Crazy Sundays: F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood

by Aaron Latham

5 Tender Is the Night and the Movies

1

It was four o’clock in the morning when Bill Warren’s phone rang.

“Get over here and straighten this out,” said a man with a thick voice at the other end. He meant straighten out Tender Is the Night.

The seventeen-year-old never protested. He dressed in his dark Baltimore home at 605 North Charles Street, then headed for 1307 Park Avenue. He found the author standing at a high, old-fashioned desk. Scott had taken to doing all his writing on his feet, but if this eccentricity made him look like a pastor at his pulpit, he was one with liquor on his breath. Bill walked over and stood beside him, and they both looked down at the new pages covered with handwriting which could not walk a straight line. “He wanted me to make sense out of what he had written,” Warren remembers, “but sometimes I couldn’t even figure out the words.”

Bill went to work editing, rewriting, changing, while Scott looked on, growing more and more impatient. The boy crossed out “he expostulated” and wrote in “he said.” Scott put his arm around Bill, whom he had already taken as his godson.

“Don’t change that,” he said. “That’s why I’m who I am. Who the hell are you?”

The unpublished beginner and the recognized author had the same argument almost every day. “I always thought that dialogue was very well contained if you used ’he said,’ ’she said,’” Warren explains. “Scott would write, ’he expostulated,’ ’he ejaculated,’ ’ ‘Ah,’ he complained.’”

When they weren’t fighting about how to write dialogue, they fought about how. to open chapters. “Scott always wanted to begin chapters with ’The moon shone thinly over the city,’” Warren remembers. “I would begin, ’The trains from the South arrived three times a day. She was on one of them.’”

“How dare you rewrite me?” was Fitzgerald’s standard protest. “How do you know the trains arrived three times a day?”

Warren had an answer: “You told me.”

One night while Scott stood at his desk with his arm around Bill’s shoulder, asking, “Don’t you know the difference between a vowel and a consonant?” Zelda crept into the room. She came up behind Bill and reached around him with both hands as if to cover his eyes to play “Guess who?” But Zelda was not playing. She dug her fingernails into the skin at the rims of the boy’s eyes, then raked the sharp points down over his cheeks and chin, laying open wounds the length of his face. They rushed Warren to the hospital. Fitzgerald had once written, “I left my capacity for hoping on the little roads that led to Zelda’s sanitarium,” and now Bill’s face looked like a map of those roads.

Fitzgerald had begun Tender Is the Night in France eight years before, when Bill Warren was nine years old and Zelda was whole. No mental illness clouded those first drafts: the novel was originally conceived as a story about the movies. Scott called his hero Francis Melarky, made him a motion-picture cameraman, and placed him in Europe.

At first Francis is bored with the whole expatriate merry-go-round. Then he discovers that Earl Brady has come over and is making a picture in Monte Carlo. Tired of doing nothing, Francis drives to Brady’s studio, a little Hollywood marooned on the Riviera, where he hopes to get back into pictures. Making his way across a darkened stage, Francis notices (as George Hanaford in “Magnetism” and Rosemary Hoyt in Tender would after him) that “here and there figures spotted the twilight, figures that turned up ashen faces to him, like souls in purgatory watching the passage of a mortal through.” When the unemployed cameraman finally finds the man he is looking for, the director Brady, he stands in the shadow watching him work, and is thrown “into a sympathetic and approving trance.” Soon Francis, like Gatsby, begins to dream, but he dreams not of a girl like Daisy, nor of a green light across the bay. His dreams are movie dreams:

More than anything in the world he wanted to make pictures. He knew exactly what it was like to carry a picture in his head as a director did and it seemed to him infinitely romantic. Watching, he felt simply enormous promise, an unrolling of infinite possibilities in himself. He felt closer to Brady, murmuring on in his quiet deep-seated voice, than he had to anyone for months.

Moved by his desire to make movies, Francis goes up to Brady and introduces himself. Brady remembers the young cameraman from Hollywood and so offers him some backhanded flattery. “You’ve got ideas,” the producer says. “You’re sort of a stimulating kid. Take for instance authors—I’ve never been able to use their God damn stories, but I kept bringing them out to the coast because they’re stimulating to have around.” Fitzgerald, who would soon be on his way to the coast to write Lipstick, could not have known how prophetic these words would prove to be.

When Francis tells his mother—whom he was to kill later in the story—that he plans a comeback as a cameraman, she reminds her son:

“You told me all they did was make you wait. You said you sat around one whole morning waiting.”

