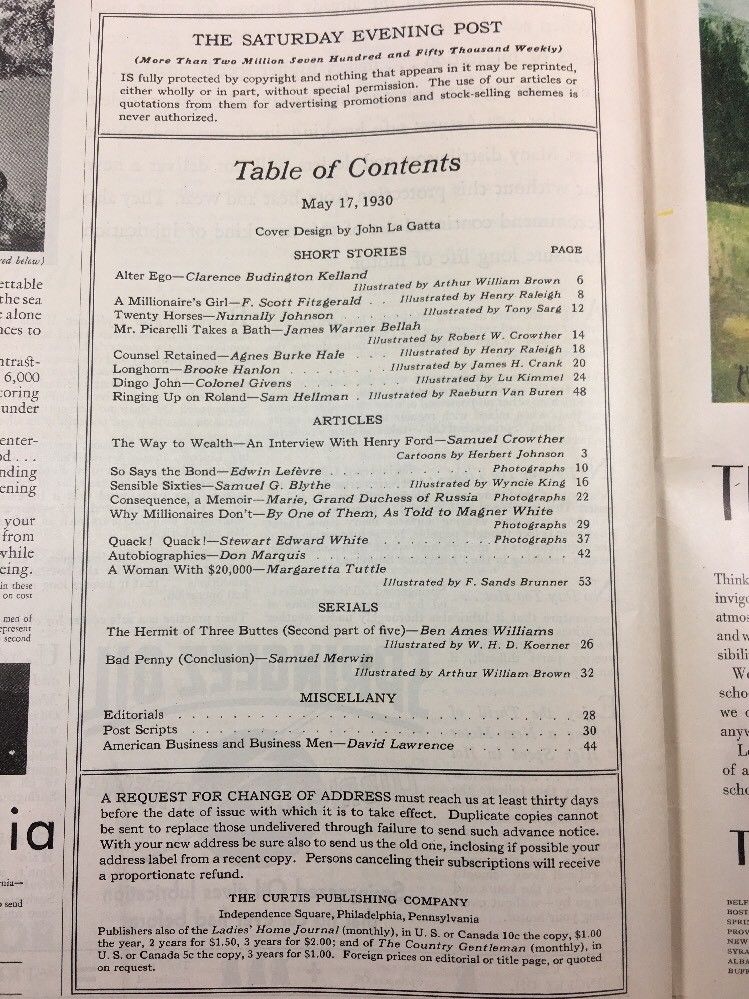

A Millionaire’s Girl

by Zelda Fitzgerald

Twilights were wonderful just after the war. They hung above New York like indigo wash, forming themselves from asphalt dust and sooty shadows under the cornices and limp gusts of air exhaled from closing windows, to hang above the streets with all the mystery of white fog rising off a swamp. The faraway lights from buildings high in the sky burned hazily through the blue, like golden objects lost in deep grass, and the noise of hurrying streets took on that hushed quality of many footfalls in a huge stone square. Through the gloom people went to tea. On all the corners around the Plaza Hotel, girls in short squirrel coats and long flowing skirts and hats like babies’ velvet bathtubs waited for the changing traffic to be suctioned up by the revolving doors of the fashionable grill. Under the scalloped portico of the Ritz, girls in short ermine coats and fluffy, swirling dresses and hats the size of manhole covers passed from the nickel glitter of traffic to the crystal glitter of the lobby.

In front of the Lorraine and the St. Regis, and swarming about the mad-hatter doorman under the warm orange lights of the Biltmore facade, were hundreds of girls with marcel waves, with colored shoes and orchids, girls with pretty faces, dangling powder boxes and bracelets and lank young men from their wrists—all on their way to tea. At that time, tea was a public levee. There were tea personalities—young leaders who, though having no claim to any particular social or artistic distinction, swung after them long strings of contemporary silhouettes like a game of crack-the-whip. Under the somber, ironic parrots of the Biltmore the halo of golden bobs absorbed the light from heavy chandeliers, dark heads lost themselves in corner shadows, leaving only the rim of young faces against the winter windows—all of them scurrying along the trail of one or two dynamic youngsters.

