Flight and Pursuit

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

In 1918, a few days before the Armistice, Caroline Martin, of Derby, in Virginia, eloped with a trivial young lieutenant from Ohio. They were married in a town over the Maryland border and she stayed there until George Corcoran got his discharge—then they went to his home in the North.

It was a desperate, reckless marriage. After she had left her aunt's house with Corcoran, the man who had broken her heart realized that he had broken his own too; he telephoned, but Caroline had gone, and all that he could do that night was to lie awake and remember her waiting in the front yard, with the sweetness draining down into her out of the magnolia trees, out of the dark world, and remember himself arriving in his best uniform, with boots shining and with his heart full of selfishness that, from shame, turned into cruelty. Next day he learned that she had eloped with Corcoran and, as he had deserved, he had lost her.

In Sidney Lahaye's overwhelming grief, the petty reasons for his act disgusted him—the alternative of a long trip around the world or of a bachelor apartment in New York with four Harvard friends; more positively the fear of being held, of being bound. The trip—they could have taken it together. The bachelor apartment—it had resolved into its bare, cold constituent parts in a single night. Being held? Why, that was all he wanted—to be close to that freshness, to be held in those young arms forever.

He had been an egoist, brought up selfishly by a selfish mother; this was his first suffering. But like his small, wiry, handsome person, he was all knit of one piece and his reactions were not trivial. What he did he carried with him always, and he knew he had done a contemptible and stupid thing. He carried his grief around, and eventually it was good for him. But inside of him, utterly unassimilable, indigestible, remained the memory of the girl.

Meanwhile, Caroline Corcoran, lately the belle of a Virginia town, was paying for the luxury of her desperation in a semi-slum of Dayton, Ohio.

II

She had been three years in Dayton and the situation had become intolerable. Brought up in a district where everyone was comparatively poor, where not two gowns out of fifty at country-club dances cost more than thirty dollars, lack of money had not been formidable in itself. This was very different. She came into a world not only of straining poverty but of a commonness and vulgarity that she had never touched before. It was in this regard that George Corcoran had deceived her. Somewhere he had acquired a faint patina of good breeding and he had said or done nothing to prepare her for his mother, into whose two-room flat he introduced her. Aghast, Caroline realized that she had stepped down several floors. These people had no position of any kind; George knew no one; she was literally alone in a strange city. Mrs. Corcoran disliked Caroline— disliked her good manners, her Southern ways, the added burden of her presence. For all her airs, she had brought them nothing save, eventually, a baby. Meanwhile George got a job and they moved to more spacious quarters, but mother came, too, for she owned her son, and Caroline's months went by in unimaginable dreariness. At first she was too ashamed and too poor to go home, but at the end of a year her aunt sent her money for a visit and she spent a month in Derby with her little son, proudly reticent, but unable to keep some of the truth from leaking out to her friends. Her friends had done well, or less well, but none of them had fared quite so ill as she.

But after three years, when Caroline's child became less dependent, and when the last of her affection for George had been frittered away, as his pleasant manners became debased with his own inadequacies, and when her bright, unused beauty still plagued her in the mirror, she knew that the break was coming. Not that she had specific hopes of happiness—for she accepted the idea that she had wrecked her life, and her capacity for dreaming had left her that November night three years before—but simply because conditions were intolerable. The break was heralded by a voice over the phone— a voice she remembered only as something that had done her terrible injury long ago.

“Hello,” said the voice—a strong voice with strain in it. “Mrs. George Corcoran?”

“Yes.”

“Who was Caroline Martin?”

“Who is this?”

“This is someone you haven't seen for years. Sidney Lahaye.”

After a moment she answered in a different tone: “Yes?”

“I've wanted to see you for a long time,” the voice went on.

“I don't see why,” said Caroline simply.

“I want to see you. I can't talk over the phone.”

Mrs. Corcoran, who was in the room, asked “Who is it?” forming the words with her mouth. Caroline shook her head slightly.

