Inside the House

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

When Bryan Bowers came home in the late afternoon, three boys were helping Gwen to decorate the tree. He was glad, for she had bought too big a tree to climb around herself, and he had not relished the prospect of crawling over the ceiling.

The boys stood up as he came in, and Gwen introduced them:

“Jim Bennett, daddy, and Satterly Brown you know, and Jason Crawford you know.”

He was glad she had said the names. So many boys had been there throughout the holidays that it had become somewhat confusing.

He sat down for a moment.

“Don't let me interrupt. I'll be leaving you shortly.”

It struck him that the three boys looked old, or certainly large, beside Gwen, though none was over sixteen. She was fourteen, almost beautiful, he thought—would be beautiful, if she had looked a little more like her mother. But she had such a pleasant profile and so much animation that she had become rather too popular at too early an age.

“Are you at school here in the city?” he asked the new young man.

“No, sir. I'm at S'n Regis; just home for the holidays.”

Jason Crawford, the boy with the wavy yellow pompadour and horn-rimmed glasses, said, with an easy laugh:

“He couldn't take it here, Mr. Bowers.”

Bryan continued to address the new boy:

“Those little lights you're working at are the biggest nuisance about a Christmas tree. One bulb always misses and then it takes forever to find which one it is.”

“That's just what happened now.”

“You said it, Mr. Bowers,” said Jason.

Bryan looked up at his daughter, balanced on a stepladder.

“Aren't you glad I told you to put these men to work?” he asked. “Think of old daddy having to do this.”

Gwen agreed from her precarious perch: “It would have been hard on you, daddy. But wait till I get this tinsel thing on.”

“You aren't old, Mr. Bowers,” Jason offered.

“I feel old.”

Jason laughed, as if Bryan had said something witty.

Bryan addressed Satterly:

“How do things go with you, Satterly? Make the first hockey team?”

“No, sir. Never really expected to.”

“He gets in all the games,” Jason supplied.

Bryan got up.

“Gwen, why don't you hang these boys on the tree?” he suggested. “Don't you think a Christmas tree covered with boys would be original?”

“I think——” began Jason, but Bryan continued:

“I'm sure none of them would be missed at home. You could call up their families and explain that they were only being used as ornaments till after the holidays.”

He was tired, and that was his best effort. With a general wave, he went toward his study.

Jason's voice followed him:

“You'd get tired seeing us hanging around, Mr. Bowers. Better change your mind about letting Gwen have dates.”

Bryan turned around sharply. “What do you mean about 'dates'?”

Gwen peeked over the top of the Christmas tree. “He just means about dates, daddy. Don't you know what a date is?”

“Well now, will one of you tell me just exactly what a date is?”

All the boys seemed to begin to talk at once.

“Why, a date is——”

“Why, Mr. Bowers——”

“A date——”

He cut through their remarks:

“Is a ‘date’ anything like what we used to call an engagement?”

Again the cacophony commenced.

“——No, a date is——”

“——An engagement is——”

“——It's sort of more——”

Bryan looked up at the Christmas tree from which Gwen's face stared out from the tinsel somewhat like the Cheshire cat in Alice in Wonderland.

“Heaven's sakes, don't fall out of the tree about it,” he said.

“Daddy, you don't mean to say that you don't know what a date is?”

“A date is something you can have at home,” said Bryan. He started to go to his study but Jason supplied: “Mr. Bowers, I can explain to you why Gwen won't fall out of the tree——”

Bryan closed his door on the remark and stood near it.

“That young man is extremely fresh,” he thought.

Stretched out on his divan for half an hour, he let the worries of the day slip from his shoulders. At the end of that time there was a knock, and he sat up, saying:

“Come in… Oh, hello, Gwen.” He stretched and yawned.

“How's your metabolism?”

“What's metabolism? You asked me that one other afternoon.”

“I think it's something everybody has. Like a liver.”

She had a question to ask him and did not pursue the subject further:

“Daddy, did you like them? Those boys?”

“Sure.”

“How do you like Jason?”

He pretended to be obtuse.

“Which one was he?”

“You know very well. Once you said he was fresh. But he wasn't this afternoon, did you think?”

