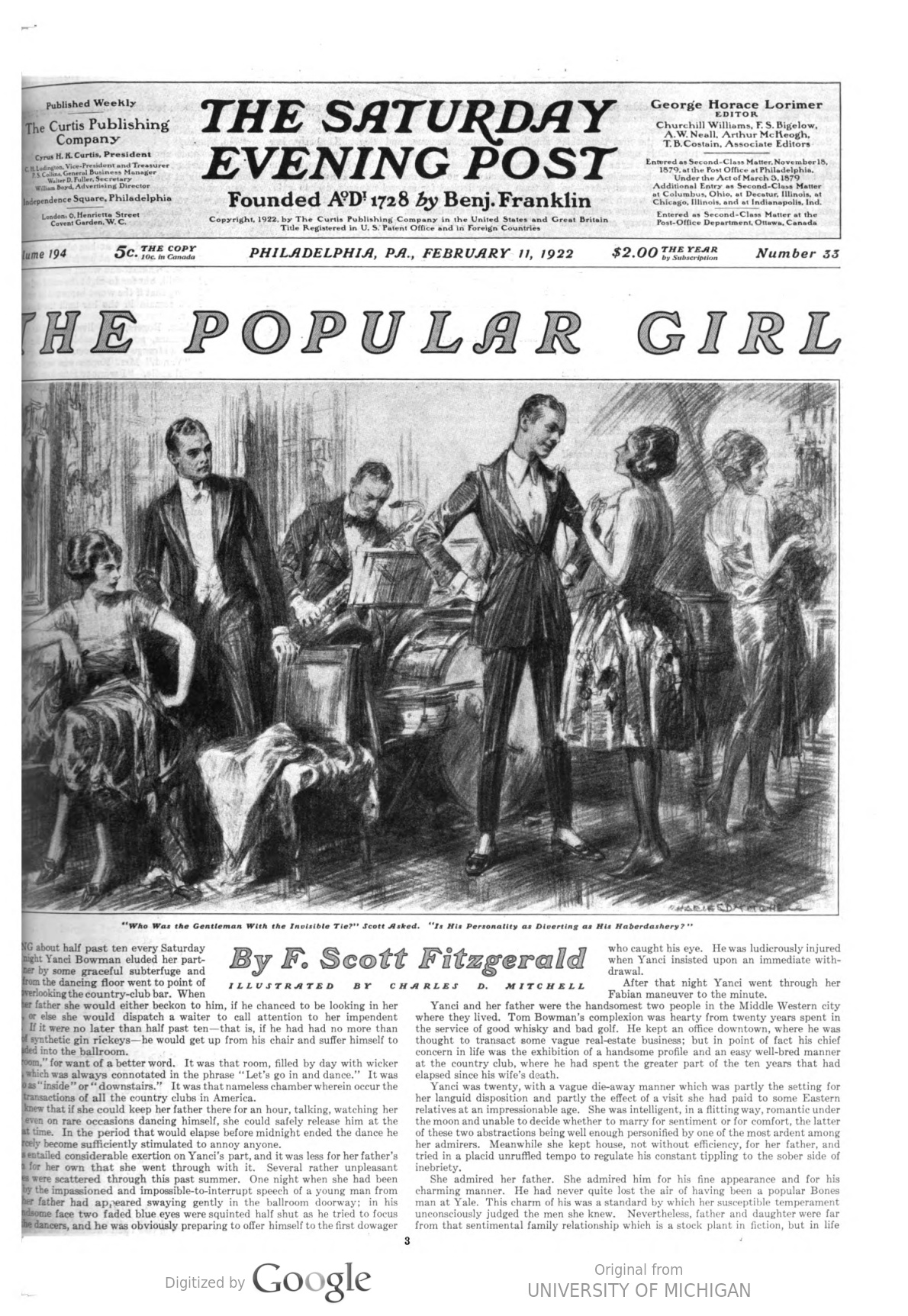

The Popular Girl

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Along about half-past ten every Saturday night Yanci Bowman eluded her partner by some graceful subterfuge and from the dancing floor went to point of vantage overlooking the country-club bar. When she saw her father she would either beckon to him, if he chanced to be looking in her direction, or else she would dispatch a waiter to call attention to her impendent presence. If it were no later than half past ten—that is, if he had had no more than an hour of synthetic gin rickeys—he would get up from his chair and suffer himself to be persuaded into the ballroom.

“Ballroom,” for want of a better word. It was that room, filled by day with wicker furniture, which was always connotated in the phrase “Let’s go in and dance.” It was referred to as “inside” or “downstairs.” It was that nameless chamber wherein occur the principal transactions of all the country clubs in America.

Yanci knew that if she could keep her father there for an hour, talking, watching her dance, or even on rare occasions dancing himself, she could safely release him at the end of that time. In the period that would elapse before midnight ended the dance he could scarcely become sufficiently stimulated to annoy anyone.

All this entailed considerable exertion on Yanci’s part, and it was less for her father’s sake than for her own that she went through with it. Several rather unpleasant experiences were scattered through this past summer. One night when she had been detained by the impassioned and impossible-to-interrupt speech of a young man from Chicago her father had appeared swaying gently in the ballroom doorway; in his ruddy handsome face two faded blue eyes were squinted half shut as he tried to focus them on the dancers, and he was obviously preparing to offer himself to the first dowager who caught his eye. He was ludicrously injured when Yanci insisted upon an immediate withdrawal.

After that night Yanci went through her Fabian maneuver to the minute.

Yanci and her father were the handsomest two people in the Middle Western city where they lived. Tom Bowman’s complexion was hearty from twenty years spent in the service of good whisky and bad golf. He kept an office downtown, where he was thought to transact some vague real-estate business; but in point of fact his chief concern in life was the exhibition of a handsome profile and an easy well-bred manner at the country club, where he had spent the greater part of the ten years that had elapsed since his wife’s death.

Yanci was twenty, with a vague die-away manner which was partly the setting for her languid disposition and partly the effect of a visit she had paid to some Eastern relatives at an impressionable age. She was intelligent, in a flitting way, a romantic under the moon and unable to decide whether to marry for sentiment or for comfort, the latter of these two abstractions being well enough personified by one of the most ardent among her admirers. Meanwhile she kept house, not without efficiency, for her father, and tried in a placid unruffled tempo to regulate his constant tippling to the sober side of inebriety.

She admired her father. She admired him for his fine appearance and for his charming manner. He had never quite lost the air of having been a popular Bones man at Yale. This charm of his was a standard by which her susceptible temperament unconsciously judged the men she knew. Nevertheless, father and daughter were far from that sentimental family relationship which is a stock plant in fiction, but in life usually exists in the mind of only the older party to it. Yanci Bowman had decided to leave her home by marriage within the year. She was heartily bored.

Scott Kimblerly, who saw her for the first time this November evening at the country club, agreed with the lady whose house guest he was that Yanci was an exquisite little beauty. With a sort of conscious sensuality surprising in such a young man—Scott was only twenty-five—he avoided an introduction that he might watch her undisturbed for a fanciful hour, and sip the pleasure or the disillusion of her conversation at the drowsy end of the evening.

“She never got over the disappointment of not meeting the Prince of Wales when he was in this country,” remarked Mrs. Orrin Rogers, following his gaze. “She said so, anyhow; whether she was serious or not, I don’t know. I hear that she has her walls simply plastered with pictures of him.”

“Who?” asked Scott suddenly.

“Why, the Prince of Wales.”

“Who has plaster pictures of him?”

“Why, Yanci Bowman, the girl you said you thought was so pretty.”

“After a certain degree of prettiness, one pretty girl is as pretty as another,” said Scott argumentatively.

“Yes, I suppose so.”

Mrs. Rogers’ voice drifted off on an indefinite note. She had never in her life compassed a generality until it had fallen familiarly on her ear from constant repetition.

“Let’s talk her over,” Scott suggested.

With a mock reproachful smile Mrs. Rogers lent herself agreeably to slander. An encore was just beginning. The orchestra trickled a light overflow of music into the pleasant green-latticed room and the two score couples who for the evening comprised the local younger set moved placidly into time with its beat. Only a few apathetic stags gathered one by one in the doorways, and to a close observer it was apparent that the scene did not attain the gayety which was its aspiration. These girls and men had known each other from childhood; and though there were marriages incipient upon the floor tonight, they were marriages of environment, of resignation, or even of boredom.

Their trappings lacked the sparkle of the seventeen-year-old affairs that took place through the short and radiant holidays. On such occasions as this, thought Scott as his eyes still sought casually for Yanci, occurred the matings of the left-overs, the plainer, the duller, the poorer of the social world; matings actuated by the same urge toward perhaps a more glamorous destiny, yet, for all that, less beautiful and less young. Scott himself was feeling very old.

