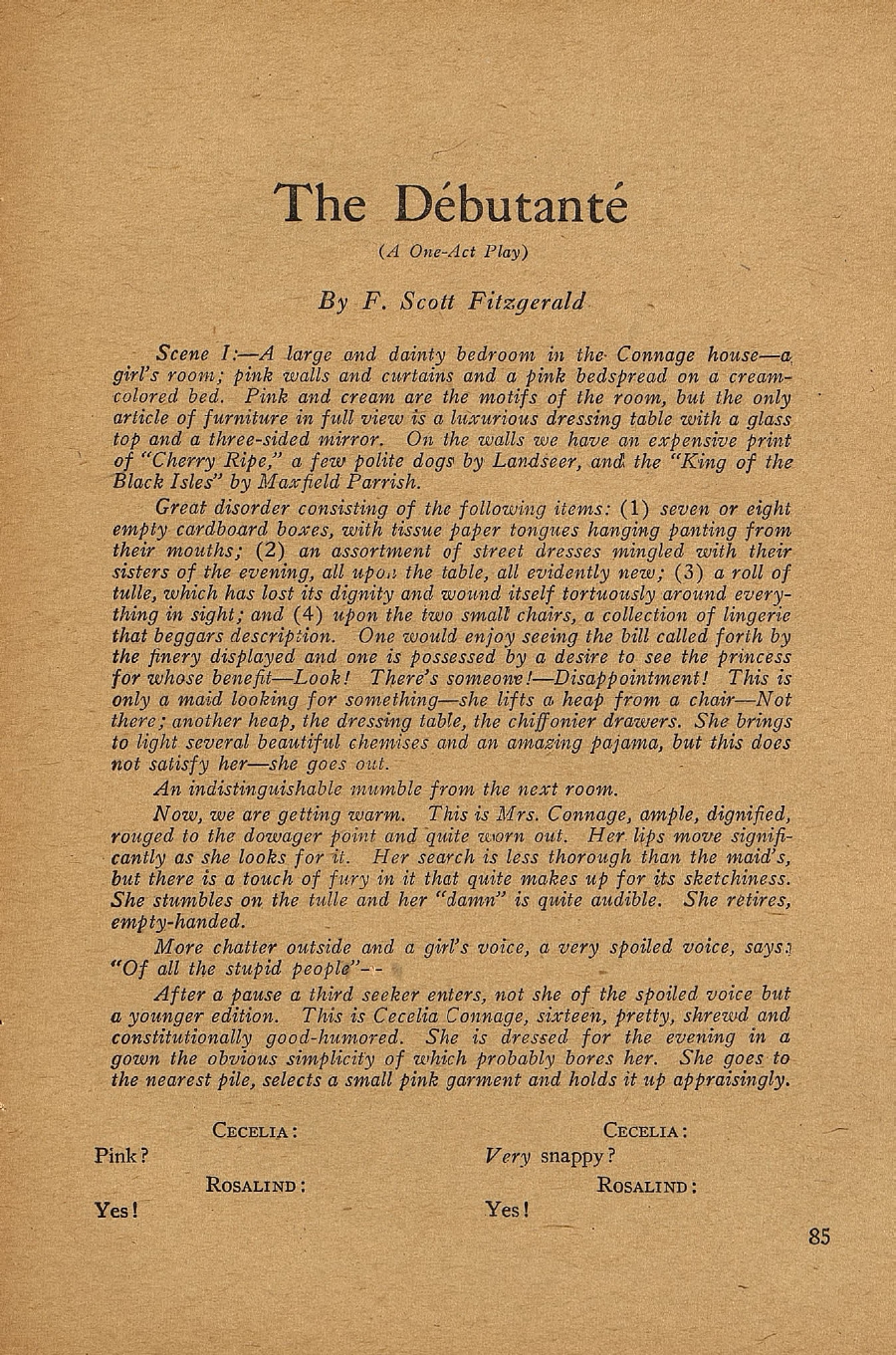

The Débutante (A One-Act Play)

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

SCENE I:—A large and dainty bedroom in the Connage house—a girl’s room; pink walls and curtains and a pink bedspread on a cream-colored bed. Pink and cream are the motifs of the room, but the only article of furniture in full view is a luxurious dressing table with a glass top and a three-sided mirror. On the walls we have an expensive print of “Cherry Ripe,” a few polite dogs by Landseer, and “The Young King of the Black Isles” by Maxfield Parrish.