“The boy with all the yellow fuzz?”

“Daddy, you know very well which one he was.”

“I wasn't sure. Because you told me if I didn't let you go out alone at night, Jason wouldn't come to see you again. So I thought this must be some boy who looked like him.”

She shook off his teasing.

“I do know this, daddy: That if I'm not allowed to have dates, nobody's going to invite me to the dance.”

“What do you call this but a date? Three boys. If you think I'm going to let you race around town at night with some kid, you're fooling yourself. He can come here any night except a school night.”

“It isn't the same,” she said mournfully.

“Let's not go over that. You told me that all the girls you knew had these dates, but when I asked you to name even one——”

“All right, daddy. The way you talk you'd think it was something awful we were going to do. We just want to go to the movies.”

“To see Peppy Velance again.”

She admitted that was their destination.

“I've heard nothing but Peppy Velance for two months. Dinner's one long movie magazine. If that girl is your ideal, why don't you be practical about it and learn to tap like her? If you just want to be a belle——”

“What's a belle?”

“A belle?” Bryan was momentarily unable to understand that the term needed definition. “A belle? Why, it's what your mother was. Very popular—that sort of thing.”

“Oh. You mean the nerts.”

“What?”

“Being the nerts—having everybody nerts about you.”

“What?” he repeated incredulously.

“Oh, now, don't get angry, daddy. Call it a belle then.”

He laughed, but as she stood beside his couch, silent and a little resentful, a wave of contrition went over him as he remembered that she was motherless. Before he could speak, Gwen said in a tight little voice:

“I don't think your friends are so interesting! What am I supposed to do—get excited about some lawyers and doctors?”

“We won't discuss that. You have the day with your friends. When you're home in the evening, you've got to be a little grown up. There's a lawyer coming here tonight to dinner, and I'd like you to make a good impression on him.”

“Then I can't go to the movies?”

“No.”

Silent and expressionless, save for the faint lift of her chin, Gwen stood a moment. Then she turned abruptly and left the room.

II

Mr. Edward Harrison was pleased to find his friend's little girl so polite and so pleasant to look at. Bryan, wanting to atone for his harshness of the afternoon, introduced him as the author of “The Music Goes Round and Round.”

For a moment, Gwen looked at Mr. Harrison, startled. Then they laughed together.

During dinner, the lawyer tried to draw her out:

“Do you plan to marry? Or to take up a career?”

“I think that I'd like to be a debutante.” She looked at her father reproachfully, “And maybe have dates on the side. I haven't got any talents for a career that I know about.”

Her father interrupted her:

“She has though. She ought to make a good biologist—or else she could be a chemist making funny artificial fingernails.” He changed his tone: “Gwen and I had a little run-in on the subject of careers this afternoon. She's stage-struck, and I'd rather have her do something about it than just talk.”

Mr. Harrison turned to Gwen. “Why don't you?” he asked. “I can give you some tips. I do a lot of theatrical business. Probably know some of your favorites.”

“Do you know Peppy Velance?”

“She's a client of mine.”

Gwen was thrilled.

“Is she nice?”

“Yes. But I'm more interested in you. Why not go in for a career if your father thinks you have the necessary stuff?”

***

How could Gwen tell him it was because she was happy the way things were? How could she explain to him what she hardly knew herself—that her feeling for Peppy Velance only stood for loveliness—enchanted gardens, ballrooms through which to walk with enchanted lovers? Starlight and tunes.

The stage! The very word frightened her. That was work, like school. But somewhere there must exist a world of which Peppy Velance's pictures were only an echo, and this world seemed to lie just ahead—proms and parties of people at gay resorts. She could not cry out to Mr. Harrison, “I don't want a career, because I'm a romantic little snob. Because I want to be a belle, a belle, a belle”—the word ringing like a carillon inside her.

So she only said:

“Please tell me about Peppy Velance.”

“Peppy Velance? Let's see.”

He thought for a moment. “She's a kid from New Mexico. Her name's really Schwartze. Sweet. About as much brains as the silver peacock on your buffet. Has to be coached before every scene, so she can talk English. And she's having a wonderful time with her success. Is that satisfactory?”.

