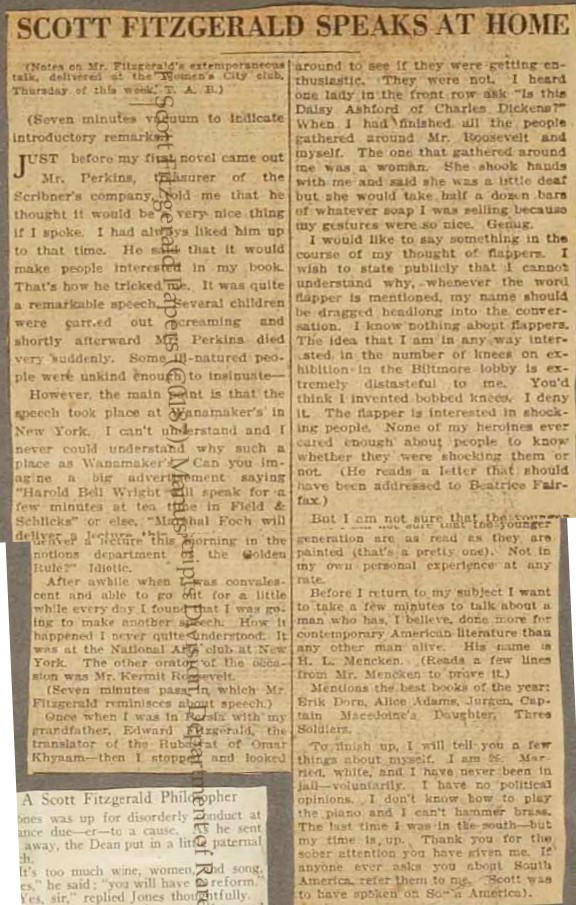

Scott Fitzgerald Speaks At Home

(Notes on Mr Fitzgerald's extemporaneous talk, delivered at the Women's City club. Thursday of this week, T. A. B.)

(Seven minutes vacuum to indicate introductory remarks.)

Just before my novel came out Mr. Perkins, treasurer of the Scribner's company, told me that he thought it would be very nice thing if I spoke. I had always liked him up to that time. He said that it would make people interested in my book. That's how he tricked me. It was quite a remarkable speech. Several children were carried out screaming and shortly afterward Mr Perkins died very suddenly. Some ill-natured people were unkind enough to insinuate—

However, the main point is that the speech took place at Wanamaker's in New York. I can't understand and I never could understand why such a place as Wanamaker's Can you imagine a big advertisement saying “Harold Bell Wright will speak for a few minutes at ten time in Field&Schlicks” or else. “Marshall Foch will deliver a lecture this morning in the notions department or the Golden Rule? Idiotic.

After awhile when I was convalescent and able to go out for a little while every day I found that I was going to make another speech. How it happened I never quite understood. It was at the National Arts club at New York. The other orator of the occasion was Mr. Kermit Roosevelt.

(Seven minutes pass in which Mr Fitzgerald reminisces about speech.)

Once when l was In Persia with my grandfather, Edward Fitzgerald, the translator of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khyaam—then I stopped and looked around to see if they were getting enthusiastic. They were not. I heard one lady in the front row ask “Is this Daisy Ashford of Charles Dickens?” When I had finished all the people gathered around Mr. Roosevelt and myself. The one that gathered around me was a woman. She shook hands with me and said she was a little deaf but she would take half a dozen bars of whatever soap I was selling because my gestures were so nice. Genug.

I would like to say something to the course of my thought of flappers. I wish to state publicly that I cannot understand why, whenever the word flapper is mentioned, my name should be dragged headlong into the conversation. I know nothing about flappers. The idea that I am in any way interested in the number of knees on exhibition in the Biltmore lobby is extremely distasteful to me. You'd think I Invented bobbed knees. I deny it. The flapper is interested in shocking people. None of my heroines ever cared enough about people to know whether they were shocking them or not. (He reads a letter that should have been addressed to Beatrice Fairfax.)

But I am not sure that the younger generation are as read as they are painted (that's a pretty one). Not in my own personal experience at any rate.

Before I return to my subject I want to take a few minutes to talk about a man who has, I believe, done more for contemporary American literature than any other man alive. His name is H. L. Mencken. (Reads a few lines from Mr. Mencken to prove it.)

Mentions the best books of the year: Erik Dorn, Alice Adams, Jurgen, Captain Macedoine's Daughter, Three Soldiers.

To finish up. I will tell you a few things about myself. I am 25. Married, white, and I have never been in jail—voluntarily. I have no political opinions. I don’t know how to play the piano and I can’t hammer brass. The last time I was in the south—but my time is up. Thank you for the sober attention you have given me. If anyone ever asks you about South America, refer them to me. Scott was to have spoken on South America).

Published in St. Paul Daily News newspaper (4 December 1921), City Life Section.