“The Last of the Novelists”: F. Scott Fitzgerald and The Last Tycoon

by Matthew J. Bruccoli

4/ The Drafts

When Fitzgerald began writing The Last Tycoon in 1939 hehad not worked on a novel for five years; and after 1935 he was no longer able to write the 5,000-word commercial-length short story, a form he had mastered in the twenties. The Fitzgerald/Ober correspondence reveals that the Post-type stories Fitzgerald tried to write after Tender Is the Night required extraordinary editorial assistance, and that even with such help some were salable only because Fitzgerald’s name was on them. During the 1937-40 Hollywood period he published short-shorts in Esquire, few of which had any distinction. This form appealed to Fitzgerald because it did not require an extended effort. A short-short of 1,500-2,500 words could be written in one or two sittings, and presented no structural problems, for most of these pieces were expanded anecdotes.

Hollywood did not ruin Fitzgerald as a writer. The prose of The Last Tycoon shows no damage to Fitzgerald’s style. Nonetheless, it is likely that screenplay work affected his structural powers. The technique of the screenplay is scenic and episodic. The screenwriter is writing for the camera, with the knowledge that the structure and pacing of the movie will be achieved through editing the film. Moreover, many screenwriting assignments are piece-work, requiring the writer to work on individual scenes. It seems clear that Fitzgerald had become accustomed to thinking in episodes by 1939. After Chapter I Fitzgerald was not writing chapters, but episodes for the novel.

The opening of a novel is the hardest part for a writer because itinvolves building in preparatory material and making decisions about point of view and structure that will affect the rest of the work. Fitzgerald’s problems with the first chapters of the novel are instructive. Only when he stopped trying to shape chapters did the writing progress rapidly. Beginning with episode 7 of Chapter 2, Fitzgerald wrote only episodes or sections. (In this study the chapter designations after Chapter 1 refer to the chapters Edmund Wilson assembled from the episodes.) It is too simple to claim that the shift to episodes accounts for the relative speed with which Fitzgerald’s work progressed after Chapter 2. There is another factor involved—Fitzgerald’s sense of urgency. When he resumed full-time work on the novel in the summer of 1940 after interrupting it for the “Babylon Revisited” screenplay, he had imposed a December deadline on himself. Initially this deadline was determined by finances as well as by his strong desire to re-establish himself as a novelist. But after his first diagnosed heart attack in November 1940 he had a sense that he was writing against the clock. Instead of trying to polish each chapter as it was written, Fitzgerald decided to push through to a complete draft, which he would then rework. All of his life Fitzgerald had been a painstaking reviser, and there is no reason to suppose that he regarded the episodes of this novel as anything more than working drafts.

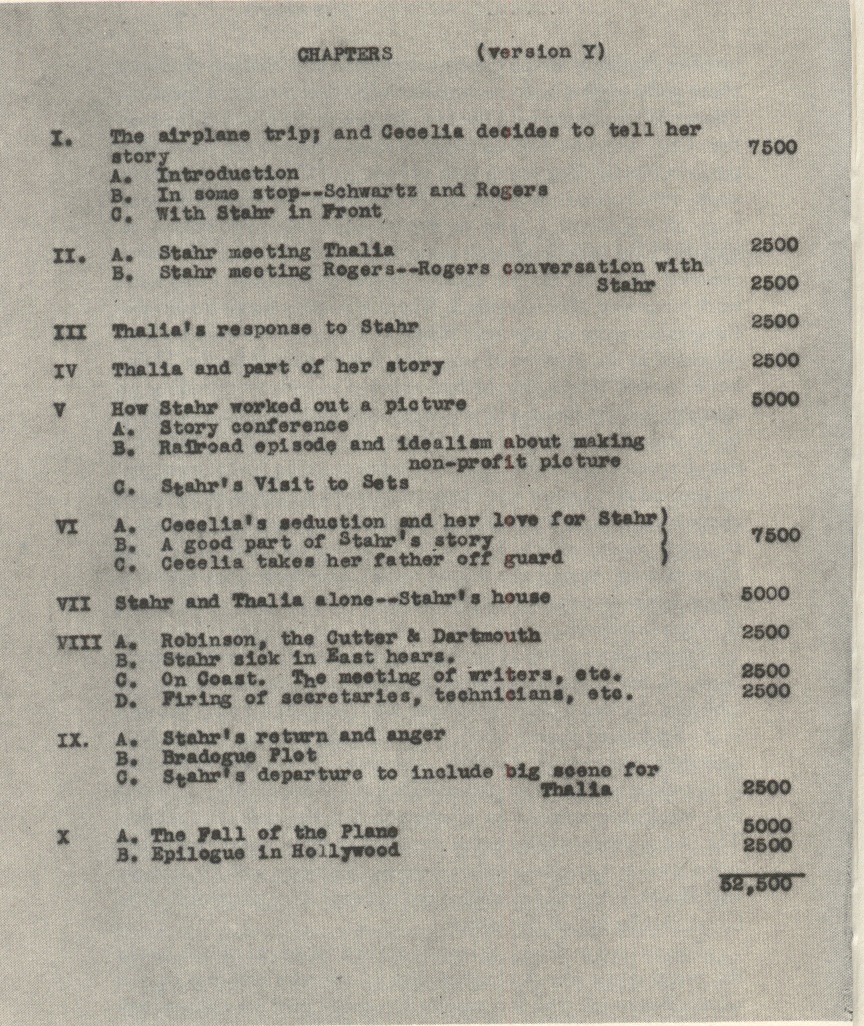

Fitzgerald’s outline-chart for the novel exists in five versions. None of the outlines is dated, but the order can be clearly established on the basis of structural alterations and name changes (e.g., Bradogue [ Baird [ Brady). The earliest surviving outline is an unrevised typescript headed “(version Y)”—indicating that Fitzgerald regarded it as a preliminary form of the outline. This version breaks the action into 10 chapters but has only 23 episodes. The plot is substantially that of the latest outline, consisting of two interconnected stories—Stahr’s love for Kathleen and his struggle with Brady. Fitzgerald estimated the material at 52,500 words. (The Great Gatsby has 48,852 words.)

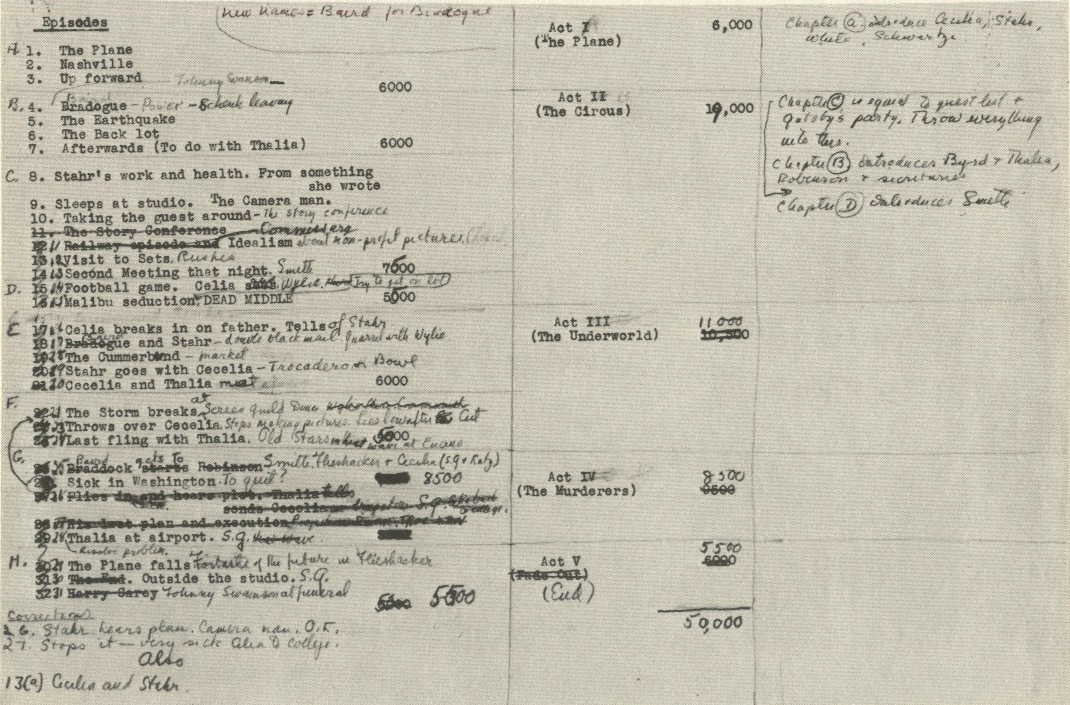

The second outline is a heavily revised typescript which breaks the novel down into 8 chapters and 31 episodes totalling 50,000 words. Beginning with this version Fitzgerald used a 3-column format: a column of episodes; a column indicating a 5-act structure; and a column of commentary.

