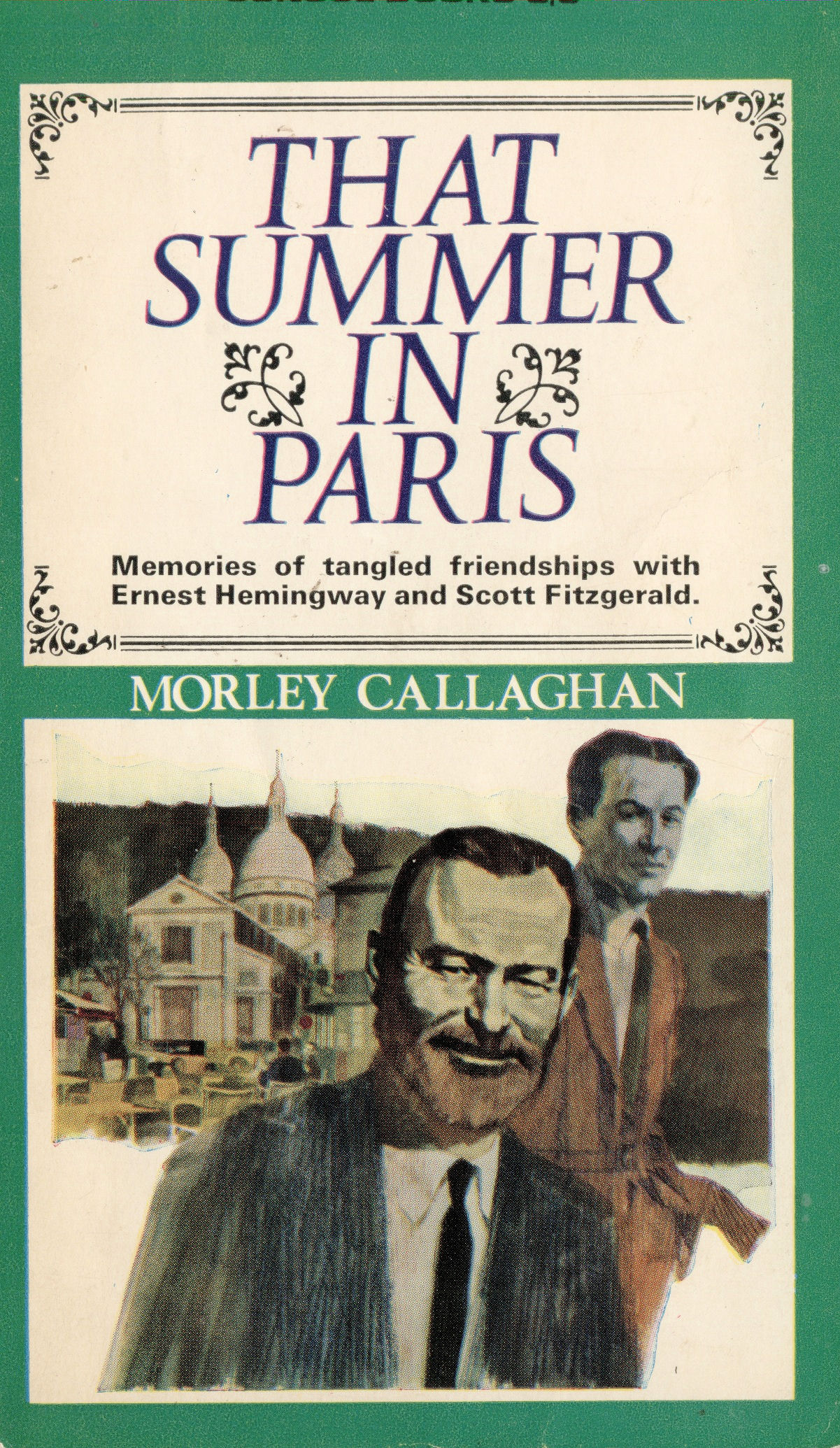

That Summer in Paris: Memories of Tangled Friendships with Ernest Hemingway and Scott Fitzgerald

by Morley Callaghan

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

LOOK at it this way. Scott didn’t like McAlmon. McAlmon no longer liked Hemingway. Hemingway had turned against Scott. I had turned up my nose at Ford. Hemingway liked Joyce. Joyce liked McAlmon. Yet these men, often so full of ill will for each other, nursing the little wounds to their vanities, could retire to the solitude of their own rooms and work long hours—sometimes ten hours—a day at the work they loved which gave them their real dignity. Hemingway had an expression I could never quite get used to. He would say of someone, “He doesn’t know how to behave.” The social criticism, the ethical position behind this simple statement, in fact all the implications behind it, used to mystify me. However, McAlmon certainly was one of those who “didn’t know how to behave.” Yet he too could suffer and struggle to protest himself against too painful an indignity.

Around the Quarter, indignities, bitter or comical, were shared so frequently they became little more than part of the daily gossip. With Scott at the Deux Magots I had shared a painful indignity. A few nights later with McAlmon, I shared one that was absurd.

