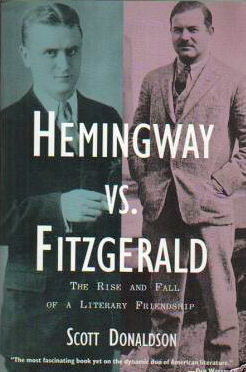

Hemingway vs. Fitzgerald: The Rise and Fall of a Literary Friendship

by Scott Donaldson

Chapter 4

Oceans Apart

Friendship is like money, easier made than kept.

—Samuel Butler

The Fitzgeralds had been back in the States only a short time when United Artists hired Scott to write an original flapper screenplay. The script Scott produced, called Lipstick, was never filmed, but the month that he and Zelda spent in Hollywood had lasting repercussions. Scott became infatuated with the young actress Lois Moran, who was then not quite eighteen to his thirty. Zelda was naturally distressed, especially after her husband explained that he admired Lois because she had done something with her talent through hard work and discipline. In reaction, Zelda burned some of her clothes in a hotel bathtub and threw the platinum wristwatch Scott had given her in 1920 out the window of the train carrying them back east. Once they had settled into Ellerslie, the mansion they had rented on the Delaware River outside Wilmington, she began taking ballet lessons three times a week.

Scott and Ernest had been out of touch during his Hollywood trip, which was as Fitzgerald expressed it the “Goddamndest experience” he'd had for seven years. On his return, however, he resumed his campaign to advance Hemingway's career. During a lunch in Baltimore, he attempted to repair the rift between Hemingway and the influential H.L. Mencken. As editor of the American Mercury, Mencken had dismissed the sketches of in our time as “[t]he sort of brave, bold stuff that all atheistic young newspaper reporters write.” In retaliation, Hemingway dedicated The Torrents of Spring jointly to “H.L. MENCKEN AND S. STANWOOD MENCKEN IN ADMIRATION,” knowing full wellthat S. Stanwood Menken (as his name was spelled) was precisely the kind of self-righteous reformer H.L. Mencken detested. He also gave his character Bill Gorton a sarcastic line about Mencken in The Sun Also Rises. So there were bad feelings between the two, at least on Hemingway's part. Fitzgerald's job was to persuade Mencken, who was “just starting reading” Sun, that his friend Hemingway was a great writer, and to convince Hemingway that Mencken was “thoroughly interested and utterly incapable of malice.” As a first practical step in that direction, he got Mencken to say he would pay $250 for anything of Hemingway's he could use in his magazine. “So there's another market” (in addition to Scribner's), Scott wrote Ernest in March 1927.

“Isn't it fine about Mencken,” Hemingway responded. Fitzgerald's efforts were of limited financial usefulness, as it turned out, for he never published any of his work in the American Mercury. Fitzgerald's next agenting overture was only slightly more beneficial. On March 27 he cabled Hemingway that “VANITY FAIR OFFERS TWO HUNDRED DEFINITELY FOR ARTICLE WHY SPANIARDS ARE SWELL OR THAT IDEA.” Hemingway replied that as a matter of principle he made it a rule not to write anything to order, but in this case Fitzgerald had cooked up a subject he could write about without “jacking off.” In fact, he'd written something the day before, and planned to fix it up and send it along. This piece did not run in Vanity Fair, but may have seen the light of day as “The Real Spaniard,” in the October 1927 issue of a little-known magazine called Boulevardier.

Hemingway's March 31 letter discussing the Spanish article idea was one of the longest and warmest he ever sent to Fitzgerald. While Scott was in Hollywood, Ernest asked Max Perkins for news of him in three separate communications. Obviously, he missed Scott, and after a long silence between them had a great deal of information to pass along.

In the area of literary gossip, Hemingway reported that Harold Loeb (the model for Robert Cohn in The Sun Also Rises) was threatening to shoot him, but had not shown up to do so when Ernest sent word about the times he would be sitting unarmed in front of Lipp's brasserie. Then there was a terrible dinner at writer Louis Bromfield's, where “they had a lot of vin ordinaire and cats kept jumping on the table and running off with what little fish there was and then shitting on the floor.” On the personal front, most of the news was good. He'd seen Bumby in Switzerland, and it was amicably agreed upon that he could see him regularly. Hadley was happy and “very much in love.” Pauline had finally returned from America, and since Ernest had been in love with her for a long time it certainly was “fine to see something of her.”

In addition, Hemingway emphasized his penury, as usual. The Atlantic had taken “Fifty Grand,” but had been “too gentlemanly to mention money.” He himself had been broke for a couple of months, but happily at the moment that “coin-cide[d] with Lent.” He had been living in Gerald Murphy's studio for months, which was “a hell of a lot better than under, say, the bridges.”