“I don't see why you want to see me,” she said, “and I don't think I want to see you.” Her breath came quicker; the old wound opened up again, the injury that had changed her from a happy young girl in love into whatever vague entity in the scheme of things she was now.

“Please don't ring off,” Sidney said. “I didn't call you without thinking it over carefully. I heard things weren't going well with you.”

“That's not true.” Caroline was very conscious now of Mrs. Corcoran's craning neck. “Things are going well. And I can't see what possible right you have to intrude in my affairs.”

“Wait, Caroline! You don't know what happened back in Derby after you left. I was frantic——”

“Oh, I don't care——” she cried. “Let me alone; do you hear?”

She hung up the receiver. She was outraged that this man, almost forgotten now save as an instrument of her disaster, should come back into her life!

“Who was it?” demanded Mrs. Corcoran.

“Just a man—a man I loathe.”

“Who?”

“Just an old friend.”

Mrs. Corcoran looked at her sharply. “It wasn't that man, was it?” she asked.

“What man?”

“The one you told Georgie about three years ago, when you were first married—it hurt his feelings. The man you were in love with that threw you over.”

“Oh, no,” said Caroline. “That is my affair.”

She went to the bedroom that she shared with George. If Sidney should persist and come here, how terrible—to find her sordid in a mean street.

When George came in, Caroline heard the mumble of his mother's conversation behind the closed door; she was not surprised when he asked at dinner:

“I hear that an old friend called you up.”

“Yes. Nobody you know.”

“Who was it?”

“It was an old acquaintance, but he won't call again,” she said.

“I'll bet he will,” guessed Mrs. Corcoran. “What was it you told him wasn't true?”

“That's my affair.”

Mrs. Corcoran glanced significantly at George, who said:

“It seems to me if a man calls up my wife and annoys her, I have a right to know about it.”

“You won't, and that's that.” She turned to his mother: “Why did you have to listen, anyhow?”

“I was there. You're my son's wife.”

“You make trouble,” said Caroline quietly; “you listen and watch me and make trouble. How about the woman who keeps calling up George—you do your best to hush that up.”

“That's a lie!” George cried. “And you can't talk to my mother like that! If you don't think I'm sick of your putting on a lot of dog when I work all day and come home to find——”

As he went off into a weak, raging tirade, pouring out his own self-contempt upon her, Caroline's thoughts escaped to the fifty-dollar bill, a present from her grandmother hidden under the paper in a bureau drawer. Life had taken much out of her in three years; she did not know whether she had the audacity to run away—it was nice, though, to know the money was there.

Next day, in the spring sunlight, things seemed better—and she and George had a reconciliation. She was desperately adaptable, desperately sweet-natured, and for an hour she had forgotten all the trouble and felt the old emotion of mingled passion and pity for him. Eventually his mother would go; eventually he would change and improve; and meanwhile there was her son with her own kind, wise smile, turning over the pages of a linen book on the sunny carpet. As her soul sank into a helpless, feminine apathy, compounded of the next hour's duty, of a fear of further hurt or incalculable change, the phone rang sharply through the flat.

Again and again it rang, and she stood rigid with terror. Mrs. Corcoran was gone to market, but it was not the old woman she feared. She feared the black cone hanging from the metal arm, shrilling and shrilling across the sunny room. It stopped for a minute, replaced by her heartbeats; then began again. In a panic she rushed into her room, threw little Dexter's best clothes and her only presentable dress and shoes into a suitcase and put the fifty-dollar bill in her purse. Then taking her son's hand, she hurried out of the door, pursued down the apartment stairs by the persistent cry of the telephone. The windows were open, and as she hailed a taxi and directed it to the station, she could still hear it clamoring out into the sunny morning.