“I did say that, but I explained to you that waiting is just part of the picture business. Everybody’s so much overpaid that when something finally happens you realize that you were making money all the time. The reason it’s slow is because one man’s keeping it all in his head, and fighting the weather and the accidents—”

“Let’s not go over all that again, dear.”

Even before his trip to Hollywood, Fitzgerald already knew what kind of world he would find there.

Mrs. Melarky does not know much about the movies, but like any American mother she does know enough to put Hollywood and drugs together. She calls Brady her son’s “drug-taking friend in Monte Carlo.” Francis tells her, “It’s not everyone who can get the dope habit from a prominent moving-picture director.” Twenty years later Fitzgerald would not be able to dismiss the Hollywood drugs so easily. One of his producers at MGM was hooked.

Brushing aside his mother’s worries, Francis jumps back into pictures. Like his creator, Francis had been away from his art for a long time, but thanks to Brady he sees his direction once again—just as Fitzgerald, writing the story, must have thought that he saw his:

Walking out on the beach for a swim before dinner, Francis evoked from the day’s hope and from the health in his browning body, a robust old thought that work was more fun than anything. He felt that he was a good man and could do things no one else could. The few strangers left on the beach realized this and swaying together clinked glasses to him. “Hurray for Francis Melarky!” He resolved to cut out the beer he drank with his meals, for how could he be at his best when he was short-winded? On the other hand, so he thought perversely, if he became an athlete in perfect trim, how could he respond to such toasts as they had just given him here? To achieve and to enjoy, to be prodigal and openhearted and yet ambitious and wise, to be strong and self-controlled, yet to miss nothing—to do and yet to symbolize… to be both light and dark.

In articulating the aspiring young movie maker’s dilemma—to do and yet symbolize—Fitzgerald had set down his own. On the one hand he wanted to prove that he was a better writer “than any of the young Americans without exception.” On the other hand he wanted to have more fun than anyone else in France. He even took time away from his novel to try to become the man he was writing about—time to sight through a whirring camera, time to make an amateur film. His production crew consisted of Ben Finney and Charles MacArthur, his stars Ruth Goldbeck and Grace Moore. They did most of their shooting on location in Monte Carlo with the Mediterranean stretching about them; up and down the coast the eggshell walls of the beach houses gleamed in the sun; and the Casino, richer than any Diamond as Big as the Ritz, loomed in the background. “Just a real place to rough it,” was Fitzgerald’s description.

Fitzgerald was behaving as though he actually knew how to carry a picture in his head, fighting weather, actors, and accidents. His romantic illusions were fulfilling themselves as the camera zoomed in on… dirty words. It was like photographing a well-inscribed bathroom wall, except that it was really the pink wall of Grace Moore’s villa.

Miss Moore, star of musical comedies, operas, and later the movie One Night of Love, remembered those unprintable words in her autobiography:

One of the devices of the script was to write the titles on the outside walls of my pink villa and photograph them that way. But during the night the collaborators would always think up a few new unprintable titles, and I never knew, when I looked out in the morning, what new four-letter horror would be chalked up on my house to throw into a dither the tourist schoolmarms who might be passing by. I complained and scrubbed once or twice, but the new captions that then appeared were so much worse than the old that it seemed better to do with the four-letter words one knew than those one knew not of.

In their movie, Miss Moore played Princess Alluria, the wickedest woman in Europe, and Miss Goldbeck was cast in a supporting role as the farmer’s daughter. Several of the action shots were filmed on the grounds of the fashionable Hotel de Cap.

When Fitzgerald was not playing cameraman himself, he went on with his story of Francis Melarky, but as he wrote, his hero began to twist beneath his pencil. “About this time a change began to come over Francis,” Fitzgerald put down. “He began to see himself as a more powerful person… The symbol of his power became Earl [Brady].” Francis wanted a director’s privileges not only at the studio but in society; he began to believe that “it needed only a word from him to change entire relations.” To detach a wife from a husband would be as easy as ordering an actress to walk across the stage, or so Francis believed, and he set out to prove that he was right.

As important as the change which came over Francis, however, was a change coming over Fitzgerald himself. Once he became preoccupied with a director—once the director became for him “the symbol of… power”—the author began to lose interest in Francis. Why write a story about a man who ran a camera when he could write about a man who ran the whole show? The year was probably 1927, a time for upheavals. Francis Melarky, like the silent movies, was about to be replaced.