***

It was far from being satisfactory to Gwen. But she didn't believe him.

He was an old man, about forty, like her father, and Peppy Velance had probably never looked at him romantically.

The important thing was that Jason would arrive presently, and maybe two other boys and a girl. They would have some sort of time—in spite of the fact that a sortie into the world of night was forbidden.

“One girl at school knows Clark Gable,” she said, switching the subject. “Do you know him, Mr. Harrison?”

“No,” Mr. Harrison said in such a funny way that both father and daughter looked at him. His face had turned gray.

“I wonder if I could ask for a cup of coffee.”

The host stepped on the bell.

“Do you want to lie down, Ed?”

“No, thanks. I brought a brief case of work to do on the train and the strain on the eyes always seems to affect the old pump.”

Being one of those who had made an unwelcome breakfast of chlorine gas eighteen years before, Bryan understood that Mr. Harrison could never be quite sure. As the other man drank his coffee, the world was still swimming and he felt the need of telling this pretty little girl something—before the tablecloth got darker.

“Were you offended at what I said about Peppy Velance? You were. I saw you wondering how an old man like me would dare even talk about her.”

“Honestly——”

He waved her silent with a feeling that his own time was short.

“I didn't want to give you the idea that all actresses are as superficial as Peppy. It's a fine career. Lots of intelligent women go into it now.”

What was it that he wanted to tell her? There was something in that eager little face that he longed to help.

He shook his head from side to side when Bryan asked him once more if he would like to lie down.

“Of course, it's better to do things than to talk about them,” he said, catching his breath with an effort.

He choked on the coffee. “Nobody wants a lot of bad actresses. But it would be nice if all girls were to do something.”

As his weakness increased he felt that, perhaps, it was this pretty little girl's face he was fighting. Then he fainted.

Afterwards he was on his feet with Bryan's arm supporting him.

“No… Here on Gwen's sofa … till I can get the doctor… Gently… There you are… Gwen, I want you to stay in the room a minute.”

She was thinking:

“Jason will be here any time now.” She wished her father would hurry at the phone. Growing up during her mother's illness had inevitably made her callous about such things.

Their doctor lived almost across the street. When he arrived, she and her father retired to his study.

“What do you think, daddy? Will Mr. Harrison have to go to a hospital?”

“I don't know whether they'll want to move him.”

“What about Jason then?”

Abstracted, he only half heard her. “I hope it's nothing serious about Mr. Harrison, but did you notice the color of his face?”

The doctor came into the study and held a quiet conversation with him, from which Gwen caught the words “trained nurse,” and “I'll call the drugstore.”

As Bryan started into the other room, she said:

“Daddy, if Jason and I went out——”

She broke off as he turned.

“You and Jason aren't going out. I told you that.”

“But if Mr. Harrison's got to stay in the guest room right next door, where you can hear every word——”

She stopped again at the expression in her father's face when what she was saying dawned on him.

“Call Jason right away and tell him not to come,” he said. He shook his head from side to side: “Good Lord! Whose little girl are you?”

III

Six days later Gwen came home, propelling herself as if she were about to dive into a ditch just ahead. She wore a sort of hat that evidently heaven had sent down upon her. It had lit as an ornament on her left temple, and when she raised her hand to her head, it slid—the impression being that it was held by an invisible elastic, which might snap at any moment and send it, with a zip, back into space.

“Where did you get it?” the cook asked enviously as she came in through the pantry entrance.

“Get what?”

“Where did you get it?” her father asked as she came into his study.

“This?” Gwen asked incredulously.

“It's all right with me.”

The maid had followed her in, and he said, in answer to her question:

“We'll have the same diet ordered for Mr. Harrison. Wait a minute—if Gwen's hat floats out the window, take a shotgun out of the closet—and see if you can bring it down, like a duck.”

In her room, Gwen removed the article of discussion, putting it delicately on her dresser for present admiration. Then she went to pay her daily visit to Mr. Harrison.

He was so much better that he was on the point of getting up. When Gwen came in, he sent the nurse for some water and lay back momentarily. To Gwen he looked more formidable as he got better. His hair, from lack of cutting, wasn't like the smooth coiffures of her friends. She wished her father knew handsomer people.

