Your Way and Mine

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

One spring afternoon in the first year of the present century a young man was experimenting with a new typewriter in a brokerage office on lower Broadway. At his elbow lay an eight-line letter and he was endeavoring to make a copy on the machine but each attempt was marred by a monstrous capital rising unexpectedly in the middle of a word or by the disconcerting intrusion of some symbol such as $ or % into an alphabet whose membership was set at twenty-six many years ago. Whenever he detected a mistake he made a new beginning with a fresh sheet but after the fifteenth try he was aware of a ferocious instinct to cast the machine from the window.

The young man's short blunt fingers were too big for the keys. He was big all over; indeed his bulky body seemed to be in the very process of growth for it had ripped his coat at the back seam, while his trousers clung to thigh and calf like skin tights. His hair was yellow and tousled—you could see the paths of his broad fingers in it—and his eyes were of a hard brilliant blue but the lids drooping a little over them reinforced an impression of lethargy that the clumsy body conveyed. His age was twenty-one.

“What do you think the eraser's for, McComas?”

The young man looked around.

“What's that?” he demanded brusquely.

“The eraser,” repeated the short alert human fox who had come in the outer door and paused behind him. “That there's a good copy except for one word. Use your head or you'll be sitting there until tomorrow.”

The human fox moved on into his private office. The young man sat for a moment, motionless, sluggish. Suddenly he grunted, picked up the eraser referred to and flung it savagely out of the window.

Twenty minutes later he opened the door of his employer's office. In his hand was the letter, immaculately typed, and the addressed envelope.

“Here it is, sir,” he said, frowning a little from his late concentration.

The human fox took it, glanced at it and then looked at McComas with a peculiar smile.

“You didn't use the eraser?”

“No, I didn't, Mr. Woodley.”

“You're one of those thorough young men, aren't you?” said the fox sarcastically.

“What?”

“I said 'thorough' but since you weren't listening I'll change it to 'pig-headed.' Whose time did you waste just to avoid a little erasure that the best typists aren't too proud to make? Did you waste your time or mine?”

“I wanted to make one good copy,” answered McComas steadily.

“You see, I never worked a typewriter before.”

“Answer my question,” snapped Mr. Woodley. “When you sat there making two dozen copies of that letter were you wasting your time or mine?”

“It was mostly my lunch time,” McComas replied, his big face flushing to an angry pink. “I've got to do things my own way or not at all.”

For answer Mr. Woodley picked up the letter and envelope, folded them, tore them once and again and dropped the pieces into the wastepaper basket with a toothy little smile.

“That's my way,” he announced. “What do you think of that?”

Young McComas had taken a step forward as if to snatch the fragments from the fox's hand.

“By golly,” he cried. “By golly. Why, for two cents I'd spank you!”

With an angry snarl Mr. Woodley sprang to his feet, fumbled in his pocket and threw a handful of change upon his desk.

Ten minutes later the outside man coming in to report perceived that neither young McComas nor his hat were in their usual places. But in the private office he found Mr. Woodley, his face crimson and foam bubbling between his teeth, shouting frantically into the telephone. The outside man noticed to his surprise that Mr. Woodley was in daring dishabille and that there were six suspender buttons scattered upon the office floor.

In 1902 Henry McComas weighed 196 pounds. In 1905 when he journeyed back to his home town, Elmira, to marry the love of his boyhood he tipped accurate beams at 210. His weight remained constant for two years but after the panic of 1907 it bounded to 220, about which comfortable figure it was apparently to hover for the rest of his life.

He looked mature beyond his years—under certain illuminations his yellow hair became a dignified white—and his bulk added to the impression of authority that he gave. During his first five years off the farm there was never a time when he wasn't scheming to get into business for himself.

For a temperament like Henry McComas', which insisted on running at a pace of its own, independence was an utter necessity. He must make his own rules, willy-nilly, even though he join the ranks of those many abject failures who have also tried. Just one week after he had achieved his emancipation from other people's hierarchies he was moved to expound his point to Theodore Drinkwater, his partner—this because Drinkwater had wondered aloud if he intended never to come downtown before eleven.

“I doubt it,” said McComas.

“What's the idea?” demanded Drinkwater indignantly. “What do you think the effect's going to be on our office force?”

“Does Miss Johnston show any sign of being demoralized?”

“I mean after we get more people. It isn't as if you were an old man, Mac, with your work behind you. You're only twenty-eight, not a day older than I. What'll you do at forty?”

“I'll be downtown at eleven o'clock,” said McComas, “every working day of my life.”

Later in the week one of their first clients invited them to lunch at a celebrated business club; the club's least member was a rajah of the swelling, expanding empire.

