Who Can Fall In Love After Thirty?

by Zelda Fitzgerald

As maturity forces order and segregation upon human lives love falls naturally into place as a habit, or it doesn’t exist at all.

A person who ever since the age of twenty has been wooing sleep through a succession of half-remembered but significant faces, might conceivably do some of his most powerful loving after thirty, but for those less romantic—no. If there is an hour or two in the course of the day which has been habitually passed since the impressionable years in nebulous and undeliberate speculation upon the romantic, the chances are that the victim of this attitude, upon being presented with a member of the opposite sex possessed of necessary vibration, will succumb whether he be twenty-four or going on eighty-seven.

On the other hand, a man who has never fitted himself into any moving picture save the films of Tom Mix, or whose waking dreams have always been of empire, is likely to approach the mating impulse with self-control and suspicion, because it is not identified in his mind with those roseate eventualities which we promise ourselves as rewards. He soon finds that the face of his lady, no matter how enamored he is, and his plans and schedules are not intermingled. The lady is something extra which is not the reality of his life. The lady loses.

But where the habit of being in love is of long enough standing to leave a vacancy when love itself has gone the way of all flesh, the patient notoriously becomes susceptible to a grand passion, as has been the case of so many real and fictitious men on the rebound, neglected husbands or wives, ex-consorts of Nat Goodwin and any maharaja seeing Paris for the first time.

All the “it” in all the works of Elinor Glyn has not been responsible for one-fifth of the undying passions inspired by the fact that boys of twenty and girls of eighteen have little to brood about except each other and can, with admirable dexterity, fit any name into a popular song, any photograph into their favorite frame.

People who realize young that emotions are measured by their depth and not by how long they last are not likely to abandon the excitement and promise that lies in emotional flights when they reach an age which can afford indiscretion, because sentimental affairs are progressive and the habitual lover approaches each succeeding one believing himself endowed by past experience with the clarity, wisdom, and poetry requisite to make this last the love of his life. At ninety he is probably still feeling a vague sense of frustration that his own willingness has met with no adequate entanglement, and contemplating a companionate marriage with his trained nurse. Passion is no less real for the fact that it is repetition. In fact, as years and events press in and fill life with an accumulation of tastes, and a knowledge of how to indulge them, an amorous attachment seems to prove its virility by its mere recognition.

That life is ordinarily so highly organized by the time one is thirty that the intrusion of any unexpected force is more easily controlled and disciplined does not mean that the force is less profound. Younger people in love usually have not got away from the sense of being taken care of, and feel more necessity for human and binding contact. By the time a man has blundered confusedly into the age of responsibilities, he has realized that the qualities he sought in people he found most satisfactorily understandable in himself, that his most vital contacts lay in a community of working interests, that the mystery he thought lay in people was in reality his own wonder and bewilderment—and so if he has passed the thirty mark without a walk down a beribboned aisle, he is not likely to tread it impetuously later. Men are by then familiar with the sacred smell of greenish lilies and wary of the fashionable suckings of organ pipes.

But they remain capable if not voluntary candidates for falling, first, aesthetically in love and, second, curiously in love (which is different from the mystery quality of young emotion), or third, possessively in love, when they feel they have met a paragon with whom it is flattering to be seen, and fourth, advisedly in love for quite worldly reasons.

The one passion that does not exist for the men of forty is the bombastic, reckless, uncalculated, uncompromising one mostly responsible for adolescent marriages. Their horizon has broadened, their energies are spread over a wider field, they have learned to discipline and weigh their impulses toward adventure. The whole varied glamour of existence can no longer be concentrated at will into another person, but that does not mean the urge toward the one of their choosing is less sincere. The measure of a man’s tenderness cannot be taken by how violently he yields to it because he will yield according to his necessity to annex the object of his passion—and a full life naturally feels that necessity less.

Nevertheless it is the loves over thirty that have, as proof of their vitality, led to operas and Anna Karenina and the recent recipes in the Daily News for cooking Ruth Snyder.

Perhaps the often public character of adult philanderings leads to a belief that they are abnormalities, but it is they are too recurrent to be the exceptions to the rule. The fact that mature emotional response soon reduces itself to essentials does not mean that it is of a different quality from youthful enthusiasm in a like direction—it simply means that the means of expression are different. One’s vocabulary changes much more than what one has to say. Perhaps the loyalty to the lyricism of some young forgotten love affair may help keep some men free, or the natural skepticism which accumulates with the years, or lack of money.

But while one of these may suffice to make the church door look the black hole of Calcutta to a man of the “about town” age, not all of them together could stop his redecorating his apartment, or changing his haircut, or making any of those personal adjustments that he bravely thinks he makes to please himself when he comes in contact with a girl who suggests to him the things he likes: the top of the Alps or the Ritz Bar or Mother’s pancakes or achievement.

It seems to us that at thirty, the haze of youth having lifted a little, emotions are stronger for their clarity, more definite for the fact that by then they have a category, a place where they belong—for the same reasons that wine in a bottle with a year is better than wine on tap; and if it is more costly and intoxicating, well, maybe that’s why people drink less of it!

Notes

1. Nat Goodwin (1857-1919), comedian and actor.

2. Elinor Glyn (1864-1943), English novelist, author of Three Weeks (1907), who was responsible for defining “it” as sex appeal.

3. Ruth Snyder and her lover, Judd Gray, were executed in New York for the 1927 murder of her husband.

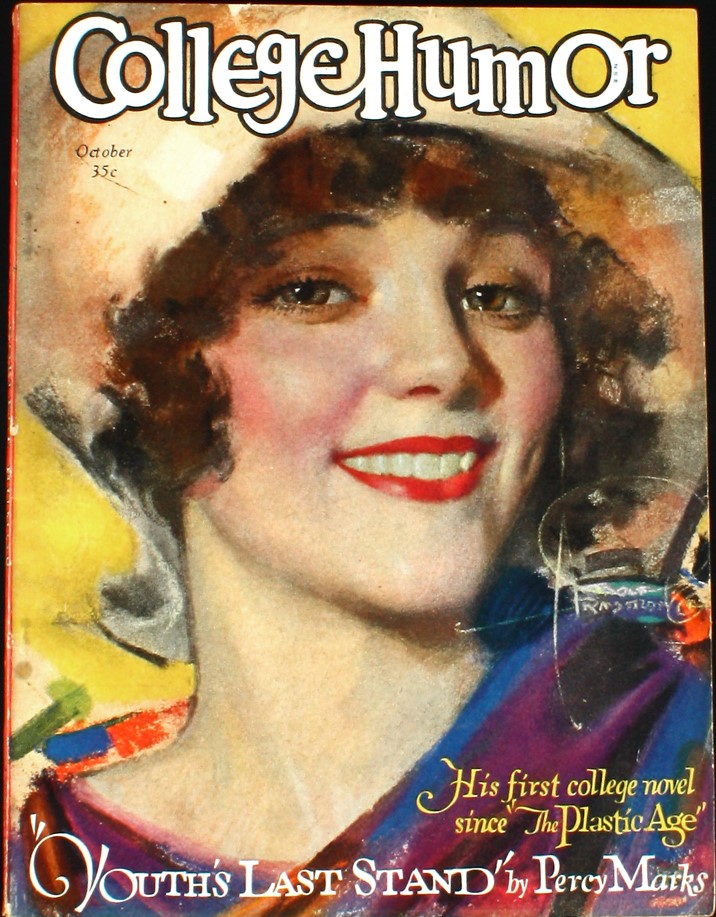

Published in College Humor magazine (October 1928), published as by F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald.