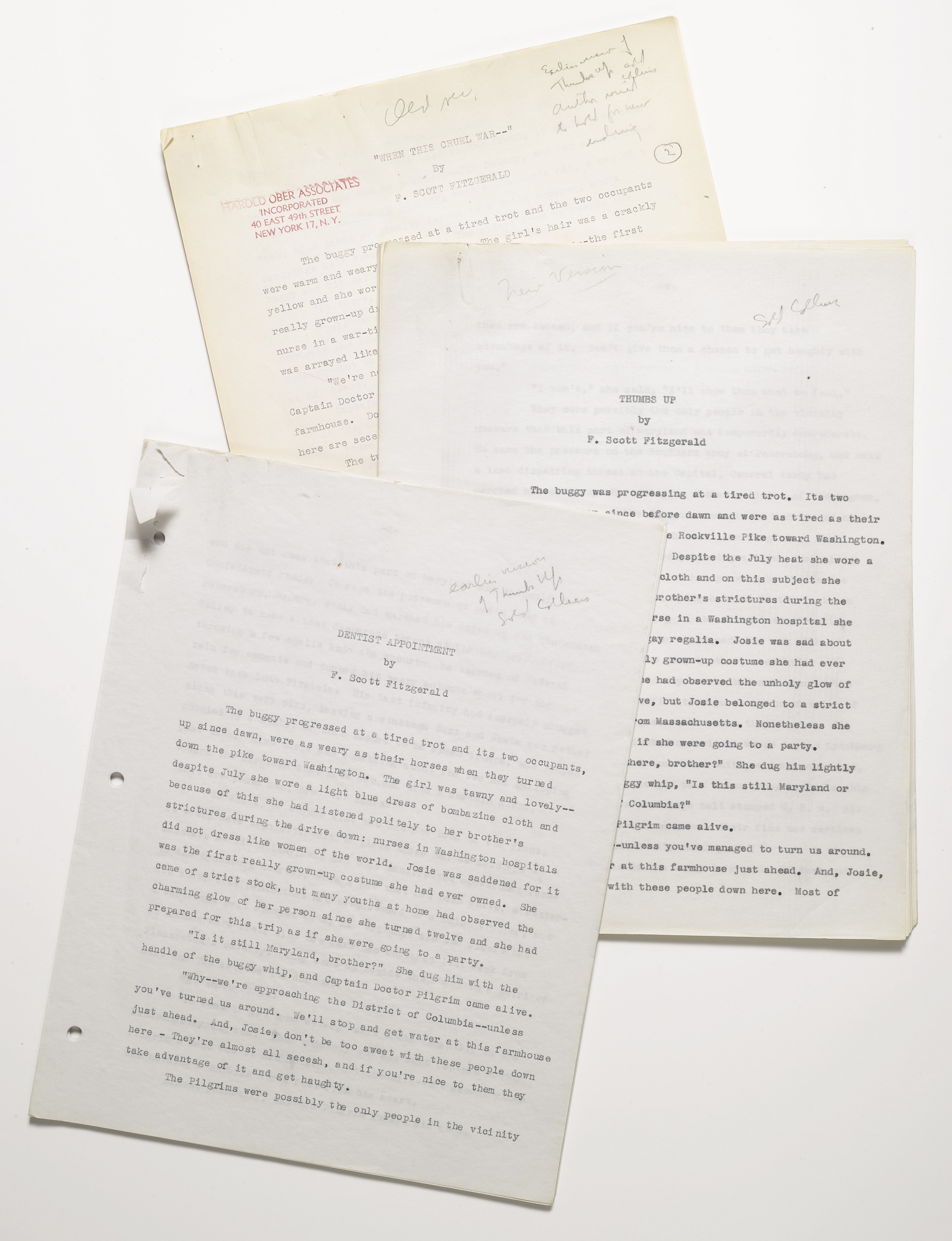

Dentist Appointment

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

The buggy progressed at a tired trot and its two occupants, up since dawn, were as weary as their horses when they turned down the pike toward Washington. The girl was tawny and lovely—despite July she wore a light blue dress of bombazine cloth and because of this she had listened politely to her brother’s strictures during the drive down: nurses in Washington hospitals did not dress like women of the world. Josie was saddened for it was the first really grown-up costume she had ever owned. She came of strict stock, but many youths at home had observed the charming glow of her person since she turned twelve and she had prepared for this trip as if she were going to a party.

“Is it still Maryland, brother?” She dug him with the handle of the buggy whip, and Captain Doctor Pilgrim came alive.

“Why—we’re approaching the District of Columbia—unless you’ve turned us around. We’ll stop and get water at this farmhouse just ahead. And, Josie, don’t be too sweet with these people down here—They’re almost all secesh, and if you’re nice to them they take advantage of it and get haughty.”

The Pilgrims were possibly the only people in the vicinity who did not know that this part of Maryland was suddenly in Confederate hands. To ease the pressure on Lee’s army at Petersburg, General Early had marched his corps up the Shenandoah Valley to make a last desperate threat at the capital. After throwing a few shells into the suburbs, he learned of Federal rein for cements and turned his weary columns about for the march back into Virginia. His last infantry had scarcely slogged along this very pike, leaving a stubborn dust, and Josie was rather puzzled by a number of what seemed to be armed tramps who limped past them. Also there was something about the two men galloping toward the carriage that made her ask with a certain alarm, “What are those men, brother? Secesh?”

To Josie, or anyone who had not been to the front, it would have been difficult to place these men as soldiers—soldiers—Tib Dulany, who had once contributed occasional verse to the Lynchburg Courier, wore a hat that that had been white, a butternut coat, blue pants that had been issued to a Union trooper, and a cartridge belt stamped C.S.A. All that the two riders had in common were their fine new carbines captured last week from Pleasanton’s cavalry. They came up beside the buggy in a whirl of dust and Tib saluted the doctor.

“Hi there, Yank!”

“We want to get some water,” said Josie haughtily to the handsomest young man. Then suddenly she saw that Captain Doctor Pilgrim’s hand was at his holster, but immobile—the second rider was holding a carbine three feet from his heart.

Almost painfully, Captain Pilgrim raised his arms.

“What is this—a raid?” he demanded.

Josie felt a hand reaching about her and shrank forward; Tib was taking her brother’s revolver.

“What is this?” repeated Dr. Pilgrim. “Are you guerillas?”

“Who are you?” the riders demanded. Without waiting for an answer Tib said “Young lady, turn in yonder at the farmhouse. You can get water there.”

He realised suddenly that she was lovely, that she was frightened and brave, and he added: “Nobody’s going to hurt you. We just aiming to detain you a little.”

“Will you tell me who you are?” Captain Pilgrim demanded.

“Cultivate calm!” Tib advised him. “You’re inside Lee’s lines now.”

“Lee’s lines!” Captain Pilgrim cried. “You think every time you Mosby murderers come out of your hills and cut a telegraph—”

The team, barely started, jolted to a stop—the second trooper had grabbed the reins, and turned black eyes upon the northerner.

“One word more about Mosby and I’ll clean your little old face with dandelions.”

“The officer isn’t informed of the news, Wash,” said Tib. “He doesn’t know he’s a prisoner of the Army of Northern Virginia.”

Captain Pilgrim looked at them incredulously; Wash released the reins and they drove to the farmhouse. Only as the foliage parted and he saw two dozen horses attended by grey-clad orderlies, did he realize that his information was indeed several days behind.

“Is Lee’s army here?”

“You didn’t know? Why, right now Abe Lincoln’s in the kitchen washing dishes—and General Grant’s upstairs making the beds.”

“Ah-h-h!” grunted Captain Pilgrim.

“Say, Wash, I sure would like to be in Washington tonight when Jeff Davis rides in. That Yankee rebellion didn’t last long, did it?”

Josie suddenly believed it and her world was crashing around her. The Boys in Blue, the Union forever—Mine eyes have seen the Glory of the Coming of the Lord. Her eyes filled with hot tears.

“You can’t take my brother prisoner—he’s not really an officer, he’s a doctor. He was wounded at Cold Harbor—”

“Doctor, eh? Don’t know anything about teeth, does he?” asked Tib, dismounting at the porch.

“Oh yes—that’s his specialty.”

“So you’re a tooth doctor? That’s what we been looking for all over Maryland-My-Maryland. If you’ll be so kind as to come in here you can pull a tooth of a real Bonaparte, a cousin of Emperor Napoleon III. No joke—he’s attached to General Early’s staff. He’s been bawling his head off for an hour but the medical men went on with the ambulances.”