III

Two years later, looking a full two years younger, Caroline regarded herself in the mirror, in a dress that she had paid for. She was a stenographer, employed by an importing firm in New York; she and young Dexter lived on her salary and on the income of ten thousand dollars in bonds, a legacy from her aunt. If life had fallen short of what it had once promised, it was at least livable again, less than misery. Rising to a sense of her big initial lie, George had given her freedom and the custody of her child. He was in kindergarten now, and safe until 5:30, when she would call for him and take him to the small flat that was at least her own. She had nothing warm near her, but she had New York, with its diversion for all purses, its curious yielding up of friends for the lonely, its quick metropolitan rhythm of love and birth and death that supplied dreams to the unimaginative, pageantry and drama to the drab.

But though life was possible it was less than satisfactory. Her work was hard, she was physically fragile; she was much more tired at the day's end than the girls with whom she worked. She must consider a precarious future when her capital should be depleted by her son's education. Thinking of the Corcoran family, she had a horror of being dependent on her son; and she dreaded the day when she must push him from her. She found that her interest in men had gone. Her two experiences had done something to her; she saw them clearly and she saw them darkly, and that part of her life was sealed up, and it grew more and more faint, like a book she had read long ago. No more love.

Caroline saw this with detachment, and not without a certain, almost impersonal, regret. In spite of the fact that sentiment was the legacy of a pretty girl, it was just one thing that was not for her. She surprised herself by saying in front of some other girls that she disliked men, but she knew it was the truth. It was an ugly phrase, but now, moving in an approximately foursquare world, she detested the compromises and evasions of her marriage. “I hate men—I, Caroline, hate men. I want from them no more than courtesy and to be left alone. My life is incomplete, then, but so be it. For others it is complete, for me it is incomplete.”

The day that she looked at her evening dress in the mirror, she was in a country house on Long Island—the home of Evelyn Murdock, the most spectacularly married of all her old Virginia friends. They had met in the street, and Caroline was there for the week-end, moving unfamiliarly through a luxury she had never imagined, intoxicated at finding that in her new evening dress she was as young and attractive as these other women, whose lives had followed more glamorous paths. Like New York the rhythm of the week-end, with its birth, its planned gayeties and its announced end, followed the rhythm of life and was a substitute for it. The sentiment had gone from Caroline, but the patterns remained. The guests, dimly glimpsed on the veranda, were prospective admirers. The visit to the nursery was a promise of future children of her own; the descent to dinner was a promenade down a marriage aisle, and her gown was a wedding dress with an invisible train.

“The man you're sitting next to,” Evelyn said, “is an old friend of yours. Sidney Lahaye—he was at Camp Rosecrans.”

After a confused moment she found that it wasn't going to be difficult at all. In the moment she had met him—such a quick moment that she had no time to grow excited—she realized that he was gone for her. He was only a smallish, handsome man, with a flushed, dark skin, a smart little black mustache and very fine eyes. It was just as gone as gone. She tried to remember why he had once seemed the most desirable person in the world, but she could only remember that he had made love to her, that he had made her think of them as engaged, and then that he had acted badly and thrown her over—into George Corcoran's arms. Years later he had telephoned like a traveling salesman remembering a dalliance in a casual city. Caroline was entirely unmoved and at her ease as they sat down at table.

But Sidney Lahaye was not relinquishing her so easily.

“So I called you up that night in Derby,” he said; “I called you for half an hour. Everything had changed for me in that ride out to camp.”

“You had a beautiful remorse.”

“It wasn't remorse; it was self-interest. I realized I was terribly in love with you. I stayed awake all night——”

Caroline listened indifferently. It didn't even explain things; nor did it tempt her to cry out on fate—it was just a fact.

He stayed near her, persistently. She knew no one else at the party; there was no niche in any special group for her. They talked on the veranda after dinner, and once she said coolly:

“Women are fragile that way. You do something to them at certain times and literally nothing can ever change what you've done.”

“You mean that you definitely hate me.”

She nodded. “As far as I feel actively about you at all.”

“I suppose so. It's awful, isn't it?”

“No. I even have to think before I can really remember how I stood waiting for you in the garden that night, holding all my dreams and hopes in my arms like a lot of flowers—they were that to me, anyhow. I thought I was pretty sweet. I'd saved myself up for that—all ready to hand it all to you. And then you came up to me and kicked me.” She laughed incredulously. “You behaved like an awful person. Even though I don't care any more, you'll always be an awful person to me. Even if you'd found me that night, I'm not at all sure that anything could have been done about it. Forgiveness is just a silly word in a matter like that.”

