F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Work in the Film Studios

by Alan Margolies

Just before arriving in Hollywood in 1937, F. Scott Fitzgerald complained about his inability to write anything worthwhile. “For over 3 years,” he confessed, “the creative side of me has been as dead as hell.”[1] Despite this, he was highly confident that he could become a successful scriptwriter. To his daughter he wrote: “I must be very tactful but keep my hand on the wheel from the start—find out the key man among the bosses and the most malleable among the collaborators—then fight the rest tooth and nail until, in fact or in effect, I’m alone on the picture. That’s the only way I can do my best work.”[2]

Fitzgerald had worked in Hollywood for brief periods in 1927 and 1931. As on these previous occasions, he attempted to learn the technical end of film making. But this time he was far more serious about his work and devoted much more time to studying movies, reading books, and discussing the craft with other writers. Soon he perceived, as he wrote in a note for The Last Tycoon, that “pictures have a private and complex grammar.”[3] In addition, no longer would he, nor could he, participate as much in Hollywood social life as he had in the past. He found the work to be “hard as hell” and within a month had lost ten pounds[4]. At first film writing was appealing, “a sort of tense crossword puzzle game,”[5] and at times he seemed happy. Shortly, however, as in the past, he became aware of the realities of film making. Again he saw that many people were involved in each film and that the final product was usually the result of compromise. True, sometimes a director was able to enforce his own style upon a film, but this occurred infrequently. Like so many other film writers of the time Fitzgerald eventually gave in at least halfway. In 1939, no longer on contract to MGM, but merely freelancing now, he was to write to his daughter somewhat jocularly: “I’m convinced that maybe they’re not going to make me Czar of the Industry right away, as I thought 10 months ago. It’s all right, baby—life has humbled me—Czar or not, we’ll survive. I am even willing to compromise for Assistant Czar!”[6] A year later, however, while preparing Cosmopolitan, a script based on “Babylon Revisited,” he was extremely optimistic: once again, suggesting even that he might have the talent to become both writer and director of a film[7]. But this was only wishful thinking.

An examination of the scripts and notes in the Fitzgerald Papers at Princeton University suggests that Fitzgerald was not an exceptional scriptwriter. But this material does indicate that he worked seriously at his new craft. In addition, it provides insight into his methods, showing not only how he applied the newly learned film techniques, but also how he employed many of the procedures—the use of the dramatic curve, the awareness of the necessity to develop character dramatically, as well as others—that he used as a writer of novels and short stories[8].

Fitzgerald’s first film, A Yank at Oxford—the first made by MGM in its new studios in England—was, according to film critic. Bosley Crowther, “an appropriate film to symbolize the clasping of commercial hands across the sea.”[9] The story was to be about an American football hero who attends Oxford but feels disdain both for the English and the school. Later he learns to love Oxford, but, by this time, having admitted to a wrongdoing for which another student has been blamed, he is expelled. An MGM assemblage, including director Jack Conway, actors Robert Taylor and Lionel Barrymore, and actress Maureen O’Sullivan, was sent to England to join others hired there. A team of writers in the United States, however, wrote much of the script. During a two week period in July, 1937, Fitzgerald was brought in to make revisions and at least two of his scenes were included in the film when released[10].

He believed that one of the major flaws in the script was the lack of a dramatized incident clearly showing the motivation for the young American’s sudden shift in feeling towards Oxford. He asked: “Why does he grow to like Oxford? Something should be done or seen or experienced that makes him decent, just as the persecution made him bitter. We were going to show that, but never have. It was to ‘come out’ sometime but hasn’t. Even if it is touched on in the punt scene with Molly, it will only be told, not dramatized.”[11]

He also suggested several changes in the heroine’s character. She had been portrayed as “a thoughtful girl who doesn’t speak much but always with pith and even a certain cheerful acidity— except when in love which [had not] as yet happened.”[12] To illustrate these suggestions, he rewrote a number of the heroine’s scenes, prefacing one of them with this statement further justifying his revisions; “At present, Molly’s speeches are full of such things as seeing Lee [the American] and being ‘startled.’ Why? A moment ago, she had ‘poise’ and was a ‘definite personality.’ We are also assured she is ‘healthy.’ Later, she has such elaborate and meaningless speeches as ‘He puts things crudely but at least he has a proper regard for a woman.’ What human being ever talked like that?”[13]

The dialogue revisions in this scene made Molly much more outgoing. Fitzgerald, for example, suggested changing her initial statement to the American from:

I thought I’d have some coffee with you.

to:

Room for one more?

He also added coyness to her personality when he changed her answer to the American’s request to see her at Oxford. Originally she had replied:

Possibly. I'm a student there—St. Cynthia’s College.

Now she said:

If you want to be sure, you’d better come along with me right now.

These and other revisions, according to Fitzgerald, made Molly into “a more positive personality.”[14]

In a revision of the second half of the script, Fitzgerald retained two montages. This film device, a series of quick cuts which condenses time or contracts space and conveys a feeling of suspense, was similar in some ways to the juxtaposition of unrelated sentences in the drunk scenes in This Side of Paradise and The Great Gatsby. Fitzgerald, apparently fascinated by its effect, was to continue using it in The Last Tycoon, as well as in a number of later films.

The first version of the script of Three Comrades, his next project, for example, began with a typical Hollywood montage of the time:

1 fade in:

A GERMAN FLAG—

—surmounted by a magnificent bronze imperial eagle, waving against a white sky.

cut to:

2 A FRENCH SEVENTY-FIVE GUN----

—in action. It fires.

cut to:

3 THE FLAGPOLE-------

—newly split, the eagle gone, the shredded flag fluttering on the remnant of the pole.

dissolve to:

4 A CORNER OF A MILITARY WAREHOUSE—

—where a pile of rifles mounts rapidly higher as other rifles are laid upon it.

cut to:

5 A PILE OF GERMAN HELMETS----

—added to as other helmets are thrown upon it.

dissolve to:

6. TITLE

“during the nineteen-twenties while the world was prosperous THE GERMANS WERE A BEATEN AND IMPOVERISHED PEOPLE.”

DISSOLVE to:

7 EXT. OF A FOOD DEPOT; THE BEGINNING OF AN ENDLESS CUE OF PEOPLE---- …[15]

He even had a dream—with humorous overtones—related to his work with producer Joseph Mankiewicz in Three Comrades, revealing his concern with this technique. He jotted it down, possibly intending to use it in The Last Tycoon: “Dream of Joe M— 1050 word continuity, cost too much to type. Sorry[.] His face. He compliments me on other work. Too many montages—can’t afford them.”[16]

For awhile he enjoyed working on Three Comrades, a film based on Erich Maria Remarque’s novel about post-World War I Germany. The work was considered somewhat daring for Hollywood in 1937 because of its anti-Nazi sentiment, and Fitzgerald, who was becoming more politically aware, probably found this aspect appealing. It also contained a number of characters and situations familiar to him. The hero of this story about members of the lost generation was just thirty. The heroine had tuberculosis and at the end would die in a sanitarium. Even Remarque's philosophy at times probably seemed recognizable. At one point one of the characters in the novel delivers a speech reminiscent of some of the ideas in The Great Gatsby: “‘The most uncanny thing in the world, brothers, is time. Time. The monument through which we live and yet do not possess.’ He pulled a watch from his pocket and held it in front of Lenz's eyes. ‘This here, you up-in-the-air romantic. This infernal machine, that ticks and ticks, that goes on ticking and that nothing can stop ticking. You can stay an avalanche, a landslide—but not this.’”[17]

In structuring his script, Fitzgerald divided the film into acts— a method not too unusual for Hollywood writers, and similar to that which he had used at times in the past and was to use again in his plans for The Last Tycoon—superimposing them on the more usual sequence structure. In his first act, he introduced the three comrades, formerly members of the German Air Force and now attempting to survive the depression in their automobile repair shop; the girl, Pat; and her friend Breuer, soon to be a powerful Nazi-like political figure. By the end of this act, Pat has fallen in love with Bobby, the youngest of the three comrades. The second act includes the realization of their love, Pat’s slow physical deterioration because of tuberculosis, and the death of Lenz, another of the comrades, as a result of his anti-Nazi activities. In the third act, Pat, not wishing to be a burden to Bobby, commits suicide. The two remaining comrades then return to the city to fight for freedom.

Some of Fitzgerald’s visual devices, such as the opening montage and a double exposure at the end of the film showing the two comrades marching side by side with their dead friends, were effective. At another point, to contrast Bobby’s poverty with Breuer’s wealth, he again made satisfactory use of the visual by suggesting juxtaposed scenes, one showing Breuer preparing for a theatre date and then another showing Bobby’s preparations:

83 BREUER’S FACE—

—above a white tie he is adjusting in the mirror. A butler is snapping a buckle on his smooth vest.

cut to:

84 A LARGE SAFETY PIN--------

—on a very gaping vest. This is upon Bobby who is in his room, being valeted by Koster and Lenz. There are open suitcases of clothes on the floor.

(P. 54)

Yet another effect, a trope showing Bobby’s extreme shyness as he makes his way to his first date with Pat, is similar in some ways to the description of Jay Gatsby walking into Nick Carraway’s bungalow “as if … on a wire”[18] as well as to the later description of Boxley, the English writer in The Last Tycoon, nervously coming into a room, walking “as if two invisible attendants”[19] were controlling him:

60 THE HALL OF AN APARTMENT HOUSE

(The following scene is an attempt to suggest the feelings of a rather shy young man calling on a girl).

Bobby walks with leaden, slow-motion steps into the elevator. To his alarm, it instantly whisks upward with a roar—almost as its gates close they open again to eject him. He casts a reproachful look at the elevator boy. Must he continue? Unseen hands seem to push him from behind, so that he leans backward in protest against the shoving. But the door opens even as he presses the bell and, following a maid, he is shoved like lightning along a hall. The hands seem to leave him, and he stands, limp, inside.

(P. 33)

Other metaphors, however, were far too fanciful for the theme of the film and, in addition, somewhat trite. He suggested, for example, that Bobby's first reaction to Pat could be symbolized by showing her phone number on a match cover wriggling “like snakes or tongues of fire, as if it ha[d] been burning his pocket” (p. 29). Immediately after, when Bobby makes his phone call from a noisy repair yard, Fitzgerald used an even more inappropriate film trope by placing angels and satyrs at the switchboard. In addition, the dialogue is uncomfortably precious:

Bobby waits for the connection with a beatific smile. The banging dies away as we—

cut to:

54 a switchboard—

—with a white winged angel sitting on it.

Angel (sweetly)

One moment, please—I’ll connect you with heaven.

cut to:

55 the pearly gates

St. Peter, the caretaker, sitting beside another switchboard.

St. Peter (cackling)

I think she’s in.

cut to:

56 bobby’s face

—still ecstatic, changing to human embarrassment as [Pat answers.]

(P. 29)

Elsewhere there are other sections of ineffective dialogue. Earlier, when the three heroes fight the Vogt brothers, four owners of a competing automobile repair shop, the writing again becomes overly metaphoric:

21 KOSTER AND LENZ----

—approaching [a] wreck.

Biggest Vogt (to Bobby)

Don’t talk tripe or you’ll need repairs yourself.

Koster and Lenz range themselves beside Bobby.

Koster

We’ve got permission from the owner to do the job.

Another Vogt Brother

(producing a tire wrench from behind his back)

How would you like another scar on your fat face?

Koster

That took a machine gun.

Biggest Vogt (still sure of himself)

Three of you, eh?

Lenz

No, four.

Another Brother (looking around)

Go on—he’s kidding.

Lenz (dryly)

You can’t see him—his name is Justice.

(P. 7)

Later, Fitzgerald ended his first act with a scene in which Pat and Bobby, riding in a flower wagon, tenderly discuss their new relationship and Pat alludes to her illness. Unfortunately, he permitted the conversation to continue until the scene became embarrassing:

Bobby

You really don’t love me, do you?

Pat (shaking her head)

No. Do you love me?

Bobby

No. Lucky, isn’t it?

Pat

Very.

Bobby

Then nothing can hurt us.

Pat

Nothing.

Bobby

(puts his arm around her with a passion that belies his words)

But you’d better not get lost in here, because I’d never be able to pick you out from the other flowers.

His arm around her—she lies closely to him.

Pat

I’m not this kind of flower. I’m afraid I’m the hothouse variety.

(she picks up a blossom and addresses it rather sadly)

I’d love to be like you, my dear.

Bobby

(holding her close to him; passionately)

Oh you are—you are!

(pp. 52-53)

When he rewrote the scene, Fitzgerald sensibly cut it short and ended it when Bobby puts his arm around Pat.

Years later, producer Mankiewicz criticized Fitzgerald’s script. “I personally have been attacked,” Mankiewicz said, “as if I had spat on the American flag because it happened once that I rewrote some dialogue by F. Scott Fitzgerald. But indeed it needed it! The actors, among them Margaret Sullavan, absolutely could not read the lines. It was very literary dialogue, novelistic dialogue that lacked all the qualities required for screen dialogue. The latter must be ‘spoken.’ Scott Fitzgerald really wrote very bad spoken dialogue.”[20] Although it is obvious that some of Fitzgerald’s dialogue was not too effective, this first version of Three Comrades does not seem to deserve Mankiewicz’ overly harsh statement.

Fitzgerald wanted to work alone on the revision of the script and Mankiewicz hinted that this might be possible.[21] Later, however, he brought in Ted Paramore, an old friend of Fitzgerald, to assist the novelist. Fitzgerald soon quarreled with Paramore over the latter’s function (once, according to Fitzgerald, despite his opposition, Paramore wanted to rewrite the entire script),[22] but eventually the relationship improved. The collaborators strengthened the script, revising much of it, and when the film was produced Paramore received credit (with Fitzgerald) as co-author.

Mankiewicz, however, made many changes in this second script, and, by mid-January, Fitzgerald was expressing his displeasure with his producer’s version. Paramore agreed that some scenes had been changed for the worse.[23] On the cover page of his copy of the final script, Fitzgerald crossed out “okayed” in the statement “Script okayed by Joseph Mankiewicz,” and immediately above wrote “Scrawled Over.” On the next page he wrote, “37 pages mine [,] about 1/3, but all shadows & rythm [sic] removed.”[24] In a letter to Mankiewicz he complained that his writing had been completely changed. “My own type of writing,” he wrote, “doesn’t survive being written over so thoroughly and there are certain pages out of which the rhythm has vanished.”[25]

Nonetheless, he did accept some of the producer’s revisions. Others, though, angered him. He objected to the elimination of a number of scenes and wrote that Mankiewicz had changed Pat’s character and had transformed her into “a sentimental girl from Brooklyn.”[26] He disliked as well the slickness of lines such as those spoken immediately after Erich’s (the name had been changed) return from his date with Pat, in the course of which his borrowed, makeshift evening clothes have come apart:

89 INT. ALFONS’ BAR

Lenz and Koster at a table as Erich comes in. They are surprised

Koster

Hello, Cinderella—got both your slippers on?

Erich

(calling off)

Alfons—a double rum!

Lenz

What happened?

Erich

Nothing. At sharp midnight I changed back into a garage mechanic, that’s all—

(P. 57)

What is more, he advised Mankiewicz, who had had years of script-writing experience, how to write film dialogue. Concerning a speech beginning, “—if all I had,” he wrote: “People don’t begin all sentences with and, but, for and if, do they? They simply break a thought in mid-paragraph, and in both Gatsby and Farewell to Arms the dialogue tends that way. Sticking in conjunctions makes a monotonous smoothness.”[27]

But Mankiewicz had the final word and the picture was made his way. The emphasis of the film was now on the love theme. Much of the original anti-Nazi theme, including a number of strong references to German anti-Semitic attitudes, was deleted. Even the ending, where originally the two remaining comrades return to fight the Fascists, was changed. Now they were to leave for South America, apparently resigned to a life of withdrawal.

“I think you now have a flop on your hands,” Fitzgerald wrote the producer, “—as thoroughly naive as The Bride Wore Red [a previous Mankiewicz production] but utterly inexcusable because this time you had something and you have arbitrarily and carelessly torn it to pieces.”[28] But at least some of the reviewers reacted favorably. Frank Nugent in the New York Times, for example, called Three Comrades “a beautiful and memorable film” and praised it as “magnificently directed, eloquently written and admirably played.” Nugent not only paid tribute to Fitzgerald and Paramore but also singled out director Frank Borzage (whom Fitzgerald had said “had little more to do than be a sort of glorified cameraman”[29]) for acclaim. “The adaptation by F. Scott Fitzgerald and Edward E. Paramore,” Nugent wrote, “has kept Remarque’s language, kept his characters, kept the slight but telling incidents the novel contained. And Frank Borzage, who directed it, has achieved once more the affecting simplicity that marked his ‘Seventh Heaven’ (silent version) and ‘Farewell to Arms.’ His cameras have evoked the tender mood, wooed the lovers in their wooing, imprisoned in swift bright images their helplessness and hopelessness and their ultimate brave triumph over death itself.”[30] Later, Paul Rotha, in his analysis of Borzage’s work in The Film Till Now, wrote that Three Comrades was “immeasurably superior”[31] to the later wartime anti-Nazi films. Apparently, at least some of Fitzgerald’s criticism of Borzage— and possibly Mankiewicz—was unwarranted.

Next, Fitzgerald worked with MGM producer Hunt Stromberg on Infidelity, a film intended for Joan Crawford. “This time I have the best producer in Hollywood,” the novelist exclaimed, “a fine showman who keeps me from any amateur errors.”[32] Stromberg, a ranking MGM supervisor in the 1920s and early 1930s, was, according to Fitzgerald, “a sort of one-finger [Irving] Thalberg, without Thalberg’s scope, but with his intense power of work and his absorption in his job.”[33]

The script for Infidelity was based on Ursula Parrott’s short story about a young wife, Althea Gilbert, who returns from Europe to discover her husband, Nicholas, having a brief affair with an old girl friend. Immediately Althea asks for a divorce but soon thinks better of her action when she realizes how much her husband means to her. Before her marriage she had been deeply in love with a young man who had turned out to be disreputable, and, almost immediately, upon the advice of her grandmother, had married Nicholas. Soon after she almost had been enticed into an affair with the boyfriend, but decided against it. Later, after requesting the divorce, she once again sees the boyfriend and discovers he is as much of a bounder as he had been in the past. At this point she is both grateful to and in love with Nicholas and forgives him, realizing that in a similar situation she, too, could easily have been tempted.[34]

Early in February, 1938, Stromberg and Fitzgerald decided on a plot that differed in a number of ways from Mrs. Parrott’s story. The film was to begin two years after the act of adultery with Althea and Nicholas still together, but weary of each other and not living as man and wife. A flashback was to reveal an adulterous situation somewhat different from the original story. According to Stromberg, Iris Jones, the third party, was to be portrayed as one whom Nicholas, in the past, might have married as readily as his own wife, and the act of adultery was to be the result of an innocent accident, a mere circumstance that was to develop into a tragic situation.[35]

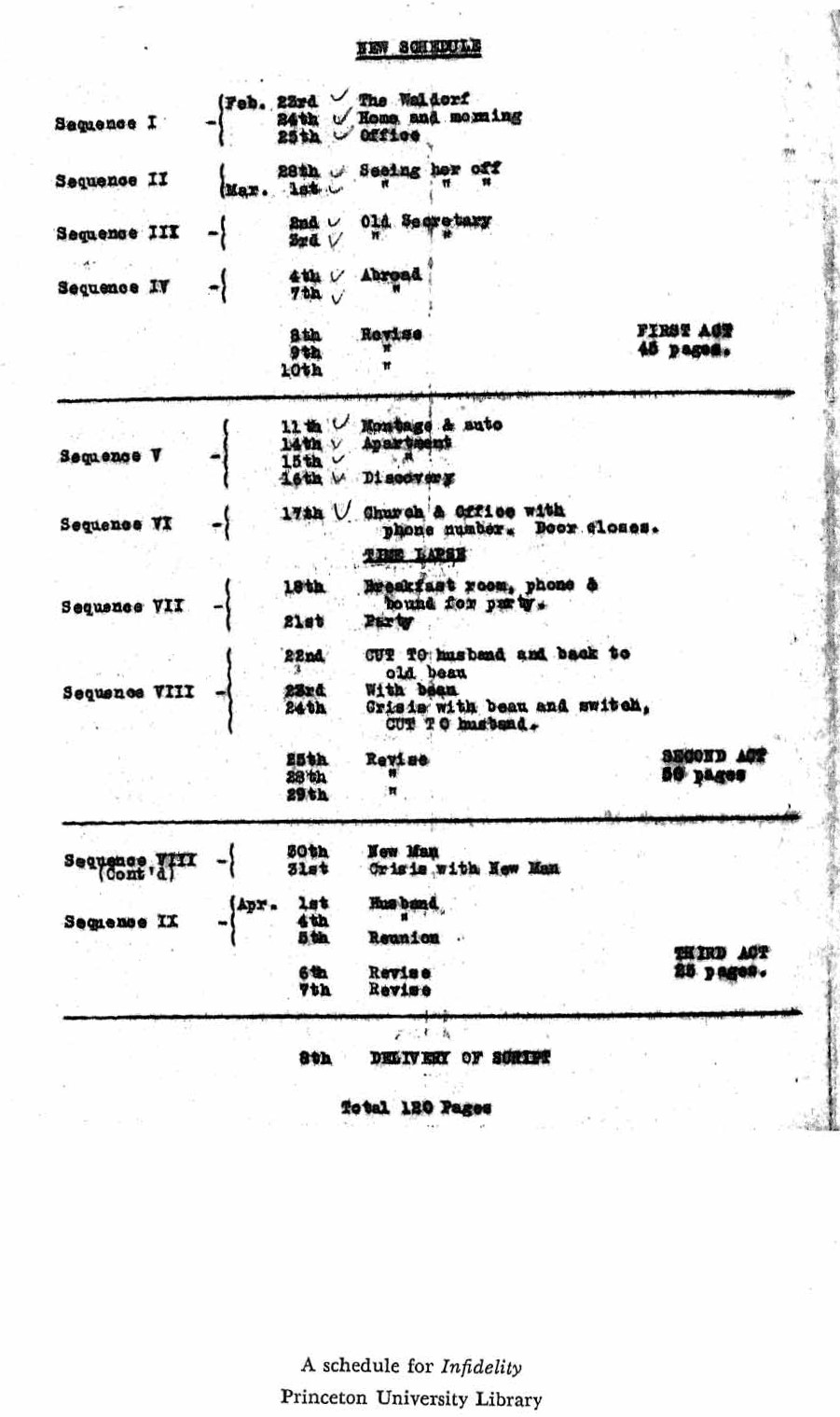

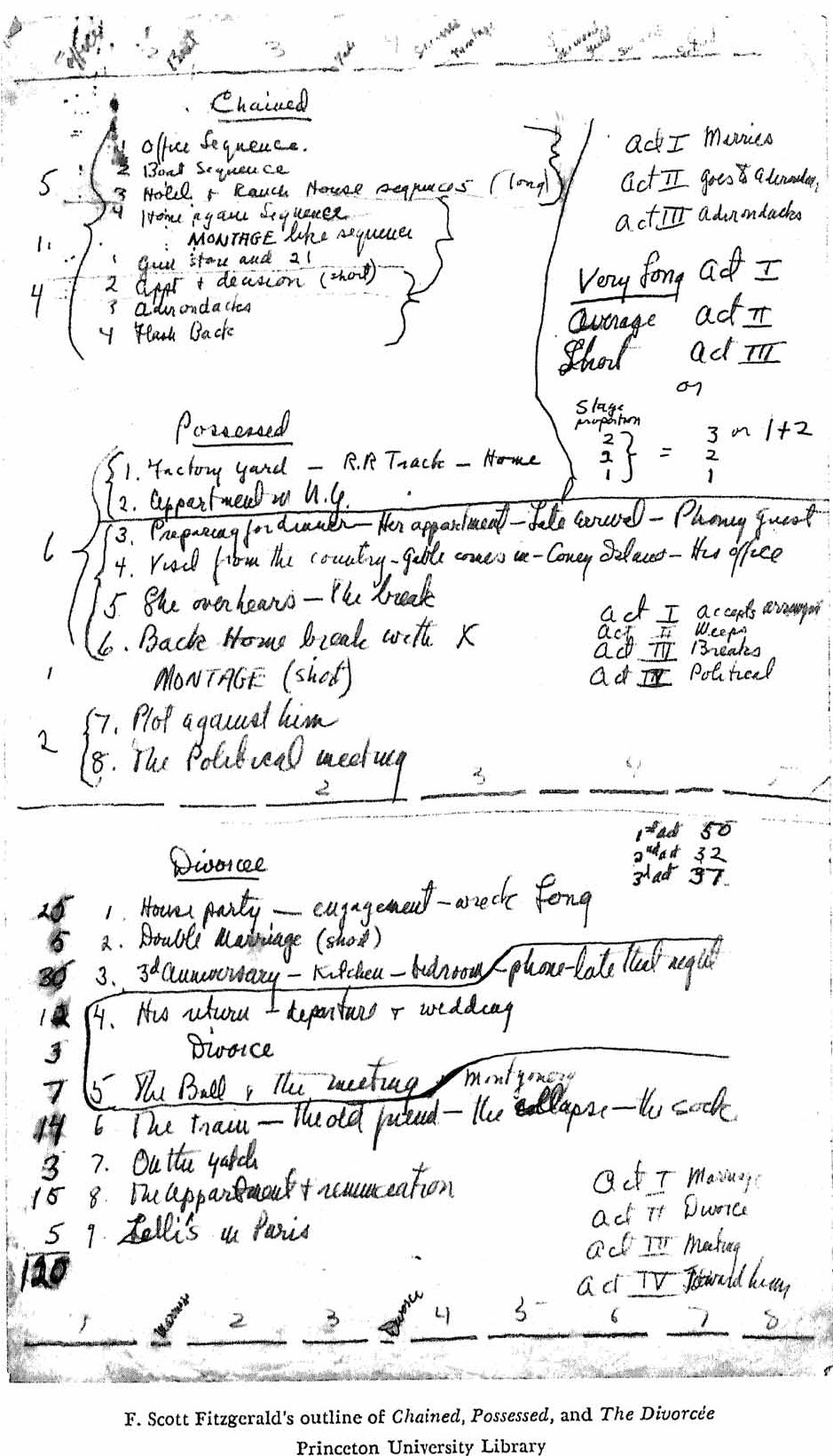

In preparation, Fitzgerald ran off a number of Miss Crawford’s films and, hoping to write a script that would display her capabilities, jotted down her weaknesses and strengths. In addition, he outlined the plots of three films, The Divorcee (1930), Possessed (1931), and Chained (1934), the last two featuring Miss Crawford and all dealing with a similar theme. In his outlines, Fitzgerald divided each film into major sequences, paying particular attention to montages. Then he broke down the films into acts and, for The Divorcee, indicated the number of pages of script per act. He made a similar but more detailed plan for Infidelity. On the left side of the page he numbered nine sequences; in the center he described scenes in detail and indicated dates of completion of work; and on the right side he divided the film into three acts and estimated the number of pages per act.[36]

In a memorandum to Stromberg, he referred to this theatrical method: “The first problem was whether, with a story which is over half told before we get up to the point at which we began, we had a solid dramatic form—in other words whether it would divide naturally into three increasingly interesting ‘acts’ etc. The answer is yes—even though the audience knows . . . that the characters are headed toward trouble.” Following Stromberg’s suggestions, Fitzgerald’s first act showed the couple’s present bored state, and then, in a flashback, Althea’s trip to Europe where she meets Alex Aldrich, an old boyfriend (not at all like the suitor in the original short story), but decides to return immediately to the United States and to Nicholas. “This point, her decision to sail,” Fitzgerald wrote, “also marks the end of the ‘first act.’ The ‘second act’ will take us through the appartment [sic] scene [where Althea confronts Iris and Nicholas], the two year time lapse and the return of [Alex] the old sweetheart—will take us, in fact, up to the moment when Joan having weathered all this, is unpredictably jolted off balance by a stranger. This is our high point—when matters seem utterly insoluble.” Further, he wrote, “Our third act is Joan’s recoil from a situation that is menacing, both materially and morally, and her reaction toward reconciliation with her husband.”[37]

In Fitzgerald’s script Alex’s second act return is precipitated by Althea’s mother who asks him to “run away with [Althea] if she’ll run—beat her, make love to her, wake her up.” [38]Althea, however, unable to marry or even have an affair with Alex, flees and ends up in the arms of an attractive doctor near her Long Island home where, unknown to her, Nicholas is giving a party. Although all available scripts at Princeton University Library are incomplete, the writer’s notes indicate a happy ending with Althea and Nicholas together once more.

Fitzgerald again wrote in a number of visual effects. Following Stromberg’s suggestion, he kept the camera stationary throughout the last half of the first scene despite the fact that emphasis was being placed on activity both in the foreground and in the background, a technique soon to be popularized in Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. In this same scene Fitzgerald indicated Althea’s boredom by having her turn her wedding ring with her thumb and by asking for a closeup of her passive mask-like face. At another point he called for contrasting montages, one showing early scenes of a happy couple and another, later in the script, showing parallel scenes of the couple, now unhappy.

Fitzgerald’s dialogue, however, was still uneven, some of it more than acceptable, but some wordy and overly sentimental. One important scene before the affair, showing Althea deeply in love with Nicholas and dreading to leave for Europe, reflects this variable quality:

Althea (leaning over table)

I don't believe I’m going away. I never have believed it and I never will. If you were leaving me, I could understand it—but that I'm going away free and in my right mind—

(she shakes her head somberly from side to side)

Nic[h]olas

You’re not going away. Listen, did you read in the papers about the dog they froze up in a cake of ice—

Althea

Poor dog.

Nic[h]olas

Wait a minute—

Althea (near tears anyhow)

I’m afraid I’m going to weep over that dog.

Nic[h]olas

Wait! They thawed him out after a month, and he came to life again. That’s how it’ll be with us.

Althea

But what’ll I think about in my cake of ice?

Nic[h]olas

Oh, you look out and see the Italian scenery and watch your mother get well and write me letters.

(pp. 18-19)

Yet, Fitzgerald might have received his second screen credit had not he and Stromberg run into censorship difficulties—for the plot dealt too easily with adultery. Probably recalling his work in 1931 on the script for Red-Headed Woman, a film that treated adultery in a light vein, Fitzgerald described the situation to his daughter: “We have reached a censorship barrier in Infidelity to our infinite disappointment. It won't be Joan’s next picture and we are setting it aside awhile till we think of a way of halfwitting halfwit Hayes and his Legion of Decency. Pictures needed cleaning up in 1932-33 (remember I didn’t like you to see them?) but because they were suggestive and salacious. Of course the moralists now want to apply that to all strong themes— so the crop of the last two years is feeble and false, unless it deals with children.”[39]

From this point on, Fitzgerald and Stromberg made many attempts, without success, to salvage the script. At one time, for example, Fitzgerald wrote out a list of scenes from the 1938 film Test Pilot and placed them side by side with the scenes from Infidelity, but he was unable to find a parallel to the successful ending of Test Pilot[40]. At another time he thought of dramatizing a situation where each character would be placed in the role of another. Thus Althea might forgive Nicholas if she could fully imagine herself: as Iris Jones. He was trying to sell the idea to Stromberg when he wrote the following:

Let us suppose that you were a rich boy brought up in the palaces of Fifth Avenue.

Let us suppose that—and I was a poor boy born on Ellis Island.

Let us suppose that’s the way it was—you a rich boy—me a poor boy, get me?

Well, now, me the poor boy has done a bad thing and I am going to tell you, a rich boy, how it happened, and I am going to say to you:

“Picture yourself in my place.”[41]

A similar situation was to occur later in The Last Tycoon when the novelist Boxley, working on a script problem, suddenly is inspired. He tells producer Stahr: “Let each character see himself in the other’s place… The policeman is about to arrest the thief when he sees that the thief actually has his face. I mean, show it that way. You could almost call the thing Put Yourself in My Place” (p. 107). But there is more hope for Boxley’s idea than there was to be for Fitzgerald’s.

By the end of April, Fitzgerald and Stromberg were considering a radical change in the script, intending to place greater emphasis on the divorce. Althea was to marry Alex, the old boyfriend, but, after a long period of unhappiness for both Althea and Nicholas, the Gilberts would be reunited. In working out this problem Fitzgerald drew upon his background in both theatre and fiction. He diagrammed a ten-year interval after the divorce, and, considering the film as if it were a novel, wrote: “This is a novel in which I show 1st a glimpse of an estranged couple[;] 2nd How it happened[;] 3d Their decision, precipitated by an old love of hers, to get a divorce.” At another time he made a diagram of this ten-year period, divided it into five parts and a conclusion, and referred to each section as “A One Act Play.”[42] During the middle of May, he once more was examining other film scripts and even relying on Georges Polti’s Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations. “Now the question arises,” he wrote, “as to whether we have a theme here to place beside the themes of, say, chained, possessed and divorcee, all dealing with the subject of adultery. The answer is we have not and cannot according to the state of the censorship. What we have is the story of a man who was unfaithful to his wife and who, years later in trying to protect her from another such experience, wins her back again. Or, from a woman’s angle, fidelity [a change in title had been suggested] is the story of a woman’s faithfulness to the ideal of chastity which is finally rewarded.”[43]

Fitzgerald and Stromberg continued to correspond at least until the middle of July, and each made many attempts to solve the impasse. Once Fitzgerald even considered punishing Nicholas either by imprisonment or death but nothing came of this or any of the other suggestions. In May he had begun to work on another film, and soon he and Stromberg gave up on the script.

The following year Fitzgerald admitted that he may have been at least partly responsible for the failure of Infidelity. To Leland Hayward he wrote that Stromberg “liked the first part … so intensely that when the whole thing flopped I think he held it against me that I had aroused his hope so much and then had not been able to finish it. It may have been my fault—it may have been the fault of the story but the damage is done.”[44]

Next Fitzgerald worked under Stromberg for a short period on Marie Antoinette. His papers include a five-page carbon typescript with corrections in his hand of the scene in which Marie (played by Norma Shearer) bids farewell to Count Axel de Fersen, her lover (played by Tyrone Power). Apparently Fitzgerald’s contributions to the film, if any at all, were minor and, according to Sheilah Graham, he soon “was replaced as usual by another writer in the Metro stable of highly paid puppet authors.”[45] After Marie Antoinette, he worked for a brief period again under Stromberg, but now also with director Sidney Franklin and writer Donald Ogden Stewart, on an adaptation of Clare Boothe’s play The Women. Fitzgerald thought the film belonged in the tradition of the 1932 MGM classic Grand Hotel, a movie with many stars and with plot emphasis divided among several major characters. One of the difficulties faced by the scriptwriters, who were closely following the play, resulted from the decision to include no men in the story. Fitzgerald paid particular attention to this problem. His treatment also reflected his wariness of film cliches, a subject that he would return to several times in the Pat Hobby stories. Of one scene in The Women showing the publication of a piece of gossip, Fitzgerald wrote: “The story is printed—we see it being typed in a newspaper office. But certainly we don’t have that hackneyed old stock montage of the presses turning.”[46]

After The Women, Fitzgerald, once again working with Sidney Franklin and using the script of the 1934 MGM film The Barretts of Wimpole Street as a model, wrote a script based on Eve Curie’s biography of Marie Curie. Like The Barretts, Madame Curie, at least at first, was to be the story of a courtship and was to exclude everything after the marriage. “Madame Curie progresses,” he wrote his daughter, “and it is a relief to be working on something that the censors have nothing against. It will be a comparatively quiet picture—as was The Barretts of Wimpole Street, but the more I read about the woman the more I think about her as one of the most admirable people of our time. I hope we can get a little of that into the story.”[47] Fitzgerald completed the script, but the project was put aside temporarily because of a disagreement over his conception of the story.[48]