An officer came out on the porch, gave a nervous ear to a crackling of rifles in the distance, and bent an eye upon the buggy.

“We found a tooth specialist, Lieutenant,” said Tib. “Providence sent him into our lines and if Napoleon is still—”

“Thank God!” the officer exclaimed. “Bring him in. We didn’t know whether to take the Prince along or leave him.”

Suddenly a glimpse of the Confederacy was staged for Josie on the vine- covered veranda. There was a sudden egress: a spidery man in a shabby riding coat with faded stars, followed by two younger men cramming papers into a canvas sack. Then a miscellany of officers, one on a single crutch, one stripped to an undershirt with the gold star of a general pinned to a bandage on his shoulder. The general air was of nervous gaiety but Josie saw the reflection of disappointment in their tired eyes. Perceiving her, they made a single gesture: their dozen right hands rose to their dozen hats and they bowed in her direction.

Josie bowed back stiffly, trying unsuccessfully to bring hauteur and pious reproach into her face. In a moment they swung into their saddles. General Early looked for a moment at the city that he could not conquer, a city that another Virginian had conceived arbitrarily out of a swamp eighty years before.

“No change in orders,” he said to the aide at his stirrup. “Tell Mosby that I want couriers every half hour up to Harper’s Ferry.”

“Yes, sir.”

The aide spoke to him in a low voice and his sun-strained eyes focused on Dr. Pilgrim in the buggy.

“I understand you’re a dentist,” he said. “Prince Napoleon has been with us as an observer. Pull out his tooth or whatever he needs. These two troopers will stay with you. Do well by him and they’ll let you go without parole when you’ve finished.”

There was the clop and crunch of mounted men moving down a lane, and in a minute the last sally of the Army of Northern Virginia faded swiftly into the distance.

“We got a dentist here for Prince Napoleon,” said Tib to a French aide-de- camp who came out of the farmhouse.

“That’s excellent news.” He led the way inside. “The Prince is in such agony.”

“The doctor is a Yankee,” Tib continued. “One of us will have to stay while he’s operating.”

The stout invalid across the room, a gross miniature of his world-shaking uncle, tore his hand from a groaning mouth and sat upright in an armchair.

“Operating!” he cried. “My God! Is he going to operate?”

Dr. Pilgrim looked suspiciously at Tib.

“My sister—where will she be?”

“I’ve put her into the parlor, Doctor. Wash, you stay here.”

“I'll need hot water,” said Dr. Pilgrim, “and my instrument case from the buggy.”

Prince Napoleon groaned again.

“Will you cut my head off of my neck? Ah, cette vie barbare!”

Tib consoled him politely.

“This doctor is a demon for teeth, Prince Napoleon.”

“I am a trained surgeon,” said Dr. Pilgrim stiffly. “Now, sir, will you take off that hat?”

The Prince removed the wide white Cordoba which topped a miscellaneous costume of red tail-coat, French uniform breeches and dragoon boots.

“Can we trust this medicine if he is a Yankee? How can I know he will not cut to kill? Does he know I am a French citizen?”

“Prince, if he doesn’t do well by you we got some apple trees outside and plenty rope.”

Tib went into the parlor where Miss Josie sat on the edge of a horsehair sofa.

“What are you going to do to my brother?”

Sorry for her lovely, anxious face, Tib said: “I’m more worried what he’s about to do to the Prince.”

An anguished howl arose from the library.

“You hear that?” Tib said. “The Prince is the one to worry about.”

“Are you going to send us to that Libby Prison?”

“Most certainly not, Madame. You’re going to be here till your brother fixes up the Prince; then as soon as our cavalry pickets come past you can continue your journey.”

Josie relaxed.

“I thought all the fighting was down in Virginia.”

“It is. That’s where we’re heading, I reckon—this is the third time I’ve ridden into Maryland with the army and it’s the third time I’m heading back with it.”

She looked at him for the first time with a certain human interest.

“What did my brother mean when he said you were a gorilla?”

“I reckon because I didn’t shave since yesterday.” He laughed. “It’s ‘guerrilla,’ not ‘gorilla.’ When it’s a Yankee on detached service they call him a scout but when it’s one of us they call us spies and string us up.”

“Any soldier not in uniform is a spy, isn’t he?”

“I’m in uniform—look at my buckle. Believe it or not, Miss Pilgrim, I was a smart-looking trooper when I rode out of Lynchburg four years ago.”