Feeling her own voice growing excited and annoyed, she drew her cape around her and said in an ordinary voice:

“It's getting too cold to sit here.”

“One more thing before you go,” he said. “It wasn't typical of me. It was so little typical that in the last five years I've never spent an unoccupied moment without remembering it. Not only I haven't married, I've never even been faintly in love. I've measured up every girl I've met to you, Caroline—their faces, their voices, the tips of their elbows.”

“I'm sorry I had such a devastating effect on you. It must have been a nuisance.”

“I've kept track of you since I called you in Dayton; I knew that, sooner or later, we'd meet.”

“I'm going to say good night.”

But saying good night was easier than sleeping, and Caroline had only an hour's haunted doze behind her when she awoke at seven. Packing her bag, she made up a polite, abject letter to Evelyn Murdock, explaining why she was unexpectedly leaving on Sunday morning. It was difficult and she disliked Sidney Lahaye a little bit more intensely for that.

IV

Months later Caroline came upon a streak of luck. A Mrs. O'Connor, whom she met through Evelyn Murdock, offered her a post as private secretary and traveling companion. The duties were light, the traveling included an immediate trip abroad, and Caroline, who was thin and run down from work, jumped at the chance. With astonishing generosity the offer included her boy.

From the beginning Caroline was puzzled as to what had attracted Helen O'Connor to her. Her employer was a woman of thirty, dissipated in a discreet way, extremely worldly and, save for her curious kindness to Caroline, extremely selfish. But the salary was good and Caroline shared in every luxury and was invariably treated as an equal.

The next three years were so different from anything in her past that they seemed years borrowed from the life of someone else. The Europe in which Helen O'Connor moved was not one of tourists but of seasons. Its most enduring impression was a phantasmagoria of the names of places and people—of Biarritz, of Mme de Colmar, of Deauville, of the Comte de Berme, of Cannes, of the Derehiemers, of Paris and the Chateau de Madrid. They lived the life of casinos and hotels so assiduously reported in the Paris American papers—Helen O'Connor drank and sat up late, and after a while Caroline drank and sat up late. To be slim and pale was fashionable during those years, and deep in Caroline was something that had become directionless and purposeless, that no longer cared. There was no love; she sat next to many men at table, appreciated compliments, courtesies and small gallantries, but the moment something more was hinted, she froze very definitely. Even when she was stimulated with excitement and wine, she felt the growing hardness of her sheath like a breastplate. But in other ways she was increasingly restless.

At first it had been Helen O'Connor who urged her to go out; now it became Caroline herself for whom no potion was too strong or any evening too late. There began to be mild lectures from Helen.

“This is absurd. After all, there's such a thing as moderation.”

“I suppose so, if you really want to live.”

“But you want to live; you've got a lot to live for. If my skin was like yours, and my hair——Why don't you look at some of the men that look at you?”

“Life isn't good enough, that's all,” said Caroline. “For a while I made the best of it, but I'm surer every day that it isn't good enough. People get through by keeping busy; the lucky ones are those with interesting work. I've been a good mother, but I'd certainly be an idiot putting in a sixteen-hour day mothering Dexter into being a sissy.”

“Why don't you marry Lahaye? He has money and position and everything you could want.”

There was a pause. “I've tried men. To hell with men.”

Afterward she wondered at Helen's solicitude, having long realized that the other woman cared nothing for her. They had not even mutual tastes; often they were openly antipathetic and didn't meet for days at a time. Caroline wondered why she was kept on, but she had grown more self-indulgent in these years and she was not inclined to quibble over the feathers that made soft her nest.

One night on Lake Maggiore things changed in a flash. The blurred world seen from a merry-go-round settled into place; the merry-go-round suddenly stopped.