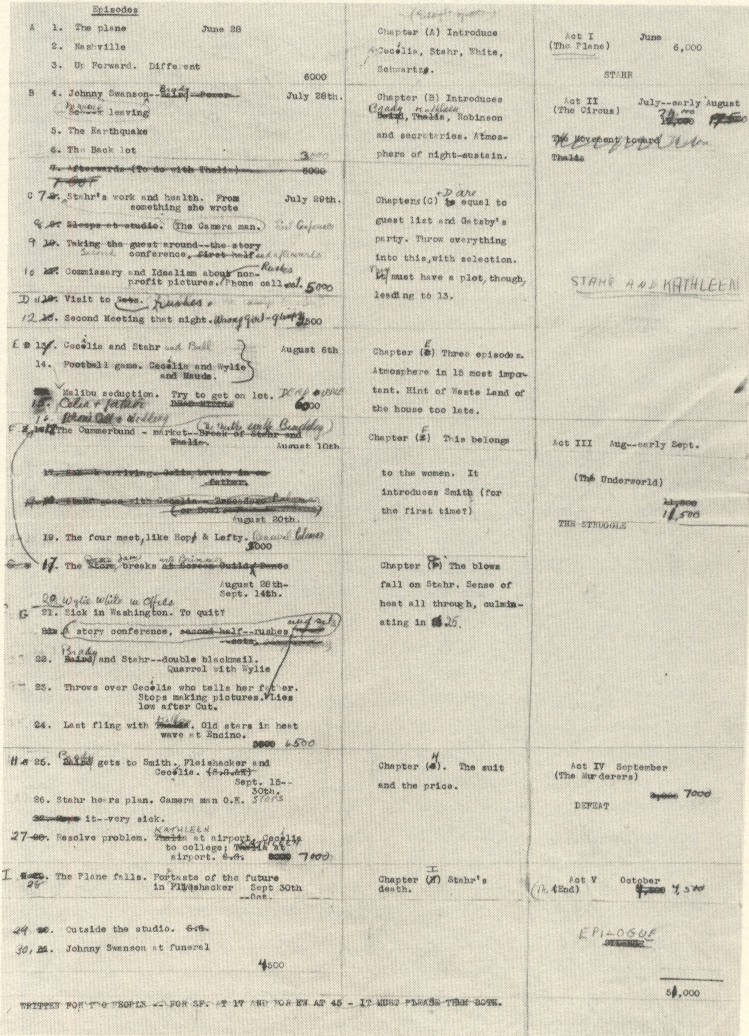

The third outline—a revised typescript—is an elaboration of the second. The structure is still 8 chapters of 31 episodes; but Fitzgerald added dates indicating the pacing of the action from 28 June to 30 September. At the bottom of this outline-chart Fitzgerald noted in holograph: “Written for two people—for F. S. F. [Scottie Fitzgerald] at 17 and for E. W. [Edmund Wilson] at 45—it must please them both.”

In the fourth outline—a revised typescript—Fitzgerald achieved the 9 chapter / 30 episode structure principally by cancelling episode 7 for “Afterwards (To do with Thalia).” This projected episode followed the rescue of the girls in the flood, and the manuscripts show that Fitzgerald originally planned to extend the first meeting between Stahr and Kathleen (Thalia). Episode 17 ( “Schenk arriving. Celia breaks in on Father.”) and episode 18 (“Stahr goes with Cecelia—Trocadero or Bowl.”) were also cancelled; and episode 20 was added ( “Wylie White in Office”). The fifth and latest outline is an unrevised typescript of the fourth version.

Edmund Wilson used Fitzgerald’s latest outline for the outline printed in The Last Tycoon, but he emended it. Wilson omitted from episode 13 the note on “Football game. Cecelia and Wylie and Maude.” He changed the dates for episodes 17-18 and 20-21. He deleted the references to S. G.—an obligatory change because Fitzgerald’s relationship with Sheilah Graham was not generally known in 1941. Finally, he omitted Fitzgerald’s note about writing a novel that would have to please both Scottie and Wilson.

The compositional method Fitzgerald employed for The Last Tycoon was his customary method of polishing his work through levels of revision. The first draft was always in holograph. Fitzgerald wrote in pencil on legal-size pads; he never worked on a typewriter. The holograph would be typed by a secretary—the typing for The Last Tycoon was done by Frances Kroll, his secretary in the 1939-40 period—usually with two carbon copies and sometimes with three. Fitzgerald would then heavily revise one or more of these typescripts, turning the one he preferred over to the typist for retyping. This process might continue through as many as four or five complete typescripts. Then he would revise again in proof. For an analysis of Fitzgerald’s writing methods, see Bruccoli, The Composition of Tender Is the Night (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1963) and The Great Gatsby: A Facsimile of the Manuscript (Washington: Bruccoli Clark/Microcard Editions Books, 1974).

Some 1100 pages of drafts for the novel survive, including all typescripts and carbon copies. In addition, there are more than 200 pages of notes and related material.

In the inventory of drafts provided here, manuscript always means holograph. When a draft is typed, it is always called a typescript. Ribbon typescripts and carbon copies are differentiated. Revised means revised by Fitzgerald. Bracketed page numbers are inferential. Parenthetical paginations indicate Fitzgerald’s own custom of replacing two or more pages with a single page: (30-31) indicates that he deleted pages 30 and 31 and replaced them with a page he numbered 30-31 for the benefit of the typist. A single bracket stands for “changed to.” Thus #2 [v.3 means that Fitzgerald changed the draft designation from “2” to “v. 3 “—with “v.” signifying “version.” In the inventories that follow, the letters A, B, C, etc. are not Fitzgerald’s; they have been supplied as a convenience for identifying draft stages or segments. The latest typescript for each episode is identified in the inventory, and it is always the copy-text used in Edmund Wilson’s edition of The Last Tycoon.

In preparing Fitzgerald’s typescripts for publication Wilson renumbered the pages and sometimes altered the episode headings. Wilson’s handwriting can be differentiated from Fitzgerald’s, but, it is not possible to identify the source of cross-outs.

In this study the manuscripts and typescripts are transcribed exactly. Passages or words Fitzgerald crossed out or deleted are enclosed in angle brackets. In a few cases where the deleted material is unrecoverable, empty angle brackets are used.

Chapter I

- A Manuscript. [1]—54 (54-55) 56-66 “Chapter I.”

- B Revised Typescript & Manuscript. [1]—13 [14-15] 16-, [33-35]. “CHAPTER I.” #1

- C Revised Carbon Copy. [1]-4 [ ] 5-25. With shorthand notes. “CHAPTER I.” #1

- D Revised Typescript. [1]-8, insert 8, 9-10, 10½, 11-21, 21½, 22-24, 24, 25. “CHAPTER I.” #2 [ v.3

- E Carbon Copy. [1]-25. “CHAPTER I.” #2

- F Typescript. [1]-17, 17A, 18-24. “CHAPTER I.” #v.3

- G Carbon Copy, [1]-17, 17A, 18-24. “CHAPTER I.” #v.3

- H Revised Carbon Copy. [1]-17, 17A, 18-19, 19½, 20-24, 24. “CHAPTER I.” #v. 3 [v.4

- I Revised Typescript. [1]-25. “CHAPTER I (Episodes 1, 2, 3).” #v. 4 Latest Typescript.

Variant opening: ( “—It was still ’roses, roses all the way’ down to 1935—”) - J Manuscript. 4-6 [7]. “Chapter I”

- K Typescript. 5-7. “CHAPTER I.” #1

- Sanitarium Frame

- L Revised Typescript, [1]-3. #3

- M Carbon Copy. [1]-3. #3

- N Revised Typescript. [1]-3. #4

- O Carbon Copy. [1]-3. #4

- P Revised Typescript. [1]—4. #5

- Q Typescript, [1]-3. #6.

- R Carbon Copy. [1]-3 #6

- Outline

- A 1. The plane June 28th

2. Nashville

3. Up forward. Different

On the basis of the surviving drafts, Chapter 1 (corresponding to episodes 1-3) gave Fitzgerald little trouble. But the evidence is incomplete, for it is almost certain that there were discarded early starts—see segments J and K. The first extant draft (A) for this chapter consists of 66 holograph pages up to Stahr’s conversation with the pilot, breaking off with: “ ’Look, you’ve got ect. see copy.” The material is complete up to that point—with no serious holes and no important material that was subsequently cut. The inserted typed page numbered (54-55) that describes Stahr’s boyhood indicates that Fitzgerald probably had other early drafts that he conflated into this long holograph draft. Cecelia’s last name here is Bradogue, which Sheilah Graham informed Edmund Wilson was changed because Fitzgerald decided it was too harsh-sounding. He changed it to Baird and then Brady. Wylie White was originally named Rogers Carling. There is a problem in this first draft that remains in the subsequent drafts: Cecelia does not recognize Mr. Smith as Stahr when she first sees him on the plane. While it is true that she sees only his back, she does hear his voice; and she knows him very well. The obvious explanation is that Fitzgerald wanted to delay introducing Stahr to the reader in order to develop some curiosity about him; but the technique is a bit clumsy.

The Manny Schwartze material remained substantially unchanged in the drafts of Chapter 1, indicating that Fitzgerald was apparently satisfied with it. Nevertheless, Schwartze’s function in the novel is not clear. At one point Fitzgerald seems to have planned for Schwartze to tell Stahr something that Stahr uses against Brady in the unwritten blackmail episodes, since the memo on the roadhouse raid has Fitzgerald’s holograph note “For Schwartze.” The main problem with the Schwartze material is that it introduces Stahr as a callous figure—which he is not. Schwartze commits suicide after Stahr rebuffs him, leaving a note for Stahr saying that he knows it is no use if Stahr has turned against him. While the suicide conveys a sense of the respect in which Stahr is held, it is difficult to justify in terms of the novel’s action. The only way in which Schwartze can be said to function in the plan of the novel is that his attempt to warn Stahr of a plot against him prepares the reader for the power struggle between Brady and Stahr, but this information is not really required in Chapter 1. Perhaps Fitzgerald was attracted by the symmetry of opening and closing the novel with deaths: Schwartze commits suicide during a plane trip, and Stahr will die in a plane crash. Sheilah Graham’s 11 January 1941 letter to Maxwell Perkins explains that Fitzgerald had decided to either cut out Schwartze “or find some way of bringing him into the rest of the book.”