“Look around, Ted,” whispered McComas as they left the dining-room. “There's a man looks like a prize-fighter, and there's one who looks like a ham actor. That's a plumber there behind you; there's a coal heaver and a couple of cowboys—do you see? There's a chronic invalid and a confidence man, a pawn-broker—that one on the right. By golly, where are all the big business men we came to see?”

The route back to their office took them by a small restaurant where the clerks of the district flocked to lunch.

“Take a look at them, Ted, and you'll find the men who know the rules—and think and act and look like just what they are.”

“I suppose if they put on pink mustaches and came to work at five in the afternoon they'd get to be great men,” scoffed Drinkwater.

“Posing is exactly what I don't mean. Just accept yourself. We're brought up on fairy stories about the new leaf, but who goes on believing them except those who have to believe and have to hope or else go crazy. I think America will be a happier country when the individual begins to look his personal limitations in the face. Anything that's in your character at twenty-one is usually there to stay.”

In any case what was in Henry McComas' was there to stay. Henry McComas wouldn't dine with a client in a bad restaurant for a proposition of three figures, wouldn't hurry his luncheon for a proposition of four, wouldn't go without it for a proposition of five. And in spite of these peculiarities the exporting firm in which he owned forty-nine per cent of the stock began to pepper South America with locomotives, dynamos, barb wire, hydraulic engines, cranes, mining machinery, and other appurtenances of civilization. In 1913 when Henry McComas was thirty-four he owned a house on Ninety-second Street and calculated that his income for the next year would come to thirty thousand dollars. And because of a sudden and unexpected demand from Europe which was not for pink lemonade, it came to twice that. The buying agent for the British Government arrived, followed by the buying agents for the French, Belgian, Russian and Serbian Governments, and a share of the commodities required were assembled under the stewardship of Drinkwater and McComas. There was a chance that they would be rich men. Then suddenly this eventually began to turn on the woman Henry McComas had married.

Stella McComas was the daughter of a small hay and grain dealer of upper New York. Her father was unlucky and always on the verge of failure, so she grew up in the shadow of worry. Later, while Henry McComas got his start in New York, she earned her living by teaching physical culture in the public schools of Utica. In consequence she brought to her marriage a belief in certain stringent rules for the care of the body and an exaggerated fear of adversity.

For the first years she was so impressed with her husband's rapid rise and so absorbed in her babies that she accepted Henry as something infallible and protective, outside the scope of her provincial wisdom. But as her little girl grew into short dresses and hair ribbons, and her little boy into the custody of an English nurse she had more time to look closely at her husband. His leisurely ways, his corpulency, his sometimes maddening deliberateness, ceased to be the privileged idiosyncrasies of success, and became only facts.

For a while he paid no great attention to her little suggestions as to his diet, her occasional crankiness as to his hours, her invidious comparisons between his habits and the fancied habits of other men. Then one morning a peculiar lack of taste in his coffee precipitated the matter into the light.

“I can't drink the stuff—it hasn't had any taste for a week,” he complained. “And why is it brought in a cup from the kitchen? I like to put the cream and sugar in myself.”

Stella avoided an answer but later he reverted to the matter.

“About my coffee. You'll remember—won't you?—to tell Rose.”

Suddenly she smiled at him innocently.

“Don't you feel better, Henry?” she asked eagerly.

“What?”

“Less tired, less worried?”

“Who said I was tired and worried? I never felt better in my life.”

“There you are.” She looked at him triumphantly. “You laugh at my theories but this time you'll have to admit there's something in them. You feel better because you haven't had sugar in your coffee for over a week.”

He looked at her incredulously.

“What have I had?”

“Saccharine.”

He got up indignantly and threw his newspaper on the table.

“I might have known it,” he broke out. “All that bringing it out from the kitchen. What the devil is saccharine?”

“It's a substitute, for people who have a tendency to run to fat.”

For a moment he hovered on the edge of anger, then he sat down shaking with laughter.

“It's done you good,” she said reproachfully.

“Well, it won't do me good any more,” he said grimly. “I'm thirty-four years old and I haven't been sick a day in ten years. I've forgotten more about my constitution than you'll ever know.”

“You don't live a healthy life, Henry. It's after forty that things begin to tell.”

“Saccharine!” he exclaimed, again breaking into laughter. “Saccharine! I thought perhaps it was something to keep me from drink. You know they have these—”

Suddenly she grew angry.

“Well why not? You ought to be ashamed to be so fat at your age. You wouldn't be if you took a little exercise and didn't lie around in bed all morning.”

Words utterly failed her,

“If I wanted to be a farmer,” said her husband quietly, “I wouldn't have left home. This saccharine business is over today—do you see?”