At both the beginning and end of his letter, Hemingway emphasized how much the friendship with Fitzgerald meant to him. “And you are my devoted friend too,” Ernest began, taking a cue from the phrase Scott used in signing off his letter about Mencken. No one worked harder or did more for him, and “oh shit I'd get maudlin about how damned swell you are. My god how I'd like to see you.” At the end Hemingway came back to the same theme. The Murphys had been wonderful to him during the trials of the divorce, and so had the MacLeishes. “If you don't mind, though,” he told Fitzgerald, “you are the best damn friend I have. And not just—oh hell—I can't write this but I feel very strongly on the subject.”

Fitzgerald sent Hemingway $100 by return mail. The Atlantic would pay about $200 for “Fifty Grand,” he figured. (Actually, it was $250.) Besides, Scribner's ought to advance him whatever he needed for Men Without Women, the book of short stories scheduled for fall publication. As with The Sun Also Rises, Perkins called on Fitzgerald for advice in connection with this book. The problem had to do with “Up in Michigan,” Hemingway's hard-edged story of seduction that had been cut from In Our Time by Boni and Liveright. Ernest wanted to include it in Men Without Women, but Perkins had reservations. What did Scott think?

“One line at least is pornographic,” Fitzgerald advised Perkins, adding that he did not want his name used in any discussion of the matter with Hemingway. He did not see how the story could be amended. What good was a seduction story with the seduction left out? He suggested that Perkins explain to Hemingway that while such an incident might be overlooked in a book, “a story centering around it points it.” It did not seem to him possible—at the moment, in the United States—that “Up in Michigan” with its physiological details could be published. If that were the case, twenty publishers would be “scrambling for James Joyce tomorrow.”

Before the October 14 publication of Men Without Women, Max Perkins went down to Ellerslie for a weekend with the Fitzgeralds. The grand old house was solid and high and yellow, with columns front and back, second-story verandas, and a lawn running down to the Delaware. But the atmosphere of the mansion had not as Perkins hoped succeeded in transforming the Fitzgeralds' style of life toone of patrician gentility, with Zelda “a stately lady of the manor” and the drinking confined to “port by candle light, accompanied by walnuts.” Instead, Scott was something of a nervous wreck. He needed a month of hard exercise and nothing else, Max thought. He also needed to cut down on smoking and drinking.

Men Without Women, containing half a dozen of Hemingway's finest stories, came out in October. The volume elicited a letter from MacLeish praising its radical reduction of rhetoric: “Ten things 'said' for every word written. Full of sound like a coiled shell. Overtones like the bells at Chartres. All that stuff you can't describe but only do—& only you can do it.” Fitzgerald, too, weighed in with favorable commentary. Without mentioning his correspondence with Perkins on the subject, he told Ernest how glad he was that he had left out “Up in Michigan.” It belonged to “an earlier and almost exhausted vein,” Scott thought. Zelda's favorite story was “Hills Like White Elephants,” his own-leaving aside “The Killers”—was “Now I Lay Me.” He was also enchanted by the opening words of “In Another Country”: “In the fall the war was always there but we did not go to it any more.” Fitzgerald sent Mencken a copy of the book, asking him to “please read” it. Hemingway was “really a great writer, since Anderson's collapse the best we have I think.”

The reviews were less than Ernest might have hoped for. He was particularly upset by Virginia Woolf's “An Essay in Criticism” and F.P.A.'s (Franklin P. Adams's) parody in his newspaper column. Even Perkins found Woolf 's review/essay in the New York Herald-Tribune “enraging,” because 1) it came out a week in advance of the publication date, and 2) Woolf spent so much of her time “talking about the function of criticism instead of functioning as a critic.” Hemingway would have preferred that she not function as a critic at all, for Woolf had little good to say about The Sun Also Rises and even less about Men Without Women. “Common objects like beer bottles and journalists figure largely in the foreground” of Hemingway's novel, she drily observed. As for his stories, she was surprised that work “so competent, so efficient, and so bare of superfluity” did not make “a deeper dent.” The stories were too neatly tied together, too dependent on dialogue, “a little dry and sterile.” Furious, Hemingway wrote Perkins that Woolf belonged to “a group of Bloomsbury people” who lived “for their Literary Reputations” and figured the best way to preserve them was to “slur off or impute [impugn] the honesty of anyone coming up.”