“I'm about to get up and make my arrangements to go back to New York to work. Before I go, though, I want to tell you something.”

“All right, Mr. Harrison. I'm listening.”

“It's seldom you find beauty and intelligence in the same person. When you do they have to spend the first part of their life terribly afraid of a flame that they will have to put out someday——”

“Yes, Mr. Harrison——”

“——and sometimes they spend the rest of their life trying to wake up that same flame. Then it's like a kid trying to make a bonfire out of two sticks, only this time one of the sticks is the beauty they have lost and the other stick is the intelligence they haven't cultivated—and the two sticks won't make a bonfire—and they just think that life has done them a dirty trick, when the truth is these two sticks would never set fire to each other. And now go call the nurse for me, Gwen.” As she left the room he called after her, “Don't be too hard on your father.”

She turned around from the door—“What do you mean, don't be hard on father?”

“He loved somebody who was beautiful, like you.”

“You mean mummy?”

“You do look like her. Nobody could ever actually be like her.” He broke off to write a check for the nurse, and as if he was impelled by something outside himself he added, “So did many other men.” He brought himself up sharply and asked the nurse, “Do I owe anything more to the night nurse?” Then once again to Gwen:

“I want to tell you about your father,” he said. “He never got over your mother's death, never will. If he is hard on you, it is because he loves you.”

“He's never hard on me,” she lied.

“Yes, he is. He is unjust sometimes, but your mother——” He broke off and said to the nurse, “Where's my tie?”

“Here it is, Mr. Harrison.”

After he had left the house in a flurry of telephoning, Gwen took her bath, weighted her fresh, damp hair with curlers, and drew herself a mouth with the last remnant from a set of varicolored lipsticks that had belonged to her mother. Encountering her father in the hall she looked at him closely in the light of what Mr. Harrison had said, but she only saw the father she had always known.

“Daddy, I want to ask you once more. Jason has invited me to go to the movies with him tonight. I thought you wouldn't mind—if there were four of us. I'm not absolutely sure Dizzy can come, but I think so. Since Mr. Harrison's been here I haven't been able to have any company.”

“Don't do anything about it until you've had your dinner,” Bryan said. “What's the use of having an admirer if you can't dangle him a little?”

“Dangle how, what do you mean?”

“Well, I just meant make him wait.”

“But, daddy, how could I make him wait when he's the most important boy in town?”

“What is this all about?” he demanded. “Seems to be a question of whether this prep-school hero has his wicked way with you or whether I have mine. And anyhow, it's just possible that something more amusing will turn up.”

Gwen seemed to have no luck that night—on the phone Dizzy said:

“I'm almost sure I can go, but I don't know absolutely.”

“You call me back whatever happens.”

“You call me. Mother thinks I can go, but she doesn't think she can do anything now, 'cause there's something under the sink and father hasn't come home.”

“The sink!”

“We don't know exactly what it is; it may be a water main or something. That's why everybody's afraid to go downstairs. I can't tell you anything definite until father comes home.”

“Dizzy! I don't know what you're talking about.”

“We're so upset out here too. I'll explain when I see you. Anyhow, mother's telling me to put the phone down”—there was a momentary interruption—“so they can get to the plumber.”

Then the phone hung up with an impact that suggested that all the plumbers in the world were arriving in gross.

Immediately the phone rang again. It was Jason.

“Well, how about it, can we go to the movies?”

“I don't know. I just finished talking to Dizzy. The water main's busted and she has to have a plumber.”

“Can't you go to the picture whether she can or not? I've got the car and our chauffeur.”

“No, I can't go alone and Dizzy's got this thing.”

The impression in Gwen's voice was that plague was raging in the suburbs.

“What?”

“Never mind, never mind. I don't understand it myself. If you want to know more about it call up Dizzy.”

“But Peppy Velance is in Night Train at the Eleanora Duse Theater—you know, the little place just about two blocks from where you live.”

There was a long pause. Then Gwen's voice said: “A-l-1 right. I'll go whether Dizzy can go or not.”

She met her father presently with a guilty feeling, but before she could speak he said:

“Put on your hat—and your rubbers; feels stormy outside; plans are changed and we're dining out.”