They had gone to the hotel in Locarno because of Caroline. For months she had had a mild but persistent asthma and they had come there for rest before the gayeties of the fall season at Biarritz. They met friends, and with them Caroline wandered to the Kursaal to play mild boule at a maximum of two Swiss francs. Helen remained at the hotel.

Caroline was sitting in the bar. The orchestra was playing a Wiener Walzer, and suddenly she had the sensation that the chords were extending themselves, that each bar of three-four time was bending in the middle, dropping a little and thus drawing itself out, until the waltz itself, like a phonograph running down, became a torture. She put her fingers in her ears; then suddenly she coughed into her handkerchief.

She gasped.

The man with her asked: “What is it? Are you sick?”

She leaned back against the bar, her handkerchief with the trickle of blood clasped concealingly in her hand. It seemed to her half an hour before she answered, “No, I'm all right,” but evidently it was only a few seconds, for the man did not continue his solicitude.

“I must get out,” Caroline thought. “What is it?” Once or twice before she had noticed tiny flecks of blood, but never anything like this. She felt another cough coming and, cold with fear and weakness, wondered if she could get to the wash room.

After a long while the trickle stopped and someone wound the orchestra up to normal time. Without a word she walked slowly from the room, holding herself delicately as glass. The hotel was not a block away; she set out along the lamplit street. After a minute she wanted to cough again, so she stopped and held her breath and leaned against the wall. But this time it was no use; she raised her handkerchief to her mouth and lowered it after a minute, this time concealing it from her eyes. Then she walked on.

In the elevator another spell of weakness overcame her, but she managed to reach the door of her suite, where she collapsed on a little sofa in the antechamber. Had there been room in her heart for any emotion except terror, she would have been surprised at the sound of an excited dialogue in the salon, but at the moment the voices were art of a nightmare and only the shell of her ear registered what they said.

“I've been six months in Central Asia, or I'd have caught up with this before,” a man's voice said, and Helen answered, “I've no sense of guilt whatsoever.”

“I don't suppose you have. I'm just panning myself for having picked you out.”

“May I ask who told you this tale, Sidney?”

“Two people. A man in New York had seen you in Monte Carlo and said for a year you'd been doing nothing but buying drinks for a bunch of cadgers and spongers. He wondered who was backing you. Then I saw Evelyn Murdock in Paris, and she said Caroline was dissipating night after night; she was thin as a rail and her face looked like death. That's what brought me down here.”

“Now listen, Sidney. I'm not going to be bullied about this. Our arrangement was that I was to take Caroline abroad and give her a good time, because you were in love with her or felt guilty about her, or something. You employed me for that and you backed me. Well, I've done just what you wanted. You said you wanted her to meet lots of men.”

“I said men.”

“I've rounded up what I could. In the first place, she's absolutely indifferent, and when men find that out, they're liable to go away.”

He sat down. “Can't you understand that I wanted to do her good, not harm? She's had a rotten time; she's spent most of her youth paying for something that was my fault, so I wanted to make it up the best way I could. I wanted her to have two years of pleasure; I wanted her to learn not to be afraid of men and to have some of the gayety that I cheated her out of. With the result that you led her into two years of dissipation——” He broke off: “What was that?” he demanded.

Caroline had coughed again, irrepressibly. Her eyes were closed and she was breathing in little gasps as they came into the hall. Her hand opened and her handkerchief dropped to the floor.

In a moment she was lying on her own bed and Sidney was talking rapidly into the phone. In her dazed state the passion in his voice shook her like a vibration, and she whispered “Please! Please!” in a thin voice. Helen loosened her dress and took off her slippers and stockings.

The doctor made a preliminary examination and then nodded formidably at Sidney. He said that by good fortune a famous Swiss specialist on tuberculosis was staying at the hotel; he would ask for an immediate consultation.

The specialist arrived in bedroom slippers. His examination was as thorough as possible with the instruments at hand. Then he talked to Sidney in the salon.

