Diamond Dick and the First Law of Woman

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

When Diana Dickey came back from France in the spring of 1919, her parents considered that she had atoned for her nefarious past. She had served a year in the Red Cross and she was presumably engaged to a young American ace of position and charm. They could ask no more; of Diana’s former sins only her nickname survived——

Diamond Dick!—she had selected it herself, of all the names in the world, when she was a thin, black-eyed child of ten.

“Diamond Dick,” she would insist, “that’s my name. Anybody that won’t call me that’s a double darn fool.”

“But that’s not a nice name for a little lady,” objected her governess. “If you want to have a boy’s name why don’t you call yourself George Washington?”

“Because my name’s Diamond Dick,” explained Diana patiently. “Can’t you understand? I got to be named that because if I don’t I’ll have a fit and upset the family, see?”

She ended by having the fit—a fine frenzy that brought a disgusted nerve specialist out from New York—and the nickname too. And once in possession she set about modeling her facial expression on that of a butcher boy who delivered meats at Greenwich back doors. She stuck out her lower jaw and parted her lips on one side, exposing sections of her first teeth—and from this alarming aperture there issued the harsh voice of one far gone in crime.

“Miss Caruthers,” she would sneer crisply, “what’s the idea of no jam? Do you wanta whack the side of the head?”

“Diana! I’m going to call your mother this minute!”

“Look at here!” threatened Diana darkly. “If you call her you’re liable to get a bullet the side of the head.”

Miss Caruthers raised her hand uneasily to her bangs. She was somewhat awed.

“Very well,” she said uncertainly, “if you want to act like a little ragamuffin——”

Diana did want to. The evolutions which she practiced daily on the sidewalk and which were thought by the neighbors to be some new form of hop-scotch were in reality the preliminary work on an Apache slouch. When it was perfected, Diana lurched forth into the streets of Greenwich, her face violently distorted and half obliterated by her father’s slouch hat, her body reeling from side to side, jerked hither and yon by the shoulders, until to look at her long was to feel a faint dizziness rising to the brain.

At first it was merely absurd, but when Diana’s conversation commenced to glow with weird rococo phrases, which she imagined to be the dialect of the underworld, it became alarming. And a few years later she further complicated the problem by turning into a beauty—a dark little beauty with tragedy eyes and a rich voice stirring in her throat.

Then America entered the war and Diana on her eighteenth birthday sailed with a canteen unit to France.

The past was over; all was forgotten. Just before the armistice was signed, she was cited in orders for coolness under fire. And—this was the part that particularly pleased her mother—it was rumored that she was engaged to be married to Mr. Charley Abbot of Boston and Bar Harbor, “a young aviator of position and charm.”

But Mrs. Dickey was scarcely prepared for the changed Diana who landed in New York. Seated in the limousine bound for Greenwich, she turned to her daughter with astonishment in her eyes.

“Why, everybody’s proud of you, Diana,” she cried, “the house is simply bursting with flowers. Think of all you’ve seen and done, at nineteen!”

Diana’s face, under an incomparable saffron hat, stared out into Fifth Avenue, gay with banners for the returning divisions.

“The war’s over,” she said in a curious voice, as if it had just occurred to her this minute.

“Yes,” agreed her mother cheerfully, “and we won. I knew we would all the time.”

She wondered how to best introduce the subject of Mr. Abbot.

“You’re quieter,” she began tentatively. “You look as if you were more ready to settle down.”

“I want to come out this fall.”

“But I thought——” Mrs. Dickey stopped and coughed—“Rumors had led me to believe——”

“Well, go on, Mother. What did you hear?”

“It came to my ears that you were engaged to that young Charles Abbot.”

Diana did not answer and her mother licked nervously at her veil. The silence in the car became oppressive. Mrs. Dickey had always stood somewhat in awe of Diana—and she began to wonder if she had gone too far.

“The Abbots are such nice people in Boston,” she ventured uneasily. “I’ve met his mother several times—she told me how devoted——”

“Mother!” Diana’s voice, cold as ice, broke in upon her loquacious dream. “I don’t care what you heard or where you heard it, but I’m not engaged to Charley Abbot. And please don’t ever mention the subject to me again.”

In November Diana made her debut in the ball room of the Ritz. There was a touch of irony in this “introduction to life”—for at nineteen Diana had seen more of reality, of courage and terror and pain, than all the pompous dowagers who peopled the artificial world.