Great disorder consisting of the following items: (1) seven or eight empty cardboard boxes, with tissue paper tongues handing panting from their mouths; (2) an assortment of street dresses mingled with their sisters of the evening, all upon the table, all evidently new; (3) a roll of tulle, which has lost its dignity and wound itself tortuously around everything in sight; and (4) upon the two small chairs, a collection of lingerie that beggars description. One would enjoy seeing the bill called forth by the finery displayed and one is possessed by a desire to see the princess for whose benefit—Look! There’s someone!—Disappointment! This is only a maid looking for something—she lifts a heap from a chair—Not there; another heap, the dressing table, the chiffonier drawers. She brings to light several beautiful chemises and an amazing pajama, but this does not satisfy her—she goes out.

An indistinguishable mumble from the next room.

Now, we are getting warm. This is MRS. CONNAGE, ample, dignified, rouged to the dowager point and quite worn out. Her lips move significantly as she looks for it. Her search is less thorough than the maid’s, but there is a touch of fury in it that quite makes up for its sketchiness. She stumbles on the tulle and her “damn” is quite audible. She retires empty-handed.

More chatter outside and a girl’s voice, a very spoiled voice, says: “Of all the stupid people”—

After a pause a third seeker enters, not she of the spoiled voice but a younger edition. This is CECELIA Connage, sixteen, pretty, shrewd and constitutionally good-humored. She is dressed for the evening in a gown the obvious simplicity of which probably bores her. She goes to the nearest pile, selects a small pink garment and holds it up appraisingly.

CECELIA: Pink?

ROSALIND: Yes!

CECELIA: Very snappy?

ROSALIND: Yes!

CECELIA: I’ve got it!

(She sees herself in the mirror of the dressing table and commences to tickle-toe on the carpet.)

ROSALIND: (Outside.) What are you doing—trying it on?

(Cecelia ceases and goes out, carrying the garment at the right shoulder. From the other door, enters ALEC Connage, about twenty-three, healthy and quite sure of the cut of his dress clothes. He comes to the center of the room and in a huge voice shouts:)

Mamma!

(There is a chorus of protest from next door and encouraged he starts toward it, but is repelled by another chorus.)

ALEC: So that’s where you all are! Amory Blaine is here.

CECELIA: (Quickly.) Take him down stairs.

ALEC: Oh, he is down stairs.

MRS. CONNAGE: Well, you can show him where his room is. Tell him I’m sorry that I can’t meet him now.

ALEC: He’s heard a lot about you all. I wish you’d hurry. Father’s telling him all about the war and he’s restless. He’s sort of temperamental.

(This last suffices to draw Cecelia into the room.)

CECELIA: (Seating herself high upon lingerie.) How do you mean temperamental?

ALEC: Oh, he writes stuff.

CECELIA: Does he play the piano?

ALEC: I don’t know. He’s sort of ghostly, too—makes you scared to death sometimes—you know, all that artistic business.

CECELIA: (Speculatively.) Drink?

ALEC: Yes—nothing queer about him.

CECELIA: Money?

ALEC: Good Lord—ask him. No, I don’t think so. Still he was at Princeton when I was at New Haven. He must have some.

MRS. CONNAGE: (Enter Mrs. Connage.) Alec, of course, we’re glad to have any friend of yours, but you must admit this is an inconvenient time, and he’ll be a little neglected. This is Rosalind’s week, you see. When a girl comes out she needs all the attention.

ROSALIND: (Outside.) Well, then prove it by coming here and hooking me.

(Exit Mrs. Connage.)

ALEC: Rosalind hasn’t changed a bit.

CECELIA: (In a lower tone.) She’s awfully spoiled.

ALEC: Well, she’ll meet her match tonight.

CECELIA: Who—Mr. Amory Blaine?

(Alec nods.)

Well Rosalind has still to meet the man she can’t out-distance. Honestly, Alec, she treats men terribly. She abuses them and cuts them and breaks dates with them and yawns in their faces—and they come back for more.

ALEC: They love it.

CECELIA: They hate it. She’s a—she’s a sort of vampire, I think—and she can make girls do what she wants usually—only she hates girls.

ALEC: Personality runs in our family.

CECELIA: (Resignedly.) I guess it ran out before it got to me.

ALEC: Does Rosalind behave herself?