At this point, Fitzgerald broke off working on the Melarky story. Perhaps he, like Francis, felt that “more than anything in the world he wanted to make pictures,” so he took a job in Hollywood. The result was Lipstick. Failing to strike gold in California, the author left the West and moved to Ellerslie, just outside Wilmington, Delaware, where he took up his novel again, but he did not take it up where he had left off. Rather, he decided to scrap Francis and start over. This time he chose as his hero Lew Kelly, a brilliant young director of motion pictures. Kelly’s mind was described as “made up of all tawdry souvenirs of his time, things given away, unearned, like the pictures of celebrities he had once collected from cigarette packages. Somewhere in the littered five-and-ten glowed the low, painful fire of his talent.” We are first introduced to Kelly and his wife Nicole on board a ship bound for Europe. A young actress named Rosemary is also making the crossing. Her ambitious mother persuades her to sneak across from tourist class into first class so that she can meet the prominent movie maker. In this early version of the story, she is literally looking for a director. In the final version, she would find her director, symbolically, in Dick Diver.

In 1931 the author decided to make his second raid on Hollywood. His script for The Redheaded Woman, of course, failed to make his fortune; banished from Metro, he headed back east and back to his novel. He rented a house in Baltimore and there, far from the Riviera, took up the story of his American expatriates.

2

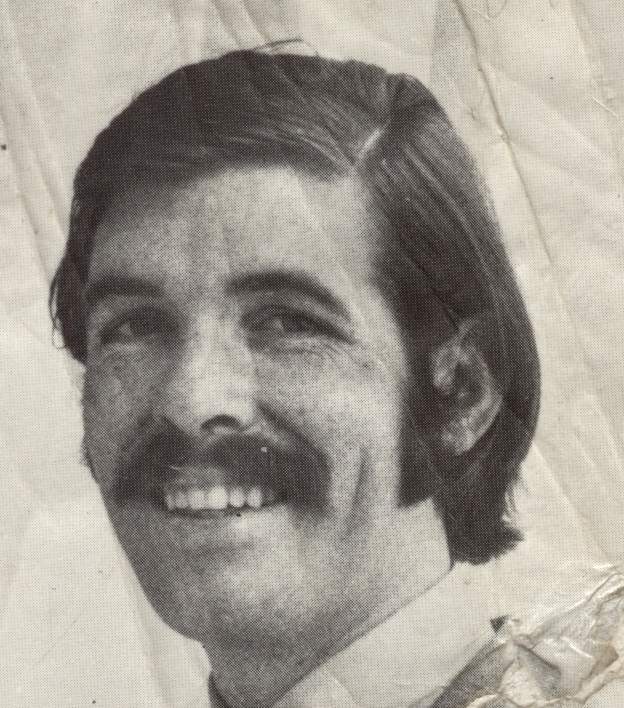

Charles (Bill) Warren met Scott Fitzgerald in Baltimore’s Vagabond Theatre. “I was doing a musical called So What with Gary Moore,” Warren remembers. “I had written the book and the music. We were rehearsing one afternoon very late—all of the chorus girls and skit girls had gone home. I was at the piano playing ’Our Life Will Be a Wow’ and telling this one girl to make the song light, airy, when out of the dark came this great big fedora. I saw a man dressed for winter, overcoat and all, and here it was the dead of summer. The man introduced himself and said, ’I’d like to work with you.’ With youth’s arrogance, I thought, ’Who the hell wouldn’t?’ When he left, everyone asked me, ’Do you know who that was?’ But I didn’t know F. Scott Fitzgerald. Hell, I didn’t know Ernest Hemingway. I was a fast seventeen. After I found out that he wasn’t a ragpicker, no matter what he dressed like, I went to see him.”

Fitzgerald liked Warren because the boy combined two of his dreams: he was in the theatre and he played football. When Scott and Bill first met, Warren was a prep-school star who had just been named All-Maryland. (Later Bill won a football scholarship to Princeton, which pleased Scott, but when he arrived to try out for the varsity, he lasted about as long as had the author of This Side of Paradise—ten days.) One morning Scott woke Bill at two a.m. He also woke a priest. At a nearby church Bill Warren, whose real name was Charles Marquis Warren, was baptized, while Fitzgerald stood as godfather. The godson remembers feeling foolish “getting water sprinkled on my head like a baby.”

During those years Zelda was in and out of the Shepherd Pratt Clinic. Scott would visit her there and the couple, who always competed against one another, would go out to the courts and play tennis. One afternoon Scott took Bill along and insisted that Zelda play the boy. The wife acted as if her husband were backing out of the honeymoon, but Scott ignored her, climbing up into the high judge’s chair to referee the match. The two reluctant players took their places and began to rally. After the first point, Zelda took off her sweater. The judge high up over her head said nothing. After the second point, she reached behind her back, unhooked her bra and tossed it away. Still Scott remained silent. After the third point, Zelda’s short white tennis skirt dropped like a hoop at her feet. After the fourth, she freed herself from her panties.