But she was young and the artificial world was redolent of orchids and pleasant, cheerful snobbery and orchestras which set the rhythm of the year, summing up the sadness and suggestiveness of life in new tunes. All night the saxophones wailed the hopeless comment of the “Beale Street Blues,” while five hundred pairs of gold and silver slippers shuffled the shining dust. At the gray tea hour there were always rooms that throbbed incessantly with this low sweet fever, while fresh faces drifted here and there like rose petals blown by the sad horns around the floor.

In the center of this twilight universe Diana moved with the season, keeping half a dozen dates a day with half a dozen men, drowsing asleep at dawn with the beads and chiffon of an evening dress tangled among dying orchids on the floor beside her bed.

The year melted into summer. The flapper craze startled New York, and skirts went absurdly high and the sad orchestras played new tunes. For a while Diana’s beauty seemed to embody this new fashion as once it had seemed to embody the higher excitement of the war; but it was noticeable that she encouraged no lovers, that for all her popularity her name never became identified with that of any one man. She had had a hundred “chances,” but when she felt that an interest was becoming an infatuation she was at pains to end it once and for all.

A second year dissolved into long dancing nights and swimming trips to the warm south. The flapper movement scattered to the winds and was forgotten; skirts tumbled precipitously to the floor and there were fresh songs from the saxophones for a new crop of girls. Most of those with whom she had come out were married now—some of them had babies. But Diana, in a changing world, danced on to newer tunes.

With a third year it was hard to look at her fresh and lovely face and realize that she had once been in the war. To the young generation it was already a shadowy event that had absorbed their older brothers in the dim past—ages ago. And Diana felt that when its last echoes had finally died away her youth, too, would be over. It was only occasionally now that anyone called her “Diamond Dick.” When it happened, as it did sometimes, a curious, puzzled expression would come into her eyes as though she could never connect the two pieces of her life that were broken sharply asunder.

Then, when five years had passed, a brokerage house failed in Boston and Charley Abbot, the war hero, came back from Paris, wrecked and broken by drink and with scarcely a penny to his name.

***

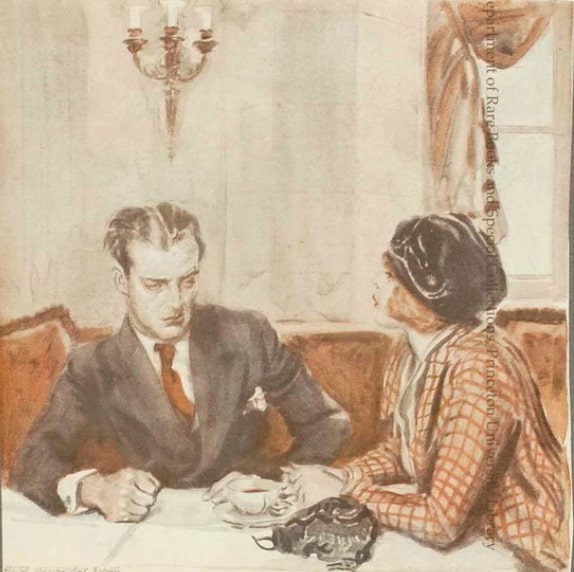

Diana saw him first at the Restaurant Mont Mihiel, sitting at a side table with a plump, indiscriminate blonde from the half-world. She excused herself unceremoniously to her escort and made her way toward him. He looked up as she approached and she felt a sudden faintness, for he was worn to a shadow and his eyes, large and dark like her own, were burning in red rims of fire.

“Why, Charley——”

He got drunkenly to his feet and they shook hands in a dazed way. He murmured an introduction, but the girl at the table evinced her displeasure at the meeting by glaring at Diana with cold blue eyes.

“Why, Charley——” said Diana again, “you’ve come home, haven’t you.”

“I’m here for good.”

“I want to see you, Charley. I—I want to see you as soon as possible. Will you come out to the country tomorrow?”

“Tomorrow?” He glanced with an apologetic expression at the blonde girl. “I’ve got a date. Don’t know about tomorrow. Maybe later in the week——”

“Break your date.”

His companion had been drumming with her fingers on the cloth and looking restlessly around the room. At this remark she wheeled sharply back to the table.

“Charley,” she ejaculated, with a significant frown.

“Yes, I know,” he said to her cheerfully, and turned to Diana. “I can’t make it tomorrow. I’ve got a date.”

“It’s absolutely necessary that I see you tomorrow,” went on Diana ruthlessly. “Stop looking at me in that idiotic way and say you’ll come out to Greenwich.”