Their financial situation rapidly improved. By the second year of the war they were keeping a limousine and chauffeur and began to talk vaguely of a nice summer house on Long Island Sound. Month by month a swelling stream of materials flowed through the ledgers of Drinkwater and McComas to be dumped on the insatiable bonfire across the ocean. Their staff of clerks tripled and the atmosphere of the office was so charged with energy and achievement that Stella herself often liked to wander in on some pretext during the afternoon.

One day early in 1916 she called to learn that Mr. McComas was out and was on the point of leaving when she ran into Ted Drinkwater coming out of the elevator.

“Why, Stella,” he exclaimed, “I was thinking about you only this morning.”

The Drinkwaters and the McComases were close if not particularly spontaneous friends. Nothing but their husbands' intimate association would have thrown the two women together, yet they were “Henry, Ted, Mollie, and Stella” to each other and in ten years scarcely a month had passed without their partaking in a superficially cordial family dinner. The dinner being over, each couple indulged in an unsparing post-mortem over the other without, however, any sense of disloyalty. They were used to each other—so Stella was somewhat surprised by Ted Drinkwater's personal eagerness at meeting her this afternoon.

“I want to see you,” he said in his intent direct way. “Have you got a minute, Stella? Could you come into my office?”

“Why, yes.”

As they walked between rows of typists toward the glassed privacy of THEODORE DRINKWATER, PRESIDENT, Stella could not help thinking that he made a more appropriate business figure than her husband. He was lean, terse, quick. His eye glanced keenly from right to left as if taking the exact measure of every clerk and stenographer in sight.

“Sit down, Stella.”

She waited, a feeling of vague apprehension stealing over her.

Drinkwater frowned.

“It's about Henry,” he said.

“Is he sick?” she demanded quickly.

“No. Nothing like that.” He hesitated. “Stella, I've always thought you were a woman with a lot of common sense.”

She waited.

“This is a thing that's been on my mind for over a year,” he continued. “He and I have battled it out so often that—that a certain coldness has grown up between us.”

“Yes?” Stella's eyes blinked nervously.

“It's about the business,” said Drinkwater abruptly. “A coldness with a business partner is a mighty unpleasant thing.”

“What's the matter?”

“The old story, Stella. These are big years for us and he thinks business is going to wait while he carries on in the old country-store way. Down at eleven, hour and a half for lunch, won't be nice to a man he doesn't like for love or money. In the last six months he's lost us about three sizable orders by things like that.”

Instinctively she sprang to her husband's defense.

“But hasn't he saved money too by going slow? On that thing about the copper, you wanted to sign right away and Henry—”

“Oh, that—” He waved it aside a little hurriedly. “I'm the last man to deny that Henry has a wonderful instinct in certain ways—”

“But it was a great big thing,” she interrupted, “It would have practically ruined you if he hadn't put his foot down. He said—”

She pulled herself up short.

“Oh, I don't know,” said Drinkwater with an expression of annoyance, “perhaps not so bad as that. Anyway, we all make mistakes and that's aside from the question. We have the opportunity right now of jumping into Class A. I mean it. Another two years of this kind of business and we can each put away our first million dollars. And, Stella, whatever happens, I am determined to put away mine. Even—” He considered his words for a moment. “Even if it comes to breaking with Henry.”

“Oh!” Stella exclaimed. “I hope—”

“I hope not too. That's why I wanted to talk to you. Can't you do something, Stella? You're about the only person he'll listen to. He's so darn pig-headed he can't understand how he disorganizes the office. Get him up in the morning. No man ought to lie in bed till eleven.”

“He gets up at half past nine.”

“He's down here at eleven. That's what counts. Stir him up. Tell him you want more money. Orders are more money and there are lots of orders around for anyone who goes after them.”

“I'll see what I can do,” she said anxiously. “But I don't know— Henry's difficult—very set in his ways.”

“You'll think of something. You might—” He smiled grimly. “You might give him a few more bills to pay. Sometimes I think an extravagant wife's the best inspiration a man can have. We need more pep down here. I've got to be the pep for two. I mean it, Stella, I can't carry this thing alone.”

Stella left the office with her mind in a panic. All the fears and uncertainties of her childhood had been brought suddenly to the surface. She saw Henry cast off by Ted Drinkwater and trying unsuccessfully to run a business of his own. With his easy-going ways! They would slide down hill, giving up the servants one by one, the car, the house. Before she reached home her imagination had envisaged poverty, her children at work—starvation. Hadn't Ted Drinkwater just told her that he himself was the life of the concern— that he kept things moving? What would Henry do alone?

For a week she brooded over the matter, guarding her secret but looking with a mixture of annoyance and compassion at Henry over the dinner table. Then she mustered up her resolution. She went to a real estate agent and handed over her entire bank account of nine thousand dollars as the first payment on a house they had fearfully coveted on Long Island. . . . That night she told Henry.