He told her how he had been dressed that day and Josie listened, thinking it was not unlike when the first young volunteers had got on the train at Chillicothe, Ohio.

“—with a big red ribbon of my mother’s for a sash. One of the girls got out in front of the troop and read a poem I wrote.”

“Say the poem,” Josie exclaimed, “I would so enjoy hearing it.”

Tib considered. “Reckon I’ve forgot it. All I remember is ‘Lynchburg, thy guardsmen bid thy hills farewell.’”

“I love it.” Forgetting the errand on which Lynchburg’s guardsmen were bent she added, “I certainly wish you remembered the rest of it.”

Came a scream from across the hall and a medley of French. The distraught face of the aide-de-camp appeared at the door.

“He has pulled out not just the tooth but the estomac—He has done him to the death!”

A face pushed over his shoulder.

“Say, Tib—the Yank got the tooth.”

“Did he?” said Tib absently. As Wash withdrew he turned back to Josie.

“I certainly would like to write a few lines to express my admiration of you.”

“This is so sudden,” she said lightly.

She might have spoken for herself too—nothing is much more sudden than first sight.

II

A minute later Wash looked back in.

“Say, Tib, we oughtn’t to stay here. A patrol just skinned by shootin back from the saddle. Ain’t we fixin to leave? This here Doctor knows we’re Mosby’s men.”

“Will you leave without us?” the aide demanded suspiciously.

“We sure will,” said Tib. “The Prince can observe the war from the Yankee angle for a while. Miss Pilgrim, I bid you a sad, I may say, a most unwilling goodbye.”

Peering hastily into the library Tib found the Prince so far recovered as to be sitting upright, panting and gasping.

“You are an artiste,” he was assuring Dr. Pilgrim. “After all the terror I still live! In Paris sometimes if they take the tooth from you you have hemorrhage and die.”

Wash called from the door.

“Come on, Tib!”

There were shots very near now. The two scouts had scarcely unhitched their horses when Wash exclaimed: “Hell fire!” and pointed down the drive where half a dozen Federal troopers had come into view behind the foliage of the far gate. Wash swung his carbine one-handed to his right shoulder and reached for a cartridge in his pouch.

“I'll take the two on the left,” he said.

Standing concealed by their horses they waited.

“Maybe we could run for it,” Tib suggested.

“The place has got seven-rail fences.”

“Don’t fire till they get nearer.”

Leisurely the file of cavalry trotted up the drive. Even after four years on detached sendee, Tib hated to shoot from ambush, but he concentrated on the business and the front sight of his carbine came into line with the center of the Yankee corporal’s tunic.

“Got your mark, Wash?”

“Think so.”

“When they break we’ll ride through ‘em.”

But the ill luck of Southern arms that day was with them before they could loose a shot. A heavy body flung against Tib and pinioned him. A voice shouted beside his ear.

“Men, they’re rebels here!”

Even as Tib turned, wrestling desperately with Dr. Pilgrim, the Northern patrol stopped, drew pistols. Wash was bobbing desperately from side to side to get a shot at Pilgrim, but the Doctor maneuvered Tib’s body in between.

In a few seconds it was over. Wash loosed a single shot but the Federals were around them before he was in his saddle. Furiously, the two young men faced their captors. Dr. Pilgrim spoke sharply to the Federal corporal:

“These are Mosby’s men.”

Those years were bitter on the border. The Federals slew Wash when he made an attempt to get away by grabbing at the corporal’s revolver. Tib, still struggling, was trussed up at the porch rail.

“There’s a good tree,” one of the Federals said, “and there’s a rope on the swing.”

The corporal glanced at Dr. Pilgrim.

“You say he’s one of Mosby’s men?”

“I’m in the Seventh Virginia Cavalry,” said Tib.

“Are you one of Mosby’s men?”

“None of your business.”

“All right, boys, get the rope.”

Dr. Pilgrim’s austere presence asserted itself again.

“I don’t think you should hang him but certainly this type of irregular has got to be discouraged.”

“We hang them up by their thumbs, sometimes,” suggested the corporal.

“Then do that,” said Dr. Pilgrim. “He spoke of hanging me.”

… By six that evening the road outside was busy again. Two brigades of Sheridan’s finest were on Early’s trail, harassing him down the valley. Mail and fresh vegetables were moving toward the capital again and the raid was over, except for a few stragglers who lay exhausted along the Rockville Pike.