Caroline was one of those. She was then about sixteen, and dressed herself always in black dresses—dozens of them—falling away from her slim, perfect body like strips of clay from a sculptor’s thumb. She had invented a new way to dance, shaking her head from side to side in dreamy, tentative emphasis and picking her feet up quickly off the floor. It would have made you notice her, even if she hadn’t had that lovely bacchanalian face to turn and nod and turn away into the smoky walls. I watched her for ages before I asked who she was. There was a sense of adventure in the way her high heels sat so precisely in the center of the backs of her long silk legs, and a sense of drama in her conical eyebrows, and she was much too young to have learned such complete self-possession in any legitimate way.

Her story, to date, was short and hysterical—a runaway marriage—annulled immediately—a year in small parts on the New York stage, and the scandalous journalism that followed that affair of Brooklyn Bridge. It must have demanded a good bit of vitality to bring all that to the attention of so many people in such a short time, especially since she started out empty-handed, equipped with only the love and despair in her father’s vague eyes. He was one of those people who distinguish themselves in an obscure profession, and Caroline was far from considering Who’s Who an adequate substitute for the Social Register. She was ambitious, she was extravagant, and she was just about the prettiest thing you ever saw. I never could decide whether she was calculating or not. I suppose any young person in a red-flower hat who suddenly, in the midst of an undergraduate hullabaloo, meets the heir to fantastic millions, and who thereupon smiles poetically into his brown eyes, could be called calculating, but Caroline had made the same gestures so many times before without material considerations.

They looked fine together; they were both dusted with soft golden brown like bees’ wings, and they were tall, and the color under their skins was apricot, and there was harmony in the way he leaned forward and she leaned back against the red-leather bench. You could see that he was rich and that he liked her, and you could see that she was poor and that she knew he did. That, at their first meeting, was all there was to be seen; though psychics might have found an aura of tragedy whirling above their two young heads even then. They seemed too perfect.

The winter got old and frayed the edges of the palms in the quiet clinking of the Plaza lobby. The steam heat twisted their tips into little brown mustache ends, and people waiting for other people ripped short slits about their lower leaves. Caroline had worn out two big branches since the day she discovered that Barry was not even regular about being late. It was a nuisance, that; it meant that she had to sit there rigid, being stared at by men without knees, in spats, and bellboys without necks, in billiard-table covers, and clerks without shoulders, in cages, while Barry did something somewhere to one of his automobiles. He had three, so underslung that riding in them was like climbing a mountain in a cable car. They used to go together for mad rides up and down Long Island, or splitting the green of Connecticut hills in the spring; Caroline so lost in the snakeskin cushions that she seemed deflated; Barry steering the monstrous thing as if he were sketching in charcoal, and both of them singing chorus after chorus of monotonous Negro blues.

One late winter Sunday when the glare of the afternoon snow forced the shadows into great banks in the corners of the living room, Caroline and Barry drove out to see us. They came in breathing off a refrigerated crispness of lettuce just off the ice chest; the moisture on the tips of their long-haired furs refracting the hall lights to a purplish halo.

“Hello,” she said. “Is this Fitzgerald’s roadhouse?”

Her voice was as full of varied emotions as sinking into a soft cold bed after a strenuous day. Over its voluptuous nuances brooded the purring monotone of well-bred New York.

“It is,” I affirmed, “and there’s cold turkey and asparagus for supper; so come in and get warm while you wait.”