“Why, Stella, you must have gone crazy,” he cried aghast. “You must have gone crazy. Why didn't you ask me?”

He wanted to take her by the shoulders and shake her.

“I was afraid, Henry,” she answered truthfully.

He thrust his hands despairingly through his yellow hair.

“Just at this time, Stella. I've just taken out an insurance policy that's more than I can really afford—we haven't paid for the new car—we've had a new front put on this house—last week your sable coat. I was going to devote tonight to figuring just how close we were running on money.”

“But can't you—can't you take something out of the business until things get better?” she demanded in alarm.

“That's just what I can't do. It's impossible. I can't explain because you don't understand the situation down there. You see Ted and I—can't agree on certain things—”

Suddenly a new light dawned on her and she felt her body flinch. Supposing that by bringing about this situation she had put her husband into his partner's hands. Yet wasn't that what she wanted— wasn't it necessary for the present that Henry should conform to Drinkwater's methods?

“Sixty thousand dollars,” repeated Henry in a frightened voice that made her want to cry. “I don't know where I am going to get enough to buy it on mortgage.” He sank into a chair. “I might go and see the people you dealt with tomorrow and make a compromise—let some of your nine thousand go.”

“I don't think they would,” she said, her face set. “They were awfully anxious to sell—the owner's going away.”

She had acted on impulse, she said, thinking that in their increasing prosperity the money would be available. He had been so generous about the new car—she supposed that now at last they could afford what they wanted.

It was typical of McComas that after the first moment of surprise he wasted no energy in reproaches. But two days later he came home from work with such a heavy and dispirited look on his face that she could not help but guess that he and Ted Drinkwater had had it out— and that what she wanted had come true. That night in shame and pity she cried herself to sleep.

A new routine was inaugurated in Henry McComas' life. Each morning Stella woke him at eight and he lay for fifteen minutes in an unwilling trance, as if his body were surprised at this departure from the custom of a decade. He reached the office at nine-thirty as promptly as he had once reached it at eleven—on the first morning his appearance caused a flutter of astonishment among the older employees—and he limited his lunch time to a conscientious hour. No longer could he be found asleep on his office couch between two and three o'clock on summer afternoons—the couch itself vanished into that limbo which held his leisurely periods of digestion and his cherished surfeit of sleep. These were his concessions to Drinkwater in exchange for the withdrawal of sufficient money to cover his immediate needs.

Drinkwater of course could have bought him out, but for various reasons the senior partner did not consider this advisable. One of them, though he didn't admit it to himself, was his absolute reliance on McComas in all matters of initiative and decision. Another reason was the tumultuous condition of the market, for as 1916 boomed on with the tragic battle of the Somme the allied agents sailed once more to the city of plenty for the wherewithal of another year. Coincidently Drinkwater and McComas moved into a suite that was like a floor in a country club and there they sat all day while anxious and gesticulating strangers explained what they must have, helplessly pledging their peoples to thirty years of economic depression. Drinkwater and McComas farmed out a dozen contracts a week and started the movement of countless tons toward Europe. Their names were known up and down the Street now—they had forgotten what it was to be kept waiting on a telephone.

But though profits increased and Stella, settled in the Long Island house, seemed for the first time in years perfectly satisfied, Henry McComas found himself growing irritable and nervous. What he missed most was the sleep for which his body hungered and which seemed to descend upon him at its richest just as he was shocked back into the living world each morning. And in spite of all material gains he was always aware that he was walking in his own paths no longer.

Their interests broadened and Drinkwater was frequently away on trips to the industrial towns of New England or the South. In consequence the detail of the office fell upon McComas—and he took it hard. A man capable of enormous concentration, he had previously harvested his power for hours of importance. Now he was inclined to fritter it away upon things that in perspective often proved to be inessentials. Sometimes he was engaged in office routine until six, then at home working until midnight when he tumbled, worn out but often still wide-eyed, into his beleaguered bed.

The firm's policy was to slight their smaller accounts in Cuba and the West Indies and concentrate upon the tempting business of the war, and all through the summer they were hurrying to clear the scenes for the arrival of a new purchasing commission in September. When it arrived it unexpectedly found Drinkwater in Pennsylvania, temporarily out of reach. Time was short and the orders were to be placed in bulk. After much anxious parley over the telephone McComas persuaded four members of the commission to meet him for an hour at his own house that night.

Thanks to his own foresight everything was in order. If he hadn't been able to be specific over the phone the coup toward which he had been working would have ended in failure. When it was brought off he was due for a rest and he knew it acutely. He'd had sharp fierce headaches in the past few weeks—he had never known a headache before.