CECELIA: Not particularly well. Oh, she’s average—smokes sometimes, drinks punch, frequently kissed—Oh, yes—common knowledge—one of the effects of the war, you know.

(Emerges—Mrs. Connage.)

MRS. CONNAGE: Rosalind’s almost finished and I can go down and meet your friend.

(Exeunt Alec and his mother.)

ROSALIND: (Outside.) Oh, Mother—

CECELIA: Mother’s gone down.

(Rosalind enters, dressed—except for her flowing hair. Rosalind is unquestionably beautiful. A radiant skin with two spots of vanishing color, and a face with one of those eternal mouths, which only one out of every fifty beauties possesses.

It is sensual, slightly, but small and beautifully shaped. If Rosalind had less intelligence her “spoiled” expression might be called a pout, but she seems to have sprung into growth without that immaturity that “pout” suggests. She is wonderfully built, one notices immediately, slender and athletic, yet lacking under-development. Her voice, scarcely musical, has the ghost of an alto quality and is full of vivid instant personality.)

ROSALIND: Honestly, there are only two costumes in the world I really enjoy being in—(combing her hair at the dressing table) a hoop-skirt dress with pantaloons or a bathing suit. I’m quite charming in both of them.

CECELIA: Are you glad you’re coming out?

ROSALIND: Delighted.

CECELIA: (Cynically.) So you can get married and live on Long Island with the fast younger married set? You want life to be a chain of flirtation, with a man for every link.

ROSALIND: Want it to be one!—you mean I’ve found it one.

CECELIA: Ha!

ROSALIND: Cecelia, darling, you don’t know what a trial it is to be—like me—I’ve got to keep my face like steel in the street to keep men from winking at me. If I laugh hard from a front row at the theater, the comedian plays to me for the rest of the evening. If I drop my voice, my eyes, my handkerchief at a dance my partner calls me up on the phone every day for a week.

CECELIA: It must be an awful strain.

ROSALIND: The unfortunate part is that the only men who interest me at all are the totally ineligible ones. Ah—if I were poor, I’d go on the stage. That’s where my type belongs.

CECELIA: Yes, you might as well get paid for the amount of acting you do.

ROSALIND: Sometimes when I’ve felt particularly radiant I’ve thought—why should this be wasted on one man—?

CECELIA: Often when you’re particularly sulky, I’ve wondered why it should all be wasted on just one family.

(Getting up.) I think I’ll go down and meet Mr. Amory Blaine. I like temperamental men.

ROSALIND: My dear girl, there aren’t any. Men don’t know how to be really angry or really happy—and the ones that do go to pieces.

CECELIA: Well, I’m glad I don’t have all your worries. I’m engaged.

ROSALIND: (With a scornful smile.) Engaged? Why you little lunatic. If mother heard you talking like that she’d send you off to boarding school where you belong.

CECELIA: You won’t tell her, though, because I know things I could tell—and you’re too selfish.

ROSALIND: (A little annoyed.) Run along, little girl!—Who are you engaged to, the iceman?—the man that keeps the candy store?

CECELIA: Cheap wit—good-bye, darling, I’ll see you later.

ROSALIND: Oh, be sure and do that—you’re such a help.

(Exit Cecelia. Rosalind finishes her hair and rises, humming. She goes up to the mirror and starts to dance in front of it, on the soft carpet. She watches not her feet, but her eyes—never casually but always intently, even when she smiles.)

(The door suddenly opens and then slams behind a good-looking young man, with a straight, romantic profile, who sees her and melts to instant confusion.)

HE: Oh, I’m sorry, I thought—

SHE: (Smiling radiantly.) Oh, you’re Amory Blaine, aren’t you?

HE: (Regarding her closely.) And you’re Rosalind?

SHE: I’m going to call you Amory—oh, come in—it’s all right—Mother’ll be right in—(under her breath) unfortunately.

HE: (Gazing around.) This is sort of a new wrinkle for me.

SHE: This is No Man’s Land.

HE: This is where you—you— (embarrassment.)

SHE: Yes—all those things.

(She crosses to the bureau.) See, here’s my rouge—eye pencils.

HE: I didn’t know you were that way.

SHE: What did you expect?

HE: I thought you’d be sort of—sort of—sexless; you know, swim and play golf.

SHE: Oh, I do—but not in business hours.

HE: Business?