“What’s the idea?” cried the other girl in a slightly raised voice. “Why don’t you stay at your own table? You must be tight.”

“Now Elaine!” said Charley, turning to her reprovingly.

“I’ll meet the train that gets to Greenwich at six,” Diana went on coolly. “If you can’t get rid of this—this woman——” she indicated his companion with a careless wave of her hand—”send her to the movies.”

With an exclamation the other girl got to her feet and for a moment a scene was imminent. But nodding to Charley, Diana turned from the table, beckoned to her escort across the room and left the cafe.

“I don’t like her,” cried Elaine querulously when Diana was out of hearing. “Who is she anyhow? Some old girl of yours?”

“That’s right,” he answered, frowning. “Old girl of mine. In fact, my only old girl.”

“Oh, you’ve known her all your life.”

“No.” He shook his head. “When I first met her she was a canteen worker in the war.”

“She was!” Elaine raised her brows in surprise. “Why she doesn’t look——”

“Oh, she’s not nineteen any more—she’s nearly twenty-five.” He laughed. “I saw her sitting on a box at an ammunition dump near Soissons one day with enough lieutenants around her to officer a regiment. Three weeks after that we were engaged!”

“Then what?” demanded Elaine sharply.

“Usual thing,” he answered with a touch of bitterness. “She broke it off. Only unusual part of it was that I never knew why. Said good-by to her one day and left for my squadron. I must have said something or done something then that started the big fuss. I’ll never know. In fact I don’t remember anything about it very clearly because a few hours later I had a crash and what happened just before has always been damn dim in my head. As soon as I was well enough to care about anything I saw that the situation was changed. Thought at first that there must be another man.”

“Did she break the engagement?”

“She cern’ly did. While I was getting better she used to sit by my bed for hours looking at me with the funniest expression in her eyes. Finally I asked for a mirror—I thought I must be all cut up or something. But I wasn’t. Then one day she began to cry. She said she’d been thinking it over and perhaps it was a mistake and all that sort of thing. Seemed to be referring to some quarrel we’d had when we said good-by just before I got hurt. But I was still a pretty sick man and the whole thing didn’t seem to make any sense unless there was another man in it somewhere. She said that we both wanted our freedom, and then she looked at me as if she expected me to make some explanation or apology—and I couldn’t think what I’d done. I remember leaning back in the bed and wishing I could die right then and there. Two months later I heard she’d sailed for home.”

Elaine leaned anxiously over the table.

“Don’t go to the country with her, Charley,” she said. “Please don’t go. She wants you back—I can tell by looking at her.”

He shook his head and laughed.

“Yes she does,” insisted Elaine, “I can tell. I hate her. She had you once and now she wants you back. I can see it in her eyes. I wish you’d stay in New York with me.”

“No,” he said stubbornly. “Going out and look her over. Diamond Dick’s an old girl of mine.”

***

Diana was standing on the station platform in the late afternoon, drenched with golden light. In the face of her immaculate freshness Charley Abbot felt ragged and old. He was only twenty-nine, but four wild years had left many lines around his dark, handsome eyes. Even his walk was tired—it was no longer a demonstration of fitness and physical grace. It was a way of getting somewhere, failing other forms of locomotion; that was all.

“Charley,” Diana cried, “where’s your bag?”

“I only came out to dinner—I can’t possibly spend the night.”

He was sober, she saw, but he looked as if he needed a drink badly. She took his arm and guided him to a red-wheeled coupe parked in the street.

“Get in and sit down,” she commanded. “You walk as if you were about to fall down anyhow.”

“Never felt better in my life.”

She laughed scornfully.

“Why do you have to get back tonight?” she demanded.

“I promised—you see I had an engagement——”

“Oh, let her wait!” exclaimed Diana impatiently. “She didn’t look as if she had much else to do. Who is she anyhow?”

“I don’t see how that could possibly interest you, Diamond Dick.”

She flushed at the familiar name.

“Everything about you interests me. Who is that girl?”

“Elaine Russel. She’s in the movies—sort of.”

“She looked pulpy,” said Diana thoughtfully. “I keep thinking of her. You look pulpy too. What are you doing with yourself—waiting for another war?”

They turned into the drive of a big rambling house on the Sound. Canvas was being stretched for dancing on the lawn.

“Look!” She was pointing at a figure in knickerbockers on a side veranda. “That’s my brother Breck. You’ve never met him. He’s home from New Haven for the Easter holidays and he’s having a dance tonight.”