But there was one face in the crowd to which his generalization did not apply. When his eyes found Yanci Bowman among the dancers he felt much younger. She was the incarnation of all in which the dance failed—graceful youth, arrogant, languid freshness and beauty that was sad and perishable as a memory in a dream. Her partner, a young man with one of those fresh red complexions ribbed with white streaks, as though he had been slapped on a cold day, did not appear to be holding her interest, and her glance fell here and there upon a group, a face, a garment, with a far-away and oblivious melancholy.

“Dark-blue eyes,” said Scott to Mrs. Rogers. “I don’t know that they mean anything except that they’re beautiful, but that nose and upper lip and chin are certainly aristocratic—if there is any such thing,” he added apologetically.

“Oh, she’s very aristocratic,” agreed Mrs. Rogers. “Her grandfather was a senator or governor or something in one of the Southern states. Her father’s very aristocratic looking too. Oh, yes, they’re very aristocratic; they’re aristocratic people.”

“She looks lazy.”

Scott was watching the yellow gown drift and submerge among the dancers.

“She doesn’t like to move. It’s a wonder she dances so well. Is she engaged? Who is the man who keeps cutting in on her, the one who tucks his tie under his collar so rakishly and affects the remarkable slanting pockets?”

He was annoyed at the young man’s persistence, and his sarcasm lacked the ring of detachment.

“Oh, that’s”—Mrs. Rogers bent forward, the tip of her tongue just visible between her lips—“that’s the O’Rourke boy. He’s quite devoted, I believe.”

“I believe,” Scott said suddenly, “that I’ll get you to introduce me if she’s near when the music stops.”

They arose and stood looking for Yanci—Mrs. Rogers, small, stoutening, nervous, and Scott Kimberly, her husband’s cousin, dark and just below medium height. Scott was an orphan with half a million of his own, and he was in this city for no more reason than that he had missed a train. They looked for several minutes, and in vain. Yanci, in her yellow dress, no longer moved with slow loveliness among the dancers.

The clock stood at half past ten.

II

“Good evening,” her father was saying to her at that moment in syllables faintly slurred. “This seems to be getting to be a habit.”

They were standing near a side stairs, and over his shoulder through a glass door Yanci could see a party of half a dozen men sitting in familiar joviality about a round table.

“Don’t you want to come out and watch for a while?” she suggested, smiling and affecting a casualness she did not feel.

“Not tonight, thanks.”

Her father’s dignity was a bit too emphasized to be convincing.

“Just come out and take a look,” she urged him. “Everybody’s here, and I want to ask you what you think of somebody.”

This was not so good, but it was the best that occurred to her.

“I doubt very strongly if I’d find anything to interest me out there,” said Tom Bowman emphatically. “I observe that f’some insane reason I’m always taken out and aged on the wood for half an hour as though I was irresponsible.”

“I only ask you to stay a little while.”

“Very considerate, I’m sure. But tonight I happ’n to be interested in a discussion that’s taking place in here.”

“Come on, father.”

Yanci put her arm through his ingratiatingly; but he released it by the simple expedient of raising his own arm and letting hers drop.

“I’m afraid not.”

“I’ll tell you,” she suggested, concealing her annoyance at this unusually protracted argument, “you come in and look, just once, and then if it bores you you can go right back.”

He shook his head.

“No, thanks.”

Then without another word he turned suddenly and reentered the bar. Yanci went back to the ballroom. She glanced easily at the stag line as she passed, and making a quick selection murmured to a man near her, “Dance with me, will you, Carty? I’ve lost my partner.”

“Glad to,” answered Carty truthfully.

“Awfully sweet of you.”

“Sweet of me? Of you, you mean.”

She looked up at him absently. She was furiously annoyed at her father. Next morning at breakfast she would radiate a consuming chill, but for tonight she could only wait, hoping that if the worst happened he would at least remain in the bar until the dance was over.

Mrs. Rogers, who lived next door to the Bowmans, appeared suddenly at her elbow with a strange young man.

“Yanci,” Mrs. Rogers was saying with a social smile, “I want to introduce Mr. Kimberly. Mr. Kimberly’s spending the weekend with us, and I particularly wanted him to meet you.”

“How perfectly slick!” drawled Yanci with lazy formality.

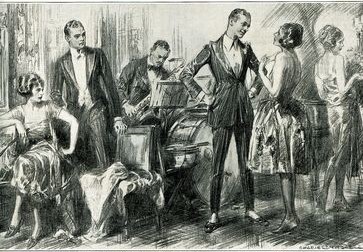

Mr. Kimberly suggested to Miss Bowman that they dance, to which proposal Miss Bowman dispassionately acquiesced. They mingled their arms in the gesture prevalent and stepped into time with the beat of the drum. Simultaneously it seemed to Scott that the room and the couples who danced up and down upon it converted themselves into a background behind her. The commonplace lamps, the rhythm of the music playing some paraphrase of a paraphrase, the faces of many girls, pretty, undistinguished or absurd, assumed a certain solidity as though they had grouped themselves in a retinue for Yanci’s languid eyes and dancing feet.

“I’ve been watching you,” said Scott simply. “You look rather bored this evening.”

“Do I?” Her dark-blue eyes exposed a borderland of fragile iris as they opened in a delicate burlesque of interest. “How perfectly kill-ing!” she added.

Scott laughed. She had used the exaggerated phrase without smiling, indeed without any attempt to give it verisimilitude. He had heard the adjectives of the year—“hectic,” “marvelous,” and “slick”—delivered casually, but never before without the faintest meaning. In this lackadaisical young beauty it was inexpressibly charming.

The dance ended. Yanci and Scott strolled toward a lounge set against the wall, but before they could take possession there was a shriek of laughter and a brawny damsel dragging an embarrassed boy in her wake skidded by them and plumped down upon it.

“How rude!” observed Yanci.

“I suppose it’s her privilege.”

“A girl with ankles like that has no privileges.”

They seated themselves uncomfortably on two stiff chairs.

“Where do you come from?” she asked of Scott with polite uninterest.

“New York.”

This having transpired, Yanci deigned to fix her eyes on him for the best part of ten seconds.

“Who was the gentleman with the invisible tie,” Scott asked rudely, in order to make her look at him, “who was giving you such a rush? I found it impossible to keep my eyes off him. Is his personality as diverting as his haberdashery?”

“I don’t know,” she drawled; “I’ve only been engaged to him for a week.”

“My Lord!” exclaimed Scott, perspiring suddenly under his eyes.

“I beg your pardon. I didn’t——”

“I was only joking,” she interrupted with a sighing laugh. “I thought I’d see what you’d say to that.”

Then they both laughed, and Yanci continued, “I’m not engaged to anyone. I’m too horribly unpopular.” Still the same key, her languorous voice humorously contradicting the content of her remark. “No one’ll ever marry me.”

“How pathetic!”

“Really,” she murmured; “because I have to have compliments all the time, in order to live, and no one thinks I’m attractive any more, so no one ever gives them to me.”

Seldom had Scott been so amused.

“Why, you beautiful child,” he cried, “I’ll bet you never hear anything else from morning till night!”

“Oh yes I do,” she responded, obviously pleased. “I never get compliments unless I fish for them.”

“Everything’s the same,” she was thinking as she gazed around her in a peculiar mood of pessimism. Same boys sober and same boys tight; same old women sitting by the walls and one or two girls sitting with them who were dancing this time last year.

Yanci had reached the stage where these country-club dances seemed little more than a display of sheer idiocy. From being an enchanted carnival where jeweled and immaculate maidens rouged to the pinkest propriety displayed themselves to strange and fascinating men, the picture had faded to a medium-sized hall where was an almost indecent display of unclothed motives and obvious failures. So much for several years! And the dance had changed scarcely by a ruffle in the fashions or a new flip in a figure of speech.

Yanci was ready to be married.

Meanwhile the dozen remarks rushing to Scott Kimberly’s lips were interrupted by the apologetic appearance of Mrs. Rogers.

“Yanci,” the older woman was saying, “the chauffeur’s just telephoned to say that the car’s broken down. I wonder if you and your father have room for us going home. If it’s the slightest inconvenience don’t hesitate to tell——”

“I know he’ll be terribly glad to. He’s got loads of room, because I came out with someone else.”

She was wondering if her father would be presentable at twelve.

He could always drive at any rate—and, besides, people who asked for a lift could take what they got.

“That’ll be lovely. Thank you so much,” said Mrs. Rogers.

Then, as she had just passed the kittenish late thirties when women still think they are persona grata with the young and entered upon the early forties when their children convey to them tactfully that they no longer are, Mrs. Rogers obliterated herself from the scene. At that moment the music started and the unfortunate young man with white streaks in his red complexion appeared in front of Yanci.