The commissioners had been indefinite as to what time he could expect them that night. They were engaged for dinner and would be free somewhere between nine and eleven. McComas reached home at six, rested for a half hour in a steaming bath and then stretched himself gratefully on his bed. Tomorrow he would join Stella and the children in the country. His week-ends had been too infrequent in this long summer of living alone in the Ninety-second Street house with a deaf housekeeper. Ted Drinkwater would have nothing to say now, for this deal, the most ambitious of all, was his own. He had originated and engineered it—it seemed as if fate had arranged Drinkwater's absence in order to give him the opportunity of concluding it himself.

He was hungry. He considered whether to take cold chicken and buttered toast at the hands of the housekeeper or to dress and go out to the little restaurant on the corner. Idly he reached his hand toward the bell, abandoned the attempt in the air, overcome by a pleasing languor which dispelled the headache that had bothered him all day.

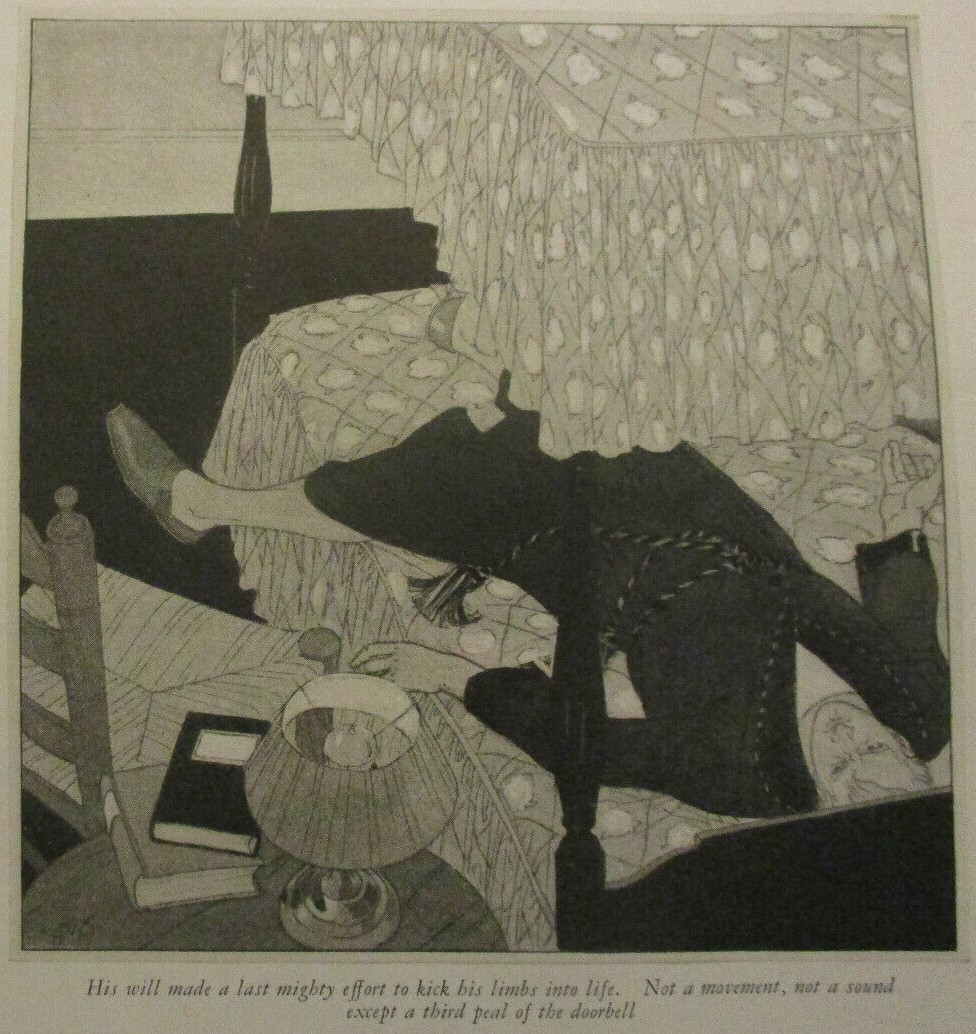

That reminded him to take some aspirin and as he got up to go toward the bureau he was surprised at the weakened condition in which the hot bath had left him. After a step or two he turned about suddenly and plunged rather than fell back upon the bed. A faint feeling of worry passed over him and then an iron belt seemed to wind itself around his head and tighten, sending a spasm of pain through his body. He would ring for Mrs. Corcoran, who would call a doctor to fix him up. In a moment he would reach up his hand to the bell beside his bed. In a minute—he wondered at his indecision—then he cried out sharply as he realized the cause of it. His will had already given his brain the order and his brain had signaled it to his hand. It was his hand that would not obey.