Barry sat under the one light in the far end of the long living room, turning over a great pile of phonograph records, and Caroline sat rigid in the pink shadows, both of them so conscious of each other that they gave the impression of two hidden enemies waiting to attack. We listened to the big logs popping in the quiet like wet firecrackers, and to the clinking of the furnace being fixed for the night, and to the sound of a bath running on the second floor. Supper was being laid in the dining room opposite, and an intimate unwarranted friendliness stole into our low monosyllabic conversation. I felt like reciting “ ’Twas the night before Christmas” and going to sleep on the rug, when suddenly Barry, from way over there under the light, asked Caroline to marry him. The slow dignity of her acceptance made us realize the seriousness of the affair; there was nothing to do but try to garnish our Sunday scraps into an engagement supper.

They were both absorbed and quiet during the meal, and, not knowing quite what to say, I began thinking of all sorts of things—of Caroline the winter before, in creamy white georgette and a fog of gray squirrel, coming down the steps of a narrow Fifth Avenue mansion, freezing her tears on the clear winter air. It was a debut party, and she had tried crashing too formidable a gate. New York butlers are not hired for their response to beauty and this one had turned her away decisively. I thought of Barry calling for his mother at an embassy tea in Rome—of Barry, nineteen, elegant, impeccable, preferred of all the mothers of girls whose families chose for them their paths of light. He was spoiled and wild, but since he had probably met Caroline on some sort of jag, that was no reason why there should be any miscomprehension between them on that score. I wondered how he would explain his intimacy with so lovely and scandalous a person to his austere family, and if they would accept Caroline with no matter what explanation he could invent.

That winter to me is a memory of endless telephone calls and of slipping and sliding over the snow between the low white fences of Long Island, which means that we were running around a lot. We met Caroline and Barry in town occasionally, in the aquarium lights of an expensive nightclub or under the glare of a theater portico. People said they were always together and never went out without each other. She was one of the few women I’ve known who was both fluffy enough and concise enough to look pretty in ermine, and when you saw them stepping together into his huge automobile it made you think of musical comedy principalities or glamorous suppers from Renaissance paintings.