“Thousands will send you this clipping,” Fitzgerald observed as he mailed Hemingway a copy of Adams's parody, based on the tough talk of the hit men in “The Killers.” The piece was well meant, he assured Ernest, who could not havedisagreed more. He was especially annoyed about a comment by Adams about his “swashbuckling affectations of style,” and in a foul mood about the reviews generally. Burton Rascoe in the Bookman had reviewed the book without bothering to read it, he maintained. The reviewer in the New York Times “missed that lovely little wanton Lady Ashley.” Then there was the Woolf. He could count on getting at least two thousand copies of “any review saying the stuff is a pile of shit,” he chided Fitzgerald. It was enough to make him want to quit publishing fiction “for the next 10 or 15 years.”

Another book figured largely in the 1927 correspondence between Fitzgerald and Hemingway. This was Scott's phantom novel, which after one of the longest and most tortuous periods of procrastination in literary history was to emerge in 1934 as Tender Is the Night. Yet by early 1927, Fitzgerald was promising imminent delivery of his manuscript to his editor Perkins, his agent Ober, his friend Hemingway, and probably himself. “Book nearly done,” he assured Ernest in March. Early in June, Scribner's sent him an advance “without a quiver” for the novel he was “now finishing.” In September, Fitzgerald sent Perkins word that he was “hoping… to finish the novel by the middle of November.” Perkins loyally supported Fitzgerald despite the repeated delays. Hemingway took a more cynical stance. In a September 15 letter to Perkins complaining about the meretriciousness of literary prizes generally, he proposed that they cook up a new one. “Couldn't we all chip in and get up say The New World Symphony Prize for 1927-8-9 and give it to, Scott's new novel as an incentive that he finish it?” Writing Fitzgerald the same day, Hemingway noted that he was about to produce “a swell novel” himself and added this caveat: “Will not talk about it on acct. the greater ease of talking about it than writing it and consequent danger of doing same.”

In this letter Hemingway apologized for not thanking Fitzgerald for his $100 loan in April, and promised to pay it back as soon as Men Without Women came out. For the previous five months, he had been living like “the tightest man in the world,” subsisting solely on Scott's $100 and $750 from Perkins, while turning down a $1,000 advance from Hearst magazines on a contract for ten stories—$1,000 apiece for the first five and $1,250 each for the second five.

In acknowledging repayment of the loan, Scott wrote that he hoped Ernest—now married to Pauline—was “comfortably off in [his] own ascetic way” and could not resist telling him that the Saturday Evening Post had upped his price to “32,000 bits per felony,” or $4,000 per story. (This was incorrect: the Post was then paying him $3,500 for stories.) He was “almost through” with his novel, but had to do three stories for the Post to get his head above water. Hemingway hadbeen wise not to tie himself to Hearst's (for one-fourth of Scott's story price), for they had a reputation of feeding on their contracted writers like vultures.

Ernest found Scott's reports on his huge payments as the Saturday Evening Post's “pet exhibit” somewhat annoying. A fragmentary note among Hemingway's papers describes how pleased he was, as a young writer, to receive letters from readers. “Scott Fitzgerald told me,” the piece goes on, that “his price for stories was increased according to the number of letters a story brought in to the magazine that published it. Every five thousand letters it brought in they raised him a thousand dollars. He had three uniformed negroes who answered letters day and night and a white overseer picked out a few of the better letters and read them to Scott as he worked.”

Fitzgerald was either insensitive to the effect such reports had on Hemingway, or, more likely, unable to refrain from what sounded very much like bragging. Charlie Wales in Fitzgerald's “Babylon Revisited” (1931) commits a similar kind of faux pas about money. But there was more than financial information in Scott's letter to Ernest of early December 1927. He also included, for example, a bawdy passage addressing the rumors that were beginning to circulate about Hemingway's rugged masculinity.

Please write me at length about your adventures—I hear you were seen running through Portugal in used B.V.D.s, chewing ground glass and collecting material for a story about Boule players; that you were publicity man for Lindbergh; that you have finished a novel a hundred thousand words long consisting entirely of the word “balls” used in new groupings; that you have been naturalized a Spaniard, dress always in a wine-skin with a “zipper” vent and are engaged in bootlegging Spanish Fly between San Sebastian and Biarritz where your agents sprinkle it on the floor of the Casino. I hope I have been misinformed but, alas! it all has too true a ring…

Hemingway used the same tone in his mid-December reply, supplying a sharper edge to the comic effect by references to drugs, sex, and their children, and by sidelong digs at Fitzgerald's monetary extravagance. “Always glad to hear from a brother pederast,” he began, introducing a new motif. He had “quit the writing game and gone into the pimping game” as more profitable. “Are you keeping little Scotty off the hop any better?” Ernest inquired. He understood that Scott had to keep up appearances, but nobody could convince him that heroin “really does a child of that age any good.” On the bright side, word had reached him about how Scotty “jammed H.L. Mencken with her own little needle the last time he visited at the Mansions.” For his part, Bumby had started making up stories. Hearst's “offered him 182,000 bits for a serial about Lesbians who were wounded in the war and it was so hard to have children that they all took to drink and running all over Europe and Asia, just a wanton crew of wastrels.”

As for himself, he had given up the Spanish Fly game. There was no money in it. But hadn't he got Lindbergh “a nice lot of publicity?” Would Fitzgerald like him to do the same for Scottie or Zelda? Scott was right about the Spanish wineskin outfit he was wearing, but “it had nothing so unhemanish as a zipper.” He had to deny himself little comforts like that, as well as “toilet paper, semi-colons, and soles to my shoes.” If he used any of those, people would “shout that old Hem is just a fairy after all”—again, a theme Fitzgerald had not touched upon.

A missive from Gstaad at Christmastime closed out the 1927 correspondence. Often subject to hypochondria, Hemingway could not have been feeling worse during the holidays in Switzerland. The weather was not cooperating, for it persistently refused to snow. But Ernest probably couldn't have skied anyway, beset as he was by temporary blindness (Bumby had inadvertently stuck a finger in his eye), piles, the flu, and a toothache. “Merry Christmas to all and to all a Happy New Year like this one wasn't,” he commented sourly. But there was a friendly touch for Fitzgerald. “Wish the hell I could see you. Nobody to talk about writing or the literary situation with. Why the hell don't you write yr. novel?” He and Pauline would be coming to the States in March or April, Ernest added. That was precisely when Scott and Zelda were planning to go to Europe.

Hemingway suffered a further physical misfortune early in March when— at two in the morning—he sleepily pulled the wrong cord in the bathroom of his apartment and brought a decrepit skylight crashing down on his head. The blow poleaxed him, and left a deep gash on his forehead above his right eye. Ernest was losing a great deal of blood, and after trying to stanch the bleeding with toilet paper, Pauline telephoned Archie MacLeish for help. MacLeish rushed the giddy Hemingway to the hospital where nine stitches were needed to close the wound, leaving a scar that was noticeable for the rest of his life.

In a curious example of legend-building, journeyman writer Jed Kiley claimed that Hemingway's injury was no accident but instead an attempt at literary assassination by Fitzgerald! This story was circulated in the London Times Literary Supplement (TLS) of July 9, 1964, accompanied by some extremely unlikely dialogue. According to Kiley, he had this conversation with Fitzgerald.

“[Hemingway] is a great writer. If I didn't think so, I wouldn't have tried to kill him that time.”

“Kill him?” [Kiley] said.

“Sure,” Scott said. “I was the champ, and when I read his stuff I knew he had something. So I dropped a heavy glass skylight on his head at a drinking party. But you can't kill the guy. He's not human.”

Upon reading this balderdash, MacLeish wrote the TLS an account of what actually happened, adding that Fitzgerald would have been incapable of talking in such clichés and more importantly, that he had always been Hemingway's generous supporter. Archie neglected to add in rebuttal that Scott was on the other side of the Atlantic when the skylight came down on Ernest's head.

The episode was symptomatic of two uncommon things about Ernest Hemingway: his susceptibility to physical injuries and his knack for getting himself talked about. Not yet thirty, Hemingway had become a famous person, and the wire services spread the news about his accident. From his base at Rapallo Ezra Pound sent Ernest a humorous question: “Haow the hellsufferin tomcats did you git drunk enough to fall upwards through the blithering skylight!!!!!!!” Writers everywhere were noticing his work, and starting to copy his trademark style. As Fitzgerald observed in reviewing the contents of Princeton's Nassau Literary Magazine, the March 1928 issue set a record among American magazines of the year by containing not a single imitation of Ernest Hemingway. “Gosh,” Scott wrote Max Perkins, “hasn't [Ernest] gone over big?”

The reversal of roles between Fitzgerald and Hemingway was well underway by this time. Now it was Perkins and Hemingway in back-channel correspondence about Fitzgerald's troubles, and what might be done to right them. In a March 17, 1928, letter to Perkins, Ernest went out of his way to differentiate himself from Scott's procrastination. Progress on his own novel—which was to appear as A Farewell to Arms the following year—had been delayed, Hemingway admitted. But he had been laid up by his various ills. “[Y]ou see my whole life and head and everything had a hell of a time for a while and you come back slowly (and you must never let anyone know even that you were away or let the pack know you were wounded),” a parenthetical comment underlining his highly competitive nature. He was, he assured Max, working “all the time.” It was nothing at all like Fitzgerald's situation. “[F]or his own good” Scott ought to have had his novel out a year or two years ago. He didn't want Max to think he was falling into that pattern of promising and not delivering, or of “alibi-ing” to himself.