SHE: Six to two—strictly.

HE: I’d like to have some stock in the corporation.

SHE: Oh, it’s not a corporation—it’s just “Rosalind, Unlimited. ” Fifty-one shares, name, good will and everything goes at $25,000 a year.

HE: (Disapprovingly.) Sort of a chilly proposition.

SHE: Well, Amory, you don’t mind—do you? When I meet a man that doesn’t bore me to death after two weeks, perhaps it’ll be different.

HE: Odd, you have the same point of view on men that I have on women.

SHE: I’m not really feminine, you know—in my mind.

HE: (Interested.) Go on.

SHE: No, you—you go on—you’ve made me talk about myself. That’s against the rules.

HE: Rules?

SHE: My own rules—but you—oh, Amory, I hear you’re brilliant. The family expects so much of you.

HE: How encouraging.

SHE: Alec said you’d taught him to think. Did you? I don’t believe anyone could.

HE: No. I’m really quite dull.

(He evidently doesn’t intend this to be taken quite seriously.)

SHE: Liar.

HE: I’m—I’m religious—I’m literary. I’ve—I’ve even written poems.

SHE: Vers libre—splendid. (She declaims.)

Trees are green,

The birds are singing in the trees,

The girl sips her poison,

The bird flies away; the girl dies.

HE: (Laughing.) No, not that kind.

SHE: (Suddenly.) I like you.

HE: Don’t.

SHE: Modest, too—

HE: I’m afraid of you. I’m always afraid of a girl—until I’ve kissed her.

SHE: (Emphatically.) My dear boy, the war is over.

HE: So I’ll always be afraid of you.

SHE: (Rather sadly.) I suppose you will.

(A slight pause on both their parts.)

HE: (After due consideration.) Listen. This is a frightful thing to ask.

SHE: (Knowing what’s coming.) After five minutes.

HE: But will you—kiss me?—Or are you afraid?

SHE: I’m never afraid—but your reasons are so poor.

HE: Rosalind, I really want to kiss you.

SHE: So do I.

(They kiss—definitely and thoroughly.)

HE: (After a breathless second.) Well, your curiosity is satisfied.

SHE: IS yours?

HE: No, it’s only aroused.

(He looks it.)

SHE: (Dreamily.) I’ve kissed dozens of men. I suppose I’ll kiss dozens more.

HE: (Abstractedly.) Yes, I suppose you could—like that.

SHE: Most people like the way I kiss.

HE: (Remembering himself.) Good Lord, yes. Kiss me once more, Rosalind.

SHE: No—my curiosity is generally satisfied at one.

HE: (Discouraged.) Is that a rule?

SHE: I make rules to fit the cases.

HE: You and I are somewhat alike—except that I’m years older in experience.

SHE: How old are you?

HE: Twenty-three. You?

SHE: Nineteen—just.

HE: I suppose you’re the product of a fashionable school.

SHE: No—I’m fairly raw material. I was expelled from Spence—I’ve forgotten why.

HE: What’s your general trend?

SHE: Oh, I’m bright, quite selfish, emotional when aroused, fond of admiration—

HE: (Suddenly.) I don’t want to fall in love with you—

SHE: (Raising her eyebrows.) Nobody asked you to.

HE: (Continuing calmly)—But I probably will. I love your mouth.

SHE: Hush—please don’t fall in love with my mouth—hair, eyes, shoulders, slippers—but not my mouth. Everybody falls in love with my mouth.

HE: It’s quite beautiful.

SHE: It’s too small.

HE: No, it isn’t—let’s see.

(He kisses her again with the same thoroughness.)

SHE: (Rather moved.) Say something sweet!

HE: (Frightened.) Lord help me.

SHE: (Drawing away.) Well, don’t—if it’s so hard.

HE: Shall we pretend? So soon?

SHE: We haven’t the same standards of time as other people.

HE: Already it’s—other people.

SHE: Let’s pretend.

HE: No—I can’t—it’s sentimental.

SHE: You’re not sentimental?

HE: No, I’m romantic—a sentimental person thinks things will last—a romantic person hopes against hope that they won’t. Sentiment is emotional.

SHE: And you’re not? (with her eyes half closed.) You probably flatter yourself that that’s a superior attitude.

HE: Well—Oh, Rosalind, Rosalind, don’t argue—kiss me again.

SHE: (Quite chilly now.) No—I have no desire to kiss you.