Just before the end of the end of the next dance Scott Kimberly cut in on her again.

“I’ve come back,” he began, “to tell you how beautiful you are.”

“I’m not, really,” she answered. “And, besides, you tell everyone that.”

The music gathered gusto for its finale, and they sat down upon the comfortable lounge.

“I’ve told no one that for three years,” said Scott.

There was no reason why he should have made it three years, yet somehow it sounded convincing to both of them. Her curiosity was stirred. She began finding out about him. She put him to a lazy questionnaire which began with his relationship to the Rogerses and ended, he knew not by what steps, with a detailed description of his apartment in New York.

“I want to live in New York,” she told him; “on Park Avenue, in one of those beautiful white buildings that have twelve big rooms in each apartment and cost a fortune to rent.”

“That’s what I’d want, too, if I were married. Park Avenue—it’s one of the most beautiful streets in the world, I think, perhaps chiefly because it hasn’t any leprous park trying to give it an artificial suburbanity.”

“Whatever that is,” agreed Yanci. “Anyway, Father and I go to New York about three times a year. We always go to the Ritz.”

This was not precisely true. Once a year she generally pried her father from his placid and not unbeneficent existence that she might spend a week lolling by the Fifth Avenue shop windows, lunching or having tea with some former school friend from Farmover, and occasionally going to dinner and the theater with boys who came up from Yale or Princeton for the occasion. These had been pleasant adventures—not one but was filled to the brim with colorful hours—dancing at Montmartre, dining at the Ritz, with some movie star or supereminent society woman at the next table, or else dreaming of what she might buy at Hempel’s or Waxe’s or Thrumble’s if her father’s income had but one additional naught on the happy side of the decimal. She adored New York with a great impersonal affection—adored it as only a Middle Western or Southern girl can. In its gaudy bazaars she felt her soul transported with turbulent delight, for to her eyes it held nothing ugly, nothing sordid, nothing plain.

She had stayed once at the Ritz—once only. The Manhattan, where they usually registered, had been torn down. She knew that she could never induce her father to afford the Ritz again.

After a moment she borrowed a pencil and paper and scribbled a notification “To Mr. Bowman in the grill” that he was expected to drive Mrs. Rogers and her guest home, “by request”—this last underlined. She hoped that he would be able to do so with dignity. This note she sent by a waiter to her father. Before the next dance began it was returned to her with a scrawled O. K. and her father’s initials.

The remainder of the evening passed quickly. Scott Kimberly cut in on her as often as time permitted, giving her those comforting assurances of her enduring beauty which not without a whimsical pathos she craved. He laughed at her also, and she was not so sure that she liked that. In common with all vague people, she was unaware that she was vague. She did not entirely comprehend when Scott Kimberly told her that her personality would endure long after she was too old to care whether it endured or not.

She liked best to talk about New York, and each of their interrupted conversations gave her a picture or a memory of the metropolis on which she speculated as she looked over the shoulder of Jerry O’Rourke or Carty Braden or some other beau, to whom, as to all of them, she was comfortably anesthetic. At midnight she sent another note to her father, saying that Mrs. Rogers and Mrs. Rogers’ guest would meet him immediately on the porch by the main driveway. Then, hoping for the best, she walked out into the starry night and was assisted by Jerry O’Rourke into his roadster.

III

“Good night, Yanci.” With her late escort she was standing on the curbstone in front of the rented stucco house where she lived. Mr. O’Rourke was attempting to put significance into his lingering rendition of her name. For weeks he had been straining to boost their relations almost forcibly onto a sentimental plane; but Yanci, with her vague impassivity, which was a defense against almost anything, had brought to naught his efforts. Jerry O’Rourke was an old story. His family had money; but he—he worked in a brokerage house along with most of the rest of his young generation. He sold bonds— bonds were now the thing; real estate was once the thing—in the days of the boom; then automobiles were the thing. Bonds were the thing now. Young men sold them who had nothing else to go into.

“Don’t bother to come up, please.” Then as he put his car into gear, “Call me up soon!”

A minute later he turned the corner of the moonlit street and disappeared, his cut-out resounding voluminously through the night as it declared that the rest of two dozen weary inhabitants was of no concern to his gay meanderings.

Yanci sat down thoughtfully upon the porch steps. She had no key and must wait for her father’s arrival. Five minutes later a roadster turned into the street, and approaching with an exaggerated caution stopped in front of the Rogers’ large house next door. Relieved, Yanci arose and strolled slowly down the walk. The door of the car had swung open and Mrs. Rogers, assisted by Scott Kimberly, had alighted safely upon the sidewalk; but to Yanci’s surprise Scott Kimberly, after escorting Mrs. Rogers to her steps, returned to the car. Yanci was close enough to notice that he took the driver’s seat. As he drew up at the Bowman’s curbstone Yanci saw that her father was occupying the far corner, fighting with ludicrous dignity against a sleep that had come upon him. She groaned. The fatal last hour had done its work—Tom Bowman was once more hors de combat.

“Hello,” cried Yanci as she reached the curb.

“Yanci,” muttered her parent, simulating, unsuccessfully, a brisk welcome. His lips were curved in an ingratiating grin.

“Your father wasn’t feeling quite fit, so he let me drive home,” explained Scott cheerfully as he got himself out and came up to her.

“Nice little car. Had it long?”

Yanci laughed, but without humor.

“Is he paralyzed?”

“Is who paralyze’?” demanded the figure in the car with an offended sigh.

Scott was standing by the car.

“Can I help you out, sir?”

“I c’n get out. I c’n get out,” insisted Mr. Bowman. “Just step a li’l’ out my way. Someone must have given me some ’stremely bad whisk’.”

“You mean a lot of people must have given you some,” retorted Yanci in cold unsympathy.

Mr. Bowman reached the curb with astonishing ease; but this was a deceitful success, for almost immediately he clutched at a handle of air perceptible only to himself, and was saved by Scott’s quickly proffered arm. Followed by the two men, Yanci walked toward the house in a furor of embarrassment. Would the young man think that such scenes went on every night? It was chiefly her own presence that made it humiliating for Yanci. Had her father been carried to bed by two butlers each evening she might even have been proud of the fact that he could afford such dissipation; but to have it thought that she assisted, that she was burdened with the worry and the care! And finally she was annoyed with Scott Kimberly for being there, and for his officiousness in helping to bring her father into the house.

Reaching the low porch of tapestry brick, Yanci searched in Tom Bowman’s vest for the key and unlocked the front door. A minute later the master of the house was deposited in an easy-chair.

“Thanks very much,” he said, recovering for a moment. “Sit down. Like a drink? Yanci, get some crackers and cheese, if there’s any, won’t you, dear?”

At the unconscious coolness of this Scott and Yanci laughed.

“It’s your bedtime, Father,” she said, her anger struggling with diplomacy.

“Give me my guitar,” he suggested, “and I’ll play you tune.”

Except on such occasions as this, he had not touched his guitar for twenty years. Yanci turned to Scott.

“He’ll be fine now. Thanks a lot. He’ll fall asleep in a minute and when I wake him he’ll go to bed like a lamb.”

“Well——”

They strolled together out the door.

“Sleepy?” he asked.

“No, not a bit.”

“Then perhaps you’d better let me stay here with you a few minutes until you see if he’s all right. Mrs. Rogers gave me a key so I can get in without disturbing her.”

“It’s quite all right,” protested Yanci. “I don’t mind a bit, and he won’t be any trouble. He must have taken a glass too much, and this whisky we have out here—you know! This has happened once before—last year,” she added.

Her words satisfied her; as an explanation it seemed to have a convincing ring.

“Can I sit down for a moment, anyway?” They sat side by side upon a wicker porch setee.

“I’m thinking of staying over a few days,” Scott said.

“How lovely!” Her voice had resumed its die-away note.

“Cousin Pete Rogers wasn’t well to-day, but tomorrow he’s going duck shooting, and he wants me to go with him.”

“Oh, how thrilling! I’ve always been mad to go, and Father’s always promised to take me, but he never has.”

“We’re going to be gone about three days, and then I thought I’d come back and stay over the next week-end——” He broke off suddenly and bent forward in a listening attitude.

“Now what on earth is that?”

The sounds of music were proceeding brokenly from the room they had lately left—a ragged chord on a guitar and half a dozen feeble starts.

“It’s father!” cried Yanci.

And now a voice drifted out to them, drunken and murmurous, taking the long notes with attempted melancholy:

Sing a song of cities,

Ridin on a rail,

A niggah’s ne’er so happy

As when he’s out-a jail.

“How terrible!” exclaimed Yanci. “He’ll wake up everybody in the block.”

The chorus ended, the guitar jangled again, then gave out a last harsh sprang! and was still. A moment later these disturbances were followed by a low but quite definite snore. Mr. Bowman, having indulged his musical proclivity, had dropped off to sleep.