Perkins had a chance to observe Fitzgerald in the flesh on April 6, when he and Scott had a long talk on the roof of the Plaza Hotel overlooking Central Park. Scott “has made no progress with his novel for a long time,” Max reported, because of “always having to stop to write stories.” Worse yet, he was obviously depressed. His nervous attacks—Fitzgerald called them the “Stoppies”—had ended, but the drinking had not. The night before Perkins saw him, in fact, Scott had been partying with Ring Lardner. All of this news Max passed on to Ernest, but neither of them knew about the degrading incident Scott memorialized in his Ledger as “Black Eyes in the Jungle.” The Jungle was the Jungle Club, a speakeasy in New York. The black eyes were administered by a speakeasy bouncer when an obviously intoxicated Fitzgerald refused to leave without another drink. There would be other incidents like that in the months to follow.

When Perkins's letter about Scott reached Hemingway, he and Pauline were in Key West, checking out the environs as a possible future home site. It was a satisfyingly unliterary place. Nobody believed Ernest when he said he was a writer and “[t]hey haven't even heard of Scott.” So Ernest wrote Max on April 21, the same date the Fitzgeralds sailed for Europe, interposing an ocean between them yet again. He offered to cable Scott's ship with a message of support and reassurance. As he saw it, Hemingway told Perkins, Scott was stalled by unrealistically high expectations. After Gilbert Seldes and others said such fine things about The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald figured his next book had to be “a GREAT novel.” This scared him, and so he built up “all sorts of defences like the need for making money with stories etc. all to avoid facing the thing through.” Scott was really as prolific as a guinea hen but had “been bamboozled by the critics” into thinking he laid eggs like the ostrich or the elephant. Ernest's own novel was proceeding apace, and during the afternoons he was having a fine time “catching tarpon, barracuda, jack, red snappers, etc.” in the waters of the Gulf Stream.

Perkins's next letter to Hemingway sounded more optimistic about Fitzgerald, who had called him in good spirits the day before he sailed. Without responding to Ernest's theory about critical overpraise, Max proposed that Scott's worst problems resulted from mismanaging money. “It is true,” he wrote, “that Zelda, while very good for him in some ways, is incredibly extravagant.” They ran their house in Delaware carelessly, and the servants were robbing them. If only they didn't throw money away, Scott could easily be in a position of independence.

In Paris, the Fitzgeralds settled into a Paris apartment on the rue Vaugirard for six months. Zelda became increasingly abosrbed in the ballet, taking lessons from the distinguished Madame Lubov Egorova, formerly of the Diaghilevtroupe. Scott hoped that fresh European surroundings could spur him on to artistic achievement, as they had in the case of Gatsby. He wrote Perkins around July 21 that the novel “goes fine” and that those he'd read portions of it to “have been quite excited.” He was encouraged when James Joyce announced at a dinner party that he expected to finish his novel “in three or four years more at the latest.” And Joyce worked “11 hrs a day to [Scott's] intermittent 8.” His own novel, Fitzgerald promised, would be finished “sure in September.” Perkins passed on the good news to Hemingway.

It was not true. The change in location did no good. Fitzgerald was not working eight hours a day, or anything like it. And his marriage was coming apart. “You were constantly drunk,” Zelda later wrote in accusation. “You didn't work and you were dragged home at night by taxi-drivers when you came home at all. You said it was my fault for dancing all day. What was I to do?” Scott's recollection was that in her passion for the ballet Zelda had retreated into herself just as he had four years earlier, when he was writing The Great Gatsby and “living in the book.” She was indifferent to him and to Scottie, and paid no attention to the bad apartment or the bad servants. She refused to accompany him to Montmartre nightclubs, and—infuriatingly—did not even seem to mind when he brought home intoxicated undergraduates for meals. He began to go to the Closerie des Lilas alone, where he could recall the happy times he'd had there with Ernest and Hadley, Dorothy Parker and Robert Benchley. He also went to jail twice during that Parisian summer of “[d]rinking and general unpleasantness.” Worst of all, “[t]he novel was like a dream, daily farther and farther away.”