A handsome boy of eighteen came down the veranda steps toward them.

“He thinks you’re the greatest man in the world,” whispered Diana. “Pretend you’re wonderful.”

There was an embarrassed introduction.

“Done any flying lately?” asked Breck immediately.

“Not for some years,” admitted Charley.

“I was too young for the war myself,” said Breck regretfully, “but I’m going to try for a pilot’s license this summer. It’s the only thing, isn’t it—flying I mean.”

“Why, I suppose so,” said Charley somewhat puzzled. “I hear you’re having a dance tonight.”

Breck waved his hand carelessly.

“Oh, just a lot of people from around here. I should think anything like that’d bore you to death—after all you’ve seen.”

Charley turned helplessly to Diana.

“Come on,” she said, laughing, “we’ll go inside.”

Mrs. Dickey met them in the hall and subjected Charley to a polite but somewhat breathless scrutiny. The whole household seemed to treat him with unusual respect, and the subject had a tendency to drift immediately to the war.

“What are you doing now?” asked Mr. Dickey. “Going into your father’s business?”

“There isn’t any business left,” said Charley frankly. “I’m just about on my own.”

Mr. Dickey considered for a moment.

“If you haven’t made any plans why don’t you come down and see me at my office some day this week. I’ve got a little proposition that may interest you.”

It annoyed Charley to think that Diana had probably arranged all this. He needed no charity. He had not been crippled, and the war was over five years. People did not talk like this any more.

The whole first floor had been set with tables for the supper that would follow the dance, so Charley and Diana had dinner with Mr. and Mrs. Dickey in the library upstairs. It was an uncomfortable meal at which Mr. Dickey did the talking and Diana covered up the gaps with nervous gaiety. He was glad when it was over and he was standing with Diana on the veranda in the gathering darkness.

“Charley——” She leaned close to him and touched his arm gently. “Don’t go to New York tonight. Spend a few days down here with me. I want to talk to you and I don’t feel that I can talk tonight with this party going on.”

“I’ll come out again—later in the week,” he said evasively.

“Why not stay tonight?”

“I promised I’d be back at eleven.”

“At eleven?” She looked at him reproachfully. “Do you have to account to that girl for your evenings?”

“I like her,” he said defiantly. “I’m not a child, Diamond Dick, and I rather resent your attitude. I thought you closed out your interest in my life five years ago.”

“You won’t stay?”

“No.”

“All right—then we only have an hour. Let’s walk out and sit on the wall by the Sound.”

Side by side they started through the deep twilight where the air was heavy with salt and roses.

“Do you remember the last time we walked somewhere together?” she whispered.

“Why—no. I don’t think I do. Where was it?”

“It doesn’t matter—if you’ve forgotten.”

When they reached the shore she swung herself up on the low wall that skirted the water.

“It’s spring, Charley.”

“Another spring.”

“No—just spring. If you say ‘another spring’ it means you’re getting old.” She hesitated. “Charley——”

“Yes, Diamond Dick.”

“I’ve been waiting to talk to you like this for five years.”

Looking at him out of the comer of her eye she saw he was frowning and changed her tone.

“What kind of work are you going into, Charley?”

“I don’t know. I’ve got a little money left and I won’t have to do anything for awhile. I don’t seem to fit into business very well.”

“You mean like you fitted into the war.”

“Yes.” He turned to her with a spark of interest. “I belonged to the war. It seems a funny thing to say but I think I’ll always look back to those days as the happiest in my life.”

“I know what you mean,” she said slowly. “Nothing quite so intense or so dramatic will ever happen to our generation again.”

They were silent for a moment. When he spoke again his voice was trembling a little.

“There are things lost in it—parts of me—that I can look for and never find. It was my war in a way, you see, and you can’t quite hate what was your own.” He turned to her suddenly. “Let’s be frank, Diamond Dick—we loved each other once and it seems—seems rather silly to be stalling this way with you.”

She caught her breath.

“Yes,” she said faintly, “let’s be frank.”

“I know what you’re up to and I know you’re doing it to be kind. But life doesn’t start all over again when a man talks to an old love on a spring night.”

“I’m not doing it to be kind.”

He looked at her closely.

“You lie, Diamond Dick. But—even if you loved me now it wouldn’t matter. I’m not like I was five years ago—I’m a different person, can’t you see? I’d rather have a drink this minute than all the moonlight in the world. I don’t even think I could love a girl like you any more.”

She nodded.

“I see.”

“Why wouldn’t you marry me five years ago, Diamond Dick?”