After nine, when we were in our chairs at the Select, McAlmon came along the street looking for us. It wasn’t McAlmon’s style to come openly looking for anyone? He would rather have it appear that he had just happened to encounter you. And tonight we could see he was serious and preoccupied. When an hour had passed, he looked at his watch. “Let’s go and sit in the Falstaff,” he said casually. We demurred. More unlike himself than ever, he coaxed us. “No, you go ahead and we’ll join you later,” I said. But he wouldn’t have it that way. We were his good friends. Who else was there to sit with? Just because he had told an acquaintance he would be in the Falstaff at ten, we wouldn’t abandon him, would we? So we went with him to the Falstaff and sat at a corner table. As he talked his eyes would shift around the room. I thought he was looking for his friend. In a little while a big six-foot Swede came in with a little guy. They sat at the bar. After they had ordered drinks from Jimmy, they turned and stared at McAlmon. “There he is,” McAlmon whispered. His manner had changed. His aloof expression, his indifferent tone, his whole manner of lordly disdain had gone. “Why doesn’t he join us?” I asked.

“His name is Jorgenson,” McAlmon went on whispering. “I had some trouble with him last night in the Dingo. He said he’d be in here at ten tonight to beat me up—if I came.”

McAlmon’s weak smile, as his eyes met mine, was half apologetic. A little chill touched my neck. Suddenly I was nervous. As my wife’s eyes met mine I could see that she, too, knew what was expected of me. McAlmon might have been an inch taller than me, but he was light and thin, and no battler, and if big Jorgenson came over to the table and started slapping him around, I was supposed to defend him. I had been brought along as his bodyguard. It was news to me that McAlmon was aware of my boxing dates with Hemingway. On only one occasion, the one I have mentioned, had I talked about boxing. But our part of the Quarter was like a little village. Evidently hundreds of eyes had watched Ernest and me coming along the street, Ernest carrying the bag. Yet it was possible even that Jimmy, the bartender, had talked, which may have been why McAlmon had suggested to Jorgenson they meet in the Falstaff.

In a sense, McAlmon had been my first patron. He had been the one who had peddled my stories around. Outrageous as he was, I did like him. No matter what McAlmon did, or how angry I got at him, I liked him. And if Jorgenson should come over and punch him on the nose, what choice did I have? But I was not a man who liked testing his courage. I hated it. Whenever some occasion arose that was to be a test of my courage I became gloomy and very quiet, and if, out of deference to my pride, I knew I would have to go through with it, I became almost inert. I did whisper bitterly, “I suppose I’m to look after the big guy.” When McAlmon didn’t answer, I knew how he“was suffering from the indignity of his position, so I added, “If they come over here you keep your eye on the little guy, eh?”

The tables weren’t crowded. There would be some room to move around if I could get from behind the table, I told myself. I had to have room to move around. Nervous and gloomy though I was, I prepared the campaign. Then I saw that big Jorgenson at the bar was talking to Jimmy. And I seemed to hear the conversation, or rather what I hoped might be the conversation, as Jorgenson looked over at our table and turned to Jimmy. Jorgenson would be saying,“Who’s the guy sitting with McAlmon?” and I prayed that Jimmy would say, “Him! He always comes in here with Hemingway after they’ve been boxing. And Hemingway always has a cut mouth.” Why shouldn’t Jimmy say this to Jorgenson? Hey, Jimmy, look over at me. I’ll smile and wave to you, I thought.

I don’t know what Jimmy talked about, but big Jorgenson, listening, would look over at our table and try to grin derisively. Watching him, I met his eyes with what I hoped was cold aristocratic disdain. Jorgenson and his friend went on whispering. Laughing and joking, they would both turn and stare at McAlmon. Ah, but the great thing was they didn’t get off their stools. At our table there had been no further conversation at all. Finally Jorgenson and his little friend, both with a weary, bored , yet self-conscious air, said good night to Jimmy. They left without a single belligerent glance in our direction.

I sighed with relief. McAlmon, too, enjoyed a quiet relaxing moment. Then he became himself again. The old knowing, superior and contented little grin came on his face. It struck me that he was consoling himself in his humiliating position with the knowledge that he had known what would happen, had planned it beautifully, had out-thought, out-manoeuvered big Jorgenson. Anyway, there he was, safe and sound and lordly again, rejoicing in the absurdity of the situation. We had a drink. It’s too bad big Jorgenson wasn’t famous. He was a mystery story writer, I believe. If he had been famous, McAlmon could have told the story, told how he had outwitted him and made him behave like a puppet, and with the story dragged him down. A good story, one that got close attention and was eagerly repeated, was one that made a distinguished friend look ridiculous.

We all gossiped, I suppose, and malice is more to be enjoyed than the celebration of virtue. McAlmon would even take a crack at his friend Joyce. “One good thing about you is you’re not influenced by Joyce,” he said to me. “Let Joyce have his Irish tenor prose.” A man had to stand up under this general belittlement. The good ones did. It could be said that Ernest, taking the attitude he did to Scott, was belittling him. Of course he was. But Scott stood up under it. I mean as a person he stood up. I never heard him make a single derogatory remark about Ernest. There is a story that he had some kind of envy of Ernest’s great writing skill. It can’t be true. My two friends may not have been seeing each other, and one, Scott, might be feeling hurt and rejected, but the personal loyalty he seemed so desperately bent on offering to Ernest used to embarrass me.

Next Chapter 25

Published as That Summer In Paris: Memories of Tangled Friendships with Ernest Hemingway and Scott Fitzgerald by Morley Callaghan (New York: Coward-Mccann, 1963).