“So far as I can tell without an X ray, there is a sudden and widespread destruction of tissue on one side—sometimes happens when the patient is run down in other ways. If the X ray bears me out, I would recommend an immediate artificial pneumothorax. The only chance is to completely isolate the left lung.”

“When could it be done?”

The doctor considered. “The nearest center for this trouble is Montana Vermala, about three hours from here by automobile. If you start immediately and I telephone to a colleague there, the operation might be performed tomorrow morning.”

In the big, springy car Sidney held her across his lap, surrounding with his arms the mass of pillows. Caroline hardly knew who held her, nor did her mind grasp what she had overheard. Life jostled you around so—really very tiring. She was so sick, and probably going to die, and that didn't matter, except that there was something she wanted to tell Dexter.

Sidney was conscious of a desperate joy in holding her, even though she hated him, even though he had brought her nothing but harm. She was his in these night hours, so fair and pale, dependent on his arms for protection from the jolts of the rough road, leaning on his strength at last, even though she was unaware of it; yielding him the responsibility he had once feared and ever since desired. He stood between her and disaster.

Past Dome d'Ossola, a dim, murkily lighted Italian town; past Brig, where a kindly Swiss official saw his burden and waved him by without demanding his passport; down the valley of the Rhone, where the growing stream was young and turbulent in the moonlight. Then Sierre, and the haven, the sanctuary in the mountains, two miles above, where the snow gleamed. The funicular waited: Caroline sighed a little as he lifted her from the car.

“It's very good of you to take all this trouble,” she whispered formally.

V

For three weeks she lay perfectly still on her back. She breathed and she saw flowers in her room. Eternally her temperature was taken. She was delirious after the operation and in her dreams she was again a girl in Virginia, waiting in the yard for her lover. Dress stay crisp for him—button stay put—bloom magnolia—air stay still and sweet. But the lover was neither Sidney Lahaye nor an abstraction of many men—it was herself, her vanished youth lingering in that garden, unsatisfied and unfulfilled; in her dream she waited there under the spell of eternal hope for the lover that would never come, and who now no longer mattered.

The operation was a success. After three weeks she sat up, in a month her fever had decreased and she took short walks for an hour every day. When this began, the Swiss doctor who had performed the operation talked to her seriously.

“There's something you ought to know about Montana Vermala; it applies to all such places. It's a well-known characteristic of tuberculosis that it tends to hurt the morale. Some of these people you'll see on the streets are back here for the third time, which is usually the last time. They've grown fond of the feverish stimulation of being sick; they come up here and live a life almost as gay as life in Paris—some of the champagne bills in this sanatorium are amazing. Of course, the air helps them, and we manage to exercise a certain salutary control over them, but that kind are never really cured, because in spite of their cheerfulness they don't want the normal world of responsibility. Given the choice, something in them would prefer to die. On the other hand, we know a lot more than we did twenty years ago, and every month we send away people of character completely cured. You've got that chance because your case is fundamentally easy; your right lung is utterly untouched. You can choose; you can run with the crowd and perhaps linger along three years, or you can leave in one year as well as ever.”

Caroline's observation confirmed his remarks about the environment. The village itself was like a mining town—hasty, flimsy buildings dominated by the sinister bulk of four or five sanatoriums; chastely cheerful when the sun glittered on the snow, gloomy when the cold seeped through the gloomy pines. In contrast were the flushed, pretty girls in Paris clothes whom she passed on the street, and the well-turned-out men. It was hard to believe they were fighting such a desperate battle, and as the doctor had said, many of them were not. There was an air of secret ribaldry—it was considered funny to send miniature coffins to new arrivals, and there was a continual undercurrent of scandal. Weight, weight, weight; everyone talked of weight—how many pounds one had put on last month or lost the week before.

She was conscious of death around her, too, but she felt her own strength returning day by day in the high, vibrant air, and she knew she was not going to die.