HE: (Openly taken aback.) You wanted to kiss me a minute ago.

SHE: This is now.

HE: I’d better go.

SHE: I suppose so.

(He goes toward the door.)

SHE: Oh!

(He turns.)

SHE: (Laughing.) Score: Home Team, 100—Opponents, Zero.

(He starts back.)

(Quickly.) Rain—no game!

(He goes out.)

(She goes quickly to the chiffonier, takes out a cigarette case and hides it in the side drawer of a desk. Her mother enters—note book in hand.)

MRS. CONNAGE: Good—I’ve been wanting to speak to you alone before we go downstairs.

ROSALIND: Heavens, you frighten me.

MRS. CONNAGE: Rosalind, you’ve been a very expensive proposition.

ROSALIND: (Resignedly.) Yes.

MRS. CONNAGE: And you know your father hasn’t what he once had.

ROSALIND: (Making a wry face.) Oh please don’t talk about money.

MRS. CONNAGE: You can’t do anything without it. This is our last year in this house—and unless things change, Cecelia won’t have the advantages you’ve had.

ROSALIND: (Impatiently.) Well—what is it?

MRS. CONNAGE: So I ask you to please mind me in several things I’ve put down in my note book. The first one is: Don’t disappear with young men. There may be a time when it’s valuable, but at present I want you on the dance floor where I can find you. There are certain men I want to have you meet and I don’t like finding you in some corner of the conservatory exchanging silliness with anyone—or listening to it.

ROSALIND: (Sarcastically.) Yes, listening to it is better.

MRS. CONNAGE: And don’t waste a lot of time with the college set—little boys nineteen and twenty years old. I don’t mind a prom or a football game, but staying away from advantageous parties to eat in little cafes downtown with Tom, Dick and Harry—

ROSALIND: (Offering her code, which is, by the way, quite as high as her mother’s.) Mother, it’s done—one can’t run everything now the way one did in the early nineties.

MRS. CONNAGE: (Paying no attention.) There are several bachelor friends of your father’s that I want you to meet tonight—youngish men.

ROSALIND: (Nodding wisely.) About forty-five?

MRS. CONNAGE: (Sharply.) Why not?

ROSALIND: Oh, quite all right—they know life and are so adorably tired looking—(shakes her head) but they will dance.

MRS. CONNAGE: I haven’t met Mr. Blaine—but I don’t think you’ll care for him. He doesn’t sound like a money maker.

ROSALIND: Mother, I never think about money.

MRS. CONNAGE: You never keep it long enough to think about it.

ROSALIND: (Sighs.) Yes, I suppose some day I’ll marry a ton of it—out of sheer boredom.

MRS. CONNAGE: (Referring to note book.) I had a wire from Hartford. Dawson Ryder is coming up. Now, there’s a young man I like, and he’s floating in money. It seems to me that since you seem tired of Howard Gillespie, you might give Mr. Ryder some encouragement. This is the third time he’s been up in a month.

ROSALIND: How did you know I was tired of Howard Gillespie?

MRS. CONNAGE: The poor boy looks so miserable every time he comes.

ROSALIND: That was one of those romantic pre-battle affairs. They’re all wrong.

MRS. CONNAGE: (Her say said.) At any rate, make us proud of you tonight.

ROSALIND: Don’t you think I’m beautiful?

MRS. CONNAGE: You know you are.

(From downstairs is heard the shriek of a violin being tuned, the rattle of a drum. Mrs. Connage turns quickly to her daughter.)

MRS. CONNAGE: Come.

ROSALIND: One minute.

(Her mother leaves. Rosalind goes to the glass, where she gazes at herself with great satisfaction. She kisses her hand and touches her mirrored mouth with it. Then she turns out the lights and leaves the room.

Silence for a moment. A few chords from the piano, the discreet message of faint drums, the rustle of new silk, all blend on the staircase outside and drift in through the partly opened door. Bundled figures pass in the lighted hall. The laughter heard below becomes doubled and multiplied. Then some one comes in from the side, switches on the lights and closes the door. It is Cecelia. She goes to the chiffonier, looks in the drawers, hesitates—then to the desk whence she takes the cigarette case and selects one. She lights it and puffing and blowing walks toward the mirror.)

CECELIA: (In tremendously sophisticated accents.) Oh, yes, coming out is such a farce nowadays, you know. One really plays around so much before one is seventeen, that it’s positively anticlimax.

(Shaking hands with a visionary, middle-aged nobleman.)

Yes, your grace—I b’lieve I’ve heard my sister speak of you. Have a puff—they’re good. They’re—they’re Coronas. You don’t smoke? What a pity! The King doesn’t allow it, I suppose. Yes, I’ll dance.

(So she dances around the room to a tune from downstairs. Her arms outstretched to an imaginary partner. The cigarette waving in her hand. Darkness comes quickly down and the lights stay low until—)

SCENE II

(Draperies cut off the stage to a corner of a den downstairs, filled by a very comfortable leather lounge. A small light is on each side above and in the middle; over the couch hangs a painting of a very old, very dignified gentleman, period 1860. Outside, the music is heard in a fox trot.

Rosalind is seated on the lounge and on her left is Howard GILLESPIE, a shallow youth of about twenty-four. He is obviously very unhappy and she quite bored.)

GILLESPIE: (Feebly.) What do you mean I’ve changed? I feel the same toward you.

ROSALIND: But you don’t look the same to me.

GILLESPIE: Three weeks ago you used to say that you liked me because I was so blase, so indifferent—I still am.

ROSALIND: But not about me. I used to like you because you had brown eyes and thin legs.

GILLESPIE: (Helplessly.) They’re still thin and brown.

ROSALIND: I used to think you were never jealous. Now you follow me with your eyes wherever I go.

GILLESPIE: I love you.

ROSALIND: (Coldly.) I know it.

GILLESPIE: And you haven’t kissed me for two weeks. I had an idea that after a girl was kissed she was—was—won.

ROSALIND: Those days are over. I have to be won all over again every time you see me.

GILLESPIE: Are you serious?

ROSALIND: About as usual. There used to be two kinds of kisses: First when girls were kissed and deserted, second when they were engaged. Now there’s a third kind where the man is kissed and deserted. If Mr. Jones of the nineties bragged he’d kissed a girl everyone knew he was through with her. If Mr. Jones of 1919 brags the same, everyone knows it’s because he can’t kiss her any more. Given a decent start any girl can beat a man nowadays.

GILLESPIE: Then why do you play with men?

ROSALIND: (Leaning forward confidentially.) For that first moment, when he’s interested. There is a moment—Oh, just before the first kiss, a whispered word—something that makes it worth while.

GILLESPIE: And then?

ROSALIND: Then after that you make him talk about himself. Pretty soon he thinks of nothing but being alone with you.—He sulks, he won’t fight, he doesn’t want to play—Victory.

(Enter Dawson RYDER, twenty-six, handsome, rather cold, wealthy, faithful to his own, a bore perhaps, but steady and sure of success.)

RYDER: I believe this is my dance, Rosalind.

ROSALIND: Very well, Dawson. Mr. Ryder, this is Mr. Gillespie. (They shake hands and Gillespie leaves tremendously downcast.)

RYDER: Your party is certainly a success.

ROSALIND: Is it—I haven’t seen it lately. I’m weary—Do you mind sitting out?

RYDER: Mind—I’m delighted. You know I loath this “rushing” idea. See a girl yesterday, today, tomorrow.

ROSALIND: Dawson!

RYDER: What?

ROSALIND: I wonder if you know you love me.

RYDER: (Startled.) What—Oh—I say, you’re remarkable.

ROSALIND: Because, you know, I’m an awful proposition. Anyone who marries me would have his hands full. I’m mean—mighty mean.

RYDER: Oh, I wouldn’t say that.

ROSALIND: Oh, yes I am—especially to the people nearest me.

(She rises.)

Come, let’s go. I have changed my mind and I want to dance. Mother is probably having a fit.

(They start out.)

Does one shimmy in Hartford?

(Exeunt.)

(Enter Alec and Cecelia.)

CECELIA: Just my luck to get my own brother for an intermission.

ALEC: (Gloomingly.) I’ll go if you want me to.

CECELIA: Good heavens, no—who would I begin the next dance with?

(Sighs.)

There’s no color in a dance since the French officers went back.

ALEC: I hope Amory doesn’t fall in love with Rosalind.

CECELIA: Why, I had an idea you wanted him to.

ALEC: I did, but since seeing these girls—I don’t know. I’m awfully attached to Amory. He’s sensitive and I don’t want him to break his heart over somebody who doesn’t care about him.