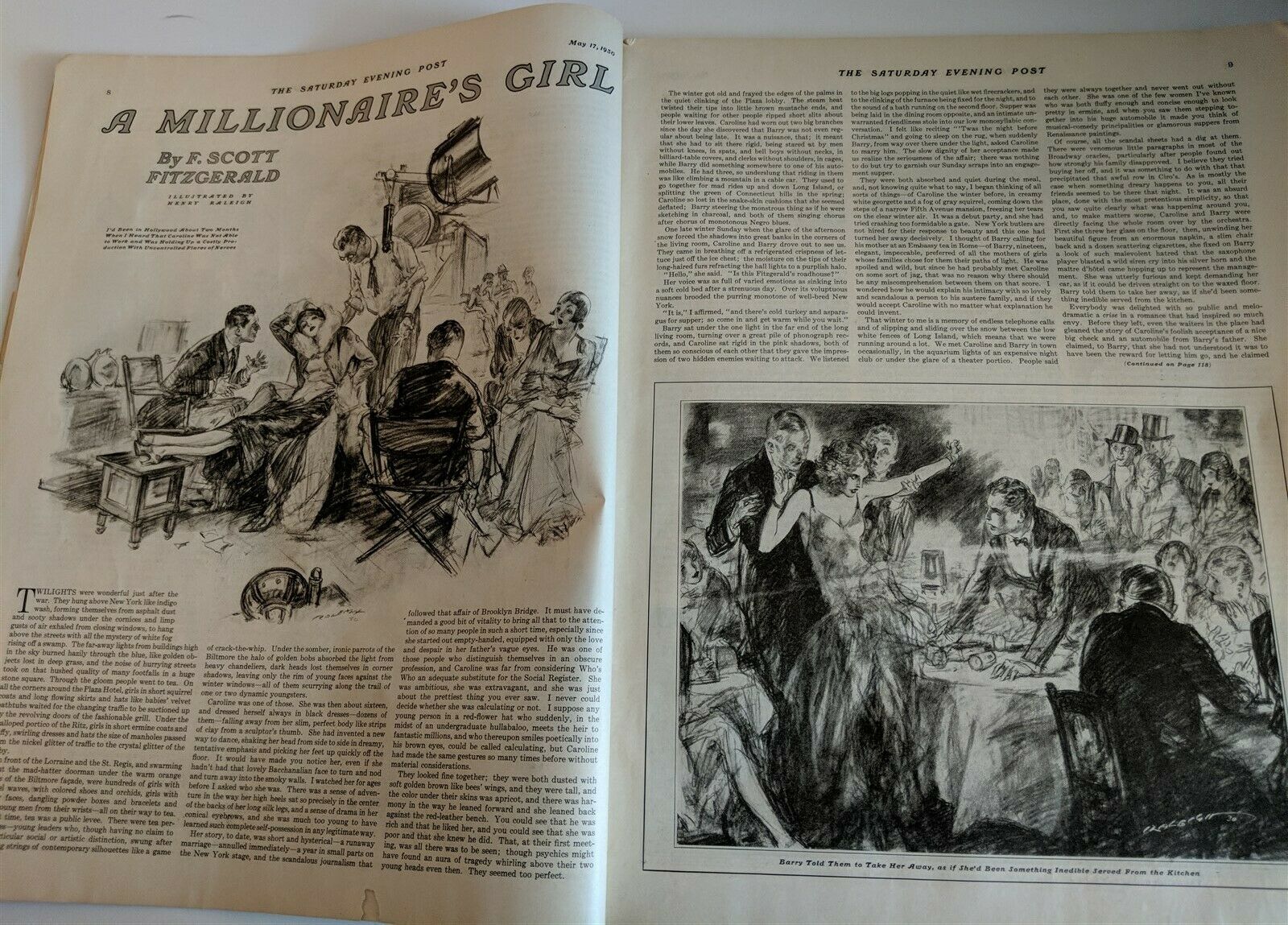

Of course, all the scandal sheets had a dig at them. There were venomous little paragraphs in most of the Broadway oracles, particularly after people found out how strongly his family disapproved. I believe they tried buying her off, and it was something to do with that that precipitated that awful row in Ciro’s. As is mostly the case when something dreary happens to you, all their friends seemed to be there that night. It was an absurd place, done with the most pretentious simplicity, so that you saw quite clearly what was happening around you, and, to make matters worse, Caroline and Barry were directly facing the whole room over by the orchestra. First she threw her glass on the floor, then, unwinding her beautiful figure from an enormous napkin, a slim chairback and a dozen scattering cigarettes, she fixed on Barry a look of such malevolent hatred that the saxophone player blasted a wild siren cry into his silver horn and the maitre d’hotel came hopping up to represent the management. She was utterly furious and kept demanding her car, as if it could be driven straight on to the waxed floor. Barry told them to take her away, as if she’d been something inedible served from the kitchen.

Everybody was delighted with so public and melodramatic a crise in a romance that had inspired so much envy. Before they left, even the waiters in the place had gleaned the story of Caroline’s foolish acceptance of a nice big check and an automobile from Barry’s father. She claimed, to Barry, that she had not understood it was to have been the reward for letting him go, and he claimed in no uncertain terms that she was fundamentally, hopelessly, and irreclaimably dishonest. It seems too bad they couldn’t have done their claiming at home, because then they might have patched up the mess. But too many people had witnessed the scene for either of them to give in an inch.

Several days later Barry shut the bumpings and thumpings of the embryo delirium tremens that usually follows a complete disillusionment into a golden-oak suite of one of the biggest transatlantic liners, en route for Paris. Two weeks later, as I was bumping along the walnut panelings of a transcontinental express on my way to California, I slipped along the rounded corner and bang into Caroline. I don’t know how I had expected to find her, but I was terribly surprised with her air of elegant martyrdom. She was royalty in exile. From the slope of her shoulders to the eloquent inactivity of her hands her whole person cried out, “This is the way I am, and I’m going to stick by it.” Now I knew that Caroline had not a bit of that fading-violets, closing-episode note of the minor lyric poet that makes people run from things in her erstwhile personality, and I wondered what determination had sent her scurrying from a world that she knew, but that didn’t know her, across a continent to a world that knew her from her escapades, but that she didn’t know. It seemed to me an unreasonable exchange. If it was not escape that motivated her, then it must be vengeance, I told myself, and it was all I could do to keep from asking her on the spot.