The 32-page ribbon typescript (B) prepared from the holograph was designated draft 1 or version 1. It was heavily revised, and 4 holograph pages were inserted—pp. 27-28 and 31-32—for the stewardess’ report of Stahr’s conversation with the pilot and the closingdescription of the plane landing at Glendale. The report of Stahr’s lecture to the pilot about decision-making, the analysis of Stahr’s Daedalian qualities, and the description of the landing were supplied in this typescript. The presentation of Stahr as a man who has flown high to achieve an overview of life is one of the most delicate passages in the novel, a quintessential Fitzgerald passage in which he brilliantly suggests complex ideas. It is instructive to consider a discarded version of this passage.

When he came down out of the sky he saw the Glendale airport below him, bright as mischief, but awfully warm. The moon of California was straight ahead over the Pacific by the low lying lands of the Long Beach Naval Reserves. Further down, there was Huntington Park, and on the right, the great mutual blur of Santa Monica. Stahr loved these lights, each cluster. Stahr felt no apology for them. Stahr felt that he had made all this—or remade it—and all the clusters that he saw beneath him. All the clusters of lights were something he had arranged like a trouble-shooter on an electric job.

“This light here,” he said, “I will make it brighter. This cluster here.

“And this I shall black-out, and this I will lay my hand on, reluctantly, cruelly, definitely, and squeeze and squeeze, and something dark, something I don’t know—something I may have left behind me in the dark. But these lights, this brightness, these clusters of human hope, of wild desire—I shall take these lights in my fingers. I shall make them bright, and whether they shine or not, it is these fingers that they shall succeed or fail.”

The great plane lowered, arched down a truncated sweep into the Glendale airport. It was always very exciting to get there.

Although the writing is superb, the tone is not right; Stahr seems megalomaniacal, and the point about his sense of humanity is not made.

This is the latest version:

[Segment I]

He had flown up very high to see, on strong wings when he was young. And while he was up there he had looked on all the kingdoms, with the kind of eyes that can stare straight into the sun. Beating his wings tenaciously—finally frantically—and keeping on beating them he had stayed up there longer than most of us, and then, remembering all he had seen from his great height of how things were, he had settled gradually to earth.

The motors were off and all our five senses began to readjust themselves for landing. I could see a line of lights for the Long Beach Naval Station ahead and to the left, and on the right a twinkling blur for Santa Monica. The California moon was out, huge and orange over the Pacific. However I happened to feel about these things—and they were home after all—I know that Stahr must have felt much more. These were the things I had first opened my eyes on, like the sheep on the back lot of the old Laemmle studio; but this was where Stahr had come to earth after that extraordinary illuminating flight where he saw which way we were going, and how we looked doing it, and how much of it mattered. You could say that this was where an accidental wind blew him but I don’t think so. I would rather think that in a “long shot” he saw a new way of measuring our jerky hopes and graceful rogueries and awkward sorrows, and that he came here from choice to be with us to the end. Like the plane coming down into the Glendale airport, into the warm darkness.

Ribbon copy (B) was an expansion of itself—with new typed pages interpolated—because its carbon copy (C) is 25 pages. The carbon copy has revisions in another hand, as well as shorthand notes and shorthand inserts. In the early stages of work Fitzgerald tried to dictate revisions to his secretary, a method he had acquired at studio script conferences.

The next level of revision for Chapter 1 is the typescript draft designated 2, which survives in a heavily revised ribbon copy (D) and an untouched carbon copy (E). After Fitzgerald revised the ribbon copy, he altered the draft number from 2 to v. 3—indicating that this second working typescript was to be retyped as version 3. Fitzgerald’s revisions in the typescripts for Chapter 1 are all in the nature of stylistic polishing; there is no new action.

The third typescript draft exists in three copies: an unrevised ribbon copy (F), an unrevised carbon copy (G), and a revised carbon copy (H) which Fitzgerald indicated was to be retyped as v.4.

The fourth typescript draft survives in only a revised ribbon copy(I). Although it is the latest draft, Fitzgerald did not regard it as the final draft. At the head of the first page he wrote: “Rewrite from mood. Has become stilted with rewriting Don’t look rewrite from mood”. The same note was made on the carbon copy (G) of the third typescript.

With the first chapter belongs a trial opening of four holograph pages (J) and three typed pages (K), describing the take-off from Newark airport and listing the passengers.

[Segment K]

CHAPTER I

—It was still “roses, roses all the way” down to 1935—for me anyhow. For I had enough good looks and more than that amount of youth, and there was abundant money. It was fun to be discreetly superior on the coast because I went to Smith College in Northhampton, Mass., and to be rather mysteriously awesome in the East because of father’s potential ability to make anyone a picture star. Of course this was nonsense, and I never encouraged such an idea among my friends. But I’ve been enough around Jewish people—and Jewish people are continental whether they think so or not—to be a realist about such matters.

Anyhow it was mostly roses, roses—especially that June with exams over, getting on the Douglass Mainliner to fly back home. Father had written that everything was better and better and enclosed me a check for—but I won’t make you hate me by saying how much. I had bought a regular trousseau for myself and gifts for everybody I liked except Stahr. It was kind of unimaginable getting anything for him. A little like buying a present for Santa Claus. Oh, I admit I looked all over Brooks Brothers for something but I simply couldn’t do it in the end. Nothing was quite right. Don’t laugh—or there won’t be any more story.

The plane left Newark airport at 4:30 and by five we had all stuffed our chewing gum furtively into the little ash holders—and then there was nothing much except getting used to the motors and to the usual qualms, and finding out who was on board. I’d seen the list in the airport—Lee Spurgeon, Stoner, Mortimer, Fleishhacker,Gratteciel—but these might be phoney names for people I knew. I just sat for awhile—hours I guess—and wondered if anybody was liable to come into my life on this trip. I’d never been in pictures but I was very much of them—and I had an actress psychology about staring straight ahead in any new situation—until I found where I was.

My father, James Bradogue, was a self-made man, half Irish and half Pennsylvania Dutch. He was a publicity man and then an agent and then an executive and then a capitalist like now. I was born about when the “Birth of a Nation” was previewed, I guess. I know Rudolph Valentino came to my fifth birthday party. I can remember when there wasn’t any Garbo or Shearer and Crawford and I’m one of the few people who killed Desmond Taylor but you’ll never find out about that from me. We were in the picture business just like other families are in the grain business or the furniture business and I just accepted it I guess, like an angel accepts heaven or a ghost accepts his haunted house. So except for a few odd stray moments—and most of them I’m going to tell you about—it never had any magic or romance or glamor for me.

The discarded opening narrative frame in which Cecelia is introduced as telling her story to fellow-patients at a desert tuberculosis sanitarium survives in six typescript and carbon drafts (L-Q), but there is no manuscript draft. The main problem with this frame is that it sets up a narrative within a narrative. In his early notes Fitzgerald refers to the “recorder”—that is, the person who is reporting Cecelia’s narrative. Cecelia’s story was being reported by one or two outsiders: “What follows is our imperfect version of her story.” Fitzgerald abandoned this method, which is unnecessarily cumbersome—particularly since Cecelia has to document the parts of her story that she learned from other figures. Sheilah Graham thinks that Fitzgerald considered salvaging the sanitarium material as the conclusion for the novel.

[Segment P]

We two men were fascinated by that young face. A few months ago, we had made a short trip to the canyons of the Colorado as if for a last gape at life; now back at the hospital this girl’s face in the sunset, and with the fever, seemed to share some of the primordial rose tints of that “natural wonder.”

“Go on tell us,” we said. “We don’t know about such things.”

She started to cough, changed her mind—as one can.

“I don’t mind telling you. But why should our friends, the asthmas, have to hear?”

“They’re going,” we assured her.

We three waited, our heads leant back on our chairs, while a nurse marshalled a flustered little group that must have heard the remark—and edged them toward the sanitarium. The nurse cast a reproachful glance back at Cecelia as if she wanted to return and slap her—but the glance changed its mind and the nurse hurried in after her flock.

“They’re gone. Now tell us.”

Cecelia stared up at the brilliant Arizona sky. She regarded it—the blue air, which to us had once stood for hope in the morning—not with regret but rather with the cocksure confusion of those the depression caught in mid-adolescence. Now she was twenty-five.

“Anything you want to know,” she promised. “I don’t owe them any loyalty. Oh, they fly over and see me sometimes, but what do I care—I’m ruined.”

“We’re all ruined,” I said mildly.

She sat up, the Atzec figures of her dress emerging from the Navajo pattern of her blanket. The dress was thin—gone native for the sun country—and I remembered the round shining knobs of another girl’s shoulders at another time and place but here we must all stay in the shadow.

“You shouldn’t talk like that,” she assured me, “I’m ruined, but you’re just two good guys who happened to get a bug.”

“You don’t grant us any history,” we objected with senescent irony, “Nobody over forty is allowed a history.”

“I didn’t mean that. I mean you’ll get well.”

“In case we don’t, tell us the story. You still hear this stuff about him. What was he: Christ in Industry? I know boys who worked on the coast and hated his guts. Were you crazy about him? Loosen up, Cecelia. Something for a jaded palette! Think of the hospital dinner we’ll face an half an hour.”

Cecelia’s glance suspected, then rejected our existence—not ourright to live but our right to any important feeling of loss or passion or hope or high excitement. She started to talk, waited for a tickle to subside in her throat.

“He never looked at me,” she said indignantly, “And I won’t talk about him when you’re in this mood.”

She threw off the blanket and stood up, her center-parted hair falling from her wan temples, ripples from a brown dam. She was high-breasted and emaciated, still perfectly the young woman of her time. Superiority was implicit in her heel taps as she walked through the open door into the corridor of the building—our only road to wonderland. Apparently Cecelia believed in nothing at present, but it seemed she had once know another road, passed by it a long time ago.