CECELIA: He’s very good looking.

ALEC: She won’t marry him, but a girl doesn’t have to marry a man to break his heart.

CECELIA: What does it? I wish I knew the secret.

ALEC: Why, you cold-blooded little kitty. It’s lucky for some that the Lord gave you a pug nose.

(Enter Mrs. Connage.)

MRS. CONNAGE: Where on earth is Rosalind?

ALEC: (Brilliantly.) Of course, you’ve come to the best people to find out. She’d naturally be with us.

MRS. CONNAGE: Her father has marshalled eight bachelor millionaires to meet her.

ALEC: You might form a squad and march through the halls.

MRS. CONNAGE: I’m perfectly serious—for all I know she may be at the Cocoanut Grove with some football player on the night of her debut. You look left and I’ll—

ALEC: (Flippantly.) Hadn’t you better send the butler through the cellar?

MRS. CONNAGE: (Perfectly serious.) Oh, you don’t think she’d be there!

CECELIA: He’s only joking, Mother.

ALEC: Mother had a picture of her tapping a keg of beer with some high hurdler.

MRS. CONNAGE: Let’s look right away.

(They go out. Enter Rosalind with Gillespie.)

GILLESPIE: Rosalind—Once more I ask you. Don’t you care a blessed thing about me?

(Enter AMORY.)

AMORY: My dance.

ROSALIND: Mr. Gillespie, this is Mr. Blaine.

GILLESPIE: I’ve met Mr. Blaine. From Dayton, aren’t you?

AMORY: Yes.

GILLESPIE: (Desperately.) I’ve been there. It’s rather awful.

AMORY: (Spicily.) I don’t know. I always felt that I’d rather be provincial hot-tamale than soup without seasoning.

GILLESPIE: What?

AMORY: Oh, no offense.

(Gillespie bows and leaves.)

ROSALIND: He’s too much people.

AMORY: I was in love with a people once.

ROSALIND: So?

AMORY: Oh yes, some fool—nothing at all to her, except what I read into her.

ROSALIND: What happened?

AMORY: Finally I convinced her that she was smarter than I was—then she threw me over. Said I was impractical, you know.

ROSALIND: What do you mean, impractical?

AMORY: Oh—drive a car, but can’t change a tire.

ROSALIND: What are you going to do?

AMORY: Write—I’m going to start here in New York.

ROSALIND: Greenwich Village.

AMORY: Good heavens, no—I said write—not drink.

ROSALIND: I like business men. Clever men are usually so homely.

AMORY: I feel as if I’d known you ages.

ROSALIND: Oh, are you going to commence the “pyramid” story?

AMORY: No—I was going to make it French. I was Louis 14th and you were one of my—my—(Changing his tone.) Suppose—we fell in love.

ROSALIND: I’ve suggested pretending.

AMORY: If we did, it would be very big.

ROSALIND: Why?

AMORY: Because selfish people are in a way terribly capable of great loves.

ROSALIND: Pretend. (Turning her lips up.) (Very deliberately they kiss.)

AMORY: I can’t say sweet things. But you are beautiful.

ROSALIND: Not that.

AMORY: What then?

ROSALIND: (Sadly.) Oh, nothing—only I want sentiment, real sentiment—and I never find it.

AMORY: I never find anything else in the world—and I loathe it.

ROSALIND: It’s so hard to find a male to gratify one’s artistic taste. (Someone has opened a door and the music of a waltz surges into the room. Rosalind rises.)

ROSALIND: Listen, they’re playing “Kiss Me Again. ” (He looks at her.)

AMORY: Well?

ROSALIND: Well?

AMORY: (Softly—the battle lost.) I love you.

ROSALIND: I love you. (They kiss.)

AMORY: Oh, God, what have I done?

ROSALIND: Nothing. Oh, don’t talk. Kiss me again.

AMORY: I don’t know why or how, but I love you—from the moment I saw you.

ROSALIND: Me, too—I—I—want to belong to you. (Her brother strolls in, starts and then in a loud voice says, “Oh, excuse me, ” and goes.)

ROSALIND: (Her lips scarcely stirring.) Don’t let me go—I don’t care who knows.

AMORY: Say it.

ROSALIND: I love you. (They part.)