In the farmhouse it was quiet. Prince Napoleon was waiting for an ambulance from Washington. There was no sound there—except from Tib, who, as his skin slipped off his thumbs, repeated aloud to himself fragments of his own political verses. When he could think of no more verses he tried singing a song that they had sung much that year:

We'll follow the feather of Mosby tonight;

And lift from the Yankees our horse-flesh and leather.

We'll follow the feather, Mosby’s grey feather…

When it was full dark and the sentry was dozing on the porch someone came who knew where the step-ladder was, because she had heard them dump it down after stringing up Tib. When she had half sawed through the rope she went back to her room for pillows and moved the table under him and laid the pillows on it.

She did not need any precedents for what she was doing. When Tib fell with a grunting gasp, murmuring “Nothing to be ashamed of,” she poured half a bottle of sherry wine over his hands. Then, suddenly sick herself, she ran back to her room.

III

After a war there are some for whom it is over and many unreconciled. Dr. Pilgrim, irritated by the government’s failure to bring the south to its knees, left Washington and set out for Minnesota by rail and river. He and Josie arrived at St. Paul in the autumn of 1866.

“We are out of the area of infection,” he said. “Why, back in Washington rebels already walk the streets unmolested. But slavery has never polluted this air.”

The rude town was like a great fish just hauled out of the Mississippi and still leaping and squirming on the bank. Around the wharves spread a card- house city of twelve thousand people, complete with churches, stores, stables and saloons. Walking the littered streets, the newcomers stepped aside for stages and prairie wagons, bull teams and foraging chickens—but there were also some tall hats and much tall talk, for the railroad was coming through. The general note was of heady confidence and high excitement.

“You must get some cowhide boots,” Josie remarked, but Dr. Pilgrim was engrossed in his thought.

“There will be southerners out here,” Dr. Pilgrim ruminated. “Josie, there’s something I haven’t told you because it may alarm you. When we were in Chicago I saw that man of Mosby’s—the one we captured.”

Drums beat in her head—drums of remembered pain. Her eyes had seen the glory of the coming of the Lord, and then seen the glory of the Lord hung up by the thumbs…

“I had an idea he recognized me too,” Dr. Pilgrim continued. “I may have been wrong.”

“You ought to be glad he’s alive,” said Josie in an odd voice.

“Glad? Frankly, that wasn’t my thought. A Mosby guerilla would be capable of vindictiveness and revenge—when such a man comes west he means to seek out desperadoes like himself, the kind who rob the mail and hold up trains.”

“That’s absurd,” she protested, “you’re the one who’s vindictive. You don’t know anything about his private character. As a matter of fact—” She hesitated. “I thought he had a rather fine inner nature.”

Such a statement was equivalent to giddy approval and Dr. Pilgrim looked at her with resentment. He did not altogether approve of Josie—in Washington she had had three proposals within the year, actually six but, rather than be classed as a flirt, she did not count the ones she stopped unfinished. But almost from the moment her brother mentioned Tib Dulany she looked rather breathlessly for him among the swarms of new arrivals in front of the hotel.

Tib came to St. Paul with no knowledge of this. He had not recognized Dr. Pilgrim in Chicago, nor were his thoughts either vindictive or desperate. He was going to join some former comrades in arms further west, and Josie came into his range of vision as a pretty stranger having breakfast at the hotel lunch counter. Then suddenly he recognized her or rather he recognized a memory and an emotion deep in himself, for momentarily he could not say her name.

And Josie, in the instant that she saw him, looked at his hands, at where his thumbs should be but were not, and the smoky room went round about her.

“I'm sorry I startled you,” he said. “You know me, don’t you?”

“Yes.”

“My name is Dulany. In Maryland—”

“I know.”

There was an embarrassed pause. With an effort she asked:

“Did you just arrive?”

“Yes. I didn’t expect to see you—I don’t know what to say. I’ve often thought—”

… Josie’s brother was out seeking an office—at any moment he might walk in the door. Instinctively Josie threw reserve aside.

“My brother is here with me,” she said. “He saw you in Chicago. He thinks you may have some idea of—revenge.”

“He’s wrong,” Tib said, “I can honestly say that at no time have I had such an idea.”

“The war isn’t over for my brother. And when I saw—your poor hands—”

“That’s past,” he said. “I’d like to talk to you as if it had never happened.”