We were sure, nevertheless, that sometime she would tell us about it—and so she did. What follows is our imperfect version of her story.

Chapter II

(Episodes 4-6)

- A Manuscript. [1-13]. “Chapter II.”

- B Revised Carbon Copy & Revised Typescript. [26] 27-29, 29½ (30-31), 32-33 [inserts A & B] 34-36, 36½, 36½A, 37-39, “CHAPTER II.” #2

- C Typescript. [26] 27-29, 31-38. “CHAPTER II.” #2 #1

- D Revised Carbon Copy. [33]—34. #2

- E Manuscript & Revised Carbon Copy. [1] 1½, 2, 2½, 3, 3½, “Chapter II.” #v. 2

- F Revised Typescript & Manuscript. [1] 2-9. “CHAPTER II.” #2

- G Revised Typescript. 25-31. “CHAPTER II.” #v.2

- H Manuscript & Revised Typescript. 1-5. “Chapter II.” #2 [#3.]

- I Revised Typescript. [25] 26-29. “CHAPTER II.” #3

- J Manuscript & Revised Typescript. 1-7 [8-18].

- K Revised Typescript. 30-33. #3

- L Revised Carbon Copy. [26] 27-33, “CHAPTER II.” #2

- M Revised Typescript. 1-4, 6, 5, 6, 7-9. “CHAPTER II.” #4/ /#v. 1

- N Carbon Copy. [25]-30. “CHAPTER II.” #4. 3 copies

- O Revised Carbon Copy. 29-36, [insert], 37-38

- P Carbon Copy. [1-4].

- Q Manuscript, g-k.

- R Manuscript. 1-12.

- S Typescript. 20, 33-36, [37]

- T Manuscript. [1-17]. “Chap II (Part III).”

- U Typescript. 1-5

- V Revised Carbon Copy. 43

- W Manuscript. 1-20. “Episodes 4 and Five”; “Episode 6 (7 is out).” Latest Holograph.

- X Revised Carbon Copy. 1-6. “Episodes 4 and 5.”

- Y Revised Typescript. 1-6. “Episodes 4 and 5.” Latest Typescript.

- Z Carbon Copy. 1-3. “Episode 6.”

- AA Revised Typescript. 1-3. “Episode 6.” Latest Typescript.

- Outline

- B 4. Johnny Swanson—Marcus leaving—Brady July 28th

5. The Earthquake

6. The Back lot

The earliest holograph draft for the opening of Chapter 2 (episodes 4-6) appears to be thirteen fragmentary unnumbered pages (A) describing the studio at night and the earthquake. In this material Cecelia addresses an aside to “my gallant gentlemen,” indicating that at this point Fitzgerald still intended to use the sanitarium frame. The account of Stahr’s first sight of Thalia (Kathleen) is missing, but after Stahr falls into a pool of water Cecelia reports that “She came up to him, right like a tart, I suppose and wiped him off.” Although Cecelia does justice to Thalia’s beauty, her application of terms like “tart” and “trollop” to Thalia may indicate that Fitzgerald was preparing the reader for the information that Thalia has had an active sexual history. Or perhaps these terms were only meant to convey Cecelia’s resentment of Thalia.

Thalia was the muse of comedy and bucolic poetry. Sheilah Graham reports in The Real F. Scott Fitzgerald (p. 180) that Fitzgerald changed the name from Thalia to Kathleen after she told him about a London showgirl named Thalia who burned to death when her hair caught fire. The character is not named in the later drafts for this chapter.

At least one layer of draft for this section of the novel has been lost, for there is no complete first typescript. The earliest surviving typescript is an incomplete fifteen-page draft (B) assembled from ribbon copy pages of one typescript and carbon pages from another typescript. It is heavily revised by Fitzgerald and also in shorthand. Three of the pages are designated “2”—indicating that this draft conflates two levels of typescript. The unrevised ribbon copy (C) numbered [26]-38 was partly copied from the conflated draft (B) and is itself a conflation; it is identified on seven pages as “2,” but the last two pages are marked “1”—indicating that these pages were salvaged from the missing first typescript. Ribbon copy (C) forms a complete episode—except for missing p. 30—up to Stahr’s encounter with Thalia. In this typescript Robinson introduces Stahr to his ne’er-do-well brother, Horace, who is in some kind of unspecified trouble and needs a job. Almost certainly Fitzgerald was planting Horace Robinson for later use in the novel, a plan which was soon abandoned. Since both of these drafts begin at page number 26 work on them followed completion of the 25-page latest typescript for Chapter 1. At this early stage of composition Fitzgerald was still trying to finish and polish one chapter at a time—instead of drafting the whole novel—in order to have 15,000 words of material to show Collier’s.

Stahr’s first name is given as “Munroe” in these early drafts; but it is uncertain if a simple spelling problem was involved. Fitzgerald’s notes indicate that he originally considered giving Stahr the first name “Irving”—which would have made the identificationwith Irving Thalberg too strong. Fitzgerald then tried the name “Milton” before settling on Monroe. The name “Stahr” requires no explication, but it is perhaps worth noting that the slogan of MGM in the thirties was “More Stars Than There Are in Heaven.”

There is a two-page carbon copy (D) describing Thalia at the moment Stahr helps rescue her in the flood, marked “OLD CHAP II (Restaurant Scene”—perhaps an indication that Fitzgerald planned to use it elsewhere in the novel.

[Segment D]

(it was hard to say.) She looked, for a split second, like an out-and-out adventuress (—the sort of girl that boys see in the front row of the chorus once when they are young—and who afterwards subconsciously influences their entire love life. As I say, she was that way, for a split second—) as “common” as they come, ready for anything male—a wench, a free booter, an outsider.

And then Stahr saw that she was a raving beauty, (hapless and helpless at the moment, no doubt, but even so, giving the impression of living halfway between heaven and earth—infinitely piteous.) Something about her made one catch one’s breath, choke back any last thought of (your) ones own self, (your own well being—and “knocked your eye out,” as they say.

Not the professional kind of beauty either. I could forgive that in retrospect.) She was not the kind that chokes up the areas of dinner parties in our little town on the coast giving no other woman breathing room, but rather like Constance Talmadge was once—from all reports. I can’t confirm the reports, because all I remember about Constance when I was a little girl was just her laughter, and then her being ready to laugh, and then bang! more laughter.

Perhaps that’s beauty—perhaps that’s what Stahr saw in his Thalia then: laughter, and then doubt as to whether it was time to laugh, and then, always waiting around the corner—more laughter.

I hate to intrude myself into the picture, even for contrast, but I’m not like that. I wait till I’m amused. Even if I’m trying to please someone. But Thalia was all laughter. Her face just set that way. Even if she said nothing more important than “What! Darling?” with her eyes all tinkling at the edges.

(You were shocked at her beauty. Let me admit that and get it over with. It was enough to keep one awake at night.)

It was there too when she moved. Everybody has had the excitement of seeing an apparent beauty from afar; and then, after a moment, as that same face grew mobile—watching the beauty disappear second by second, as if a lovely statue had begun to walk with the meager joints of a paper doll. There was nothing of that in Thalia.

She came right up to him, took his handkerchief out of his breastpocket and wiped off his hands, with that laughter, I suppose.

(I can hear it now! Thinking of it makes me remember the time when I lost my boy. When he played the piano over and over to that girl Reina, and I realized at last that I wasn’t wanted. That piano in a little New England roadhouse near Smith, playing Jerome Kern over and over. The keys felling like leaves; his hands and then her hands over them splayed as she showed him a black chord. I was a freshman then.)

Another holograph chapter opening of six pages (with one page of carbon) is designated “v2” on the first page (E). It goes up to Stahr’s departure from his office for the flood site and introduces Robinson. There is no typescript for this material.

The next stage of the opening of Chapter 2 is nine pages of ribbon copy, carbon copy, and holograph marked “V.2” (F). Here Robinson asks Stahr to hire his brother, and the women are rescued from the head of Vishnu. Stahr is struck by the beauty of one of the women, but the encounter is not developed. The segment ends with Stahr leaving to change his wet clothes. Related to this segment is a seven-page ribbon typescript (G) marked “2” that Fitzgerald stripped: “Stet whats marked only. Destroy the rest.” It is longer than segment (F) and closes with an analysis of Stahr’s prestige with his employees and a description of his office.

The change from Vishnu to Siva for the prop from which Kathleen is rescued indicates the pains Fitzgerald took with minor details. Vishnu is the Hindu god regarded by Vishnavas as the supreme diety. Siva is the Hindu diety representing the principle of destruction as well as the reproductive or restoring power; Siva is also the great ascetic, the worker of miracles. It is appropriate forStahr and Kathleen to be brought together through the agency of Siva, for Kathleen embodies the elements of both Stahr’s restoration to life and his destruction.

The earliest identifiable segment of the next draft is a five-page holograph and revised ribbon copy description of the studio at night, the earthquake, and the rescue of the women (H). The two pages of typescript in (H) were originally marked “2” but changed to “3.” This opening sequence was retyped and revised as “3” (I). By now Horace Robinson had been removed.

The third-draft typescript opening is continued by eighteen pages of holograph and revised ribbon copy (J). Here the first encounter between Stahr and Thalia is expanded by his insistence on getting her dry clothing. He takes her to the wardrobe department and talks about his work: “But when you grow older you’ll find that anywhere anything much goes on it is always very quiet.” Stahr returns to his office and phones Cecelia, who provides two versions of the call—one in which Stahr asks her to have a cup of tea with him, and another in which Thalia was apparently in Stahr’s office ( “Of course I had no idea who was there.”). Related to draft (J) are a four-page revised typescript (K) of Stahr’s conversation with Thalia, and a revised carbon copy of the opening of the chapter (L).