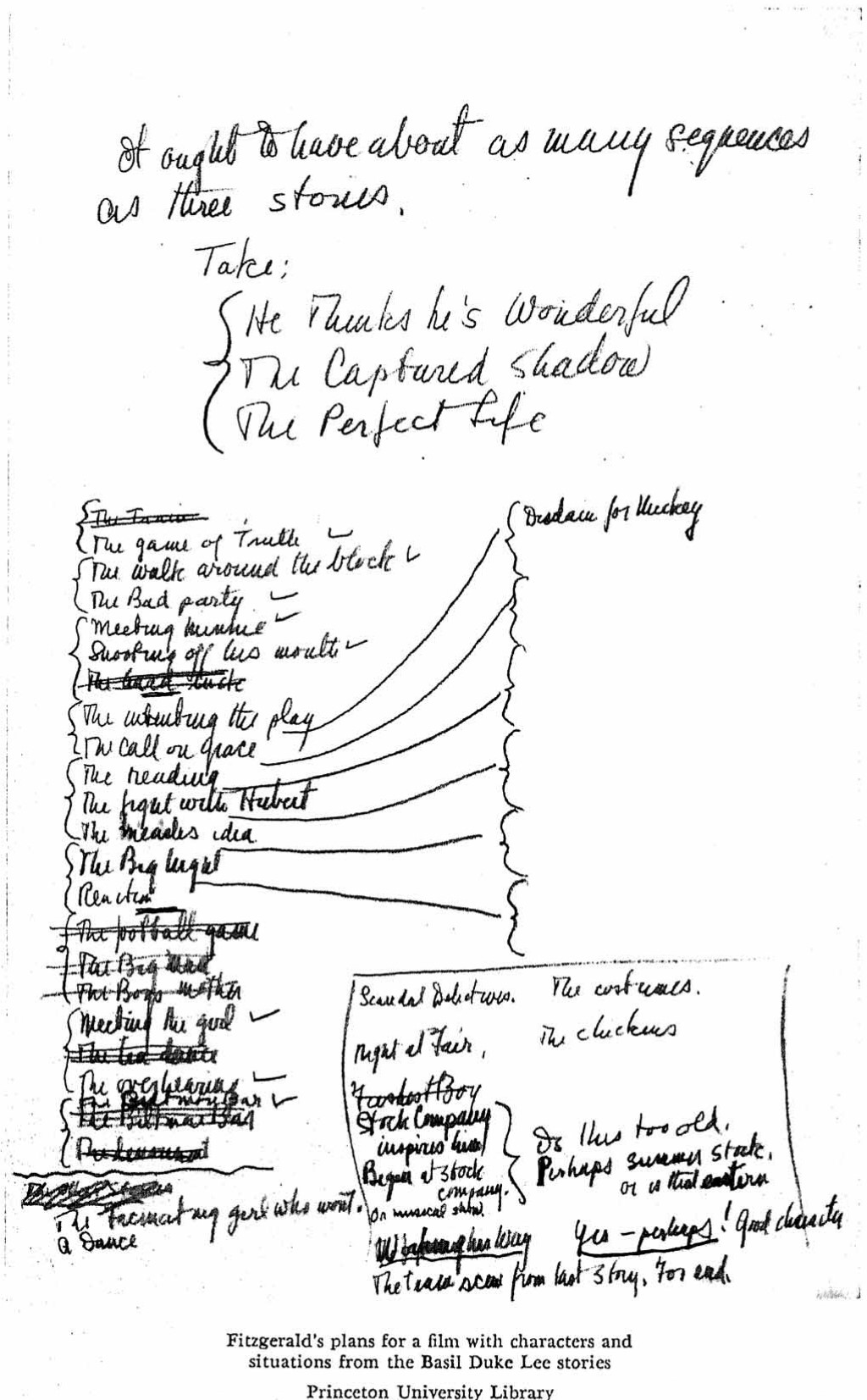

During this period Fitzgerald, in addition, was submitting plot ideas to MGM with the hope that he would be permitted to work alone on a script, but none was acceptable. One of these suggestions, a story about an amateur theatre group, was planned for three youthful MGM stars, Mickey Rooney, Judy Garland, and Freddie Bartholomew. The plot, though not specifically based on Fitzgerald’s early experiences in St. Paul or on his Basil Duke Lee stories derived from them, would have contained situations like those found in three of the stories, “He Thinks He’s Wonderful,” “The Captured Shadow,” and “The Perfect Life.”

In Fitzgerald’s brief treatment, a bright young Freddie Bartholomew-type adolescent writes a play and the Mickey Rooney character plays the lead. A number of complications such as cast trouble, illness, and the lack of money threaten to end the venture, but, eventually, with the help of a rich young girl, the Judy Garland character, the necessary money is raised. The subplot was to be about the love interests of the young woman who chaperones the group.