“Let’s go to ride,” suggested Yanci impatiently. “This is too hectic for me.”

Scott arose with alacrity and they walked down to the car.

“Where’ll we go?” she wondered.

“I don’t care.”

“We might go up half a block to Crest Avenue—that’s our show street— and then ride out to the river boulevard.”

IV

As they turned into Crest Avenue the new cathedral, immense and unfinished, in imitation of a cathedral left unfinished by accident in some little Flemish town, squatted just across the way like a plump white bulldog on its haunches. The ghosts of four moonlit apostles looked down at them wanly from wall niches still littered with the white, dusty trash of the builders. The cathedral inaugurated Crest Avenue. After it came the great brownstone mass built by R. R. Comerford, the flour king, followed by a half mile of pretentious stone houses put up in the gloomy 90’s. These were adorned with monstrous driveways and porte-cocheres which had once echoed to the hoofs of good horses and with huge circular windows that corseted the second stories.

The continuity of these mausoleums was broken by a small park, a triangle of grass where Nathan Hale stood ten feet tall with his hands bound behind his back by stone cord and stared over a great bluff at the slow Mississippi. Crest Avenue ran along the bluff, but neither faced it nor seemed aware of it, for all the houses fronted inward toward the street. Beyond the first half mile it became newer, essayed ventures in terraced lawns, in concoctions of stucco or in granite mansions which imitated through a variety of gradual refinements the marble contours of the Petit Trianon. The houses of this phase rushed by the roadster for a succession of minutes; then the way turned and the car was headed directly into the moonlight which swept toward it like the lamp of some gigantic motorcycle far up the avenue.

Past the low Corinthian lines of the Christian Science Temple, past a block of dark frame horrors, a deserted row of grim red brick—an unfortunate experiment of the late 90’s—then new houses again, bright-red brick now, with trimmings of white, black iron fences and hedges binding flowery lawns. These swept by, faded, passed, enjoying their moment of grandeur; then waiting there in the moonlight to be outmoded as had the frame, cupolaed mansions of lower town and the brownstone piles of older Crest Avenue in their turn.

The roofs lowered suddenly, the lots narrowed, the houses shrank up in size and shaded off into bungalows. These held the street for the last mile, to the bend in the river which terminated the prideful avenue at the statue of Chelsea Arbuthnot. Arbuthnot was the first governor—and almost the last of Anglo-Saxon blood.

All the way thus far Yanci had not spoken, absorbed still in the annoyance of the evening, yet soothed somehow by the fresh air of Northern November that rushed by them. She must take her fur coat out of storage next day, she thought.

“Where are we now?”

As they slowed down, Scott looked up curiously at the pompous stone figure, clear in the crisp moonlight, with one hand on a book and the forefinger of the other pointing, as though with reproachful symbolism, directly at some construction work going on in the street.

“This is the end of Crest Avenue,” said Yanci, turning to him. “This is our show street.”

“A museum of American architectural failures.”

“What?”

“Nothing,” he murmured.

“I should have explained it to you. I forgot. We can go along the river boulevard if you’d like—or are you tired?”

Scott assured her that he was not tired—not in the least.

Entering the boulevard, the cement road twisted under darkling trees.

“The Mississippi—how little it means to you now!” said Scott suddenly.

“What?” Yanci looked around. “Oh, the river.”

“I guess it was once pretty important to your ancestors up here.”

“My ancestors weren’t up here then,” said Yanci with some dignity. “My ancestors were from Maryland. My father came out here when he left Yale.”

“Oh!” Scott was politely impressed.

“My mother was from here. My father came out here from Baltimore because of his health.”

“Oh!”

“Of course we belong here now, I suppose”—this with faint condescension—“as much as anywhere else.”

“Of course.”

“Except that I want to live in the East and I can’t persuade Father to,” she finished.

It was after one o’clock and the boulevard was almost deserted. Occasionally two yellow disks would top a rise ahead of them and take shape as a late-returning automobile. Except for that, they were alone in a continual rushing dark. The moon had gone down.

“Next time the road goes near the river let’s stop and watch it,” he suggested.

Yanci smiled inwardly. This remark was obviously what one boy of her acquaintance had named an international petting cue, by which was meant a suggestion that aimed to create naturally a situation for a kiss. She considered the matter. As yet the man had made no particular impression on her. He was good-looking, apparently well-to-do and from New York. She had begun to like him during the dance, increasingly as the evening had drawn to a close; then the incident of her father’s appalling arrival had thrown cold water upon this tentative warmth; and now—it was November, and the night was cold. Still——

“All right,” she agreed suddenly.

The road divided; she swerved around and brought the car to a stop in an open place high above the river.

“Well?” she demanded in the deep quiet that followed the shutting off of the engine.

“Thanks.”

“Are you satisfied here?”

“Almost. Not quite.”

“Why not?”

“I’ll tell you in a minute,” he answered. “Why is your name Yanci?”

“It’s a family name.”

“It’s very pretty.” He repeated it several times caressingly. “Yanci—it has all the grace of Nancy, and yet it isn’t prim.”

“What’s your name?” she inquired.

“Scott.”

“Scott what?”

“Kimberly. Didn’t you know?”

“I wasn’t sure. Mrs. Rogers introduced you in such a mumble.”

There was a slight pause.

“Yanci,” he repeated; “beautiful Yanci, with her dark-blue eyes and her lazy soul. Do you know why I’m not quite satisfied, Yanci?”

“Why?”

Imperceptibly she had moved her face nearer until as she waited for an answer with her lips faintly apart he knew that in asking she had granted.

Without haste he bent his head forward and touched her lips.

He sighed, and both of them felt a sort of relief—relief from the embarrassment of playing up to what conventions of this sort of thing remained.

“Thanks,” he said as he had when she first stopped the car.

“Now are you satisfied?”

Her blue eyes regarded him unsmilingly in the darkness.

“After a fashion; of course, you can never say—definitely.”

Again he bent toward her, but she stooped and started the motor. It was late and Yanci was beginning to be tired. What purpose there was in the experiment was accomplished. He had had what he asked. If he liked it he would want more, and that put her one move ahead in the game which she felt she was beginning.

“I’m hungry,” she complained. “Let’s go down and eat.”

“Very well,” he acquiesced sadly. “Just when I was enjoying—the Mississippi.”

“Do you think I’m beautiful?” she inquired almost plaintively as they backed out.

“What an absurd question!”

“But I like to hear people say so.”

“I was just about to—when you started the engine.”

Downtown in a deserted all-night lunch room they ate bacon and eggs. She was pale as ivory now. The night had drawn the lazy vitality and languid color out of her face. She encouraged him to talk to her of New York until he was beginning every sentence with, “Well now, let’s see——”

The repast over, they drove home. Scott helped her put the car in the little garage, and just outside the front door she lent him her lips again for the faint brush of a kiss. Then she went in.

The long living room which ran the width of the small stucco house was reddened by a dying fire which had been high when Yanci left and now was faded to a steady undancing glow. She took a log from the fire box and threw it on the embers, then started as a voice came out of the half darkness at the other end of the room.

“Back so soon?”

It was her father’s voice, not yet quite sober, but alert and intelligent.

“Yes. Went riding,” she answered shortly, sitting down in a wicker chair before the fire. “Then went down and had something to eat.”

“Oh!”

Her father left his place and moved to a chair nearer the fire, where he stretched himself out with a sigh. Glancing at him from the corner of her eye, for she was going to show an appropriate coldness, Yanci was fascinated by his complete recovery of dignity in the space of two hours. His graying hair was scarcely rumpled; his handsome face was ruddy as ever. Only his eyes, crisscrossed with tiny red lines, were evidence of his late dissipation.

“Have a good time?”

“Why should you care?” she answered rudely.

“Why shouldn’t I?”

“You didn’t seem to care earlier in the evening. I asked you to take two people home for me, and you weren’t able to drive your own car.”

“The deuce I wasn’t!” he protested. “I could have driven in—in a race in an arana, areaena. That Mrs. Rogers insisted that her young admirer should drive, so what could I do?”

“That isn’t her young admirer,” retorted Yanci crisply. There was no drawl in her voice now. “She’s as old as you are. That’s her niece—I mean her nephew.”

“Excuse me!”

“I think you owe me an apology.” She found suddenly that she bore him no resentment. She was rather sorry for him, and it occurred to her that in asking him to take Mrs. Rogers home she had somehow imposed on his liberty. Nevertheless, discipline was necessary—there would be other Saturday nights. “Don’t you?” she concluded.

“I apologize, Yanci.”

“Very well, I accept your apology,” she answered stiffly.

“What’s more, I’ll make it up to you.”

Her blue eyes contracted. She hoped—she hardly dared to hope that he might take her to New York.