The fourth typescript draft survives in two forms: a ten-page revised ribbon copy (M) salvaged from “v. 1” with two pages marked “4,” and three copies of unrevised carbons (N) of a different version “4.” These versions differ in their treatment of Stahr’s first meeting with Thalia. In (M) Stahr notices that one of the women is beautiful, but she makes no great impression on him. In (N) Cecelia analyzes Thalia’s effect on Stahr and describes her laugh.

There are also discarded scenes for Chapter 2. Revised carbon copy (O) with shorthand notes describes the flood and the meeting between Stahr and Thalia, in which she wipes him off. A four-page carbon copy (P) has Stahr escorting the rescued women to their car and then returning to his office.

The interesting holograph paged g-k (Q) reports the conversation between Stahr and Thalia in the commissary, where he takes her after helping to rescue her. Thalia checks the soaked contents of her purse and discovers that her tickets for a track meet have been lost, which triggers Stahl’s thoughts about his boyhood:

[Segment Q]

It wasn’t his old talking when he said Ill make it up to you. He wasn’t sorry for her because he had no use for all he had or what he was offered. As far as amusement, he had been happier in New York when he was a kid at the knowledge that he could get into Wendts bowling joint every Thursday or could bet on Friday at Skorksi’s and if he won watch the big boys in the evening.

It was just a horrible sense of waste as he thought of all the stuff that came to him now and how little he could do to it, not even pass it out or find anyone who wanted it now a days. And this girl’s two paste boards had floated out into a sea of mud, maybe meaning all to her against an empty afternoon as it had meant to his mother that day when she had lost the tickets for the Menorah festival. It must have been that for he would always rather do things than watch other people do them. But he knew what defeated anticipation meant in human life so he said,

“Look tomorrow I’m going ect.

Except for a brief description of Stahr as a gang leader in the Bronx, nothing is provided about Stahr’s boyhood in the latest drafts of the novel. The revisions in Chapter 2 are in the direction of compactness or foreshortening. It is sufficient for Stahr to be shown functioning at the peak of his ability; background on his boyhood does not necessarily add to the characterization. For his own use, however, Fitzgerald wrote a background sketch about Stahr—in which he obviously used the facts of Thalberg’s career. Fitzgerald needed to know all about his hero, but it was not obligatory for the reader to have the information. (See Sheilah Graham’s 11 January 1941 letter to Maxwell Perkins in Chapter 6 below.)

Stahr will have to be born in New York or Brooklyn or Newark. Remember the story in which Carl Laemele kept making long distance calls asking about this and that fact and getting answers from a voice who described himself vagule as the assistant and describing troubles that he had had with perforationss in certain films that had been faulty and how he had to go to Selig in Philadelphia and give him the right to make the prints in order to get him to correct thefaulty perforation in the films caused by an imperfect jointure of the work of several cameras. Look up that incident in “A million and one nights.”

Also this assistant had settled several difficult negotiations with stage actors and actresses who were wanted on the coast. Though the assistant described various of these endeavors to the Eastern manager, who had really been sick or on a bust or occupied in some affairs of his own during this time; Laemele after a month became rather puzzled about the situation and said very much as follows:

“Say, I have been spending anywhere from twenty to a hundred dollars on thse calls and there have been plenty of them and I never manage to find that fellow in. He must be awfully busy running around and, by the way, who are you? You say you’re an assistant. Who are you?”

Whereupon Stahr answers:

“Well, to tell you the truth, Mr. Laemele, I’m the office boy.”

Whereupon, Laemele swore and when he calmed down a little, he said: “No you’re not, you’re not the office boy, you’re the Eastern Manager.”

Fitzgerald’s early biographical sketch for Thalia shows that he originally conceived her as having a much less glamorous background than he invented for Kathleen, although Thalia’s domestic situation was extremely complex:

THALIA was born in 1908 in Newfoundland.

She was married in ’29 to a rich man who came to Newfoundland as a tourist and loved her. She came of very humble parents, father was captain of a fishing snack and it was a run-away marriage. She married this wealthy man who had a place there. They had an awful time about their marriage because he was married. She had to live with him a year before he could divorce his wife and marry her.

One of the children of the first marriage died. It was blamed on her because if the divorce had not occurred and she hadn’t appeared, it would not have happened. Her husband went all to pieces, lost all his money and she is still taking care of him in a vague way and he is perhaps in a sanitarium in the East and perhaps dead.

She came to California as a companion of the wife (KIKI) who isdivorced and who leans on her altogether and at times is very grateful to her and sometimes turns on her for breaking up her home. She has become a great friend of this wife—both of whom love this man—and has stepped in and helped by giving up her own plans and what money there was. The wife is kind of a broken neurotic who has dabbled in dope and Thalia is haunted by the idea that she has broken up this home and doesn’t know what her position is—she did it for love, etc., but she did break up this home, she feels.

The first wife has a little girl left from the marriage. She takes care of this woman part of the time and also does part time work in her mornings, but has never considered the studios and when she meets Stahr it is absolutely unimportunate.

Her position in the home has gradually drifted into that of an upper servant because she unfortunately was too generous in a moment of feeling of atonement. She has been having an affair intermittant of which she is half ashamed, with the character whom I have called Robinson the cutter who is in his: (and this is very important) professional life an extraordinarily interesting and subtle character on the idea of Sergeant Johnson in the army or that cutter at United Artists whom I so admired or any other person of the type of trouble shooter or film technician—and I want to contrast this sharply with his utter conventionality and acceptance of banalities in the face of what might be called the cultural urban world. Women can twist him around their little finger. He might be able to unravel the most twisted skein of wires in a blinding snowstorm on top of a sixty foot telephone pole in the dark with no more tools than an imperfect pair of pliers made out of the nails of his boots. but faced with the situation which the most ignorant and useless person would handle with urbanity he would seem helpless and gauky—so much so as to give the impression of being a Babbitt or of being a stupid, gawky, inept fellow.

This contrast at some point in the story is recognized by Stahr who must at all points, when possible, be pointed up as a man who sees below the surface into reality.

Her attitude towards this man has been that even in the niceties of love-making she has had to be his master and his deep gratitude to her is allied to his love for her though throughout the story he always feels that she is inevitably the superior person. Stahr at some pointpoints it out to her that this is nonsense and I want to show here something different in mens’ and women’s points of view: particularly that women are prone to cling to an advantage or rather have less human generosity in points of character than men have, or do I mean a less wide point of view?

Thalia’s relationship with Robinson was to have motivated him to join Brady’s conspiracy against Stahr in the original plot of the novel. At one stage Fitzgerald considered that Robinson would be the man selected to murder Stahr or that Stahr would plan Robinson’s murder:

The man chosen tentatively to put Stahr out of the way is Robinson the cutter. Must develop Robinson character so that this is possible, that is Robinson now has 3 aspects. His top possibility as a sort of Sergeant Johnson character as planned. His relation with the world which is conventional and rather stereotyped and trite and this new element in which it would be possible for him to be so corrupted by circumstance as to be drawn into such a matter and used by Bradogue. To do this it is practically necessary that there must be from the beginning some flaw in Robinson in spite of his courage, his resourcefulness, his technical expertness and the Sergeant Johnson virtues I intend to give him. Some secret flaw—perhaps something sexual. It might be possible, but if I do that, then he could have had no relation with Thalia who certainly would not have accepted a bad lover. Perhaps he would have some flaw, not sexual—not unmanly—in any case have no special idea at present, and this must be invented. In any case, his having loved Thalia would make him a very natural tool for Bradogue to use in playing on his natural jealousy of Stahr.

Compactness or dramatic impact also dictated Fitzgerald’s decision to hone Stahr’s first encounter with Thalia to a glimpse. In the latest draft it is literally love at first sight for Stahr, although his reaction is delayed.

Chapter 2 underwent a steady process of reduction through the draft stages as Fitzgerald sharpened the focus and cut out expository action. Two linked scenes at the end of the chapter were delted: the twelve-page holograph quarrel between Wylie White and Stahr (R), and the seventeen-page holograph section in which Stahr hears Brady plotting against him (T)—both of which also survive in typescripts (S and U) separated from the working drafts.

[Segment S]

His night secretary stood in a listening attitude in front of the closed door of the main office.

“There’s someone inside, Mr. Stahr,” she said in alarm, “I went to the wash-room and when I came back someone had gotten in and locked the door from the inside. I didn’t know quite what to do—I think from his voice it’s Mr. White.”

Stahr tried the door.

“Wylie?” he called.

After a moment a blurred voice answered him.

“Just second. I’m engaged on the phone.”

“Let me in, you dope!” Stahr ordered impatiently. The receiver clicked and Wylie came to the door. He was deeply, vitally drunk.

“I’ve been putting in calls,” he said, “—in your name.”

“Who to?” demanded Stahr.

“Everybody—The department of Forestry in Washington, the newspapers, the commissary—I ordered you twisted fish and a cat’s handle-bar and they keep calling back about it. And I called the Navy in San Diego and ordered a cruiser to take you down the Mississippi—to spot locations for Tom Sawyer. I told the publicity department all our stars were killed in the earthquake and I told ’em to play it up big—”

Stahr opened the door and spoke briefly to the secretary.

“Trace Mr. White’s calls on my private wire and see what he’s done and fix it up.”

He closed the door sharply, went over to White and smashed him in the face. Wylie staggered against the table. He outweighed Stahr by forty pounds and presently he got his balance and took a step forward.

“You God damned drunk,” cried Stahr. “I told you to stay sober. Get off this lot and if I ever see you again I’ll ruin you.”

