgerald was constantly testing the tolerance of others, as if to see if he could still command their forgiveness. Not everyone reacted as he must have wished. “Between being dangerous when drunk and eating humble pie when sober, I preferred Scott dangerous,” writer Anita Loos commented. And in London, one lady of title simply refused to accept his contrition. He was terribly, despairingly sorry, Fitzgerald wrote her in abject next-day remorse. Oh, was he? she replied.

In a note written around 1931, Scott set down a list of those who responded to his misconduct by snubbing him.

Snubs—Gen. Mannsul, Telulah phone, Hotel O'Connor, Ada Farewell, Toulman party, Barrymore, Talmadge and M. Davies. Emily Davies, Tommy H. meeting and bottle, Frank Ritz and Derby, Univ. Chicago, Vallambrosa and yacht, Condon, Gerald in Paris, Ernest apartment.

Some of the people have disappeared in the mist. But it is possible to reconstruct snubbings by Tallulah Bankhead, Bijou O'Connor, and Ada MacLeish, by Hollywood's John Barrymore, Constance Talmadge, and Marian Davies, by socialites Emily Davies Vanderbilt, Tommy Hitchcock, and Ruth Vallombrosa, and of course by Gerald Murphy and Ernest Hemingway. Fitzgerald would have been particularly sensitive to any slight from three of the men: the war hero and polo player Hitchcock, the elegant and socially impeccable Murphy, and the writer as man of action Hemingway. They were the very three Ernest placed on the roster of those Scott made heroes of. In choosing Hitchcock, Murphy, and himself, Hemingway added, Fitzgerald had certainly “played the field.”

Fitzgerald at his best was a man of great charm and absolute loyalty, generous and supportive. Fitzgerald at his worst was an almost impossible friend, as annoying in his torrents of apology as in the episodes that inspired them. Hemingway found him disturbing in both manifestations, and was as much troubled by the generosity as the groveling.

As a friend, Hemingway treated Fitzgerald with extraordinary cruelty. He used Scott's support and later repudiated it. He insulted Scott in his letters and in his fiction, and after his death conducted a campaign against his reputation. And yet, the feeling between them ran deep.

What Scott loved about Ernest was the idealized version of the sort of man—courageous, stoic, masterful—he could never be. What Ernest loved about Scott was the vulnerability and charm that his invented persona required him to despise. It made for a poignant story, really: one great writer humiliating himself in pursuit of a companionship that another's adamantine hardness of heart would not permit.

Sources

FSF, Notebooks, #1918. Roethke, “Song for the Squeeze Box,” Collected, 111. Prigozy, “Measurement,” 108-109. Mellow, Invented, 244. EH to MP, July 23, 1945, SL, 594. EW, Twenties, 94. Bruccoli, Grandeur, 62. Hobson, Mencken, 389. SD, By Force of Will, 188-189. Sanderson, “Hemingway and Gender History,” Companion, ed. SD, 175-179. Fuentes, Cuba, 415-416. Kennedy, “Gender Trouble,” 196-199. Reynolds, Final Years, 156, 271. Comley and Scholes, Genders, 146. FSF, “Girls Believe in Girls,” Liberty 7 (February 8, 1930), 22-24. SD, “Short History,” 186-167. SD, Fool, 86. FSF, “Wanda Breasted,” Tender Is the Night, ed. Cowley (New York: Scribner's, 1951), 338-345.

Psychological Speculations

Eliot, “Four Quartets,” Complete, 129,144. Waite, Psychopathic, xii-xiv. SD, “Hemingway and Suicide,” 287-295. Yaloms, “Psychiatric View,” 487-494. EH, SL, introd. Baker, xvii-xix. Stewart, “An Interview,” Fitzgerald/Hemingway Annual 1973 (Washington, D.C.: NCR Microcard Editions, 1974), 85. Tavernier-Courbin, Hemingway's Feast, 119. FSF, Crack-Up, 69. Sara Murphy to FSF, April 3, 1936, in Miller, Lost Generation, 161. Reynolds, 1930s, 195. Mizener, Far Side, 20-21. FSF, Notebooks, #23. SD, Fool, 191,192, 59, 13-15, 164-165. FSF to Scottie Fitzgerald, November 4, 1939, 63. Mellow, Invented, xx. Bruccoli, Grandeur, 135, 267, 322. Gingrich, “Coming to Terms,” 58. Panken, Joy in Suffering, 139. Offit, Sexual Self 57-58, 62-64. Mellow, Invented, 353. FSF, Notebooks, #728. EH to Mizener, April 22, 1950, SL, 690.

The End.

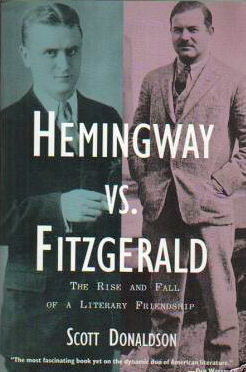

Published as Hemingway Vs. Fitzgerald: The Rise And Fall Of A Literary Friendship by Scott Donaldson (Woodstock, Ny: Overlook P, 1999).