“Let’s see,” he said. “November, isn’t it? What date?”

“The twenty-third.”

“Well, I’ll tell you what I’ll do.” He knocked the tips of his fingers together tentatively. “I’ll give you a present. I’ve been meaning to let you have a trip all fall, but business has been bad.” She almost smiled—as though business was of any consequence in his life. “But then you need a trip. I’ll make you a present of it.”

He rose again, and crossing over to his desk sat down.

“I’ve got a little money in a New York bank that’s been lying there quite a while,” he said as he fumbled in a drawer for a check book. “I’ve been intending to close out the account. Let—me—see. There’s just——” His pen scratched. “Where the devil’s the blotter? Uh!”

He came back to the fire and a pink oblong paper fluttered into her lap.

“Why, Father!”

It was a check for three hundred dollars.

“But can you afford this?” she demanded.

“It’s all right,” he reassured her, nodding. “That can be a Christmas present, too, and you’ll probably need a dress or a hat or something before you go.”

“Why,” she began uncertainly, “I hardly know whether I ought to take this much or not! I’ve got two hundred of my own downtown, you know. Are you sure——”

“Oh, yes!” He waved his hand with magnificent carelessness. “You need a holiday. You’ve been talking about New York, and I want you to go down there. Tell some of your friends at Yale and the other colleges and they’ll ask you to the prom or something. That’ll be nice. You’ll have a good time.”

He sat down abruptly in his chair and gave vent to a long sigh. Yanci folded up the check and tucked it into the low bosom of her dress.

“Well,” she drawled softly with a return to her usual manner, “you’re a perfect lamb to be so sweet about it, but I don’t want to be horribly extravagant.”

Her father did not answer. He gave another little sigh and relaxed sleepily into his chair.

“Of course I do want to go,” went on Yanci.

Still her father was silent. She wondered if he were asleep.

“Are you asleep?” she demanded, cheerfully now. She bent toward him; then she stood up and looked at him.

“Father,” she said uncertainly.

Her father remained motionless; the ruddy color had melted suddenly out of his face.

“Father!”

It occurred to her—and at the thought she grew cold, and a brassiere of iron clutched at her breast—that she was alone in the room. After a frantic instant she said to herself that her father was dead.

V

Yanci judged herself with inevitable gentleness—judged herself very much as a mother might judge a wild, spoiled child. She was not hard-minded, nor did she live by any ordered and considered philosophy of her own. To such a catastrophe as the death of her father her immediate reaction was a hysterical self-pity. The first three days were something of a nightmare; but sentimental civilization, being as infallible as Nature in healing the wounds of its more fortunate children, had inspired a certain Mrs. Oral, whom Yanci had always loathed, with a passionate interest in all such crises. To all intents and purposes Mrs. Oral buried Tom Bowman. The morning after his death Yanci had wired her maternal aunt in Chicago, but as yet that undemonstrative and well-to-do lady had sent no answer.

All day long, for four days, Yanci sat in her room upstairs, hearing steps come and go on the porch, and it merely increased her nervousness that the doorbell had been disconnected. This by order of Mrs. Oral! Doorbells were always disconnected! After the burial of the dead the strain relaxed. Yanci, dressed in her new black, regarded herself in the pier glass, and then wept because she seemed to herself very sad and beautiful. She went downstairs and tried to read a moving-picture magazine, hoping that she would not be alone in the house when the winter dark came down just after four.

This afternoon Mrs. Oral had said carpe diem to the maid, and Yanci was just starting for the kitchen to see whether she had yet gone when the reconnected bell rang suddenly through the house. Yanci started. She waited a minute, then went to the door. It was Scott Kimberly.

“I was just going to inquire for you,” he said.

“Oh! I’m much better, thank you,” she responded with the quiet dignity that seemed suited to her role.

They stood there in the hall awkwardly, each reconstructing the half-facetious, half-sentimental occasion on which they had last met. It seemed such an irreverent prelude to such a somber disaster. There was no common ground for them now, no gap that could be bridged by a slight reference to their mutual past, and there was no foundation on which he could adequately pretend to share her sorrow.

“Won’t you come in?” she said, biting her lip nervously. He followed her to the sitting room and sat beside her on the lounge. In another minute, simply because he was there and alive and friendly, she was crying on his shoulder.

“There, there!” he said, putting his arm behind her and patting her shoulder idiotically. “There, there, there!”

He was wise enough to attribute no ulterior significance to her action. She was overstrained with grief and loneliness and sentiment; almost any shoulder would have done as well. For all the biological thrill to either of them he might have been a hundred years old. In a minute she sat up.

“I beg your pardon,” she murmured brokenly. “But it’s—it’s so dismal in this house today.”

“I know just how you feel, Yanci.”

“Did I—did I—get—tears on your coat?”

In tribute to the tenseness of the incident they both laughed hysterically, and with the laughter she momentarily recovered her propriety.

“I don’t know why I should have chosen you to collapse on,” she wailed. “I really don’t just go ’round doing it in-indiscriminately on anyone who comes in.”

“I consider it—a compliment,” he responded soberly, “and I can understand the state you’re in.” Then, after a pause, “Have you any plans?”

She shook her head.

“Va-vague ones,” she muttered between little gasps. “I tho-ought I’d go down and stay with my aunt in Chicago a while.”

“I should think that’d be the best—much the best thing.” Then, because he could think of nothing else to say, he added, “Yes, very much the best thing.”

“What are you doing—here in town?” she inquired, taking in her breath in minute gasps and dabbing at her eyes with a handkerchief.

“Oh, I’m here with—with the Rogerses. I’ve been here.”

“Hunting?”

“No, I’ve just been here.”

He did not tell her that he had stayed over on her account. She might think it fresh.

“I see,” she said. She didn’t see.

“I want to know if there’s any possible thing I can do for you, Yanci. Perhaps go downtown for you, or do some errands—anything. Maybe you’d like to bundle up and get a bit of air. I could take you out to drive in your car some night, and no one would see you.”

He clipped his last word short as the inadvertency of this suggestion dawned on him. They stared at each other with horror in their eyes.

“Oh, no, thank you!” she cried. “I really don’t want to drive.”

To his relief the outer door opened and an elderly lady came in. It was Mrs. Oral. Scott rose immediately and moved backward toward the door.

“If you’re sure there isn’t anything I can do——”

Yanci introduced him to Mrs. Oral; then leaving the elder woman by the fire walked with him to the door. An idea had suddenly occurred to her.

“Wait a minute.”

She ran up the front stairs and returned immediately with a slip of pink paper in her hand.

“Here’s something I wish you’d do,” she said. “Take this to the First National Bank and have it cashed for me. You can leave the money here for me any time.”

Scott took out his wallet and opened it.

“Suppose I cash it for you now,” he suggested.

“Oh, there’s no hurry.”

“But I may as well.” He drew out three new one-hundred-dollar bills and gave them to her.

“That’s awfully sweet of you,” said Yanci.

“Not at all. May I come in and see you next time I come West?”

“I wish you would.”

“Then I will. I’m going East tonight.”

The door shut him out into the snowy dusk and Yanci returned to Mrs. Oral. Mrs. Oral had come to discuss plans.

“And now, my dear, just what do you plan to do? We ought to have some plan to go by, and I thought I’d find out if you had any definite plan in your mind.”

Yanci tried to think. She seemed to herself to be horribly alone in the world.

“I haven’t heard from my aunt. I wired her again this morning. She may be in Florida.”

“In that case you’d go there?”

“I suppose so.”

“Would you close this house?”

“I suppose so.”

Mrs. Oral glanced around with placid practicality. It occurred to her that if Yanci gave the house up she might like it for herself.

“And now,” she continued, “do you know where you stand financially?”

“All right, I guess,” answered Yanci indifferently; and then with a rush of sentiment, “There was enough for t-two; there ought to be enough for o-one.”

“I didn’t mean that,” said Mrs. Oral. “I mean, do you know the details?”

“No.”

“Well, I thought you didn’t know the details. And I thought you ought to know all the details—have a detailed account of what and where your money is. So I called up Mr. Haedge, who knew your father very well personally, to come up this afternoon and glance through his papers. He was going to stop in your father’s bank, too, by the way, and get all the details there. I don’t believe your father left any will.”

Details! Details! Details!

“Thank you,” said Yanci. “That’ll be—nice.”

Mrs. Oral gave three or four vigorous nods that were like heavy periods. Then she got up.

“And now if Hilma’s gone out I’ll make you some tea. Would you like some tea?”

“Sort of.”

“All right, I’ll make you some ni-nice tea.”

Tea! Tea! Tea!