Wylie White’s hand fell heavily on Stahr’s shoulder. Stahr shook it off and hit him again in the face.

“I’m through with you,” he raged, “I pulled you through D.T.’s and gave you another chance—”

Wylie’s arm tensed to throw a punch that would have floored Stahr but the second blow or the words that went with it seemed to sober him. He sat down on a great couch sinking his face in his hands.

“Get out!” cried Stahr, his hand fumbling on his desk for something to hurl. Then suddenly his temper broke too, and he said “Hell’s bells,” and sat down behind his desk looking at his bleeding knuckles.

“What was the idea?” he demanded. A sudden kindliness, a quick ray as spontaneous as his outbreak, came into his face. The short flash of a smile showed forgiveness, shame, affection.

“Oh, I just got tired hearing what a great man you are, Monroe,” said Wylie coldly, “Somebody told me once too often. Because they’re wrong. Two years ago most of the boys around here would have died for you, but times have changed and you don’t read the signs. You’re doing a costume part and you don’t know it—the brilliant capitalist of the twenties. But these secretaries and typists that have been living on hay since ’29—they don’t see themselves as Joan Crawford characters anymore. They want to eat.”

Stahr was silent—it was as good a time as any to pump Wylie.

“You can suppress them easy enough or replace them but you better keep you hands off the writers.”

“You promised me you were through with politics,” Stahr reminded him. He took a suit from a wardrobe closet, and began to shed his wet clothes.

“If you’d give me a producer contract I’d be out of it,” said Wylie. “As a writer I’ve got to be on one side or another—(and) I can’t be a god damn fink.”

“I told you that when you’d been sober two years I’d let you produce.”

“Out here two years is a lifetime.”

“Tonight isn’t going to help,” said Stahr, “And I’ll be damned if you can come up here and blame me for the whole American system. I’ve fought Bradogue and his bastards till we’re just about speaking and that’s all. I’ve threatened to quit so often that I laugh when I say it. And now you boys turn on me. Why, I made you. Most of you are once-a-week writers that couldn’t earn a good living in the east—maybe thirty a week on a newspaper. And we pay you enough for chauffeurs and swimming pools.”

He was tieing his tie in the mirror.

“—and you kid yourself into thinking you’re horny handed workers. Some little tit still wet behind the ears called me a fascist the other day.”

“You’re done, Monroe,” said Wylie stubbornly, “I like you because I’m a romantic but the times have passed you by. You don’t know what’s happening.”

“When I was sixteen, Wylie, during the war, I was an office monkey on the New York Call. I was there during the suppression and the raids and all us boys read the Communist Manifesto and swore by it.”

“I guess it didn’t sink in.”

“In a way—but I’m not one of these natural believers always asking where the church is. Or the cathouse or the saloon either. Thinking’s a lot harder than believing but it’s more fun too. And it occurred to me that I was a better man than most of those fellows. If they’d been planning to make me a big shot I might have played along, but there wasn’t any future.”

“That was a bad guess, Monroe.”

“Don’t be so sure. I saw this world was going to function a little longer anyhow. I couldn’t breath with those people—nine-tenths of them ready to sell out for a nickle. More dirty politics than there is in a studio, and all covered up with holy talk, and not a laugh in a carload. I became a Jew again. I swear I did. And I was a good one till Minna died. A perfectly happy good Jew.”

(There was a silence for a moment as they both glanced at her picture on his desk.

“I met a girl who reminded me of her tonight,” said Stahr.

“Did you—where?”

“Out on the back lot. Do you remember how Minna smiled—as if she was just ready for laughter—” He broke off. “This woman wanted to laugh tonight—in just the same way—and would have if I’d looked at her and it would have been just like Minna. So I didn’t.”)

Wylie took advantage of this self-absorption to ask.

“Say have you got a drink?”

“Yes, but not for you. Your eyes are only just beginning to look human. I want to know why you’re beginning to talk like a Red again. You’re drifting back.”

“No I’m not,” said Wylie, “They wouldn’t take me. I’m on the blacklist. They only want to use me.”

“You going to let them?”

“Why not? I’ve got a conscience, Monroe. I was born a Catholic and a Catholic conscience takes a long time to kill. I couldn’t fight them, I couldn’t come out against them. They’re pretty awful but they’re right. You can make your smart speeches about how lousy they are and not one out of ten is anything but a holy Joe or a poor kid gone sour. But when you finished it’s you who have to say ’So what?’ to yourself.”

“I don’t say ’So what?’ to myself,” said Stahr sharply, “I told you in the plane coming out here that you were soft stuff—all of you. A bunch of soft mush letting yourselves be pushed around by boys that are going to get something out of it.”

“Sure—I know. They’d liquidate us first of all. But I can’t change myself—I’ve tried and I can’t. My heart and my good sense, are with the—the dispossessed. If they eat me up then I’m just the husband of a black widow spider. That’s my hard luck.”

Stahr’s mind was not on Wylie’s immediate words. He needed a man, an intellectual, someone of force, heart, liberal opinions and popularity to split the movement among the writers. He had counted until this moment on Wylie White and now he was full of doubt both as to White’s stability in the matter of drink and as to whether money was the coin to buy him with. So long as Wylie went on bats that was sufficient grounds for not making him a producer—though in fact Stahr kept his assistant producers close under his eyes so that they more nearly fulfilled the functions of supervisors, their former and less impressive title. But it was as a writer that he could best use Wylie.

The dictograph buzzed at his elbow; he switched it on.

“Mr. Stahr, are you taking calls?”

“Who is it?”

“Well, there’s half a dozen. Joe Robinson left word that everything’s all right And’ then Mr. Bradogue.”

“I’ll get him on the inter-office.”

He pressed another button.

I was still on the couch in father’s office. The doctor had been up to take a stitch in my hand—I was the only victim on the lot—and the drug he gave me made me doze for an hour. Father was in and out; he happened to be out when Stahr called.

“Come on over here and take charge of your friend, Wylie,” Stahr said, “You can keep him out of the Clover Club and the clip-joints. He’s on a college boy bust.”

I did not know that at this point Wylie White got up quickly and said: “I’m going, Monroe. I don’t want her to see me with this eye—you did it, you bastard. It’s turning blue.”

I saw Wylie though—from a distance out in the hall, though he didn’t know it. I was excited about going to see Stahr but I suspected it would be highly impersonal.

“Wylie’s gone,” he said, “There was something the matter with his face and he didn’t want you to see it. What

[Segment U]

That would have been all if I hadn’t picked up the phone to call father. Then it transpired that the water mains had not suffered the only damage that night—for instead of talking to father I was suddenly listening to a conversation between him and someone on his private wire to New York.

“…the whole back lot is a shambles,” father’s voice said, “My daughter was almost killed …”

I laughed and signalled to Stahr who picked up an extension and listened in with me.

“… No, she’s fine now. She went home by herself,” said father. “The situation is the same. We can’t do with him and we can’t do without him.”

“Why can’t you?” said the voice. “If you can’t find a competent executive out there we’ve got young men in our office that could learn the set-up in six months.”

“We can find business men,” said my father, “—too many. Andwe can find production men. But business men who can make pictures don’t grow on trees.”

I looked at Stahr somewhat aghast. His shoulders were shaking in his effort not to laugh aloud.

“I don’t know what to think, Billy,” said the voice, “One month we hear he’s a wonder man and the next month that he’s an extravagant idealist. This isn’t 1927. Money’s hard to come by and if we’re letting millions slip away on these masterpieces he’s no man for us.”

“I watch him like a cat,” father said, “Whatever I don’t like I throw in a monkey wrench.” He paused, “Anyhow I don’t think we have to worry for so long. I’m in touch with his doctor and he’s shot to pieces. Let him work himself sick, then ship him off on a world cruise. We can still use him—his name will still mean a lot. It gets more work out of people if they think they’re doing it for him.”

For a minute I had been holding the receiver away from me like a snake’s head. Now I hung up. Stahr was still listening but the smile was gone. After a moment he hung up too, and taking a ring off his finger, exactly like the one he had given me, began playing with it.

“Celia,” he said thoughtfully, “When I meet Jew-haters I wonder if they feel about us like I do about the Irish.”

I looked at him rather fearfully, I guess. I was rather glad at being only half Irish.

“Your father knows who built this studio out of nothing; he knows I could take over any studio in Hollywood tomorrow and this would be just a gutted factory. But treachery is something he loves more than money. He’s more devious than any Jew out here. Maybe that’s why they like him in Wall Street.”

“Are you really sick?” I asked.

“Of course not,” he said scornfully.

“Father’s a pretty mean man,” I said, after a minute, “I’ve never been able to love him—even as a little girl.”

“Oh, you oughtn’t to say that.” He was a little shocked, “He’s your father.”

“He’s your partner, and you certainly must loathe him.”

“I don’t loathe him,” he assured me, almost with surprise, “You don’t hate a man you can see through like glass. All that talk about throwing monkey-wrenches! He’s never wrecked a single plan I caredabout—sometimes I send him dead horses to kill. Why if he got out I’d miss him—in the grapevine he takes the raps for half my mistakes. If something goes wrong they say that’s Billy Bradogue interfering with Monroe. That’s the advantage of a reputation, Celia—the truth is I make most of the mistakes around here—but I’m a man who’s easier to believe in.”

He was smiling again.

“You’re a good man, Monroe.”

“Oh no,” he said, “I’m too smart to get into mischief and I’m interested in people—I’ve collected a lot of them and try to take care of the good ones. But there’s no such thing as a good man in big business.”

He put his ring back in place and got up.

“Don’t think this disturbed me. Two years ago Billy put a wire in my office downstairs and when I found he knew some things he oughtn’t to know I got Joe Robinson on the trail. Then I tapped Billy’s wires and we had some fun but it took too much time so I told him about it.”