“He wouldn’t like it,” she said, and then added, “but I would. If he knew you were at this hotel—”

“I can go to another.”

There was a sudden interruption. Tib was hailed by three young men across the room who started over toward him.

“I want to see you,” he whispered hurriedly. “Couldn’t you meet me this afternoon in front of the post office?”

“Tonight is better. Seven o’clock.”

Josie paid her bill and went out, followed by the eyes of the new arrivals, a dark young man with undefeated southern eyes burning under a panama and two red-headed twins.

“It didn’t take you long, Tib,” said the former, Mr. Ben Cary, late of Stuart’s staff. “We’ve been here three days and we haven’t found anything like that.”

“Let’s get out of here,” said Tib, “I have reasons.”

Seated in another restaurant, they demanded, “What’s it all about, Tib? Is there a husband in the wind?”

“Not a husband, “ said Tib. “There’s a Yankee brother—he’s a dentist.”

The three men exchanged a glance.

“A dentist. Boy, you interest us strangely. Why are you running away from a dentist?”

“Some trouble during the war. Suppose you tell me why you’re in St. Paul. I was starting out to meet you in Leesburg tomorrow.”

“We’re here on business, Tib—or rather it’s a matter of life and death. We’re having Indian trouble up there. About two thousand Sioux are camped on our door-step threatening to tear our fences down.”

“You’ve come to get help?”

“Fat chance. Do you reckon the government would back a rebel colony against a privileged Indian. No, we’re on our own. We think we can persuade the chief that we’re his friends, if we can do him a big favor. Tell us more about the dentist.”

“Forget the dentist,” said Tib impatiently. “He just arrived here. I don’t like him and that’s the whole story.”

“Just arrived here,” repeated Cary meditatively, “that’s very interesting. They have three here already and we’ve been to see them all and they’re the most cowardly white men that ever breathed—” He broke off and demanded, “What’s this man’s name?”

“Pilgrim,” said Tib, “but I won’t introduce you.”

Another glance passed between them and they were suddenly uncommunicative. Tomorrow they would all start for Leesburg—Tib was relieved that it was not tonight. But his relief would have been brief had he heard their conversation when he left them.

“If this dentist has just arrived he’s still traveling, so to speak—a little bit further won’t hurt him.”

“We won’t consult him. We’ll have the consultation out where the patient is.”

“Old Tib would enjoy it—right in the Mosby line. But then again he might object. It’s been a long time since I saw a girl like that.”

IV

Dr. Pilgrim began the installation of his office that evening—Josie gave an excuse to remain at the hotel to sew. She slipped out at seven to the post office where Tib waited with a rented rig, and they drove up on the cliff above the river. The town twinkled below, a mirage of metropolis against the darkening prairie.

“That represents the future,” he said. “It doesn’t seem much to leave Virginia for—but I’m not sorry.”

“I'm not either,” Josie said. “When we got here yesterday I felt a little sad and lost. But today it’s different.”

“The trouble is that now I don’t want to go any further,” he said. “Do you know what made me change?”

Josie didn’t want him to tell her yet.

“It must have been the little signs of the east,” she said. “Somebody’s planted some lilac trees and I saw a big grand piano going through the street.”

“There’ll be no pianos where I’m going, but then there hasn’t been much music in Virginia for the last few years.” He hesitated. “Sometime I’d like you to see Virginia—the valley in Spring.”

“‘Lynchburg thy guardsmen bid thy hills farewell’,” she quoted.

“You remember that?” He smiled. “But I didn’t want to stay there. My father and two brothers were killed and when Mother died this spring it was all gone. And then life seemed to start all over again when I saw your pretty face in the hotel.”

This time she didn’t change the subject.

“I remembered waking up that morning two years ago and crawling off through the woods trying to think whether a girl cut me down or whether it was part of the nightmare. Afterwards I liked to believe it was you.”

“It was me.” She shivered. “We really ought to start back. I must be there when my brother comes in.”

“Give me a minute to think about it,” he begged, “it’s a very beautiful thought. Of course I would have fallen in love with you anyhow.”

“You hardly know me. I’m just the only girl you’ve met here—” She was really talking to herself, and not very convincingly. Then after a minute neither of them were talking at all. In such a little time, that place, that hour, the shadow cast by the horse and buggy under the stars had suddenly become the center of the world.