He looked at his hand. Rather white, relaxed, motionless, it lay upon the counterpane. Again he gave it a command, felt his neck cords tighten with the effort. It did not move.

“It's asleep,” he thought, but with rising alarm. “It'll pass off in a minute.”

Then he tried to reach his other hand across his body to massage away the numbness but the other hand remained with a sort of crazy indifference on its own side of the bed. He tried to lift his foot—his knees…

After a few seconds he gave a snort of nervous laughter. There was something ridiculous about not being able to move your own foot. It was like someone else's foot, a foot in a dream. For a moment he had the fantastic notion that he must be asleep. But no—the unmistakable sense of reality was in the room.

“This is the end,” he thought, without fear, almost without emotion. “This thing, whatever it is, is creeping over me. In a minute I shall be dead.”

But the minute passed and another minute, and nothing happened, nothing moved except the hand of the little leather clock on his dresser which crept slowly over the point of seven minutes to seven. He turned his head quickly from side to side, shaking it as a runner kicks his legs to warm up. But there was no answering response from the rest of his body, only a slight rise and fall between belly and chest as he breathed out and in and a faint tremble of his helpless limbs from the faint tremble of the bed.

“Help!” he called out, “Mrs. Corcoran. Mrs. Cor-cor-an, help! Mrs. Corcor—”

There was no answer. She was in the kitchen probably. No way of calling her except by the bell, two feet over his head. Nothing to do but lie there until this passed off, or until he died, or until someone inquired for him at the front door.

The clock ticked past nine o'clock. In a house two blocks away the four members of the commission finished dinner, looked at their watches and issued forth into the September night with brief-cases in their hands. Outside a private detective nodded and took his place beside the chauffeur in the waiting limousine. One of the men gave an address on Ninety-second Street.

Ten minutes later Henry McComas heard the doorbell ring through the house. If Mrs. Corcoran was in the kitchen she would hear it too. On the contrary if she was in her room with the door shut she would hear nothing.

He waited, listening intently for the sound of footsteps. A minute passed. Two minutes. The doorbell rang again.

“Mrs. Corcoran!” he cried desperately.

Sweat began to roll from his forehead and down the folds of his neck. Again he shook his head desperately from side to side, and his will made a last mighty effort to kick his limbs into life. Not a movement, not a sound, except a third peal of the bell, impatient and sustained this time and singing like a trumpet of doom in his ear.

Suddenly he began to swear at the top of his voice calling in turn upon Mrs. Corcoran, upon the men in the street, asking them to break down the door, reassuring, imprecating, explaining. When he finished, the bell had stopped ringing; there was silence once more within the house.

A few minutes later the four men outside reentered their limousine and drove south and west toward the docks. They were to sleep on board ship that night. They worked late for there were papers to go ashore but long after the last of them was asleep Henry McComas lay awake and felt the sweat rolling from his neck and forehead. Perhaps all his body was sweating. He couldn't tell.

For a year and a half Henry McComas lay silent in hushed and darkened rooms and fought his way back to life. Stella listened while a famous specialist explained that certain nervous systems were so constituted that only the individual could judge what was, or wasn't, a strain. The specialist realized that a host of hypochondriacs imposed upon this fact to nurse and pamper themselves through life when in reality they were as hardy and phlegmatic as the policeman on the corner, but it was nevertheless a fact. Henry McComas' large, lazy body had been the protection and insulation of a nervous intensity as fine and taut as a hair wire. With proper rest it functioned brilliantly for three or four hours a day—fatigued ever so slightly over the danger line it snapped like a straw.

Stella listened, her face wan and white. Then a few weeks later she went to Ted Drinkwater's office and told him what the specialist had said. Drinkwater frowned uncomfortably—he remarked that specialists were paid to invent consoling nonsense. He was sorry but business must go on, and he thought it best for everyone, including Henry, that the partnership be dissolved. He didn't blame Henry but he couldn't forget that just because his partner didn't see fit to keep in good condition they had missed the opportunity of a lifetime.

After a year Henry McComas found one day that he could move his arms down to the wrists; from that hour onward he grew rapidly well. In 1919 he went into business for himself with very little except his abilities and his good name and by the time this story ends, in 1926, his name alone was good for several million dollars.

What follows is another story. There are different people in it and it takes place when Henry McComas' personal problems are more or less satisfactorily solved; yet it belongs to what has gone before. It concerns Henry McComas' daughter.

Honoria was nineteen, with her father's yellow hair (and, in the current fashion, not much more of it), her mother's small pointed chin and eyes that she might have invented herself, deep-set yellow eyes with short stiff eyelashes that sprang from them like the emanations from a star in a picture. Her figure was slight and childish and when she smiled you were afraid that she might expose the loss of some baby teeth, but the teeth were there, a complete set, little and white. Many men had looked upon Honoria in flower. She expected to be married in the fall.