After a month came a stilted letter from Sidney. It said:

I stayed only until the immediate danger was past. I knew that, feeling as you do, you wouldn't want my face to be the first thing you saw. So I've been down here in Sierre at the foot of the mountain, polishing up my Cambodge diary. If it's any consolation for you to have someone who cares about you within call, I'd like nothing better than to stay on here. I hold myself utterly responsible for what happened to you, and many times I've wished I had died before I came into your life. Now there's only the present—to get you well.

About your son—once a month I plan to run up to his school in Fontainebleau and see him for a few days—I've seen him once now and we like each other. This summer I'll either arrange for him to go to a camp or take him through the Norwegian fjords with me, whichever plan seems advisable.

The letter depressed Caroline. She saw herself sinking into a bondage of gratitude to this man—as though she must thank an attacker for binding up her wounds. Her first act would be to earn the money to pay him back. It made her tired even to think of such things now, but it was always present in her subconscious, and when she forgot it she dreamed of it. She wrote:

Dear Sidney:

It's absurd your staying there and I'd much rather you didn't. In fact, it makes me uncomfortable. I am, of course, enormously grateful for all you've done for me and for Dexter. If it isn't too much trouble, will you come up here before you go to Paris, as I have some things to send him?

Sincerely,

Caroline M. Corcoran.

He came a fortnight later, full of a health and vitality that she found as annoying as the look of sadness that was sometimes in his eyes. He adored her and she had no use for his adoration. But her strongest sensation was one of fear—fear that since he had made her suffer so much, he might be able to make her suffer again.

“I'm doing you no good, so I'm going away,” he said. “The doctors seem to think you'll be well by September. I'll come back and see for myself. After that I'll never bother you again.”

If he expected to move her, he was disappointed.

“It may be some time before I can pay you back,” she said.

“I got you into this.”

“No, I got myself into it… Good-by, and thank you for everything you've done.”

Her voice might have been thanking him for bringing a box of candy. She was relieved at his departure. She wanted only to rest and be alone.

The winter passed. Toward the end she skied a little, and then spring came sliding up the mountain in wedges and spear points of green. Summer was sad, for two friends she had made there died within a week and she followed their coffins to the foreigners' graveyard in Sierre. She was safe now. Her affected lung had again expanded; it was scarred, but healed; she had no fever, her weight was normal and there was a bright mountain color in her cheeks.

October was set as the month of her departure, and as autumn approached, her desire to see Dexter again was overwhelming. One day a wire came from Sidney in Tibet stating that he was starting for Switzerland.

Several mornings later the floor nurse looked in to toss her a copy of the Paris Herald and she ran her eyes listlessly down the columns. Then she sat up suddenly in bed.

AMERICAN FEARED LOST IN BLACK SEA

Sidney Lahaye, Millionaire Aviator, and Pilot Missing Four Days.

Teheran, Persia, October 5——

Caroline sprang out of bed, ran with the paper to the window, looked away from it, then looked at it again.

AMERICAN FEARED LOST IN BLACK SEA

Sidney Lahaye, Millionaire Aviator——

“The Black Sea,” she repeated, as if that was the important part of the affair—“in the Black Sea.”

She stood there in the middle of an enormous quiet. The pursuing feet that had thundered in her dream had stopped. There was a steady, singing silence.

“Oh-h-h!” she said.

AMERICAN FEARED LOST IN BLACK SEA

Sidney Lahaye, Millionaire Aviator, and Pilot Missing Four Days.

Teheran, Persia, October 5——

Caroline began to talk to herself in an excited voice.

“I must get dressed,” she said; “I must get to the telegraph and see whether everything possible has been done. I must start for there.” She moved around the room, getting into her clothes. “Oh-h-h!” she whispered. “Oh-h-h!” With one shoe on, she fell face downward across the bed. “Oh, Sidney—Sidney!” she cried, and then again, in terrible protest: “Oh-h-h!” She rang for the nurse. “First, I must eat and get some strength; then I must find out about trains.”

She was so alive now that she could feel parts of herself uncurl, unroll. Her heart picked up steady and strong, as if to say, “I'll stick by you,” and her nerves gave a sort of jerk as all the old fear melted out of her. Suddenly she was grown, her broken girlhood dropped away from her, and the startled nurse answering her ring was talking to someone she had never seen before.