“Daddy, I don't want to go out. I've got homework to do.”

He was disappointed.

“I'd rather stay here,” Gwen continued. “I'm expecting company.”

At the false impression she was giving she felt something go out of her. With an attempt at self-justification she added, “Daddy, I get good marks at school, and just because I happen to like some boys——”

Bryan tied his muffler again and bent over to pull on his overshoes. “Good-by,” he said.

“What do you mean?” inquired Gwen uncertainly.

“I merely said good-by, darling.”

“But you kind of scared me, daddy, you talk as if you were going away forever.”

“I won't be late. I just thought you might come along, because someone amusing might be there.”

“I don't want to go, daddy.”

IV

But after her father had gone it was no fun sitting beside the phone waiting for Jason to call. When he did phone, she started downstairs to meet him—she was still in a bad humor—a fact that she displayed to one of the series of trained nurses that had been taking care of Mr. Harrison. This one had just come in and she wore blue glasses, and Gwen said with unfamiliar briskness:

“I don't know where Mr. Harrison is; I think he was going to meet daddy at some party and I guess they will be back sometime.”

On her way down in the elevator she thought: “But I do know where daddy is.”

“Stop!” she said to the elevator man. “Take me upstairs again.”

He brought the car to rest.

But a great stubbornness seemed to have come over Gwen with her decision to be disobedient.

“No, go on down,” she said.

It haunted her though when she met Jason and they trudged their way through the gathering snowstorm to the car.

They had scarcely started off before there was a short struggle.

“No, I won't kiss you,” Gwen said. “I did that once and the boy that kissed me told about it. Why should I? Nobody does that any more—at my age anyhow.”

“You're fourteen.”

“Well, wait till I'm fifteen then. Maybe it'll be the thing to do by that time.”

They sank back in opposite corners of the car. “Then I guess you won't like this picture,” said Jason, “because I understand it's pretty hot stuff. When Peppy Velance gets together with this man in the dive in Shanghai I understand——”

“Oh, skip it,” Gwen exploded.

She scarcely knew why she had liked him so much an hour before.

The snow had gathered heavily on the portico of the theater with the swirl of a Chesapeake Bay blizzard, and she was glad of the warmth within. Momentarily, as the newsreel unwound, she forgot her ill-humor, forgot her unblessed excursion into the night—forgot everything except that she had not told the nurse where her father could be found.

At the end of the newsreel she said to Jason:

“Isn't there a drugstore where I could phone home, where we could go out to for just a minute?”

“But the feature's going on in just a minute,” he objected, “and it's snowing so hard.”

All through the shorts, though, it worried her, so much that in a scene where Mickey Mouse skated valiantly over the ice she seemed to see snow falling into the theater too. Suddenly she grabbed Jason's arm and shook him as if to shake herself awake—though she didn't feel asleep—because the snow was falling. It was falling in front of the screen in drips and then in larger pebblelike pieces and then in a scatter of what looked like snowballs. Other people must have noticed the same phenomenon at the same time, for the projecting machine went off with a click and left the house dark; the dim house lights went on and the four ushers on duty in the little picture house ran down the aisles with confused expressions to see what the trouble was.

Gwen heard a quick twitter of alarm behind her; a stout man who had stumbled over them coming in said in an authoritative voice, “Say, I think the ceiling is caving in.” And immediately several people rose around them.

“Hold on,” the man cried. “Don't anybody lose their heads.”

It was one of those uncertain moments in a panic where tragedy might intervene by an accidental word, and as if realizing this a temporary hush came over the crowd. The ushers stopped in their tracks. The first man to see and direct the situation was the projector operator who came out from his booth and leaned over the balcony, crying down:

“The snow has broken through the roof. Everybody go out the side exits marked with the little red lights. No, I said the side exits—the little red lights.” Trouble was developing at the main entrance too, but he didn't want them to know about it. “Don't rush; you're just risking your own lives. You men down there crack anybody that even looks as if they were going to run.”

After an uncertain desperate moment the crowd decided to act together.

They filed slowly out through the emergency exits, some of them half afraid even to look toward the screen now only a white blank almost imperceptible through the interior snowstorm that screened it in turn. They all behaved well, as American crowds do, and they were out in the adjoining street and alley before the roof gave way altogether.