He looked at me closely.

“Just forget that about my health, will you, Celia—my doctor’s a rat.”

We went out together. It was long after midnight and the whole place seemed deserted except for two or three chauffeurs down by the commissary. I had never before heard my father speak of Stahr without respect and admiration and now I hated him for his wish that Stahr would die. Father liked to tell the story about when Stahr was an office boy in the New York offices of Films Par Excellence. Old Menges had come out to set up a West coast unit, leaving a general manager and one of the vice-presidents in charge in the East. He was getting regular communications from the manager and things were apparently going all right. Then he discovered that the Vice President had been in Florida three months and he telephoned the general manager. The first thing he heard was that the general manager had been taken sick the day he left.

“Well, who’ve I been communicating with?” he asked, “Who’s been signing the letters? Who’s been running things? Who is this I’m talking to now?”

“This is your office boy, Mr. Menges, this is Monroe Stahr.”

Father’s story was that Menges made him general manager on the spot. Anyhow he was out here at twenty-one running the old combine lot. Three years later he was already the “production genius” and Hollywood hero number one, though nobody out of California knew his name.

As we walked toward the new commissary I thought of some questions I wanted to ask Stahr. I was taking sociology that year.

“What are the general working conditions in the studio?” I asked, pretentiously.

“About average,” he said rather surprised, “We don’t run a sweat shop but we haven’t got around to employees swimming pools.”

“Wylie White says the writers work in little cubicles.”

He laughed.

“The poor horny-handed writers,” he said, Starving for sunshine and air. Well, most of the playwrights from the East work at home. The smart boys get to be producers or directors and have a suite. The others don’t work too hard unless they’re in conference in some producer’s office. They’re not really writers—they’re well paid secretaries.”

“They’d like that.”

“Well, it’s true. They’re like children. You can’t trust them so I have one work behind another on an idea—sometimes half a dozen working on the same script and not knowing about the others.”

“You rate them low.”

He nodded absently.

“Not when they write books or plays. But out here—”

He was putting me into my car and suddenly he clutched the doorhandle and fainted dead away on the pavement outside the commissary. Some chauffeurs rushed up, we threw water in his face and got him sitting up. In a minute he was all right again and concerned with how many people had seen him go down. He took father’s chauffeur aside and spoke to him quickly, then he got in his own car. He wouldn’t even let me ride home with home.

I knew then that he was probably going to die and I felt terribly sorry.

A single page of revised carbon copy (T) describes Thalia.

At this point in the ontogeny of Chapter 2 Fitzgerald wrote afresh twenty-page holograph draft (W) for episodes 4, 5, and 6—noting that “7 is out.” But Fitzgerald did not head this material as Chapter 2, for at this stage he had shifted to the procedure of working his way through the episodes of his outline. The deleted episode 7 cannot be identified with certainty, but it was probably the telephone episode(s) printed above. Although it is a strong scene and prepares for the power struggle between Stahr and Brady, Fitzgerald may have felt that it tells too much too early by informing the reader that Stahr is a dying man. Holograph draft (W) became the latest version. It closes with a heroic view of Stahr, comparing him to Napoleon. Before writing the novel Fitzgerald read Froude’s Caesar.

Segment (W) was typed in two parts: episodes 4 and 5 (six pages) and episode 6 (three pages). Both the ribbon copy (Y) and the carbon copy (X) for episodes 4 and 5 were revised, with the ribbon serving as the latest draft. The three-page ribbon copy (AA) for episode 6 was revised, but the carbon copy (Z) was not.

In rewriting Chapter 2 Fitzgerald reduced its size by half—removing Horace Robinson, trimming the first encounter between Stahr and Thalia to a glimpse, and cutting out all the post-flood material between Stahr and Cecelia. The purpose of this process was to condense an expository chapter into a tight, dramatic chapter.

Episode 7

- A Manuscript. [1]-12. “Episode 8”

- B Revised Carbon Copy. 1-6. “Episode 8 [ 7”

- C Revised Typescript. 1-5. “Episode 8 [ 7” Latest Typescript

- Outline

- C 7. The Camera man. July 29th

Stahr’s work and health. From something she wrote.

Beginning with episode 7 (the opening of Wilson’s Chapter 3), Fitzgerald worked rapidly, with little rewriting. It is clear that he had decided to finish a working draft of the whole novel—which hewould then revise and restructure. There were at least two reasons for the change in procedure: Fitzgerald needed a complete draft in order to negotiate an advance from Scribners; and he had more plot than he could really accomodate in the projected 50,000-word limit; so he was proportioning the episodes by writing them.

Episode 7 was originally marked episode 8, but is redesignated 7 on the typescript and corresponds to the note for episode 7 in Fitzgerald’s outline, as Cecelia describes Stahr’s working day, assembling the data from several sources. Fitzgerald prepared a log of Stahr’s day as a guide for describing it, but some of the material in the log does not appear in Fitzgerald’s account.

C-D

(Stahr’s Day)

|

| Stahr and News about Back lot Morgan’s Fly |

)7 | KEEP FOR TIME SCHEDULE |

| 11-11.30 | Boxley Garcia going blind. Should try to call Mrs… |

| Writing |

| 11.30-12.00 | Barrymore sick and breaking down. He’ll play it if we have to change the script and put the hero in an iron lung Find out about occulist | (8) | acting |

| 12.00-12.30 | Tough Conference inc. Jackie on the roof. Takes the gloom out of a picture and gives it style. The scram business. No Trace of girl An agent |

| Planning |

| 12.30-1.00 |

| (9) |

|

| 1.00-1.30 | COMMISSARY—Hunch about Garcia | (10) | Policy |

| 1.30-2.00 |

|

|

|

| 2.00-2.30 | Musa Dagh—Consul Details about women |

| Policy |

| 2.30-3.00 |

|

|

|

| 3.00-3.30 | RUSHES | (11) | Cutting |

| 3.30-4.00 | Finds out it’s Smith |

|

|

| 4.00-4.30 | Process Stuff on Stage ??? |

| Acting |

| 4.30-5.00 | Happy Ending with Brady The Occulist calls |

| Policy

|

| 5.00-5.30 | The Marquands The Phone Call |

| Writing |

| 5.30-6.00 | Avoiding someone Leading actresses for Long Beach |

|

Extra |

| 6.00-6.30 | Problem of Russia. Symbolic. Fatigue |

| Writing |

| 6.30-7.30 | More rushes. Well earned rest. Dubbing room |

| Cutting |

| 7.30-7.45 | Pedro Garcia |

| Personal |

| 7.45-8.30 | Dinner |

|

|

| 9.00-00 | Starts Out missing Dubbing |

|

|

The twelve-page holograph draft (A) introduces Prince Agge to whom Stahr explains that a problem has arisen because a husband-and-wife writing team, the Marquands, have discovered that other writers are also working on their script. During this conversation with Agge Stahr makes the statement, “ ’I’m the unity.’ “ In the ribbon (C) and carbon (B) copies Fitzgerald cancelled the meeting between Stahr and Agge, replacing it with the beginning of the conference between Stahr and the English writer Boxley.

A key event in episode 7 is the announcement that the cameraman Pedro Garcia (Pete Zavras) has attempted suicide. The notes indicate that he was to play an important role at the end of the novel by warning Stahr of Brady’s plots. On page 3 of the revised typescript and carbon copy for episode 7 Miss Doolan’s report on Garcia is lined out: “ ’Yes, Mr. Stahr. I called about Pedro Garcia—he tried to kill himself in front of Warner Brothers last week. Mr. Brown says he’s going blind …I’ve got Joe Wyman—about the trousers.’ “ Fitzgerald noted in the margin, “Dots don’t properly separate ideas.” But in episode 9 Stahr refers to Garcia’s “eye-trouble, “ although no source is provided for the information. Since it is unlikely that Fitzgerald intended to omit this information, a possible explanation is that he crossed out Miss Doolan’s speech in order to revise it but neglected to do so.

Episode 8

- A Manuscript & Revised Typescript. 1-5, 4, 5-13. “Episode 9”

- B Revised Carbon Copy. 1—9. “Episode 9 [ 8”

- C Revised Typescript. 1-9 “Episode 9 [ 8.” Latest Typescript.

- Outline

- 8. First Conference

Episode 8 (originally marked episode 9) consists of 3 segments: a holograph draft with 3 revised typescript inserts (A), and the revised ribbon (C) and carbon (B) copies. The typed inserts in the holograph indicate that it conflates at least two layers of writing, as Fitzgerald inserted material from rejected episode 9. Episode 8 describes Stahr’s meetings with Boxley and the impotent actor—separated by the comic interlude of gagman Mike Van Dyke demonstrating a slapstick movie routine for Boxley. The episode ends with the opening of Stahr’s script conference with White, Broaca, Rienmund, and Rose Meloney.

Beginning with the ribbon copy for episode 8 the symbol re (possibly rl) appears on the top page of the typescript of several episodes. The meaning of this symbol is not certain, but Frances Kroll Ring, Fitzgerald’s secretary, thinks it stood for “rewrite.” If so, then it is certain that Fitzgerald regarded the latest typescripts as work that was still developing.

Rejected Episode 9

- A Manuscript. 1-7. “Episode 9”

- B Revised Carbon Copy. 1-4. “Episode 9”

- C Typescript. 1-4. “Episode 9”

Rejected episode 9—which corresponds to outline episode 8—survives in holograph, typescript, and incompletely revised carbon copy. In rejected episode 9 Stahr takes Mike Van Dyke and Prince Agge to a script conference with producer Lee Spurgeon and a husband-and-wife writing team, the Marquands. Fitzgerald’s original plan was to have Agge spend the whole day with Stahr and observe all of his meetings, thereby enabling Cecelia to cite Agge as the source for her account of Stahr’s working day.