Mr. Haedge, who came from one of the best Swedish families in town, arrived to see Yanci at five o’clock. He greeted her funereally; said that he had been several times to inquire for her; had organized the pallbearers and would now find out how she stood in no time. Did she have any idea whether or not there was a will? No? Well, there probably wasn’t one.

There was one. He found it almost at once in Mr. Bowman’s desk—but he worked there until eleven o’clock that night before he found much else. Next morning he arrived at eight, went down to the bank at ten, then to a certain brokerage firm, and came back to Yanci’s house at noon. He had known Tom Bowman for some years, but he was utterly astounded when he discovered the condition in which that handsome gallant had left his affairs.

He consulted Mrs. Oral, and that afternoon he informed a frightened Yanci in measured language that she was practically penniless. In the midst of the conversation a telegram from Chicago told her that her aunt had sailed the week previous for a trip through the Orient and was not expected back until late spring.

The beautiful Yanci, so profuse, so debonair, so careless with her gorgeous adjectives, had no adjectives for this calamity. She crept upstairs like a hurt child and sat before a mirror, brushing her luxurious hair to comfort herself. One hundred and fifty strokes she gave it, as it said in the treatment, and then a hundred and fifty more—she was too distraught to stop the nervous motion. She brushed it until her arm ached, then she changed arms and went on brushing.

The maid found her next morning, asleep, sprawled across the toilet things on the dresser in a room that was heavy and sweet with the scent of spilled perfume.

VI

To be precise, as Mr. Haedge was to a depressing degree, Tom Bowman left a bank balance that was more than ample—that is to say, more than ample to supply the post-mortem requirements of his own person. There was also twenty years’ worth of furniture, a temperamental roadster with asthmatic cylinders and two one-thousand-dollar bonds of a chain of jewelry stores which yielded 7.5 per cent interest. Unfortunately these were not known in the bond market.

When the car and the furniture had been sold and the stucco bungalow sublet, Yanci contemplated her resources with dismay. She had a bank balance of almost a thousand dollars. If she invested this she would increase her total income to about fifteen dollars a month. This, as Mrs. Oral cheerfully observed, would pay for the boarding-house room she had taken for Yanci as long as Yanci lived. Yanci was so encouraged by this news that she burst into tears.

So she acted as any beautiful girl would have acted in this emergency. With rare decision she told Mr. Haedge that she would leave her thousand dollars in a checking account, and then she walked out of his office and across the street to a beauty parlor to have her hair waved. This raised her morale astonishingly.

Indeed, she moved that very day out of the boarding house and into a small room at the best hotel in town. If she must sink into poverty, she would at least do so in the grand manner.

Sewed into the lining of her best mourning hat were the three new one-hundred-dollar bills, her father’s last present. What she expected of them, why she kept them in such a way, she did not know, unless perhaps because they had come to her under cheerful auspices and might through some gayety inherent in their crisp and virgin paper buy happier things than solitary meals and narrow hotel beds. They were hope and youth and luck and beauty; they began, somehow, to stand for all the things she had lost in that November night when Tom Bowman, having led her recklessly into space, had plunged off himself, leaving her to find the way back alone.

Yanci remained at the Hiawatha Hotel for three months, and she found that after the first visits of condolence her friends had happier things to do with their time than to spend it in her company. Jerry O’Rourke came to see her one day with a wild Celtic look in his eyes, and demanded that she marry him immediately. When she asked for time to consider he walked out in a rage. She heard later that he had been offered a position in Chicago and had left the same night.

She considered, frightened and uncertain. She had heard of people sinking out of place, out of life. Her father had once told her of a man in his class at college who had become a worker around saloons, polishing brass rails for the price of a can of beer; and she knew also that there were girls in this city with whose mothers her own mother had played as a little girl, but who were poor now and had grown common; who worked in stores and had married into the proletariat. But that such a fate should threaten her—how absurd! Why, she knew everyone! She had been invited everywhere; her great-grandfather had been governor of one of the Southern states!

She had written to her aunt in India and again in China, receiving no answer. She concluded that her aunt’s itinerary had changed, and this was confirmed when a post card arrived from Honolulu which showed no knowledge of Tom Bowman’s death, but announced that she was going with a party to the east coast of Africa. This was a last straw. The languorous and lackadaisical Yanci was on her own at last.

“Why not go to work for a while?” suggested Mr. Haedge with some irritation. “Lots of nice girls do nowadays, just for something to occupy themselves with. There’s Elsie Prendergast, who does society news on the Bulletin, and that Semple girl——”

“I can’t,” said Yanci shortly with a glitter of tears in her eyes. “I’m going East in February.”

“East? Oh, you’re going to visit someone?”

She nodded.

“Yes, I’m going to visit,” she lied, “so it’d hardly be worth while to go to work.” She could have wept, but she managed a haughty look. “I’d like to try reporting sometime, though, just for the fun of it.”

“Yes, it’s quite a lot of fun,” agreed Mr. Haedge with some irony. “Still, I suppose there’s no hurry about it. You must have plenty of that thousand dollars left.”

“Oh, plenty!”

There were a few hundred, she knew.

“Well, then I suppose a good rest, a change of scene would be the best thing for you.”

“Yes,” answered Yanci. Her lips were trembling and she rose, scarcely able to control herself. Mr. Haedge seemed so impersonally cold. “That’s why I’m going. A good rest is what I need.”

“I think you’re wise.”

What Mr. Haegde would have thought had he seen the dozen drafts she wrote that night of a certain letter is problematical. Here are two of the earlier ones. The bracketed words are proposed substitutions:

Dear Scott: Not having seen you since that day I was such a silly ass and wept on your coat, I thought I’d write and tell you that I’m coming East pretty soon and would like you to have lunch [dinner] with me or something. I have been living in a room [suite] at the Hiawatha Hotel, intending to meet my aunt, with whom I am going to live [stay], and who is coming back from China this month [spring]. Meanwhile I have a lot of invitations to visit, etc., in the East, and I thought I would do it now. So I’d like to see you——

This draft ended here and went into the wastebasket. After an hour’s work she produced the following:

My dear Mr. Kimberly: I have often [sometimes] wondered how you’ve been since I saw you. I am coming East next month before going to visit my aunt in Chicago, and you must come and see me. I have been going out very little, but my physician advises me that I need change, so I expect to shock the proprieties by some very gay visits in the East——

Finally in despondent abandon she wrote a simple note without explanation or subterfuge, tore it up and went to bed. Next morning she identified it in the wastebasket and decided it was the best one after all and sent him a fair copy. It ran:

Scott: Just a line to tell you I will be at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel from February seventh, probably for ten days. If you phone me some rainy afternoon I’ll invite you to tea.

Sincerely, Yanci Bowman.

VII

Yanci was going to the Ritz for no more reason than that she had once told Scott Kimberly that she always went there. When she reached New York—a cold New York, a strangely menacing New York, quite different from the gay city of theaters and hotel-corridor rendezvous that she had known—there was exactly two hundred dollars in her purse.

It had taken a large part of her bank account to live, and she had at last broken into her sacred three hundred dollars to substitute pretty and delicate quarter-mourning clothes for the heavy black she had laid away.

Walking into the hotel at the moment when its exquisitely dressed patrons were assembling for luncheon, it drained at her confidence to appear bored and at ease. Surely the clerks at the desk knew the contents of her pocketbook. She fancied even that the bell boys were snickering at the foreign labels she had steamed from an old trunk of her father’s and pasted on her suitcase. This last thought horrified her. Perhaps the very hotels and steamers so grandly named had long since been out of commission!

As she stood drumming her fingers on the desk she was wondering whether if she were refused admittance she could muster a casual smile and stroll out coolly enough to deceive two richly dressed women standing near. It had not taken long for the confidence of twenty years to evaporate. Three months without security had made an ineffaceable mark on Yanci’s soul.

“Twenty-four sixty-two,” said the clerk callously.

Her heart settled back into place as she followed the bell boy to the elevator, meanwhile casting a nonchalant glance at the two fashionable women as she passed them. Were their skirts long or short?—longer, she noticed.

She wondered how much the skirt of her new walking suit could be let out.

At luncheon her spirits soared. The head waiter bowed to her. The light rattle of conversation, the subdued hum of the music soothed her. She ordered supreme of melon, eggs Susette and an artichoke, and signed her room number to the check with scarcely a glance at it as it lay beside her plate. Up in her room, with the telephone directory open on the bed before her, she tried to locate her scattered metropolitan acquaintances. Yet even as the phone numbers, with their supercilious tags, Plaza, Circle, and Rhinelander, stared out at her, she could feel a cold wind blow at her unstable confidence. These girls, acquaintances of school, of a summer, of a house party, even of a week-end at a college prom—what claim or attraction could she, poor and friendless, exercise over them? They had their loves, their dates, their week’s gayety planned in advance. They would almost resent her inconvenient memory.