Thinking of that long ride to California, it does not appear remarkable that people should lose their sense of proportion on the way. The pattern of the tracks at the beginning lies like featherstitching along the borders of a land suggesting the tin scenic effects that are sold with mechanical trains; a green and brown hill, a precipitate tunnel, a brick station too small for the train, an odd gate, a lamppost, and a little lead dog. The first night there is a feeling of accomplishment that you are installed in your apple-green compartment, moving in a phosphorescent line through the red and purple streaks of a Western dark. The dining car glistens with bright new food; the train is still a part of its advertising pamphlets and has not yet settled down to its own dynamic ends. You can still smoke without tasting brass cartridges in the back of your mouth. I didn’t see Caroline at first, to victimize her by my curiosity. We were both fascinated by the limitations of life on the train, probably; but later, when even Mr. Harvey’s ingenuity could invent no name for hash-brown potatoes exotic enough to tempt our cindery palates, we sat in mutual lamentation amongst the catsup bottles and vinegar cruets of the diner.

The countryside was changing. The faraway hills did not meet the horizon, and the trees and houses on the green mountainsides seemed on probation. Caroline was suddenly fed up with the quiet reserve that her getting-away-from-it-all manner had imposed upon her and was bursting to talk. She told me she had a part in a movie and was going west to work. In the course of a long conversation I gathered that she was completely determined to distinguish herself and force Barry to realize the enormity of his error in leaving her so precipitately. She talked and talked, fascinating herself with the idea of success, until by the end of the trip I think she never wanted to see me again, so full had she filled me with her hopes and plans. I could see her changing personalities behind the first onrush of people in the Los Angeles station, marking herself with the silent wary confidence so necessary in a world of competitive struggle.

We found ourselves at the same hotel. About the central mass there lay shimmering in the rarefied sun low lines of bungalows like the tentacles of a sea monster crystallizing itself in the humid heat. Grass like wet paint covered the gushing squares of earth between the cement paths in the court, and from one doorway to another white rose vines stretched and aspired along a trellising of flaky zinc pipes. Caroline’s rooms were opposite mine, and I could tell by the number of waiters who were always scurrying in and out that she was auspiciously launched in her new milieu. I had to pass her door on my way in, and there was always a paper envelope hanging on her knob, bulging with telephone messages. More and more often there were yellow roses under the yellow curtains at her window. I knew which director preferred yellow roses and referred to them, amusingly, as “radishes.”

Sometimes I burrowed my way through the candy stores and barbershops and glass cases filled with the curlicues of Oriental art to the great supper room of the hotel. There, in the brightly lit darkness of an artificial Hawaii, was always Caroline, sitting, listening, elegant and fragile, connaisseuse of perfumes and parades. People knew her by name; her career was getting under way. She drank little and spent the mornings having herself pummeled and pounded into a nervously receptive state that was, for film purposes, the equivalent of dramatic ability. She learned to accentuate a slight defect in her lovely face with heavy makeup, so that her wide cheekbones gave her a Tatar look under the creamy powder. She learned to be distrait and aloof and passed those two qualities off as sophistication and disillusionment. Hollywood was captivated. I’d been out there about two months when I heard that Caroline was not able to work and was holding up a costly production with uncontrolled flares of nerves. I concluded she was about to get fired, so I ran to stick my finger in the pie. I persuaded her to drive to the sea with me.