“I don’t know,” she said after a minute’s hesitation, “I was wrong.”

“Wrong!” he exclaimed bitterly. “You talk as if it had been guesswork, like betting on white or red.”

“No, it wasn’t guesswork.”

There was a silence for a minute—then she turned to him with shining eyes.

“Won’t you kiss me, Charley?” she asked simply.

He started.

“Would it be so hard to do?” she went on. “I’ve never asked a man to kiss me before.”

With an exclamation he jumped off the wall.

“I’m going to the city,” he said.

“Am I—such bad company as all that?”

“Diana.” He came close to her and put his arms around her knees and looked into her eyes. “You know that if I kiss you I’ll have to stay. I’m afraid of you—afraid of your kindness, afraid to remember anything about you at all. And I couldn’t go from a kiss of yours to—another girl.”

“Good-by,” she said suddenly.

He hesitated for a moment then he protested helplessly.

“You put me in a terrible position.”

“Good-by.”

“Listen Diana——”

“Please go away.”

He turned and walked quickly toward the house.

Diana sat without moving while the night breeze made cool puffs and ruffles on her chiffon dress. The moon had risen higher now, and floating in the Sound was a triangle of silver scales, trembling a little to the stiff, tinny drip of the banjos on the lawn.

Alone at last—she was alone at last. There was not even a ghost left now to drift with through the years. She might stretch out her arms as far as they could reach into the night without fear that they would brush friendly cloth. The thin silver had worn off from all the stars.

She sat there for almost an hour, her eyes fixed upon the points of light on the other shore. Then the wind ran cold fingers along her silk stockings so she jumped off the wall, landing softly among the bright pebbles of the sand. .

“Diana!”

Breck was coming toward her, flushed with the excitement of his party.

“Diana! I want you to meet a man in my class at New Haven. His brother took you to a prom three years ago.”

She shook her head.

“I’ve got a headache; I’m going upstairs.”

Coming closer Breck saw that her eyes were glittering with tears.

“Diana, what’s the matter?”

“Nothing.”

“Something’s the matter.”

“Nothing, Breck. But oh, take care, take care! Be careful who you love.”

“Are you in love with—Charley Abbot?”

She gave a strange, hard little laugh.

“Me? Oh, God, no, Breck! I don’t love anybody. I wasn’t made for anything like love. I don’t even love myself any more. It was you I was talking about. That was advice, don’t you understand?”

She ran suddenly toward the house, holding her skirts high out of the dew. Reaching her own room she kicked off her slippers and threw herself on the bed in the darkness.

“I should have been careful,” she whispered to herself. “All my life I’ll be punished for not being more careful. I wrapped all my love up like a box of candy and gave it away.”

Her window was open and outside on the lawn the sad, dissonant horns were telling a melancholy story. A blackamoor was two-timing the lady to whom he had pledged faith. The lady warned him, in so many words, to stop fooling ‘round Sweet Jelly-Roll, even though Sweet Jelly-Roll was the color of pale cinnamon——

The phone on the table by her bed rang imperatively. Diana took up the receiver.

“Yes.”

“One minute please, New York calling.”

It flashed through Diana’s head that it was Charley—but that was impossible. He must be still on the train.

“Hello.” A woman was speaking. “Is this the Dickey residence?”

“Yes.”

“Well, is Mr. Charles Abbot there?”

Diana’s heart seemed to stop beating as she recognized the voice—it was the blonde girl of the cafe.

“What?” she asked dazedly.

“I would like to speak to Mr. Abbot at once please.”

“You—you can’t speak to him. He’s gone.”

There was a pause. Then the girl’s voice, suspiciously:

“He isn’t gone.”

Diana’s hands tightened on the telephone.

“I know who’s talking,” went on the voice, rising to a hysterical note, “and I want to speak to Mr. Abbot. If you’re not telling the truth, and he finds out, there’ll be trouble.”

“Be quiet!”

“If he’s gone, where did he go?”

“I don’t know.”

“If he isn’t at my apartment in half an hour I’ll know you’re lying and I’ll——”

Diana hung up the receiver and tumbled back on the bed—too weary of life to think or care. Out on the lawn the orchestra was singing and the words drifted in her window on the breeze.

Lis-sen while I—get you tole:

Stop foolin’ ‘roun’ sweet—Jelly-Roll——

She listened. The Negro voices were wild and loud—life was in that key, so harsh a key. How abominably helpless she was! Her appeal was ghostly, impotent, absurd, before the barbaric urgency of this other girl’s desire.