At midsummer Fitzgerald essayed another of his wisecracking letters to Hemingway. This time, he said, word had reached him that “Precious Papa, Bullfighter, Gourmand” had been seen bicycling through Kansas, “chewing & spitting a mixture of goat's meat & chicory which the natives collect & sell for artery-softener and market-glut.” Rumor had it that Ernest was to “fight Jim Tully [a hobo writer] in Washdog Wisconsin on Decoration Day in a chastity belt with [his] hair cut a la garçonne.” As a fallen-away Catholic Fitzgerald scoffed at Hemingway's conversion that enabled him to marry Pauline Pfeiffer in the church: “Well, old Mackerel Snatcher, wolf a Wafer & a Beaker of blood for me.” But he still had Hemingway's career in mind, imploring him to send a story to George Horace Lorimer, editor of the Saturday Evening Post, and acknowledging that he had read “Mencken's public apology”—a reference, apparently, to Mencken's largely favorable notice of Men Without Women in the American Mercury. In closing, Scott urged Ernest to “[p]lease come back” to Paris while he was still there.

Hemingway did not get around to answering this letter until early October. He had been busy finishing the first draft of A Farewell to Arms—“God I worked hard on that book”—and took the news of Fitzgerald's working eight hours a day with a healthy dose of salt. “Well Fitz you certainly are a worker. I have never been able to write longer than two hours myself… any longer than that and the stuff begins to become tripe but here is old Fitz whom I once knew working eight hours every day.” What was his secret? Ernest wondered. He looked forward “with some eagerness to seeing the product.”

Hemingway had also become a father for the second time, this time to a baby boy named Patrick who was built like a brick shithouse, laughed all the time, and slept through the night. He was thinking of hiring out his services as a progenitor of perfect children. Taking up the issue of his new-found faith, Ernest commented that as a prospective father “Mr. Hemingway has enjoyed success under all religions. Even with no religion at all Mr. Hemingway has not been found wanting.” Where would Scott be located the end of October? “How's to get stewed together Fitz? How about a little mixed vomiting or should it be a 'stag' party.”

Meanwhile Perkins and Hemingway had been continuing their periodic discussion of Fitzgerald. He'd heard a number of rumors about Scott, and wished “to Heaven he'd turn up,” Max wrote Ernest September 17. Ernest replied with word that his old newspaper friend Guy Hickok had seen Fitzgerald in Paris “very white and equally sober.” Ernest was “awfully anxious to see him,” too, though not at all sure that Scott would be better off in the States than overseas. He'd written Gatsby in Europe, after all, and drank no more there than anywhere else. On October 2, Perkins announced that Fitzgerald had sailed for the States three days before. Max would let Ernest know “how Scott seems” as soon as he could. “Perhaps the news will be really good.”

Perkins was still worried about the Fitzgeralds' extravagance, however, and for a solution he looked to Zelda. “[She] is so able and intelligent,” he wrote Hemingway, “and isn't she also quite a strong person? that I'm surprised she doesn't face the situation better, and show some sense about spending money.” Ernest was anything but surprised. Instead of regarding her as a possible good influence, he wrote Max on October 11, he held Zelda responsible for “90% of all the trouble” Scott had. Almost every bloody fool thing he had done was “directly or indirectly Zelda inspired.” He thought Scott might have become “the best writer we've ever had or likely to have if he hadn't been married to some one that would make him waste Everything.” Instead of writing the novels he had in him, Scott was pooping away his talent on Saturday Evening Post stories.Ernest didn't blame Lorimer, he blamed Zelda, though he wouldn't for a moment want Scott to believe he thought so.

The following month, Hemingway and Fitzgerald finally saw each other again, after a two-year absence.

“Une Soirée Chez Monsieur Fitz…”

…was the title Hemingway assigned to the tale of his November 17-18 weekend visit to “Ellerslie Mansion on the Delaware River—the ride from the… game— the French chauffeur and the rest of it.” In an undated note among his papers, Ernest listed this Fitzgerald encounter as one among half a dozen “Stories to Write.” While he was working on A Moveable Feast in the late 1950s, he managed to get the beginnings of the story down on paper.

This particular Fitzgerald-Hemingway reunion commenced on the morning of the Princeton-Yale game. Ernest and Pauline came to the campus from New York, accompanied by Henry (Mike) Strater, an artist who had been a friend of Fitzgerald's as a Princeton undergraduate and who later, in Paris, painted two excellent portraits of Hemingway. Scott and Zelda were already at Princeton, staying at the Cottage Club. The five of them were to go to the game at Palmer stadium, and then travel to Ellerslie for the evening festivities.