“I was playing with a stark naked woman,” Warren remembers. “She had a gorgeous body—it was the first time I noticed that a woman could be brown all over. But when you are playing tennis with a naked woman whose husband is watching, you try not to look. I was having a terrible time returning her shots.”

Warren believes that if Scott had told Zelda to stop, she would have, but the author sat up in his chair looking on as if the only bounds being overstepped were the white lines drawn on the courts. The game ended when the clinic attendants brought damp sheets, wrapped them around Zelda, and carried her away. “She didn’t go docilely,” remembers Warren. “She was screaming at Scott.”

Zelda was teaching Scott lessons about tragedy which Aristotle had left out. He retained the young actress Rosemary in his story, but changed his hero from a director to a doctor. The doctor, however, was to be something of a showman. He was not descended from actor George Hanaford (“Magnetism”), cameraman Melarky, and director Kelly for nothing.

Warren worked with Fitzgerald on the final drafts of Tender Is the Night, then they collaborated on a motion-picture treatment of the novel. Some days Bill simply acted as a kind of stenographer. Other days he would take pages covered with Scott’s sprawling handwriting, sit down with a legal pad, and rewrite whole scenes. He remembers especially the shooting episode at the railroad station in Paris, which he reworked, trying to give it a more dramatic structure. In recognition of Bill’s efforts, Scott put him in the book: the author named Nicole’s father Charles Marquis Warren in the first edition of the novel, then changed it to Devereux Warren in later printings. “It was our hidden symbol,” remembers the man who gave his name.

“If I tell you that I wrote part of Tender Is the Night, then you’ll tell me that you wrote The Sun Also Rises,” says Warren. But when the novel was published, eight years after it was begun, Fitzgerald inscribed a copy to his “godson” as follows: “For Charles (Bill) Warren with the hope that our co-operation will show us to prosperity. April 1st (fool’s day 1934).”

In that book Rosemary Hoyt, the young actress, meets Dick Diver on the Riviera and, as she falls in love, realizes that this will be “one of her greatest roles.” Rosemary is the kind of girl who during moments of emotional strain finds herself “wishing the director would come.” And so Dick is perfect for her: he is the most skilled director she has ever known and she wants to submit to him completely. We are told that the “most sincere thing” that she ever said to him was, “Oh, we’re such actors—you and I.” Which happens to be precisely what Helen Avery says to George Hanaford, a professional actor, in “Magnetism.” Rosemary wants Dick to be in a screen test, explaining, “I thought if the test turned out to be good I could take it to California with me. And then maybe if they liked it you’d come out and be my leading man in a picture.” Dick takes a superior attitude. He refuses the test and refuses to be Rosemary’s leading man either in pictures or in private.

Still, Dick is drawn to this actress, this pretty, uncomplicated dream girl so different from his own wife. And his view of her is in many ways tied up in the dreams which the movies have transmitted to us all. Fitzgerald writes of “the current youth worship, the moving pictures with their myriad faces of girl-children, blandly represented as carrying on the work and wisdom of the world.” Rosemary is such a girl-child, the model for the mold. When she leaves France and Dick’s life, he, like so many dreamers, is reduced to going to the movies to see his girl. “I’ve seen you here and there in pictures,” he tells Rosemary when they meet much later. “Once I had Daddy’s Girl run off just for myself!”

Dick Diver is an actor, but only as Gatsby is—perforce and as a layman. His charm, like Gatsby’s personality, is partially based on “an unbroken series of successful gestures.” It is an act, and that is why it is not enough for him. In a passage later cut from the novel, Dick asks Rosemary, “Do you remember you said once, ’Oh, Dick, we’re both such actors’? Well, I’ve more or less retired from that. I expect a good deal of nourishment from people, or else old Diver doesn’t give any out.” Dick Diver had been like the director whom Francis Melarky admired, for “it needed only a word of his to change… relations.” When he stops acting, stops directing, he is already on the road to exile in Hornell, New York. There is something gained: he may be a better doctor now. But there is loss too, enough loss to make the story a tragedy. Before he gave up the act, “the light and glitter of the world” had been in his hands. Now it is dashed and the players scattered.