After a while she drew away and Tib unwillingly flapped the rein on the horse’s back. They should have made plans now but they were under a spell more pervasive than the breath of northern autumn in the night. They would meet tomorrow somehow—the same place, the same time. They were so sure that they would meet—

Dr. Pilgrim had not returned and Josie, all wide awake, walked up the street to his office, a frame building with rooms for professional men. She stepped into a scene of confusion. A group gathered around the colored scrubwoman trying to find out exactly what had happened. One thing was certain—before Dr. Pilgrim had so much as hung out his shingle he had been violently spirited away.

“They wasn’t Indians,” cried the negress, “they was white people dressed up like Indians. They said the chief was sick. Whenever I told them they wasn’t Indians they begun whoopin’ and carryin’ on, sayin’ they was goin’ to scalp me sure enough. But two of them had red hair and they talk like they come from Virginia.”

The life went out of Josie—and terror took its place. No vindictiveness, no revenge—and this was what his friends had done while he gallantly occupied her attention. An eye for an eye—no better than men had been a thousand years ago.

Traces of the guilty parties appeared. A number of citizens had noticed the “Indians” when they entered the building, and assumed it was horse-play. Later that night a wagon, accompanied by riders who answered the negress’s description, had driven out of town on the run.

Josie remembered the name Leesburg, a trading post, two days journey west of St. Paul. She had letters of introduction not yet presented and next day some sympathetic merchants helped her get the ear of the commandant at Fort Snelling. At noon, accompanied by a detail of six troopers, she started for Leesburg on the Fargo stage.

V

Dr. Pilgrim had once before been kidnapped for professional reasons, so the experience did not even have the charm of novelty. To be carried off by imitation Indians somewhat paralyzed his faculties at first, but when he learned the reason for the abduction he expressed this opinion fluently:

“For the sake of a savage!” he raged. “Why, Indians don’t know what dentistry is: they have their medicine men—or nature takes care of them.”

They sat in a wooden blockhouse, one of the half dozen edifices of Leesburg. A caucus of citizens, all hailing from below the Mason-Dixon line, listened with interest to the conversation.

“Nature didn’t take care of Chief Red Weed,” said Ben Cary, “so you’ll have to. You see before he had the toothache he didn’t mind the fences—now he’s calling in his braves from over the Dakota line. Like to ride out to their village and take a look?”

“I don’t want to see hide or hair of any Indians!”

“It isn’t his hide—it’s his teeth.”

“Confound his teeth! They can rot away for all I care.”

“Now, doctor, that seems kind of inhuman. The Chief is a savage, like you say, but the government says he’s a noble savage. If he was a darky wouldn’t you go for that tooth?”

“That’s different.”

“Not so different. This Indian is mighty dark, isn’t he boys? Especially when you get him in his wigwam. While you’re operating you can just pretend he’s a nigger—then you won’t mind it a bit.”

The tone of bitterness only stiffened the doctor’s resolution.

“It’s the insult to my profession. Would you kidnap a surgeon to sew up an injured wildcat?”

“Red Weed isn’t so wild. He may even take you into his tribe. You’d be the only redskin dentist in the world.”

“The honor does not appeal to me.”

Cary tried another tack.

“In a way, you’ve got us, Doctor—we can’t force you. But we believe that if you fix up one sick Indian you can save women and children from what happened here in ’62.”

“That’s a matter for the army—they handled the rebellion.”

He was on thin ice now but there was no answer except a long silence.

“Boys, we’ll let the doctor think it over.” Cary turned to the Indian interpreter, “Say to Red Weed that the white medicine man won’t come to the village today because he must purify himself on his arrival.”

An hour after this interview Tib Dulany accompanied by a guide rode into Leesburg on lathered ponies; he had read the morning paper in St. Paul and set out long before the stage. He was wildly angry when he dismounted and faced Ben Cary.

“You damned fools! They’ll send troops from St. Paul.”

“It was an emergency, Tib—we acted the best way we knew how.”

He explained the situation but Tib was unsympathetic.

“If anybody shanghaied me I’d rather be shot than do what they wanted.”

“Didn’t you do a little body-snatching for Mosby in your day?”

“There’s no comparison. What do you reckon that girl thinks of me now?”

“That’s a pity, Tib, but—”

Gradually as he talked of the imminent danger the image of Josie temporarily receded from Tib’s mind.

“Pilgrim’s a stubborn man,” he said. “Does he know I’m one of you?”