Just treat me pretty, just treat me sweet

Cause I possess a fo’ty-fo’ that don’t repeat.

The music sank to a weird, threatening minor. It reminded her of something—some mood in her own childhood—and a new atmosphere seemed to open up around her. It was not so much a definite memory as it was a current, a tide setting through her whole body.

Diana jumped suddenly to her feet and groped for her slippers in the darkness. The song was beating in her head and her little teeth set together in a click. She could feel the tense golf-muscles rippling and tightening along her arms.

Running into the hall she opened the door to her father’s room, closed it cautiously behind her and went to the bureau. It was in the top drawer—black and shining among the pale anaemic collars. Her hand closed around the grip and she drew out the bullet clip with steady fingers. There were five shots in it.

Back in her room she called the garage.

“I want my roadster at the side entrance right away!”

Wriggling hurriedly out of her evening dress to the sound of breaking snaps she let it drop in a soft pile on the floor, replacing it with a golf sweater, a checked sport-skirt and an old blue and white blazer which she pinned at the collar with a diamond bar. Then she pulled a tam-o-shanter over her dark hair and looked once in the mirror before turning out the light.

“Come on, Diamond Dick!” she whispered aloud.

With a short exclamation she plunged the automatic into her blazer pocket and hurried from the room.

***

Diamond Dick! The name had jumped out at her once from a lurid cover, symbolizing her childish revolt against the softness of life. Diamond Dick was a law unto himself, making his own judgments with his back against the wall. If justice was slow he vaulted into his saddle and was off for the foothills, for in the unvarying tightness of his instincts he was higher and harder than the law. She had seen in him a sort of deity, infinitely resourceful, infinitely just. And the commandment he laid down for himself in the cheap, ill-written pages was first and foremost to keep what was his own.

An hour and a half from the time when she had left Greenwich, Diana pulled up her roadster in front of the Restaurant Mont Mihiel. The theaters were already dumping their crowds into Broadway and half a dozen couples in evening dress looked at her curiously as she slouched through the door. A moment later she was talking to the head waiter.

“Do you know a girl named Elaine Russel?”

“Yes, Miss Dickey. She comes here quite often.”

“I wonder if you can tell me where she lives.”

The head waiter considered.

“Find out,” she said sharply, “I’m in a hurry.”

He bowed. Diana had come there many times with many men. She had never asked him a favor before.

His eyes roved hurriedly around the room.

“Sit down,” he said.

“I’m all right. You hurry.”

He crossed the room and whispered to a man at a table—in a minute he was back with the address, an apartment on 49th Street.

In her car again she looked at her wrist watch—it was almost midnight, the appropriate hour. A feeling of romance, of desperate and dangerous adventure thrilled her, seemed to flow out of the electric signs and the rushing cabs and the high stars. Perhaps she was only one out of a hundred people bound on such an adventure tonight—for her there had been nothing like this since the war.

Skidding the corner into East 49th Street she scanned the apartments on both sides. There it was—“The Elkson”—a wide mouth of forbidding yellow light. In the hall a Negro elevator boy asked her name.

“Tell her it’s a girl with a package from the moving picture company.”

He worked a plug noisily.

“Miss Russel? There’s a lady here says she’s got a package from the moving picture company.”

A pause.

“That’s what she says… All right.” He turned to Diana. “She wasn’t expecting no package but you can bring it up.” He looked at her, frowned suddenly. “You ain’t got no package.”

Without answering she walked into the elevator and he followed, shoving the gate closed with maddening languor…

“First door to your right.”

She waited until the elevator door had started down again. Then she knocked, her fingers tightening on the automatic in her blazer pocket.

Running footsteps, a laugh; the door swung open and Diana stepped quickly into the room.

It was a small apartment, bedroom, bath and kitchenette, furnished in pink and white and heavy with last week’s smoke. Elaine Russel had opened the door herself. She was dressed to go out and a green evening cape was over her arm. Charley Abbot sipping at a highball was stretched out in the room’s only easy chair.

“What is it?” cried Elaine quickly.

With a sharp movement Diana slammed the door behind her and Elaine stepped back, her mouth falling ajar.

“Good evening,” said Diana coldly, and then a line from a forgotten nickel novel flashed into her head, “I hope I don’t intrude.”

“What do you want?” demanded Elaine. “You’ve got your nerve to come butting in here!”

Charley who had not said a word set down his glass heavily on the arm of the chair. The two girls looked at each other with unwavering eyes.