3

In 1934, when Tender Is the Night appeared in the bookstores, the Depression was hurting book sales much more than the picture business. A few farmers might escape the Oklahoma Dust Bowl by piling into an old Ford and heading for California, but most Americans sought escape from hard times by piling into movie houses. They lost themselves in films like John Ford’s Lost Patrol; went to Frank Capra’s It Happened One Night to see long-legged Claudette Colbert trounce Clark Gable in a hitchhiking contest; fell in love with the man who hated dogs and small children, old bulb-nosed W. C. Fields, star of It’s a Gift. That was stern competition, especially for a book like Fitzgerald’s which offered no refuge—a book which was, in fact, about deterioration. Tender Is the Night sold only thirteen thousand copies—This Side of Paradise had sold twice as many the first week—and left Fitzgerald in financial quicksand.

It did not take long for Scott to see that the lines were forming in front of the theatres, not the bookstalls, and so once again he began to think about show business. After all, the movies had haunted the author and his novel ever since those early chapters about Francis Melarky, the man who wanted to make movies more than anything. Scott decided that he and Warren should write a movie treatment of Tender Is the Night which they would sell to Hollywood. They began by thinking up a dream cast which included Ina Claire, the actress Scott had seen in The Quaker Girl when he was a schoolboy at Newman, and Robert Montgomery, the man he had insulted at the Thalbergs’. The full list of stars considered worthy of the novel’s characters read as follows:

| Nicole Diver— | Katharine Hepburn |

| Miriam Hopkins | |

| Helen Hayes | |

| Ann Harding | |

| Myrna Loy | |

| Dolores del Rio | |

| Dick Diver— | Fredric March |

| Herbert Marshall | |

| Robert Montgomery | |

| Richard Barthelmess | |

| Paul Lukas | |

| Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. | |

| Ronald Colman | |

| Baby Warren— | Kay Francis |

| Ina Claire | |

| Paklin Troubetskoi— | George Raft |

| Ronald Colman | |

| Charles Bickford | |

| Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. |

“Scott didn’t know anything about adaptations,” Warren says. The Tender Is the Night which the author and his young collaborator knocked out in a few weeks for the screen was very different from the novel which had cost eight years. “I would tell him,” Warren remembers, “’If you’re going to do the book, do the book.’ He wouldn’t pay any attention to me. He was going to show them, going to prove that he knew movies.”

The two amateurs opened their story in classic melodramatic form with an accident which brings the hero and heroine together. The mishap takes place during a “short, hilarious gallop” led by Prince Paklin Troubetskoi, an “exiled Russian nobleman and ex-Cossack” who runs a “fashionable girls’ riding school on the shores of Lake Geneva in Switzerland.” A seventeen-year-old American heiress named Nicole Warren, “Troubetskoi’s pet,” “is thrown in a nasty fall and dashed against the base of a tree.” The riding master dispatches one of his pupils to a nearby charity hospital where “Richard Diver,… promising young brain surgeon and psychiatrist, is just completing a delicate operation.” Dr. Diver takes a horse and hurries to the scene of the injury.

Life, when taken in at the local Bijou, was evidently a much simpler puzzle than when confronted in a novel. In the book Nicole has been raped by her father, a rich capitalist, and his act becomes a metaphor for capitalism’s original sin; the “winding mossy ways” of her own mind become her purgatory as she atones for her father’s guilt by going insane. In the movie treatment she simply gets a bump on the head.

At first Dr. Diver thinks of Nicole as just another patient, but eventually they are literally thrown together on a mountainside. “By coincidence,” Dick meets Baby and Nicole in a funicular making a trip up a mountain:

A casual conversation between two of the passengers about the possibilities of the cable that pulls the car breaking seems to upset Nicole… The car begins to tremble and amid the terror of the passengers, Dick’s one thought is for Nicole’s safety. The cable splits and the funicular is precipitated down the incline for a horrible moment, then derailed. It crashes over on its side and amid the confusion that follows, Dick clutches Nicole tightly to his heart. Thankful that she is safe, and realizing that this girl and her future mean everything to him, he… realizes… that he is to be her husband and private doctor for life.

After Dick and Nicole’s marriage, a melody is introduced into the story. The collaborators explained:

In the book, Tender Is the Night, there is much emphasis on the personal charm of the two Divers and on the charming manner in which they’re able to live. In the book this was conveyed largely in description, “fine writing,” poetic passages, etc. It has occurred to us that a similar effect can be transferred to the spectator by means of music, and to accomplish this we have interpolated… a melody written… by Charles W. Warren.

Warren says that he told Fitzgerald, “You don’t insert music. The studios have their own music departments.” But if Scott had a fuzzy understanding of how to write movie treatments, he saw his own art with considerable clarity. He knew that in Tender Is the Night he had told his readers about Dick Diver’s “extraordinary virtuosity with people” without really demonstrating that charm dramatically. In fact, in an early draft of the book he had written: “The shadow of his charm plays about me still, as if to warn me, frighten me away from my story. And it’s the one thing I can never capture—never though I press this lead till it crumbles. You may look through this book for it but you will not find it.” In the novel, we are told almost nothing of the specific acts of charm performed by Dick but rather how he made others feel, and these feelings would have been hard to film.

The camera was to have shown the Divers’ luxurious “Villa Diana” at the top of a steep cliff, and a piano at the bottom. Several workmen are preparing to haul the instrument up the face of the cliff with a rope which is hitched to a team of horses on top. One workman is sitting on the piano, leaning over so that he can reach the keyboard, pecking out the melody to “Our Life Will Be a Wow,” the number Warren was playing when Fitzgerald walked into his life. Suddenly the man and the piano are hoisted into the air as a “fellow workman runs up a zigzag staircase, cut on the side of the stone hill, crying .. . ’Stop the horses!’” The piano settles safely to the ground once again and the man who had risen with it resumes his melody. Nicole, looking “happy and the picture of health,” appears and goes to the piano where she plays “the tune more fully than the workman.” When Baby Warren enters with her boy friend, “a Prince Somebody from the Balkans,” the music changes: the prince “plays a repetition of the previous melody but now comically in the highest octave on the piano.” Baby herself takes over and “again there is an ominous note in the score as [she] finishes the tune in the bass cleff. ”

The use of music in a motion picture to create a kind of poetic emotional state was a commendable idea. It was not, however, a particularly new one; even before the old movie houses were wired for talkies, they all had pianos. Still, Fitzgerald was onto something. His use of music in Tender Is the Night seems a little contrived, but much later, as he worked on Madame Curie at MGM, he would revive his ideas about melody and handle them more skillfully. In Fitzgerald’s script for that film, an exiled Polish pianist sits alone in a shabby Paris hotel room and serenades his lost country.

While their marriage is still new, the Divers are happy, but “the luxury and ample supply of the Warrens’ money” begin to rust Dick’s more important talents. His “charm and ability to stage-manage his parties” become a substitute for his profession. The problem is that the Warrens have made him a showman when what he wanted to be was a doctor, and “inwardly there have been longings and old regrets…”

Soon jealousy makes an already tense situation even worse. One day, in the same way that Dick and Nicole were thrown together in the cable-car crash, Dick and the young actress Rosemary are thrown at one another in an automobile:

Bewildered and uncertain, Nicole sits next to Dick who is driving. It is when Dick has stepped on the accelerator for a short straightaway run that Nicole, laughing hysterically, clutches the steering wheel and swerves the car off the road, down a little incline at the bottom of which it rolls over on its side. Dick’s leg, unknown to the others, is pinned agonizingly under the side of the car. Rosemary is thrown against him in such a way that it looks as though he might have crawled over to her.

In the next weeks, suspicion and irritation mount until Dick and Nicole separate. “Perhaps I won’t make such a mess of things alone,” Dick vows.

Nicole and her former riding teacher Paklin Troubetskoi begin a flirtation—just as Nicole and Tommy Barban do in the novel. The motion-picture treatment is true to the book up to the point where Nicole’s virtue is tested:

Driving through the pleasant countryside Nicole does not object when Paklin turns the car into a drive that leads to a small mountain hotel. She hovers, outwardly tranquil, as Paklin fills out the police blanks and registers the names—his real, hers false. Their room is simple, almost ascetic…

Moment by moment all that Dick has taught her, all that he has grown to mean to her, comes back. Realizing that she cannot go through with her “affair,” she tells Paklin so, as gently as she can…

“You don’t know what a really good time is,” Paklin says angrily. “You’ve never had one. You couldn’t be gay—really gay, with a psychiatrist nagging you all the time. Now you’re throwing over what could be the happiest part of your life—”

“Because I love Dick.”

In real life Zelda had had an affair with an “officer of aviation” who wore a white uniform and talked “romantically [of] how he want[ed] to smoke opium in Peking.” The novel recorded the wife’s unfaithfulness, but on the screen husbands and wives were different—they were faithful. Or so Fitzgerald thought in 1934. In 1938, he would think differently, calling one of his best screenplays Infidelity.