After cancelling this episode, Fitzgerald added to episode 8 the scene of Van Dyke demonstrating a slapstick routine for Boxley. In episode 10 there is a deleted comment (probably deleted by Edmund Wilson) that Popolous’ speech reminds Agge of Van Dyke’s double talk. As was noted in a cancelled part of episode 7, the Marquands are upset because other writers are working on their assignment. Stahr bluffs them by telling them he has assigned them to another script, to which they respond by asking to be kept on the original movie. Stahr leaves Van Dyke in the script conference to insult Spurgeon as a way to placate the Marquands. At the head of the carbon copy Fitzgerald noted: “OUT Double talk doesn’t jell. Whole thing confused. Name Lee Spurgeon.” This rejected episode shows Stahr as a manipulator, rather than displaying his ability to work with writers.

[Segment C]

900 words

EPISODE 9

In front of the door of the bungalow doing nothing stood a dark saucer-eyed man.

“Hello, Monroe.”

“Hello, Mike,” said Monroe. He introduced him to the visitor, “Prince Agge, this is Mr. Van Dyke. You’ve laughed at his stuff many times. He’s the best gag-man in pictures.”

“In the world,” said the saucer-eyed man gravely, “—the funniest man in the world. How are you, Prince?”

“Mike, I can use you,” said Stahr, “I’ve got a rebellion on in Lee Spurgeon’s office and I want to keep the lid on for a day. Just gang up with me for a few minutes.”

He went ahead frowning a little and during the short walk thePrince found himself engaged in conversation with Mike Van Dyke. He answered politely without quite getting the jist of the words. Something about the commissary where Mr. Van Dyke thought he had seen the prince trying to order what sounded like twisted fish and a cat’s handlebar, though the Prince was certain he misunderstood.

He tried to explain that he had not been to the commissary but by this time they were so far into the subject that he thought it quickest to admit that he had and merely parry Mr. Van Dyke’s mistaken statements of what he had done there. Mr. Van Dyke was not so much insistent as convinced and he seemed to talk very fast.

They were inside and the Prince was introduced to Mr. Spurgeon and to Mr. and Mrs. Marquand but he was now so involved in the conversation with Mr. Van Dyke that he heard himself stammering I’m glad to meet me because he was explaining to Van Dyke that he had not seen Technigarbo in Grettacolor. Again he had misunderstood. Was his name Albert Edward Butch Arthur Agge David, Prince of Denmark. That’s my cousin, he almost said, his head reeling.

Stahr’s voice, clear and reassuring, brought him back to reality.

“That’s enough, Mike. That was ’double-talk,’ he explained to Prince Agge. It’s considered funny here in the lower brackets. Do it slow, Mike.”

Mike demonstrated politely.

“In an income at the gate this morning—” He pointed at Stahr, “—did he?”

Baffled the Dane bit again.

“What? Did he what?” Then he smiled, “I see. It is like your Gertrude Stein.”

Mike Van Dyke subsided. Prince Agge looked at the three inhabitants of the room, all sulky with what was on their minds. The little eager man and his squat wife were obviously wanting to speak up but harrassed by the presence of strangers. Spurgeon, a blonde German Jew who stood behind his desk laughing obediently for Stahr, spoke up.

“Monroe, we have several things—”

“So have I,” interrupted Stahr, suddenly serious. His tone was that of a popular young headmaster, pleasant, firm, intent. The Dane saw that it evoked a complementary mood in the listeners.

“I’ve read the work you sent over and I think Mr. and Mrs. Marquand are going to be very valuable to us. In fact I’m taking them away from you, Lee.”

He had them—all three of them. His words brought their tensity down to a plane of quiet.

“I’m sorry because I liked the scenes—especially the ones on the bus from 6 to 13 A.” He turned courteously to the woman as if he had read her handwriting through the typescript. “It was fresh and new.”

“It was my husband’s scene,” said Mrs. Marquand quickly.

“It was a fine scene.” He looked at Lee Spurgeon, “Keep it just as it is. I need the Marquands on another story—something we don’t have to get on the screen so quick.”

A short silence.

“But we like the story—” began Marquand, “It’s only that—”

“I must go,” said Stahr. His eye flickered surreptitiously at Van Dyke. “Come and see me tomorrow at noon.”

Mike Van Dyke stepped into the breech, addressing the two hesitant Marquands.

“Does Lee ever go ’Bang!—Bang!—Bang!?” he inquired maliciously, striking his palm with his clenched fist. “You know: ’And then the girl burns up bang! and then the man breaks out bang! and then the sky falls bang! And then we get Bang! Bang! Bang! If he hasn’t sold you that he hasn’t given you the old fashioned seed-corn prester m’chester.”

He had some grudge against Spurgeon and he was taking full advantage of an opportunity. Stahr had turned away, cocking back a watchful eye.

“He has a beginning too—watch for it. Once when he was a kid he looked through a fence and saw a rich girl with big dogs jumping around her. If you ever want to sell him something have a big dog in it. Have it jump on a girl.”

Stahr and the Prince were out now but as the door closed they heard the jester continuing inside, intoxicated with his ecstatic moment of power.

“Or else have a rich girl go into a stable and slap a horse on the rump—”

Out in the timid California noon Stahr stuck his hands deep in his pocket and frowned.

“Those Marquands are good people—I can’t let them go.”

“You’re putting them to another picture.”

“No—tomorrow they’ll ask to stay on this.”

“Even with other people writing it too.”

Stahr nodded.

“It’ll be all right. It’s only that Spurgeon handles writers badly. He doesn’t know which ones need a firm hand and which ones don’t. People like the Marquands would pack up and get out tomorrow. Spurgeon doesn’t know what pride is—there’s not much of it around here.”

But looking at Stahr Prince Agge was not at all sure this was true.

Episode 9

- A Manuscript & Revised Typescript. 1-19 “Episode 10 [ 9”

- B Revised Carbon Copy. 1-11 “Episode 9”

- C Revised Typescript. 1-11 “Episode 9” Latest Typescript

- Outline

- 9. Second conference and afterwards.

Episode 9 (originally marked episode 10) survives in three drafts: a holograph draft with one page of revised typescript (A), and the revised ribbon (C) and carbon (B) copies. This episode, which replaces rejected episode 9, presents a much more impressive view of Stahr in a script conference with Broaca, Rienmund, White, and Rose Meloney. The description of Rose Meloney at the end of episode 8 is repeated in episode 9; it was deleted in the second appearance, probably by Wilson. (See Sheilah Graham’s 11 January 1941 letter to Maxwell Perkins in Chapter 6 below.) Here Stahr functions brilliantly, explaining to the group how to rewrite their script. The conference is followed by a conversation between Stahr and his secretary, Miss Doolan, about tracing the girls in the flood and about Pedro Garcia’s suicide attempt. The ribbon typescript has the note “[ ] re but transfer last page to end of Episode 7”—indicatingthat Stahr’s conversation with Miss Doolan about the girl wearing the silver belt was to follow his first attempt to trace the women. The episode was to end with the words, “The conference was over.”

Wilson interpolated into the end of episode 9 a brief scene salvaged from rejected episode 10 in which Agge is with Stahr when a misconnected call from Marcus comes through to Stahr. (This scene appears on pp. 43-44 of the first edition of The Last Tycoon.) There is no compelling reason for inserting this material in episode 9, apart from showing the impression Stahr makes on the Danish Prince—who has not appeared in the novel at this point (Agge had been introduced in rejected episode 9). It is possible that Fitzgerald intended to use misconnected phone calls as a symbolic device—see the call between Brady and the New York office that Stahr hears in the cancelled portion of Chapter II. The idea was apparently dropped—or at least refined. There is a good deal of telephoning in the novel, but that is natural for Stahr.

Rejected Episode 10

- A Manuscript. 8-18, insert 18 1-3, 19. “Episode 10”

- B Carbon Copy. 1-11. “Episode 10.”

- C Carbon Copy. 1-11. “Episode 10”

A rejected first draft of episode 10—which corresponds to outline episode 9—survives in holograph (A) and two carbons (B & C). It covers Miss Doolan’s reports on the girl’s name and Garcia’s eyesight, Stahr’s script conference with Broaca and White, the mis connected call from Marcus, Miss Doolan’s second reports on the girl and Garcia, and Pops Carlson’s slapstick routine. Fitzgerald stripped one of the carbons of the slapstick material which he then incorporated in episode 9—renaming Carlson Mike Van Dyke. There is an important difference between this rejected version of the script conference and the revised version: in the rejected version Stahr is shown blundering:

[Segment C]

“And that’s no good about the child playing with the loaded revolver. It’s lousy.”

The Dane saw White and Broaca exchange a glance. Stahr saw it too.

“Well, it is,” he said, “I’m not going to waste a good morning saying why. Get something else there—I had a—”

Wylie laughed suddenly. Politely and maliciously he took a sheet from his folio and gave it to Stahr.

“Orders of the old master,” he said, “You went for it. Here’s the note.”

Stahr looked at the paper angrily.

“I had a lapse,” he said. “It’s an uncomfortable scene. What I was thinking—”

There is no comparable material in any of the latest typescripts, for Stahr is always right and has no memory lapses or errors in judgment.

Episode 10

- A Manuscript. 1-11. “Episode 11”

- B Carbon Copy. 1-7. “Episode 11 [ 10”

- C Revised Typescript. 1-7. “Episode 11 [ 10.” Latest Typescript

- Outline

- 10. Commissary and Idealism about non-profit pictures.

Rushes. Phone call, etc.