First, though, Scott and Ernest staged a morning mini-celebration of their own. By the time they arrived at the Godolphins'—Isabel, a childhood friend of Ernest's from Oak Park, had married Princeton professor Francis Godolphin—both were “a bit tight and very cheerful.” The two companions struck Francis as “very harmonious, enjoying each other and having a hell of a fine time.” Then they left for Cottage Club and the game, which Princeton won, 12-2. The result contributed to Fitzgerald's high spirits, but he maintained a reasonable level of sobriety during the game. The trouble, according to Hemingway's four-page typescript, began on the post-game train ride from Princeton Junction to Philadelphia.

Wandering the aisles of the train, Scott began asking indiscreet questions of absolute strangers. Several women were annoyed by him, but Ernest and Mike spoke to their escorts in order to “quiet any rising feeling” and maneuver Fitzgerald out of trouble. Spying a lone traveler reading a medical book, Scott took the book from him in courtly fashion, returned it with a low bow, and announced loudly, “Ernest, I have found a clap doctor!” When the insult wasgreeted by silence, Fitzgerald repeated it. “You are a clap doctor, aren't you?” he asked the man. And again, “A clap doctor. Physician, heal thyself.” The poor medical student wanted no trouble, and so the Fitzgerald-Hemingway-Strater party got to Philadelphia “with no one having hit Scott.”

There to meet them at the station was Philippe, a Parisian taxi driver and former boxer Scott had brought back with him from Paris as combination chauffeur, butler, and drinking companion. Philippe drove them the rest of the way in the Fitzgeralds' Buick. It was “a nightmare ride,” for the Buick kept overheating and Scott would not let Philippe stop for oil or water. American cars didn't need oil, he insisted, only worthless French cars did. There was no arguing with him on this point, Philippe told Ernest, and Zelda was even more adamant. As they neared Ellersie, Scott and Zelda quarreled about where to turn off the main road. Zelda thought the turnoff was much further on and Scott insisted they had already passed it. Philippe eventually found the right road when both Fitzgeralds were napping, and the Buick limped home safely. The next morning when he drove Scottie to church, Philippe confided to Hemingway, he would take the car to a garage for service.

Hemingway's written recollection breaks off here, but from conversation and letters it is possible to summon up much of what happened next. Scott was obviously trying to impress Ernest with his surroundings and style of life. Ellerslie itself, with its rolling lawns and big trees, contributed to the effect. So did the six bottles of fine Burgundy Fitzgerald uncorked at dinner. But the false front fell away with the liquor and Fitzgerald's penchant for humiliation. If what Hemingway told A.E. Hotchner was accurate—and many things he told Hotchner were not—Scott began insulting the attractive black maid who was serving dinner. “Aren't you the best piece of tail I ever had?” he repeatedly asked her. “Tell Mr. Hemingway.”

A minor crisis developed the next morning. Playing lord of the manor, Scott showed up in blazer and white flannels and demanded that the guests play croquet on his handsome lawns. Ernest, who took no interest in “forced games” and remembered Scott's missing the train from Paris to Lyon, became extremely anxious about getting to the station to catch the one Sunday train to Chicago. He need not have worried so much, judging from the bread-and-butter note he sent Scott the next day. “We had a wonderful time—you were both grand—I am sorry I made shall I say a nuisance of myself about getting to the train on time—We were there far too early.” Ernest's letter went on to refer to some unexplained trouble with the police at the station, but that too, apparently, was not of much moment. “It was great to have you both here,” Scott wrote back, “even when Iwas intermittently unconscious.” Mike Strater refused to participate in such polite smoothing away of the weekend's rough spots. Three days later, he was only beginning to recover from the hangover. “A bullfight is sedative in comparison,” he wrote Ernest. “…And [Scott] is such a nice guy when sober.” The worst of it, Mike privately thought, came from the combustible chemistry between Scott and Ernest. “Those two… brought out the worst in each other.”

Three weeks later, Ernest was riding another train with his son Bumby, en route from New York to Key West, when a telegram reached him with the news that his father had died. Caught short of cash in the emergency, Hemingway wired Perkins and as a backup telephoned Fitzgerald, who immediately responded by telegraphing $100 to the North Philadelphia station. Ernest left Bumby in the care of a Pullman porter for the rest of the trip to Key West and took the overnight special to Chicago.