One of the most moving scenes in the novel describes the way Dick Diver is beaten up first by Italian cab drivers and then by Italian cops. Fitzgerald had actually received such a beating himself while in Rome, and ever after he had hated all of Italy for it. In the movie treatment, however, wish fulfillment seems to take over, so that it is not Dick but his rival Troubetskoi who is beaten. Nicole tries to rescue the riding master but, at the sight of his hamburger face, she dissolves into hysteria. Luckily, that “promising young brain surgeon and psychiatrist” Dick Diver once again is waiting in the wings to save her. Nicole is taken to a hospital and Dick is called in to operate:

Whether he is operating on Nicole to save her for Paklin, Dick doesn’t know, but he is making the attempt regardless.

In the quiet, mechanical smoothness of the operating room, in the midst of his delicate work—with the newness and mystery of this particular operation—and the burning sensation that he is trying to save Nicole for another man, Dick’s nerve fails.

But Nicole, deep in the oblivion of the anesthetic, murmurs once “Dick” and his hand does not falter after that.

By the end of the movie, Dick Diver has become not a symbol of self-destructive charm but simply one more Prince Charming.

When the movie treatment was finished, Fitzgerald staked his collaborator to a trip to Hollywood. Scott hoped that Warren, besides selling himself to the studios, might be able to sell Tender Is the Night. Fitzgerald gave Warren several letters of introduction which were supposed to unlock the movie world for him. He wrote Bess Meredyth, a writer who had shared his own unfortunate entanglement with The Redheaded Woman:

Between your amours, intrigues, affairs, your coquetries, oglings and pawings, triumphs and frustrations, between your bootlegging perfumes over the border and your politeness to Marcel de Sano, most of all for the sake of my love I ask you to find a few minutes to give to the young man, Charles Warren, who presents this letter, a few wise words from a girl who was on the set when Griffith invented the close-up and Cedric Gibbons invented the clothes hanger… Let him sit in your office for a moment, will you, dearie, and inhale the stale but sacred Chesterfield smoke.

Fitzgerald explained that Warren had helped him with a treatment of Tender, but added, “My God, it is third best seller in the country and seems to be about as inadaptable to treatment as was the carrot-topped tart of three years ago.”

Scott wrote to Warburton Guilbert, who was then in Hollywood writing scores:

I saw your show in New York and thought it great stuff and all your promise fulfilled and was delighted to see an old Triangle friend come through. Incidentally, working with this man, Warren, has taken me back to those days of pounding out lyrics to “Puccini Cowboy” and “The Beautiful Chord Come True” and my real favorite of all your early songs—“The Land of the Never Never.”

Fitzgerald wrote George Cukor that Warren “seems to have more stuff than any young man I’ve met since Hemingway, though his specialty is a gift for the theatre rather than for literature.”

Soon Warren was sending Fitzgerald letters from the coast. One informed Scott: “Your name is big and hellishly well known in the studios. You rate out here as a highbrow writer but you rate as a thoroughbred novelist and not a talkie hack and therefore these people look up to you.” The letter went on to suggest, however, that being looked up to was no way to get rich. “Lower your highbrow & help on some trash,” he advised the author of The Great Gatsby and Tender Is the Night. “They buy trash here —they’re quite willing to pay high for it… If you would forget originality and finesse and think in terms of cheap melo theatrics you would probably have made a howling success of your visits here and would likewise have no financial worries now.” (Much later, Warren would follow his own advice and create the world’s most successful television show, Gunsmoke.)

It evidently occurred to Scott that perhaps the young man was right. On a single page he wrote out an outline for a story and sent it off to Warren offering to “go 50-50” if he sold it to a studio. His cast of characters included an “old-fashioned ham actor,” “typical flapper,” “woman who took fan letter answer seriously, and who believed all sorts of junk,” and a “Big Shot writer trying to get in studio.” The story which the writer hoped would end his financial worries went as follows:

Row between extras.

Some of the big stars walk through.

The Big Shot who has been reverently mentioned the entire time finally makes appearance and is insignificant little boob.

Pathetic appeal of extra person or persons who need work desperately and the job is landed by boob who doesn’t need it…

One of the directors commits suicide and someone phones it in immediately and “yes man” who comes out is more interested in who’s gonna take over the picture than the suicide.

Shot of extras with jobs coming off the lot or sets with their make-up and costumes on and their cheeriness and flippancy compared with the ones in the room and how they accept the luck of their fellows.

Fitzgerald closed by saying, “Can’t co-operate at the moment but would if it isn’t too like Merton of the Movies!”