I don’t know what there is about California that makes it seem so inland. I suppose it’s that sparse attempt to enclose so much space with two orange trees and an oil well. Anyway, I felt that it would do her good to escape that feeling of being in a vacuum that the wide-spaced city gives me, and she had never seen the Pacific, so we hired an open car and became part of an unbroken line of automobiles weaving along under the vast sky, like an invasion of beetles, toward Long Beach. She was hardly interested in the flatness of a country that was bright like a dirty mirror from its lack of color in the sun, and I could see that the chauffeur’s fast driving made her nervous. Having wrecked my own nerves years ago, I like advising other people about their own.

“You’re going too hard,” I told her, “and if you keep on living at such tension that you can’t sit in an automobile without grabbing the sides you won’t last long at your work.” The sun curved along her high cheekbones and dug a white triangle under her lifted chin. A big bunch of pink sweet peas tattered themselves against the brim of her white felt hat in the wind and blew against her shining face as she turned and cheerfully agreed with me that she would probably collapse before long.

“But it isn’t the work,” she said enigmatically.

“Oh, gosh,” I thought, “she’s going to start proving she’s right again.”

We had luncheon in a dingy dining room facing a brick wall, with pictures of the ocean painted about the ceiling. There was nowhere else in Long Beach on the sea to have luncheon, since nonalcoholic races are too suspicious of reality to face even the ocean. We both tried temporizing with a soggy shrimp cocktail. Caroline leaned over the table and asked me suddenly for news of New York in such an apologetic, eager way that I sensed what she really wanted to talk about. It was Barry. People had, naturally, avoided the subject with her, I suppose, and I was feeling complacent enough to say what she wanted.

“Aren’t you over that yet?” I asked.

She smiled with detached desperation.

“Oh, yes, of course, but I hate to lose touch with him,” she answered. “Ever since I met him everything I do or that happens to me has seemed because of him. Now I am going to make a hit so that I can choose him again, because I’m going to have him somehow. I wanted to say that to somebody, so I’d have to do it. I’m sorry to spoil your ride, but it’s made me able to go back to work again. You see, I haven’t any friends,” she finished simply.

When she left me at the door of her bungalow that night so much sadness sank into the shadows about her eyes and so much unsurety sounded in her footfalls along the cement steps that a surge of hatred swept over me against trim seaside hotels, and even old Balboa, and the East and the West and love affairs. As she climbed the stairs the heels of her slippers echoed as if the shoes were empty. I spectrally crossed over the fog to my own door.

Next day it began to rain in California, much against the better judgment of the most influential citizens—not just ordinary rain the way it rains in other places, but great brown bulks of water flowing down the gutters like hot molasses candy. At the bottom of hills where two streets met, the water came up to the running boards of automobiles. It seethed through umbrellas in a fine spray and covered the sidewalks with slippery mud deltas. If the sun came out for a minute the air steamed with hot vapor and the sodden cushions of grass smoked under its discouraged rays. Naturally, going about was unpleasant, so I spent most of my time in my room, washing down quantities of spring onions and alligator pears with California Bordeaux. When I traveled the flood again Caroline’s picture was finished and March was powdering the air with spring dust. I had heard talk about the film; apparently she came off with flying colors. The director had been so pleased with her work that, with the final assembling of the picture, her part had grown to star proportions, and there was nothing between her and a successful career. I was pleased that she was glad to see me again and that she gave me seats to the opening. It was surprising that such a prospect hadn’t erased that distant distress in her eyes but had only superimposed an air of excitement on the placidity of her lovely white features.

A Hollywood opening night is a fairy-tale affair. A street is flooded with blue-white diamond light that glints over the trees and lies like mica over their foliage and along their trunks. There are festoons of ordinary lights like strings of golden oranges swung from pole to pole in the ether whiteness, and all is broken into a million cones and triangles by the headlights of hundreds of automobiles. The shadows fall short about their objects—thick gluey puddles under the cars and people. A red carpet bridges the pavement between automobiles and the theater door, and grinding cameras envelop the arriving celebrities. A gigantic megaphone cries out famous names to the crowd waiting on the edge of the light, and they, in turn, respond with loud applause or rustling silence—a sort of trial by fire. Fine, uncharitable ladies in silver shoes and ermine may be greeted with protesting murmurs from under the trees, and gay young girls in coral velvet that people know have helped their kind may start the clatter of many hands swelling from far around the corner, in the approval of a public that considers itself humanitarian.