“I thought you wouldn’t want that mentioned.”

“Well, it seems I’m in it now. Maybe I can do something. Tell him there’s another patient wants to see him—that and nothing more.”

Dr. Pilgrim had braced himself resolutely against persuasion—and when Tib came to the door a tirade was on his tongue. But the words were not spoken—his jaw dropped and he stared as his visitor said quietly:

“I’ve come to see you about my thumbs.”

Then Dr. Pilgrim’s eyes fell upon what a pair of gloves had hidden in Chicago.

“An odd sight,” said Tib. “I found it an inconvenience at first. But then discovered I could think about it two ways, as a battle wound, or as something else.”

The doctor tried to summon up the moral superiority so essential to his self-respect.

“In other days,” continued Tib, “It would have been quite simple. These Indians out here would understand. They have a torture that isn’t very different—put thongs through a man’s chest and hang him up till he collapses.” He broke off. “Dr. Pilgrim, up to now I’ve tried to consider my thumbs as a war wound, but out here closer to nature I begin to think I was wrong. Perhaps I ought to collect my bill.”

“What are you going to do to me?”

“That depends. You did a cruel thing. And you don’t seem to feel any regret about it.”

“It was perhaps an extreme measure,” admitted the doctor uneasily. “To that extent I am sorry.”

“That’s a lot from you, but it isn’t enough. All I asked of you that day in Maryland was to pull that Frenchman’s tooth. That wasn’t so terrible, was it?”

“No, it wasn’t. I tell you I do regret the incident.”

Tib got to his feet.

“I believe you. And to prove it you’ll come along with me and pull another tooth. Then we’ll call the account square.”

The doctor was trapped, but in his moment of relief he could find no words of protest. Irascibly he picked up his bag and a few minutes later a little party started for the Indian village through the twilight.

At the outpost they were delayed while a message went to Red Weed; word came to pass them through. Arrived at the chief's wigwam Dr. Pilgrim, accompanied by an interpreter, stepped inside.

Five minutes later a triumphant yell arose from the squaws and children who lined the street—the Fargo stage, surrounded by braves in war paint, drove up with four disarmed soldiers and half a dozen civilians inside.

VI

Instinctively Tib ran to the side of the stage but at Josie’s expression his throat choked up and no words came. He turned to the cavalry corporal.

“Dr. Pilgrim is safe. At this moment he’s in the chief's wigwam working on him. If we sit tight we’ll all get out of this.”

“What’s it all mean?”

Ben Cary answered him:

“It means things are about to break here but your Colonel wouldn’t listen to us because we’re Virginians.”

“I’m in this now,” Tib said to Josie, “but I didn’t know anything about it that night.”

From the wigwam issued a stream of groans followed by a wailing cry and the warriors crowded in around the tepee.

“He’d better be good,” said Cary grimly.

Ten minutes passed. The complaining moans rose and fell. The face of the interpreter appeared in a flap of the tent and he said something rapidly in Sioux, translating it for the benefit of the whites.

“Him got two teeth.”

And then to Tib’s wonder Josie’s voice called to him out of the dusk.

“It’s all right, isn’t it?” she said.

“We don’t know yet.”

“I mean everything’s all right. It doesn’t even seem strange to be here.”

“You believe me then?”

“I believe you, Tib—but it doesn’t seem to matter now.”

Her eyes with that bright yet veiled expression, described as starry, looked past the wailing Indians, the anxious whites, the ominous black triangle of the tepee, at some vision of her own against the sky.

“Whenever we’re together,” she said, “one place is as good as any other. See—they know it, they’re looking at us. We’re not strangers here—they won’t harm us. They know we’re at home.”

Hand in hand Tib and Josie waited and a cool wind blew the curls around her forehead. From time to time the light moved inside the wigwam and they could distinguish the doctor’s voice and the guttural of the interpreter. One by one the Indians had squatted on the ground and a soldier was taking a food hamper from the wagon. The village was quiet and there was suddenly a flag of stars in the bright sky. Josie was the only person there who knew that there was nothing to worry about now, because she and Tib owned everything around them now further than their eyes could see. She felt very safe and warm with his hand on her shoulder while Dr. Pilgrim kept his appointment across the still darkness.

Notes

Written in 1937, an early version of “The End of Hate”story.

Published in I'd Die For You collection.

Not illustrated.