Despite his high hopes and fine understanding of melo Hollywood, Bill Warren could not find a studio job or interest anyone in Tender Is the Night; he returned to New York and went to work writing detective stories for the pulps. Fitzgerald wrote Maxwell Perkins that “for a whole year” he had hoped for a financial “break in the shape of either Hollywood buying Tender or else… getting… someone else to do an efficient dramatization.” But the break had not come and the author thought that he knew why.

I know I would not like the job, and I know that [Owen] Davis who had every reason to undertake it after the success of [his Broadway version of] Gatsby simply turned thumbs down from his dramatist’s instinct that the story was not constructed as dramatically as Gatsby and did not readily lend itself to dramatization.

Perhaps Fitzgerald was remembering the problems he had had turning Tender Is the Night into a movie when he wrote in a short story called “Financing Finnegan”:

It was only when I met some poor devil of a screenwriter who had been trying to make a logical story out of one of his books that I realized he had his enemies.

“It’s all beautiful when you read it,” this man said disgustedly, “but when you write it down plain it’s like a week in the nuthouse. ”

At one point in Tender Is the Night, Nicole looks at Dick and thinks, “It was as though an incalculable story was telling itself inside him, about which she could only guess at in the moments when it broke through the surface.” The movie camera and the movie audience would have been in a position much Like Nicole’s: they would have missed the “incalculable story” because the camera, unlike the novelist, cannot probe inside the mind. But if the job of adapting Tender for the screen was likely to drive one crazy, it was not because of some flaw in the “fine writing” of the novel. Tender had never been intended as a dramatic novel; Fitzgerald was experimenting with something very different— the “psychological novel.”

The camera could not show the mind, but it had nonetheless to show something. So the collaborators, Fitzgerald and Warren, manufactured what they must have thought of as “movie action.” A lecture which Stahr gives the writer Boxley in The Last Tycoon more or less sums up what went wrong. Boxley had written a scene which began with a duel and ended with one man falling into a well so that he “has to be hauled up in a bucket.”

“Would you write that in a book of your own, Mr. Boxley?”

“What? Naturally not.”

“You’d consider it too cheap.”

“Movie standards are different,” said Boxley, hedging.

“Do you ever go to them?”

“No—almost never.”

“Isn’t it because people are always duelling and falling down wells?”

Yes, and falling off horses and tumbling down mountains in funiculars.

In 1938 a New York dramatist named Mrs. Edwin Jarrett wrote a dramatic version of Tender Is the Night which she hoped to see staged on Broadway. A carbon of her adaptation reached Fitzgerald in Hollywood shortly after a producer had rewritten a screenplay on which Scott had worked for months. “I want especially to congratulate you,” Scott wrote Mrs. Jarrett, “… on the multiple feats of ingenuity with which you’ve handled the difficult geography and chronology so that it has a unity which, God help me, I wasn’t able to give it.” Fitzgerald worried, however, about the handling of Dick Diver in the play. “I did not manage, I think in retrospect, to give Dick the cohesion I aimed at,” the author confessed, “but in your dramatic interpretation I beg you to guard me from the exposal of this. I wonder what the hell the first actor who played Hamlet thought of the part? I can hear him say, ’The guy’s a nut, isn’t he?’ (We can always find great consolation in Shakespeare.)” Fitzgerald noted that the play would have to “get by Broadway first,” but if it did, he assured the playwright that Robert Montgomery wanted to play Dick Diver in a film version. But the play never did get by Broadway—it never even got to it.

It was not until 1962, twenty-two years after Fitzgerald died a Hollywood failure, that his novel was finally made into a movie. It was released by 20th Century-Fox, for whom the author had once worked (they had fired him after a few weeks). Tender Is the Night starred Jennifer Jones as Nicole and Jason Robards, Jr., as Dick Diver. Jill St. John was Rosemary and Joan Fontaine played Baby.

***

In 1936 Edwin Knopf heard that Fitzgerald had fallen on what he calls “very evil days.” Since he wanted to help the author, whom he had met in France during the twenties, Knopf contacted Fitzgerald through H. N. Swanson, a Hollywood agent. That year the author’s income had fallen to a new low—$10,180. Moreover, his debts amounted to forty thousand. But when Knopf offered to pay Fitzgerald a thousand dollars a week to come to Hollywood as a screenwriter, Swanson said that he wouldn’t insult his client with peanuts.

Next: Chapter 6 A Yank at Oxford: Pictures of Words

Published as Crazy Sundays: F. Scott Fitzgerald In Hollywood by John Aaron Latham (New York: Viking P, 1971).