“Excuse me,” said Diana slowly, “but I think you’ve got my man.”

“I thought you were supposed to be a lady!” cried Elaine in rising anger. “What do you mean by forcing your way into this room?”

“I mean business. I’ve come for Charley Abbot.”

Elaine gasped.

“Why, you must be crazy!”

“On the contrary, I’ve never been so sane in my life. I came here to get something that belongs to me.”

Charley uttered an exclamation but with a simultaneous gesture the two women waved him silent.

“All right,” cried Elaine, “we’ll settle this right now.”

“I’ll settle it myself,” said Diana sharply. “There’s no question or argument about it. Under other circumstances I might feel a certain pity for you—in this case you happen to be in my way. What is there between you two? Has he promised to marry you?”

“That’s none of your business!”

“You’d better answer,” Diana warned her.

“I won’t answer.”

Diana took a sudden step forward, drew back her arm and with all the strength in her slim hard muscles, hit Elaine a smashing blow in the cheek with her open hand.

Elaine staggered up against the wall. Charley uttered an exclamation and sprang forward to find himself looking into the muzzle of a forty-four held in a small determined hand.

“Help!” cried Elaine wildly. “Oh, she’s hurt me! She’s hurt me!”

“Shut up!” Diana’s voice was hard as steel. “You’re not hurt. You’re just pulpy and soft. But if you start to raise a row I’ll pump you full of tin as sure as you’re alive. Sit down! Both of you. Sit down!”

Elaine sat down quickly, her face pale under her rouge. After an instant’s hesitation Charley sank down again into his chair.

“Now,” went on Diana, waving the gun in a constant arc that included them both. “I guess you know I’m in a serious mood. Understand this first of all. As far as I’m concerned neither of you have any rights whatsoever and I’d kill you both rather than leave this room without getting what I came for. I asked if he’d promised to marry you.”

“Yes,” said Elaine sullenly.

The gun moved toward Charley.

“Is that so?”

He licked his lips, nodded.

“My God!” said Diana in contempt. “And you admit it. Oh, it’s funny, it’s absurd—if I didn’t care so much I’d laugh.”

“Look here!” muttered Charley, “I’m not going to stand much of this, you know.”

“Yes you are! You’re soft enough to stand anything now.” She turned to the girl, who was trembling. “Have you any letters of his?”

Elaine shook her head.

“You lie,” said Diana. “Go and get them! I’ll give you three. One——”

Elaine rose nervously and went into the other room. Diana edged along the table, keeping her constantly in sight.

“Hurry!”

Elaine returned with a small package in her hand which Diana took and slipped into her blazer pocket.

“Thanks. You had ‘em all carefully preserved I see. Sit down again and we’ll have a little talk.”

Elaine sat down. Charley drained off his whisky and soda and leaned back stupidly in his chair.

“Now,” said Diana, “I’m going to tell you a little story. It’s about a girl who went to a war once and met a man who she thought was the finest and bravest man she had ever known. She fell in love with him and he with her and all the other men she had ever known became like pale shadows compared with this man that she loved. But one day he was shot down out of the air, and when he woke up into the world he’d changed. He didn’t know it himself but he’d forgotten things and become a different man. The girl felt sad about this—she saw that she wasn’t necessary to him any more, so there was nothing to do but say good-by.

“So she went away and every night for a while she cried herself to sleep but he never came back to her and five years went by. Finally word came to her that this same injury that had come between them was ruining his life. He didn’t remember anything important any more—how proud and fine he had once been, and what dreams he had once had. And then the girl knew that she had the right to try and save what was left of his life because she was the only one who knew all the things he’d forgotten. But it was too late. She couldn’t approach him any more—she wasn’t coarse enough and gross enough to reach him now—he’d forgotten so much.

“So she took a revolver, very much like this one here, and she came after this man to the apartment of a poor, weak, harmless rat of a girl who had him in tow. She was going to either bring him to himself—or go back to the dust with him where nothing would matter any more.”

She paused. Elaine shifted uneasily in her chair. Charley was leaning forward with his face in his hands.

“Charley!”

The word, sharp and distinct, startled him. He dropped his hands and looked up at her.

“Charley!” she repeated in a thin clear voice. “Do you remember Fontenay in the late fall?”

A bewildered look passed over his face.

“Listen, Charley. Pay attention. Listen to every word I say. Do you remember the poplar trees at twilight, and a long column of French infantry going through the town? You had on your blue uniform, Charley, with the little numbers on the tabs and you were going to the front in an hour. Try and remember, Charley!”