Gwen went out calmly.

What she felt most strongly in the street with the others was that the durn snow might have waited a little longer because Peppy Velance's picture was about to start.

V

The manager had been the last to leave and he was now telling the anxious crowd that everyone had left the theater before the roof fell in. It was only then that Gwen thought of Jason and realized that he was no longer with her——

That, in fact, from the moment of the near calamity he had not been beside her at all—but just might have been snowed under by the general collapse. Then—as she joined the throng of those who had lost each other and were finding each other again in the confusion—her eye fell upon him on the outskirts of the crowd and she started toward him.

She ran against policemen coming up and small boys rushing toward the accident and she was held up by the huge drift of snow that still gathered about the fallen portico.

When she was clear of the crowd, Jason was somehow out of sight. But she had a dollar in her pocket, and she hesitated between trying to get a taxi or walking the few blocks home. She decided on the latter.

The snow that had brought down the movie house continued. She had meant to be home surely before her father and had calculated on only one hour of time that she would never be able to account for to herself—but time she knew that sooner or later she would account for to her father.

As she walked along she thought that she had made the nurse wait, too, but now she was almost home and she could straighten that out. As she passed the second block she thought of Jason with contempt, and thought:

“If he couldn't wait for me why should I wait for him?”

She reached the apartment prepared to face her father with the truth and what necessary result would evolve.

VI

There was a coat of snow on her shoulders as she came into the apartment.

Her father in the sitting room heard her key in the lock and came to the door before she opened it. “I have been worried,” he said. “You've never gone out before against my orders. What happened?”

“We went to see Peppy Velance at the small theater just over a couple of blocks from here and, daddy, the roof fell in.”

“What roof?”

“The roof of the theater.”

“What!”

“Yes, daddy, the roof fell in.”

“Was anybody killed?”

“No, they got us all out first. Jason didn't bring me home, but I saw him afterward and I know that he's all right, and the man said nobody was hurt.”

“I'm glad I didn't think of all that.”

“It was the snow,” said Gwen. “I know you're pretty sore, but it's been so dull this whole week, with Mr. Harrison sick and this is the last Peppy Velance was going to be at the Eleanora Duse——”

“Peppy Velance was here. She left ten minutes ago. She was waiting to see you.”

“What?”

“You saw her tonight, even if you didn't know it. She flew down from New York to see Mr. Harrison about some business, but you seemed to be in an awful hurry. Mr. Harrison didn't expect her so soon. We brought her back here because I knew that you might like to meet her properly.”

”Daddy!”

“I suppose you didn't recognize her because she had on blue glasses, but she took them off, and when she's got them off she looks just as human as anyone else.”

Stricken, Gwen sat down and repeated, “Was she here, daddy?”

“Well, Mr. Harrison seems to think so and he ought to know.”

“Where is Peppy Velance now?”

“She and Mr. Harrison had plans to catch the midnight train to New York. He left you his regards. Say, you haven't caught cold, have you?”

Gwen brushed at her eyes, “No, these are only snowflakes. Daddy, do you mean that she was honestly here all that time while I was out?”

“Yes, daughter, but don't cry about it. She left you a little box of lipstick with her name on it and it's on the table.”

“I never thought of her like that,” Gwen said slowly. “I thought there were always a lot of—you know—a lot of attractive men hanging around her. I guess why I didn't recognize her was because there weren't any men hanging around her. Go on, daddy; tell me—at least, was she attractive—like mummy was?”

“She wasn't like mummy, but she was very nice—I hope you didn't catch cold.”

“I don't think so.” She sniffed experimentally, “No, I'm sure I didn't. Isn't it funny I went out and the blizzard came? I wish I'd stayed here where it was safe and warm——” On her way to her room she ruminated aloud:

“I guess most important things happen inside the house, don't they, daddy?”

“You go to bed.”

“All right, daddy.”

Her door closed gently. What went on behind it he would never know. He wrote her a short note saying:

“Peppy Velance and Mr. Harrison are coming to dinner tomorrow night.” He stood it up against the English-history book on the table. Then he moved it to rest against the little tin satchel that the maid would fill with sandwiches for school in the morning.