Whom to marry was another matter. There was a young man who traveled incessantly back and forth between London and Chicago playing in golf tournaments. If she married him she would at least be sure of seeing her husband every time he passed through New York. There was Max Van Camp who was unreliable, she thought, but good-looking in a brisk sketchy way. There was a dark man named Strangler who played polo and would probably beat her with a riding crop like the heroes of Ethel M. Dell. And there was Russel Codman, her father's right-hand man, who had a future and whom she liked best of all.

He was not unlike her father in many ways—slow in thought, leisurely and inclined to stoutness—and perhaps these qualities had first brought him to Henry McComas' favor. He had a genial manner and a hearty confident smile, and he had made up his mind about Honoria when he first saw her stroll into her father's office one day three years before. But so far he hadn't asked her to marry him, and though this annoyed Honoria she liked him for it too—he wanted to be secure and successful before he asked her to share his life. Max Van Camp, on the other hand, had asked her a dozen times. He was a quick-witted “alive” young man of the new school, continually bubbling over with schemes that never got beyond McComas' waste-paper basket—one of those curious vagabonds of business who drift from position to position like strolling minstrels and yet manage to keep moving in an upward direction all their lives. He had appeared in McComas' office the year before bearing an introductory letter from a friend.

He got the position. For a long while neither he nor his employer, nor anyone in the office, was quite sure what the position was. McComas at that time was interested in exporting, in real estate developments and, as a venture, in the possibilities of carrying the chain store idea into new fields.

Van Camp wrote advertising, investigated properties and accomplished such vague duties as might come under the phrase, “We'll get Van Camp to do that.” He gave the effect always of putting much more clamor and energy into a thing than it required and there were those who, because he was somewhat flashy and often wasted himself like an unemployed dynamo, called him a bluff and pronounced that he was usually wrong.

“What's the matter with you young fellows?” Henry McComas said to him one day. “You seem to think business is some sort of trick game, discovered about 1910, that nobody ever heard of before. You can't even look at a proposition unless you put it into this new language of your own. What do you mean you want to 'sell' me this proposition? Do you want to suggest it—or are you asking money for it?”

“Just a figure of speech, Mr. McComas.”

“Well, don't fool yourself that it's anything else. Business sense is just common sense with your personal resources behind it—nothing more.”

“I've heard Mr. Codman say that,” agreed Max Van Camp meekly.

“He's probably right. See here—” he looked keenly at Van Camp; “how would you like a little competition with that same gentleman? I'll put up a bonus of five hundred dollars on who comes in ahead.”

“I'd like nothing better, Mr. McComas.”

“All right. Now listen. We've got retail hardware stores in every city of over a thousand population in Ohio and Indiana. Some fellow named McTeague is horning in on the idea—he's taken the towns of twenty thousand and now he's got a chain as long as mine. I want to fight him in the towns of that size. Codman's gone to Ohio. Suppose you take Indiana. Stay six weeks. Go to every town of over twenty thousand in the state and buy up the best hardware stores in sight.”

“Suppose I can only get the second-best?”

“Do what you can. There isn't any time to waste because McTeague's got a good start on us. Think you can leave tonight?”

He gave some further instructions while Van Camp fidgeted impatiently. His mind had grasped what was required of him and he wanted to get away. He wanted to ask Honoria McComas one more question, the same one, before it was time to go.

He received the same answer because Honoria knew she was going to marry Russel Codman, just as soon as he asked her to. Sometimes when she was alone with Codman she would shiver with excitement, feeling that now surely the time had come at last—in a moment the words would flow romantically from his lips. What the words would be she didn't know, couldn't imagine, but they would be thrilling and extraordinary, not like the spontaneous appeals of Max Van Camp which she knew by heart.

She waited excitedly for Russel Codman's return from the West. This time, unless he spoke, she would speak herself. Perhaps he didn't want her after all, perhaps there was someone else. In that case she would marry Max Van Camp and make him miserable by letting him see that he was getting only the remnants of a blighted life.

Then before she knew it the six weeks were up and Russel Codman came back to New York. He reported to her father that he was going to see her that night. In her excitement Honoria found excuses for being near the front door. The bell rang finally and a maid stepped past her and admitted a visitor into the hall.

“Max,” she cried.

He came toward her and she saw that his face was tired and white.

“Will you marry me?” he demanded without preliminaries.

She sighed.

“How many times, Max?”

“I've lost count,” he said cheerfully. “But I haven't even begun. Do I understand that you refuse?”

“Yes, I'm sorry.”

“Waiting for Codman?”

She grew annoyed.

“That's not your affair.”