There is no expectancy in the air; it is the dumb hero worship of fans gathered in the gloom like medieval serfs awaiting a conquering baron that dominates the atmosphere—that and the shining assurance that insecure people must assume in places of authority. I had never been to an opening before, so I stood for an hour watching from across the way. It was like an elegant feminine circus breaking ground. I wanted terribly to see Caroline come in. It was her night, and I knew she would have something amusing to contribute—some little unpretentious trick of pinning her flowers in an unexpected corner, of forcing her hair to interrogative angles, of wearing some funny thing like a dagger, or a tiny bell at the side of her slippers—but the line of cars moved faster and faster before the door and the cheaper cars were making their appearance, so I knew I’d be late if I didn’t go inside.

The picture was fine. Caroline’s beautiful biblical eyes dimmed and shone over teacups and decanters and through the spray of shower baths and dominated the mists of a good art director. I felt a secret jealousy of such assured success. I came outside in the entr’acte to see if I could find her in the crowded lobby. She was nowhere around, and feeling rather gloomy at being alone among so many people using so many adjectives, I went along bareheaded through the moist spring air to the corner drugstore. It was like all drugstores—gift cases of perfume and powder, writing paper and books, round tables of incense burners and picture frames and all the things you couldn’t imagine buying in a drugstore—and I don’t know why that sudden sense of disaster came over me. I felt as if I were in an exiled and floating world, isolated from all necessities of life except the one of buying things. To bring myself back to reality I went to the cigar counter and chose the late edition of an evening paper. On the front page was a big picture of Barry and his fiancee, telegraphed from Paris. HEIRS OF TWO GREAT FORTUNES TO HAVE QUIET CEREMONY. I was glad Caroline had made such a killing in the film and I wondered if she’d mind much when she saw those blaring headlines.

The picture was thoroughly amusing. There was always that horizon quality in her eyes, and nobody ever had a more symmetrical body to help her to stardom, or one that she could work so well. It was like a splendid mechanical installation in its trim, impersonal fitness. Toward the end she surprised me with an intensely moving scene—some sort of stuff about two young lovers being separated by a misunderstanding. The audience was moved and would have been even more affected, I think, except for the violent clanging of an ambulance bell, jarring throughout the quiet of a pathetic episode. It was a pity; it took half the value away from the scene.

Next morning I hurried out for all the papers, from a malicious curiosity to see whether Caroline or Barry would have the choicest space. She won, hands down. The dramatic columns were full of laudatory accounts of the film, obviously written the night before; and the front pages were full of last-minute headlines and two-column stories of her attempted suicide on the night of her successful debut. The sob sisters made a very dramatic episode out of her clanging past the theater in an ambulance on the opening night.

Two weeks later, when she was well enough to receive visitors, I called at the hospital to see her. I almost had to engage a room for myself when I ran into Barry. For he was there, very solicitous and proprietary, and you’d never have guessed from his manner that he was responsible for her half death or half responsible for her death, so I didn’t stay long. I left, pondering all the way back to town over the wonders that long-distance telephones and a dramatic sense can accomplish when brought in close proximity. One of those friends that Caroline disclaimed must have called up Paris for her.

She married him, of course, and since she left the films on that occasion, they have both had much to reproach each other for. That was three years ago, and so far they have kept their quarrels out of the divorce courts, but I somehow think you can’t go on forever protecting quarrels, and that romances born in violence and suspicion will end themselves on the same note; though, of course, I am a cynical person and, perhaps, no competent judge of idyllic young love affairs.

Published in The Saturday Evening Post magazine (May 7, 1930), published as by F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Illustrations by Henry Raleigh.