Nevertheless, she called four girls. One of them was out, one at Palm Beach, one in California. The only one to whom she talked said in a hearty voice that she was in bed with grippe, but would phone Yanci as soon as she felt well enough to go out. Then Yanci gave up the girls. She would have to create the illusion of a good time in some other manner. The illusion must be created—that was part of her plan.

She looked at her watch and found that it was three o’clock. Scott Kimberly should have phoned before this, or at least left some word. Still, he was probably busy—at a club, she thought vaguely, or else buying some neckties. He would probably call at four.

Yanci was well aware that she must work quickly. She had figured to a nicety that one hundred and fifty dollars carefully expended would carry her through two weeks, no more. The idea of failure, the fear that at the end of that time she would be friendless and penniless had not begun to bother her.

It was not the first time that for amusement, for a coveted invitation or for curiosity she had deliberately set out to capture a man; but it was the first time she had laid her plans with necessity and desperation pressing in on her.

One of her strongest cards had always been her background, the impression she gave that she was popular and desired and happy. This she must create now, and apparently out of nothing. Scott must somehow be brought to think that a fair portion of New York was at her feet.

At four she went over to Park Avenue, where the sun was out, walking and the February day was fresh and odorous of spring and the high apartments of her desire lined the street with radiant whiteness. Here she would live on a gay schedule of pleasure. In these smart not-to-be-entered-without-a-card women’s shops she would spend the morning hours acquiring and acquiring, ceaselessly and without thought of expense; in these restaurants she would lunch at noon in company with other fashionable women, orchid-adorned always, and perhaps bearing an absurdly dwarfed Pomeranian in her sleek arms.

In the summer—well, she would go to Tuxedo, perhaps to an immaculate house perched high on a fashionable eminence, where she would emerge to visit a world of teas and balls, of horse shows and polo. Between the halves of the polo game the players would cluster around her in their white suits and helmets, admiringly, and when she swept away, bound for some new delight, she would be followed by the eyes of many envious but intimidated women.

Every other summer they would, of course, go abroad. She began to plan a typical year, distributing a few months here and a few months there until she—and Scott Kimberly, by implication—would become the very auguries of the season, shifting with the slightest stirring of the social barometer from rusticity to urbanity, from palm to pine.

She had two weeks, no more, in which to attain to this position. In an ecstasy of determined emotion she lifted up her head toward the tallest of the tall white apartments.

“It will be too marvelous!” she said to herself.

For almost the first time in her life her words were not too exaggerated to express the wonder shining in her eyes.

VIII

About five o’clock she hurried back to the hotel, demanding feverishly at the desk if there had been a telephone message for her. To her profound disappointment there was nothing. A minute after she had entered her room the phone rang.

“This is Scott Kimberly.”

At the words a call to battle echoed in her heart.

“Oh, how do you do?”

Her tone implied that she had almost forgotten him. It was not frigid—it was merely casual.

As she answered the inevitable question as to the hour when she had arrived, a warm glow spread over her. Now that, from a personification of all the riches and pleasure she craved, he had materialized as merely a male voice over the telephone, her confidence became strengthened. Male voices were male voices. They could be managed; they could be made to intone syllables of which the minds behind them had no approval. Male voices could be made sad or tender or despairing at her will. She rejoiced. The soft clay was ready to her hand.

“Won’t you take dinner with me tonight?” Scott was suggesting.

“Why”—perhaps not, she thought; let him think of her tonight—“I don’t believe I’ll be able to,” she said. “I’ve got an engagement for dinner and the theater. I’m terribly sorry.”

Her voice did not sound sorry—it sounded polite. Then as though a happy thought had occurred to her as to a time and place where she could work him into her list of dates, “I’ll tell you: Why don’t you come around here this afternoon and have tea with me?”

He would be there immediately. He had been playing squash and as soon as he took a plunge he would arrive. Yanci hung up the phone and turned with a quiet efficiency to the mirror, too tense to smile.

She regarded her lustrous eyes and dusky hair in critical approval. Then she took a lavender tea gown from her trunk and began to dress.

She let him wait seven minutes in the lobby before she appeared; then she approached him with a friendly, lazy smile.

“How do you do?” she murmured. “It’s marvelous to see you again. How are you?” And, with a long sigh, “I’m frightfully tired. I’ve been on the go ever since I got here this morning; shopping and then tearing off to luncheon and a matinee. I’ve bought everything I saw. I don’t know how I’m going to pay for it all.”

She remembered vividly that when they had first met she had told him, without expecting to be believed, how unpopular she was. She could not risk such a remark now, even in jest. He must think that she had been on the go every minute of the day.

They took a table and were served with olive sandwiches and tea. He was so good-looking, she thought, and marvelously dressed. His gray eyes regarded her with interest from under immaculate ash-blond hair. She wondered how he passed his days, how he liked her costume, what he was thinking of at that moment.

“How long will you be here?” he asked.

“Well, two weeks, off and on. I’m going down to Princeton for the February prom and then up to a house party in Westchester County for a few days. Are you shocked at me for going out so soon? Father would have wanted me to, you know. He was very modern in all his ideas.”

She had debated this remark on the train. She was not going to a house party. She was not invited to the Princeton prom. Such things, nevertheless, were necessary to create the illusion. That was everything—the illusion.

“And then,” she continued, smiling, “two of my old beaus are in town, which makes it nice for me.”

She saw Scott blink and she knew that he appreciated the significance of this.

“What are your plans for this winter?” he demanded. “Are you going back West?”

“No. You see, my aunt returns from India this week. She’s going to open her Florida house, and we’ll stay there until the middle of March. Then we’ll come up to Hot Springs and we may go to Europe for the summer.”

This was all the sheerest fiction. Her first letter to her aunt, which had given the bare details of Tom Bowman’s death, had at last reached its destination. Her aunt had replied with a note of conventional sympathy and the announcement that she would be back in America within two years if she didn’t decide to live in Italy.

“But you’ll let me see something of you while you’re here,” urged Scott, after attending to this impressive program. “If you can’t take dinner with me tonight, how about Wednesday—that’s the day after tomorrow?”

“Wednesday? Let’s see.” Yanci’s brow was knit with imitation thought. “I think I have a date for Wednesday, but I don’t know for certain. How about phoning me tomorrow, and I’ll let you know? Because I want to go with you, only I think I’ve made an engagement.”

“Very well, I’ll phone you.”

“Do—about ten.”

“Try to be able to—then or any time.”

“I’ll tell you—if I can’t go to dinner with you Wednesday I can go to lunch surely.”

“All right,” he agreed. “And we’ll go to a matinee.”

They danced several times. Never by word or sign did Yanci betray more than the most cursory interest in him until just at the end, when she offered her hand to say good-by.

“Good-by, Scott.”

For just the fraction of a second—not long enough for him to be sure it had happened at all, but just enough so that he would be reminded, however faintly, of that night on the Mississippi boulevard—she looked into his eyes. Then she turned quickly and hurried away.

She took her dinner in a little tea room around the corner. It was an economical dinner which cost a dollar and a half. There was no date concerned in it at all, and no man—except an elderly person in spats who tried to speak to her as she came out the door.

IX

Sitting alone in one of the magnificent moving-picture theaters—a luxury which she thought she could afford—Yanci watched Mae Murray swirl through splendidly imagined vistas, and meanwhile considered the progress of the first day. In retrospect it was a distinct success. She had given the correct impression both as to her material prosperity and as to her attitude toward Scott himself. It seemed best to avoid evening dates. Let him have the evenings to himself, to think of her, to imagine her with other men, even to spend a few lonely hours in his apartment, considering how much more cheerful it might be if——Let time and absence work for her.

Engrossed for a while in the moving picture, she calculated the cost of the apartment in which its heroine endured her movie wrongs. She admired its slender Italian table, occupying only one side of the large dining room and flanked by a long bench which gave it an air of medieval luxury. She rejoiced in the beauty of Mae Murray’s clothes and furs, her gorgeous hats, her short-seeming French shoes. Then after a moment her mind returned to her own drama; she wondered if Scott were already engaged, and her heart dipped at the thought. Yet it was unlikely. He had been too quick to phone her on her arrival, too lavish with his time, too responsive that afternoon.

After the picture she returned to the Ritz, where she slept deeply and happily for almost the first time in three months. The atmosphere around her no longer seemed cold. Even the floor clerk had smiled kindly and admiringly when Yanci asked for her key.

Next morning at ten Scott phoned. Yanci, who had been up for hours, pretended to be drowsy from her dissipation of the night before.

No, she could not take dinner with him on Wednesday. She was terribly sorry; she had an engagement, as she had feared. But she could have luncheon and go to a matinee if he would get her back in time for tea.