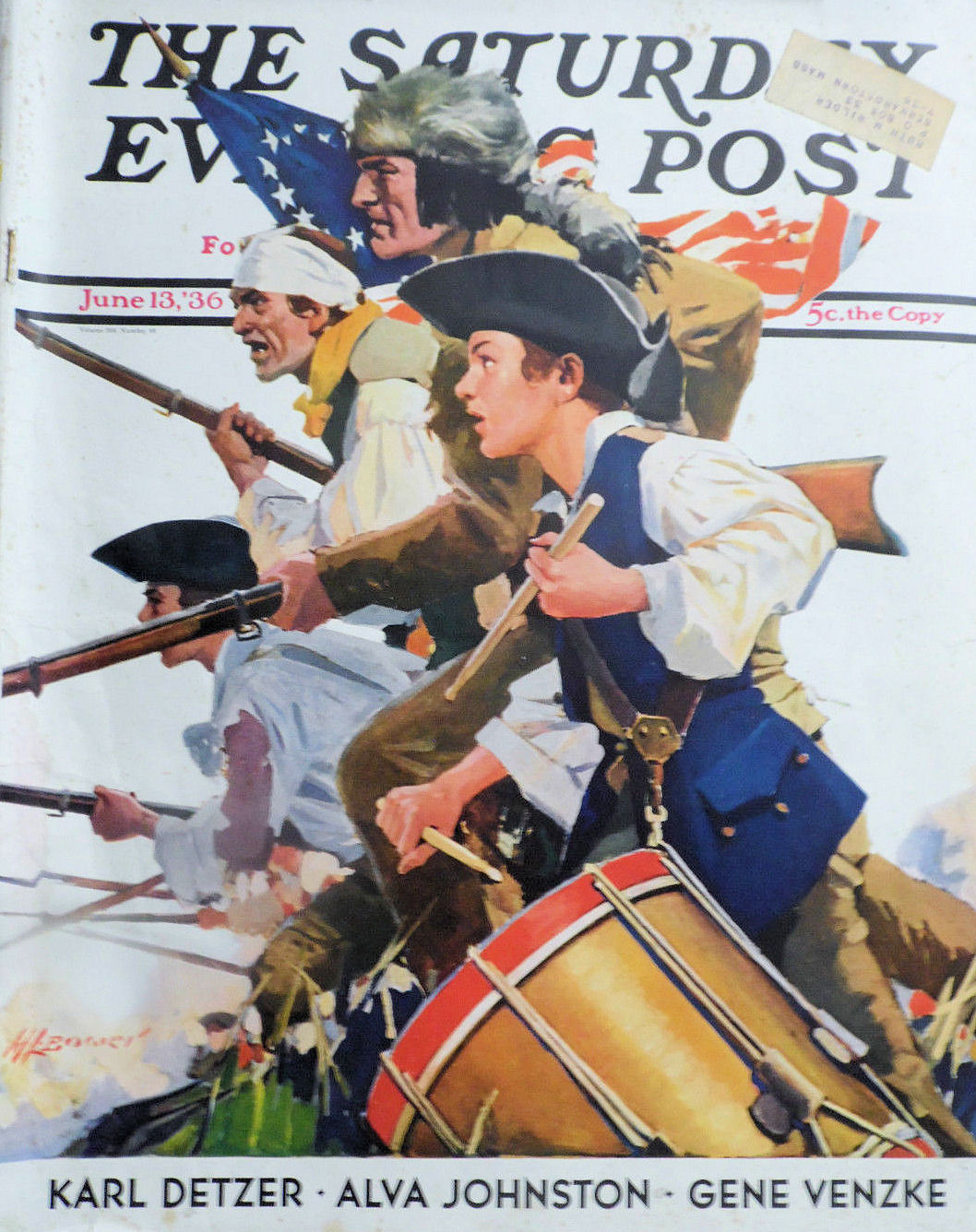

Published in The Saturday Evening Post (13 June 1936)

Published in The Saturday Evening Post magazine (13 June 1936).

Illustrations by Henrietta McCaig Starrett.