The Continental Angle

by Zelda Fitzgerald

Gastronomic delight and sartorial pleasure radiated from the two people. They sat at a table on a polished dais under a canopy of horse chestnuts eating of the fresh noon sunlight which turned the long, yellow bars of their asparagus to a chromatic xylophone. The hot, acrid sauce and the spring air disputed and wept together, Tweedledum and Tweedledee, over the June down that floated here and there before their vision like frayed places in a tapestry.

“Do you remember,” she said, “the Ducoed chairs of Southern tearooms and the leftover look of the Sunday gingerbread that goes with a dollar dinner, the mustardy linen and the waiters’ spotted dinner coats of a Broadway chophouse, the smell of a mayonnaise you get with a meal in the shopping district, the pools of blue milk like artificial opals on a drugstore counter, the safe, plebeian intimacy of chocolate on the air, and the greasy smell of whipped cream in a sandwich emporium? There’s the sterility of upper Broadway with the pancakes at Childs drowned in the pale hospital light, and Swiss restaurants with walls like a merry-go-round backdrop, and Italian restaurants latticed like the lacing of a small and pompous Balkan officer, and green peppers curling like garter snakes in marshy hors d’oeuvre compartments, and piles of spaghetti like the sweepings from a dance hall under the red lights and paper flowers.”

“Yes,” he said, but with nostalgia, “and there are strips of bacon curling over the country sausage in the luminous filterings from the princely windows of the Plaza, and honeydew melon with just a whiff of lemon from narrow red benches that balustrade Park Avenue restaurants, and there’s the impersonal masculinity of lunch at the Chatham, the diplomacy of dinner at the St. Regis; there are strawberries in winter on buffets that rise like fountains in places named Versailles and Trianon and Fontainebleau, and caviar in blocks of ice.”

“If you eat late on Sunday at the Lafayette,” she continued blandly, “the tables are covered with coffee cups and the deep windows let in the wheezing asphalt and you look over boxes of faded artificial flowers onto the tables where people have eaten conversation and dumped their ashes in their saucers while they talked, and at the Brevoort men with much to think about have eaten steak, thick, chewing like a person’s footfalls in a heavily padded corridor. In all the basements where old English signs hang over the stairs, years ago they buried puddings, whereas if you have the energy to climb a flight of stairs, there are motherly nests of salad and perhaps something Hawaiian.”

“Ah, and at Delmonico’s there were meals with the flavor of a transatlantic liner,” he said; “at Hicks there are illustration salads, gleaming, tumbling over the plate like a raja’s jewels, cream cheese and alligator pear and cherries floating about like balls on a Christmas tree. And filet de sole paves the Fifties, and shrimp cobbles Broadway, and grapefruits roll about the roof and turn roof gardens to celestial bowling alleys. There is cold salmon with the elegance of a lady’s boudoir in the infinity of big hotel dining rooms, and Mephistophelean crab cocktails that give you the sweat of a long horseback ride and pastry that spurts like summer showers in restaurants famed for their chef.”

“And there are waffles spongy under syrups as aromatic as the heat that rises in a hedged lane after a July rain, and chicken in the red brick of Madison Avenue,” she pursued. “And I have eaten in old places under stained glass windows where the palm fronds reflected in my cream of tomato soup reminded me of embalming parlors, and I’ve gulped sweet potatoes in the Pennsylvania Station, ice tea and pineapple salad under the spinning fans blowing travelers to a standstill, tomato skins in a club sandwich and the smell of pickles in the Forties.”

“Yes,” he said, “and raspberries trickling down the fountain at the Ritz, bubbling up and falling like the ball in a shooting-gallery spray, and eggs in a baked potato for ladies and——”

“Pardon, est-ce que Madame a bien dejeune?”

“C’etait exquis, merci bien.”

“Et Monsieur, il se plait chez vous?”

“What the hell did he say, my dear? I learned my French in America and it doesn’t seem to be completely adequate.”

“Ah, sir, I understand perfectly. I be so bold as to ask if Monsieur like our restaurant, perhaps?” answered the waiter.

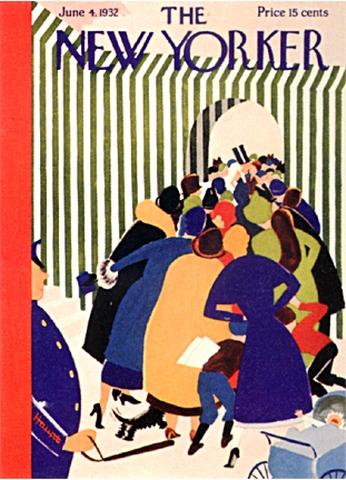

Published in The New Yorker magazine (June 4, 1932).

Not illustrated.