ROSALIND: Oh—I am very youthful, thank God—and rather beautiful, thank God—and happy, thank God, thank God—(She pauses and then in an odd burst of frankness adds.) Poor Amory! (He kisses her again.)

CURTAIN.

Note

This is the revised version of the text. The original version was published in the January 1917 issue of the Nassau Literary Magazine. Finally, this piece was incorporated in book 2, chapter 1 of This Side of Paradise.

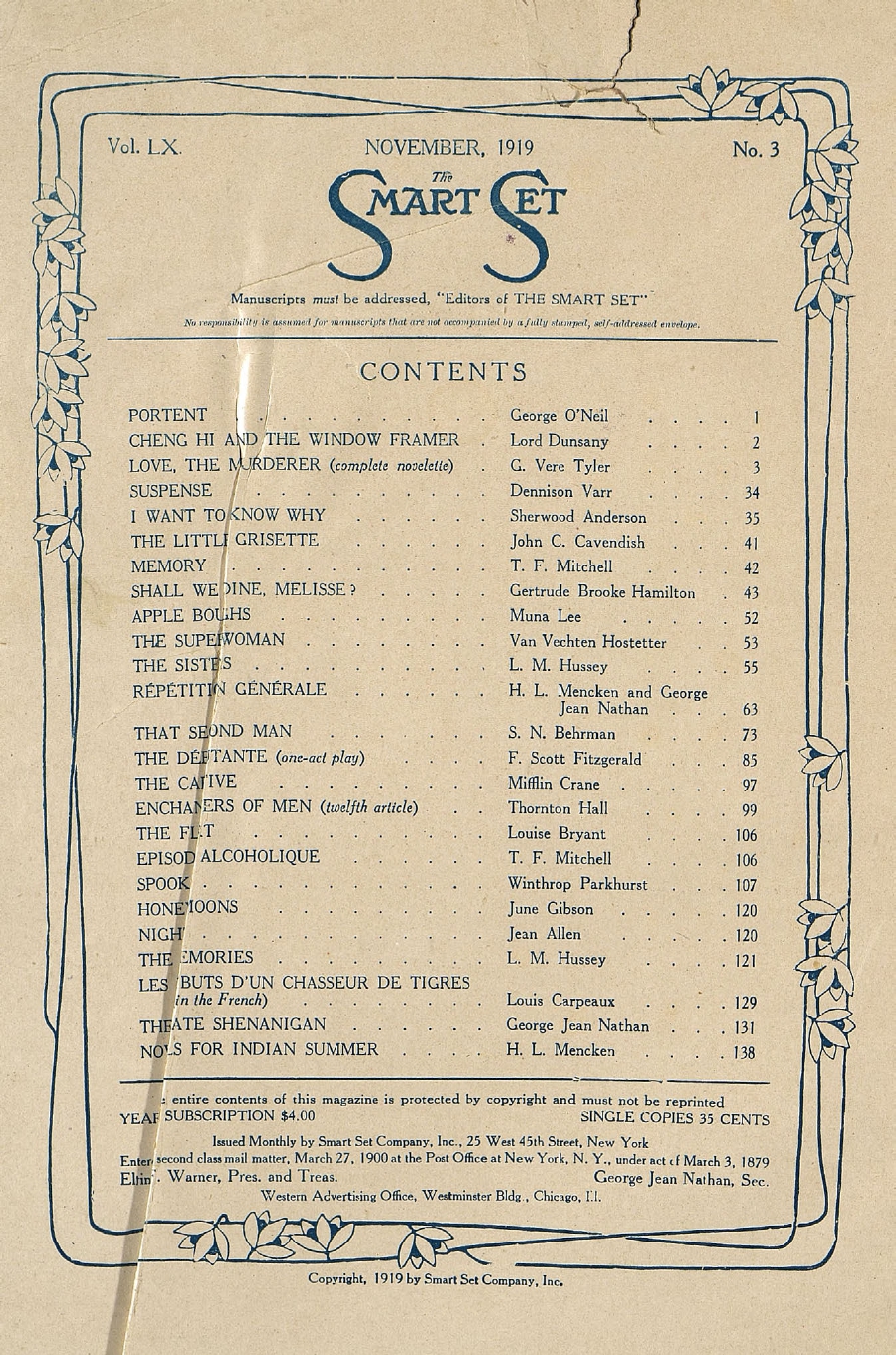

Published in Smart Set magazine (November 1919).

Not illustrated.