He passed his hand over his eyes and gave a funny little sigh. Elaine sat bolt upright in her chair and gazed from one to the other of them with wide eyes.

“Do you remember the poplar trees?” went on Diana. “The sun was going down and the leaves were silver and there was a bell ringing. Do you remember, Charley? Do you remember?”

Again silence. Charley gave a curious little groan and lifted his head.

“I can’t—understand,” he muttered hoarsely. “There’s something funny here.”

“Can’t you remember?” cried Diana. The tears were streaming from her eyes. “Oh God! Can’t you remember? The brown road and the poplar trees and the yellow sky.” She sprang suddenly to her feet. “Can’t you remember?” she cried wildly. “Think, think—there’s time. The bells are ringing—the bells are ringing, Charley! And there’s just one hour!”

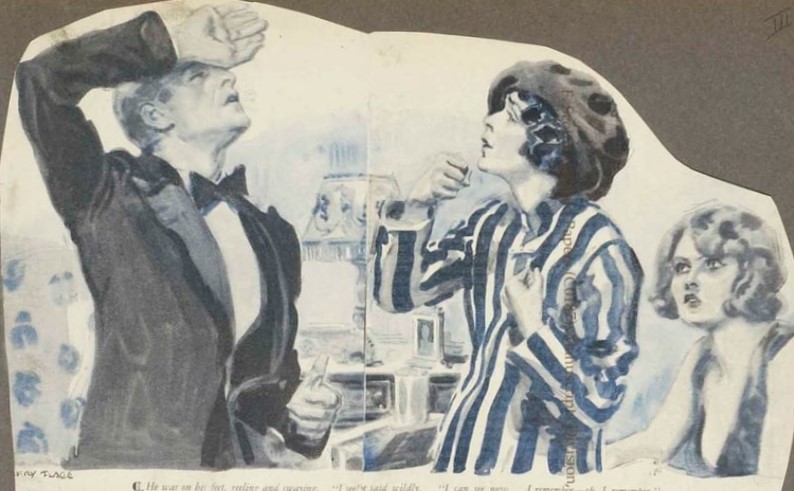

Then he too was on his feet, reeling and swaying.

“Oh-h-h-h!” he cried.

“Charley,” sobbed Diana, “remember, remember, remember!”

“I see!” he said wildly. “I can see now—I remember, oh I remember!”

With a choking sob his whole body seemed to wilt under him and he pitched back senseless into his chair.

In a minute the two girls were beside him.

“He’s fainted!” Diana cried—”get some water quick.”

“You devil!” screamed Elaine, her face distorted. “Look what’s happened! What right have you to do this? What right? What right?”

“What right?” Diana turned to her with black, shining eyes. “Every right in the world. I’ve been married to Charley Abbot for five years.”

***

Charley and Diana were married again in Greenwich early in June. After the wedding her oldest friends stopped calling her Diamond Dick—it had been a most inappropriate name for some years, they said, and it was thought that the effect on her children might be unsettling, if not distinctly pernicious.

Yet perhaps if the occasion should arise Diamond Dick would come to life again from the colored cover and, with spurs shining and buckskin fringes fluttering in the breeze, ride into the lawless hills to protect her own. For under all her softness Diamond Dick was always hard as steel—so hard that the years knew it and stood still for her and the clouds rolled apart and a sick man, hearing those untiring hoofbeats in the night, rose up and shook off the dark burden of the war.

“Diamond Dick and the First Law of Woman” was written in Great Neck in December 1923. International bought it for $1500.

Fitzgerald had been counting on his play, The Vegetable, to solve his money problems. After The Vegetable failed at its Atlantic City tryout in November 1923, he was compelled to write himself out of debt with stories. Between November 1923 and April 1924 he wrote ten stories: “The Sensible Thing,” “Rags Martin-Jones and the Pr-nce of W-les,” “Diamond Dick and the First Law of Woman,” “Gretchen’s Forty Winks,” “The Baby Party,” “The Third Casket,” “One of My Oldest Friends,” “The Pusher-in-the-Face,” “The Unspeakable Egg,” and “John Jackson’s Arcady.” These were competent commercial stories which paid off Fitzgerald’s debts and financed the writing of The Great Gatsby on the Riviera in the summer of 1924.

Published in Hearst’s International magazine (April 1924); the notes on the page are by F. Scott Fitzgerald ("tearsheets").

Illustrations by James Montgomery Flagg.