She spent the day roving the streets. On top of a bus, though not on the front seat, where Scott might possibly spy her, she sailed out Riverside Drive and back along Fifth Avenue just at the winter twilight, and her feeling for New York and its gorgeous splendors deepened and redoubled. Here she must live and be rich, be nodded to by the traffic policemen at the corners as she sat in her limousine—with a small dog—and here she must stroll on Sunday to and from a stylish church, with Scott, handsome in his cutaway and tall hat, walking devotedly at her side.

At luncheon on Wednesday she described for Scott’s benefit a fanciful two days. She told of a motoring trip up the Hudson and gave him her opinion of two plays she had seen with—it was implied—adoring gentlemen beside her. She had read up very carefully on the plays in the morning paper and chosen two concerning which she could garner the most information.

“Oh,” he said in dismay, “you’ve seen Dulcy? I have two seats for it—but you won’t want to go again.”

“Oh, no, I don’t mind,” she protested truthfully. “You see, we went late, and anyway I adored it.”

But he wouldn’t hear of her sitting through it again—besides he had seen it himself. It was a play Yanci was mad to see, but she was compelled to watch him while he exchanged the tickets for others, and for the poor seats available at the last moment. The game seemed difficult at times.

“By the way,” he said afterwards as they drove back to the hotel in a taxi, “you’ll be going down to the Princeton prom tomorrow, won’t you?”

She started. She had not realized that it would be so soon or that he would know of it.

“Yes,” she answered coolly. “I’m going down tomorrow afternoon.”

“On the 2:20, I suppose,” Scott commented; and then, “Are you going to meet the boy who’s taking you down—at Princeton?”

For an instant she was off her guard.

“Yes, he’ll meet the train.”

“Then I’ll take you to the station,” proposed Scott. “There’ll be a crowd and you may have trouble getting a porter.”

She could think of nothing to say, no valid objection to make. She wished she had said that she was going by automobile, but she could conceive of no graceful and plausible way of amending her first admission.

“That’s mighty sweet of you.”

“You’ll be at the Ritz when you come back?”

“Oh, yes,” she answered. “I’m going to keep my rooms.”

Her bedroom was the smallest and least expensive in the hotel.

She concluded to let him put her on the train for Princeton; in fact, she saw no alternative. Next day as she packed her suitcase after luncheon the situation had taken such hold of her imagination that she filled it with the very things she would have chosen had she really been going to the prom. Her intention was to get out at the first stop and take the train back to New York.

Scott called for her at half past one and they took a taxi to the Pennsylvania Station. The train was crowded as he had expected, but he found her a seat and stowed her grip in the rack overhead.

“I’ll call you Friday to see how you’ve behaved,” he said.

“All right. I’ll be good.”

Their eyes met and in an instant, with an inexplicable, only half-conscious rush of emotion, they were in perfect communion. When Yanci came back, the glance seemed to say, ah, then——

A voice startled her ear:

“Why, Yanci!”

Yanci looked around. To her horror she recognized a girl named Ellen Harley, one of those to whom she had phoned upon her arrival.

“Well, Yanci Bowman! You’re the last person I ever expected to see. How are you?”

Yanci introduced Scott. Her heart was beating violently.

“Are you coming to the prom? How perfectly slick!” cried Ellen. “Can I sit here with you? I’ve been wanting to see you. Who are you going with?”

“No one you know.”

“Maybe I do.”

Her words, falling like sharp claws on Yanci’s sensitive soul, were interrupted by an unintelligible outburst from the conductor. Scott bowed to Ellen, cast at Yanci one level glance and then hurried off.

The train started. As Ellen arranged her grip and threw off her fur coat Yanci looked around her. The car was gay with girls whose excited chatter filled the damp, rubbery air like smoke. Here and there sat a chaperon, a mass of decaying rock in a field of flowers, predicting with a mute and somber fatality the end of all gayety and all youth. How many times had Yanci herself been one of such a crowd, careless and happy, dreaming of the men she would meet, of the battered hacks waiting at the station, the snow-covered campus, the big open fires in the clubhouses, and the imported orchestra beating out defiant melody against the approach of morning.

And now—she was an intruder, uninvited, undesired. As at the Ritz on the day of her arrival, she felt that at any instant her mask would be torn from her and she would be exposed as a pretender to the gaze of all the car.

“Tell me everything!” Ellen was saying. “Tell me what you’ve been doing. I didn’t see you at any of the football games last fall.”

This was by way of letting Yanci know that she had attended them herself.

The conductor was bellowing from the rear of the car, “Manhattan Transfer next stop!”

Yanci’s cheeks burned with shame. She wondered what she had best do—meditating a confession, deciding against it, answering Ellen’s chatter in frightened monosyllables—then, as with an ominous thunder of brakes the speed of the train began to slacken, she sprang on a despairing impulse to her feet.

“My heavens!” she cried. “I’ve forgotten my shoes! I’ve got to go back and get them.”

Ellen reacted to this with annoying efficiency.

“I’ll take your suitcase,” she said quickly, “and you can call for it. I’ll be at the Charter Club.”

“No!” Yanci almost shrieked. “It’s got my dress in it!”

Ignoring the lack of logic in her own remark, she swung the suitcase off the rack with what seemed to her a super-human effort and went reeling down the aisle, stared at curiously by the arrogant eyes of many girls. When she reached the platform just as the train came to a stop she felt weak and shaken. She stood on the hard cement which marks the quaint old village of Manhattan Transfer and tears were streaming down her cheeks as she watched the unfeeling cars speed off to Princeton with their burden of happy youth.

After half an hour’s wait Yanci got on a train and returned to New York. In thirty minutes she had lost the confidence that a week had gained for her. She came back to her little room and lay down quietly upon the bed.

X

By Friday Yanci’s spirits had partly recovered from their chill depression. Scott’s voice over the telephone in mid-morning was like a tonic, and she told him of the delights of Princeton with convincing enthusiasm, drawing vicariously upon a prom she had attended there two years before. He was anxious to see her, he said. Would she come to dinner and the theater that night? Yanci considered, greatly tempted. Dinner—she had been economizing on meals, and a gorgeous dinner in some extravagant show place followed by a musical comedy appealed to her starved fancy, indeed; but instinct told her that the time was not yet right. Let him wait. Let him dream a little more, a little longer.

“I’m too tired, Scott,” she said with an air of extreme frankness; “that’s the whole truth of the matter. I’ve been out every night since I’ve been here, and I’m really half dead. I’ll rest up on this house party over the week-end and then I’ll go to dinner with you any day you want me.”

There was a minute’s silence while she held the phone expectantly.

“Lot of resting up you’ll do on a house party,” he replied; “and, anyway, next week is so far off. I’m awfully anxious to see you, Yanci.”

“So am I, Scott.”

She allowed the faintest caress to linger on his name. When she had hung up she felt happy again. Despite her humiliation on the train her plan had been a success. The illusion was still intact; it was nearly complete. And in three meetings and half a dozen telephone calls she had managed to create a tenser atmosphere between them than if he had seen her constantly in the moods and avowals and beguilements of an out-and-out flirtation.

When Monday came she paid her first week’s hotel bill. The size of it did not alarm her—she was prepared for that—but the shock of seeing so much money go, of realizing that there remained only one hundred and twenty dollars of her father’s present, gave her a peculiar sinking sensation in the pit of her stomach. She decided to bring guile to bear immediately, to tantalize Scott by a carefully planned incident, and then at the end of the week to show him simply and definitely that she loved him.

As a decoy for Scott’s tantalization she located by telephone a certain Jimmy Long, a handsome boy with whom she had played as a little girl and who had recently come to New York to work. Jimmy Long was deftly maneuvered into asking her to go to a matinee with him on Wednesday afternoon. He was to meet her in the lobby at two.

On Wednesday she lunched with Scott. His eyes followed her every motion, and knowing this she felt a great rush of tenderness toward him. Desiring at first only what he represented, she had begun half unconsciously to desire him also. Nevertheless, she did not permit herself the slightest relaxation on that account. The time was too short and the odds too great. That she was beginning to love him only fortified her resolve.

“Where are you going this afternoon?” he demanded.

“To a matinee—with an annoying man.”

“Why is he annoying?”

“Because he wants me to marry him and I don’t believe I want to.”

There was just the faintest emphasis on the word “believe.” The implication was that she was not sure—that is, not quite.

“Don’t marry him.”

“I won’t—probably.”

“Yanci,” he said in a low voice, “do you remember a night on that boulevard——”

She changed the subject. It was noon and the room was full of sunlight. It was not quite the place, the time. When he spoke she must have every aspect of the situation in control. He must say only what she wanted said; nothing else would do.

“It’s five minutes to two,” she told him, looking at her wrist watch. “We’d better go. I’ve got to keep my date.”

“Do you want to go?”

“No,” she answered simply.