“You were damned good and also bloody effective to get me that money,” Ernest wrote Scott from Oak Park a few days later. The death, as he must have feared, was a suicide. “My Father shot himself as I suppose you may have read in the papers.” The blow hit him hard, the more so because—as he wrote Perkins a week later—“my father is the one I cared about.” His mother had thought him irresponsible, and Ernest was out to prove her wrong. He “handle[d] things” at the funeral, he told Max, and realized further that he had to buckle down and finish his book so that he could help out the family (the two youngest children were still in high school). There wasn't much money. His father had cashed in his insurance and invested the funds in Florida real estate, just as the land boom turned to bust.

As good as his word, Hemingway plunged ahead with A Farewell to Arms when he got down to Key West. The novel was finished by late January, but Hemingway told Perkins he couldn't have the book unless he came down to get it and went fishing with Ernest and his friend, the artist Waldo Peirce. Why don't you come along? Max proposed to Scott. Perkins was not at all persuaded by the Hemingway-Peirce theory that the sharks were more afraid of him than he was of them, and would feel safer with Scott on board. It was the first of several invitations for Fitzgerald to join Hemingway in male camaraderie and the pursuit of large creatures of the deep. Scott accepted none of them. He was no more an out-doorsman than Ernest was a croquet player.

Sources

Bruccoli, Grandeur, 257-260. FSF to EH, March 14, 1927, PUL. Bruccoli, Scott and Ernest, 56-58. FSF to EH, March 1927, Letters, 299. EH to FSF, March 31, 1927, SL, 248-250.. FSF to EH, telegram, March 27, 1927, PUL. FSF to EH, April 18, 1927, Life in Letters, 149. MP to FSF, May 10, 1927, and FSF to MP, ca. May 12, 1927, Scott/Max, 146-147. MP to EH, April 13, 1927 and October 14, 1927, Only Thing, 61, 66-67. MacLeish to EH, ca. November 1927, Letters of Archibald MacLeish, ed. R.H. Winnick (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983), 199. FSF to EH, November 1927, Letters, 300-301. FSF to Mencken, inscribed in Men Without Women, ca. October 1927, Life in Letters, 210. Woolf, “An Essay in Criticism,” New York Herald Tribune Books, October 9,1927), 1, 8.. SD, “Woolf vs. Hemingway,” 340-342. F.P.A., “The Importance of Being Ernest,” “The Conning Tower,” JFK. EH to FSF, ca. November 1927, PUL. MP to EH, June 8, 1927, Only Thing, 62. FSF to MP, September 1927, Life in Letters, 207. EH to MP, September 15, 1927, Only Thing, 64. EH to FSF, September 15, 1927, SL, 260-262. FSF to EH, December 1927, Letters, 302-303. FSF, “Babylon Revisited,” Short Stories, 618-619. EH to FSF, ca. December 15, 1927, SL, 267-268. EH to FSF, ca. December 25, 1927, PUL. Baker, Life Story, 189-190. “The Bruiser and the Poet,” Times Literary Supplement, July 9,1964,613, and September 3,1964, 803. Alan Margolies, “‘Particular Rhythms’ and Other Influences: Hemingway and Tender Is the Night,” Hemingway in Italy, ed. Lewis, 69. FSF to MP, after January 24,1928, Correspondence, 213. EH to MP, March 17, 1928, SL, 273-274. MP to EH, April 10, 1928, Only Thing, 70. Mellow, Invented, 315-316.EH to MP, April 21, 1928, SL, 276-277. MP to EH, April 27, 1928, Only Thing, 73. FSF to MP, ca. July 21, 1928, Scott/Max, 152. ZF to FSF, late summer/early fall 1930, Correspondence, 248. FSF to ZF, late summer (?) 1930, Correspondence, 240-241. FSF to EH, ca. July 1928, Correspondence, 220-221. EH to FSF, ca. October 9, 1928, SL, 287-289. MP to EH, September 17, 1928, Only Thing, 77. EH to MP, September 28, 1928, SL, 285. MP to EH, October 2, 1928, Only Thing, 81. EH to MP, October 11, 1928, SL, 289-290.

“Une Soirée Chez Monsieur Fitz…”

EH, Item 720b, JFK. Meyers, Fitzgerald, 181. EH, Item 183, JFK. Mellow, Hemingway, 365-366. Reynolds, Homecoming, 204, 208-209. Mellow, Invented, 328. EH to FSF, ca. December 9,1928, SL, 291. EH to MP, December 16,1928, Only Thing, 83-84. EH to MP, January 8, 1929, SL, 292. MP to FSF, January 23, 1929, Correspondence, 223.

Next Chapter 5 1929: Breaking The Bonds

Published as Hemingway Vs. Fitzgerald: The Rise And Fall Of A Literary Friendship by Scott Donaldson (Woodstock, Ny: Overlook P, 1999).