“Where's your father?”

She pointed, not deigning to reply.

Max entered the library where McComas rose to meet him.

“Well?” inquired the older man. “How did you make out?”

“How did Codman make out?” demanded Van Camp.

“Codman did well. He bought about eighteen stores—in several cases the very stores McTeague was after.”

“I knew he would,” said Van Camp.

“I hope you did the same.”

“No,” said Van Camp unhappily. “I failed.”

“What happened?” McComas slouched his big body reflectively back in his chair and waited.

“I saw it was no use,” said Van Camp after a moment. “I don't know what sort of places Codman picked up in Ohio but if it was anything like Indiana they weren't worth buying. These towns of twenty thousand haven't got three good hardware stores. They've got one man who won't sell out on account of the local wholesaler; then mere's one man that McTeague's got, and after that only little places on the corner. Anything else you'll have to build up yourself. I saw right away that it wasn't worth while.” He broke off. “How many places did Codman buy?”

“Eighteen or nineteen.”

“I bought three.”

McComas looked at him impatiently.

“How did you spend your time?” he asked. “Take you two weeks apiece to get them?”

“Took me two days,” said Van Camp gloomily. “Then I had an idea.”

“What was that?” McComas' voice was ironical.

“Well—McTeague had all the good stores.”

“Yes.”

“So I thought the best thing was to buy McTeague's company over his head.”

“What?”

“Buy his company over his head,” and Van Camp added with seeming irrelevance, “you see, I heard that he'd had a big quarrel with his uncle who owned fifteen per cent of the stock.”

“Yes,” McComas was leaning forward now—the sarcasm gone from his face.

“McTeague only owned twenty-five per cent and the storekeepers themselves owned forty. So if I could bring round the uncle we'd have a majority. First I convinced the uncle that his money would be safer with McTeague as a branch manager in our organization—”

“Wait a minute—wait a minute,” said McComas. “You go too fast for me. You say the uncle had fifteen per cent—how'd you get the other forty?”

“From the owners. I told them the uncle had lost faith in McTeague and I offered them better terms. I had all their proxies on condition that they would be voted in a majority only.”

“Yes,” said McComas eagerly. Then he hesitated. “But it didn't work, you say. What was the matter with it? Not sound?”

“Oh, it was a sound scheme all right.”

“Sound schemes always work.”

“This one didn't.”

“Why not?”

“The uncle died.”

McComas laughed. Then he stopped suddenly and considered.

“So you tried to buy McTeague's company over his head?”

“Yes,” said Max with a shamed look. “And I failed.”

The door flew open suddenly and Honoria rushed into the room.

“Father,” she cried. At the sight of Max she stopped, hesitated, and then carried away by her excitement continued:

“Father—did you ever tell Russel how you proposed to Mother?”

“Why, let me see—yes, I think I did.”

Honoria groaned.

“Well, he tried to use it again on me.”

“What do you mean?”

“All these months I've been waiting—” she was almost in tears, “waiting to hear what he'd say. And then—when it came—it sounded familiar—as if I'd heard it before.”

“It's probably one of my proposals,” suggested Van Camp. “I've used so many.”

She turned on him quickly.

“Do you mean to say you've ever proposed to any other girl but me?”

“Honoria—would you mind?”

“Mind. Of course I wouldn't mind. I'd never speak to you again as long as I lived.”

“You say Codman proposed to you in the words I used to your mother?” demanded McComas.

“Exactly,” she wailed. “He knew them by heart.”

“That's the trouble with him,” said McComas thoughtfully. “He always was my man and not his own. You'd better marry Max, here.”

“Why—” she looked from one to the other, “why—I never knew you liked Max, Father. You never showed it.”

“Well, that's just the difference,” said her father, “between your way and mine.”

Notes

The story was written in February 1926 at Salies-de-Bearn, a spa in the French Pyrenees where the Fitzgeralds spent two months while Zelda was taking a cure for digestive problems. In his cover letter Fitzgerald informed Harold Ober: «This is one of the lowsiest stories I've ever written. Just terrible! I lost interest in the middle (by the way the last part is typed triple space because I thought I could fix it—but I couldn't). Please—and I mean this—don't offer it to the Post. I think that as things are now it would be wretched policy. Nor to the Red Book. It hasn't one redeeming touch of my usual spirit in it. I was desparate to begin a story + invented a business plot—the kind I can't handle. I'd rather have $1000 for it from some obscure place than twice that + have it seen. I feel very strongly about this!».

Published in Woman's Home Companion magazine (May 1927).

Illustrations by Frederick Chapman.

The story was syndicated by the Metro Newspaper Service and re-published: for example, in The Sunday Pioneer Press Magazine (St. Paul, MN) (August 28, 1927).