“It's all so simple. He loved me and I loved him. That's all there is. I must get to the telephone. We must have a consul there somewhere.”

For a fraction of a second she tried to hate Dexter because he was not Sidney's son, but she had no further reserve of hate. Living or dead, she was with her love now, held close in his arms. The moment that his footsteps stopped, that there was no more menace, he had overtaken her. Caroline saw that what she had been shielding was valueless—only the little girl in the garden, only the dead, burdensome past.

“Why, I can stand anything,” she said aloud—“anything—even losing him.”

The doctor, alarmed by the nurse, came hurrying in.

“Now, Mrs. Corcoran, you're to be quiet. No matter what news you've had, you——Look here, this may have some bearing on it, good or bad.”

He handed her a telegram, but she could not open it, and she handed it back to him mutely. He tore the envelope and held the message before her:

PICKED UP BY COALER CITY OF CLYDE STOP ALL WELL——

The telegram blurred; the doctor too. A wave of panic swept over her as she felt the old armor clasp her metallically again. She waited a minute, another minute; the doctor sat down.

“Do you mind if I sit in your lap a minute?” she said. “I'm not contagious any more, am I?”

With her head against his shoulder, she drafted a telegram with his fountain pen on the back of the one she had just received. She wrote:

PLEASE DON'T TAKE ANOTHER AEROPLANE BACK HERE. WE'VE GOT EIGHT YEARS TO MAKE UP, SO WHAT DOES A DAY OR TWO MATTER? I LOVE YOU WITH ALL MY HEART AND SOUL.

Notes

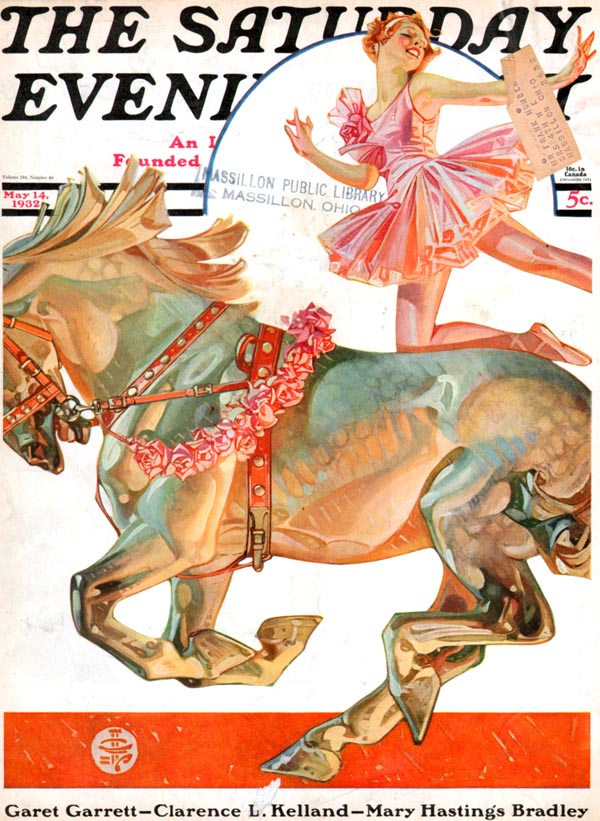

The story was probably written in Switzerland in April 1931. The Post bought the story with some reluctance, and Harold Ober reported to Fitzgerald: “The Post are taking FLIGHT AND PURSUIT but they want me to tell you that they do not feel that your last three stories have been up to the best you can do. They think it might be a good idea for you to write some American stories—that is stories laid on this side of the Atlantic and they feel that the last stories have been lacking in plot.” The Saturday Evening Postindicated its reservations about this story by holding it for a year before publishing it on 14 May 1932 in fourth position and leaving Fitzgerald's name off the cover.

Published in The Saturday Evening Post magazine (14 May 1932).

Illustrations by Henrietta McCaig Starrett.