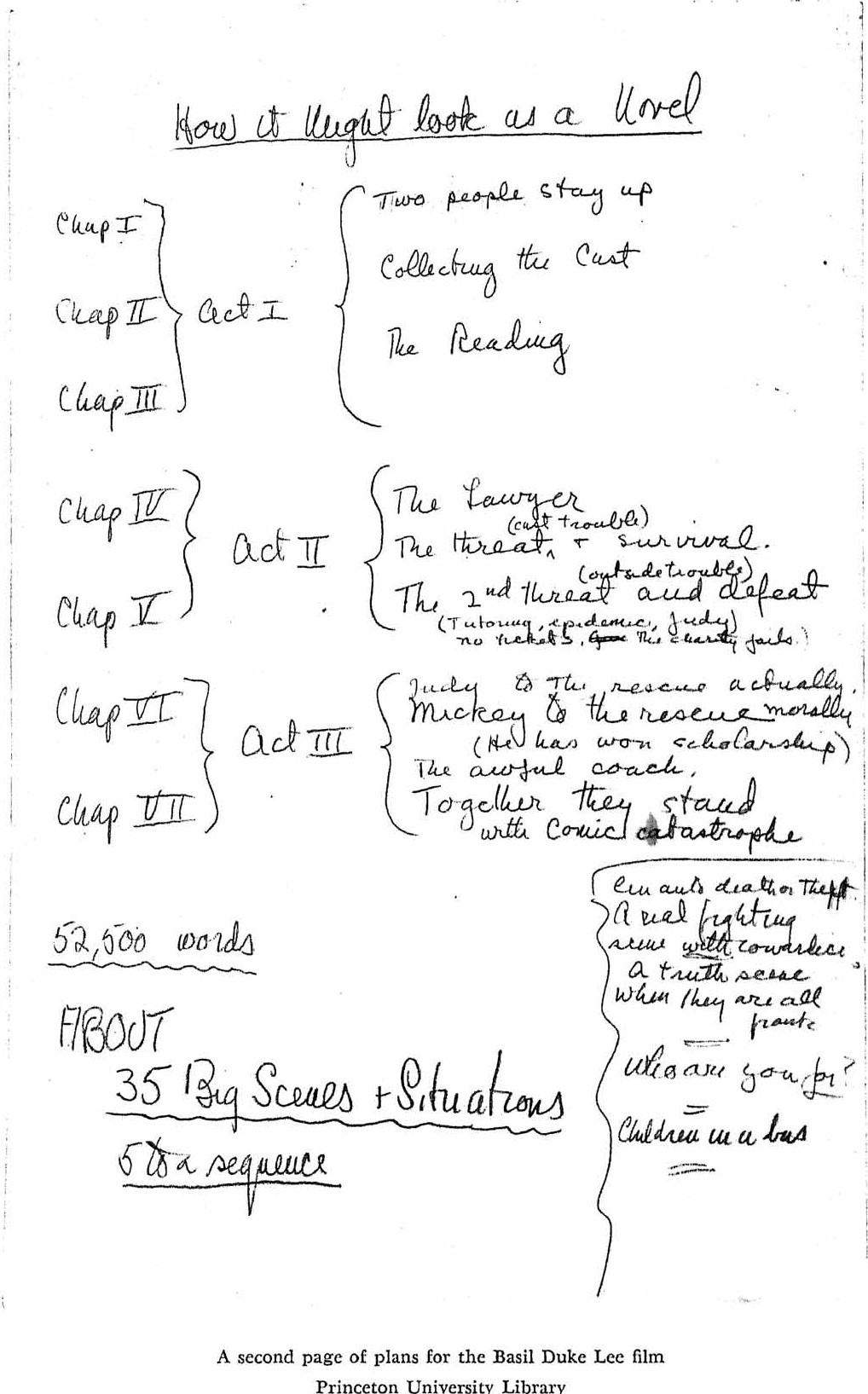

In his diagrammed plans for the movie, Fitzgerald once more used his background as a novelist and playwright. In one diagram he listed a number of situations from the Basil stories and wrote at the top of the page, “It ought to have about as many sequences as three stories.” He headed another plan, “How it Might look as a Novel.” On the left side of the page he divided the plot into seven chapters and below wrote “52,500 words”; in the center of the page he divided the plot into three acts; on the right side of the page he divided it into sequences. At the bottom of the page he wrote, “About 35 Big Scenes & Situations 5 to a sequence.”[49]

Finally, in January, 1939, he did some two weeks of rewriting on the Gone with the Wind script for Selznick International Productions, apparently making a minimal contribution to a mammoth production that would use the service of many writers including Sidney Howard (who was to receive credit for the screen play), Ben Hecht, Charles MacArthur, and John Van Druten.[50] This was another frustrating project for him. He had just read Miss Mitchell’s novel and found it “not very original, in fact leaning heavily on The Old Wives' Tale, Vanity Fair, and all that has been written on the Civil War.” Further, he wrote: “There are no new characters, new technique, new observations—none of the elements that make literature—especially no new examination into human emotions. But on the other hand it is interesting, surprisingly honest, consistent and workmanlike throughout, and I felt no contempt for it but only a certain pity for those who considered it the supreme achievement of the human mind.”[51] Yet, despite these negative feelings about the work, he was required to adhere closely to Miss Mitchell’s style. He later wrote Maxwell Perkins, “Do you know in that Gone with the Wind job I was absolutely forbidden to use any words except those of Margaret Mitchell; that is, when new phrases had to be invented one had to thumb through as if it were Scripture and check out phrases of hers which would cover the situation!”[52] Fitzgerald’s script with its pointed references to specific pages in the novel seems to bear out the statement.

After MGM decided against renewing his contract, Fitzgerald worked with writer Budd Schulberg on Walter Wanger's production of Winter Carnival. Upon completion of some preliminary work in Hollywood, the two went with the production crew to Dartmouth College where background footage of the college winter carnival was to be filmed. After a few weeks Fitzgerald, ill and drinking heavily, was fired. When finally released, Winter Carnival retained only the slightest relationship to the version upon which the novelist had been working.[53]

Later, while jotting down notes for an early version of The Last Tycoon, Fitzgerald considered employing his experiences at Dartmouth with the Winter Carnival crew for an episode late in the novel. Warning himself to avoid problems of infringement, he wrote:

I would like this episode to give a picture of the work of a cutter, camera man or second unit director in the making of such a thing as Winter Carnival, accenting the speed with which Robinson works, his reactions, why he is what he is instead of being the very high-salaried man which his technical abilities entitle him to be. I might as well use some of the Dartmouth atmosphere, snow, etc., being careful not to impinge at all on any material that Walter Wanger may be using in Winter Carnival or that I may have ever suggested as material to him.[54]

But then he went on to suggest a sequence in which he seemed to be using some elements of his Winter Carnival treatment. In an opening scene in the film treatment, a glamour girl, fleeing her husband, stays through the carnival. Upon her arrival at the college, she gets off the train, and, to evade photographers, goes into the station telegraph office. Here she meets a former boy-friend, now a professor, who conceals a telegram that he is sending in response to a job offer. In the early plan for The Last Tycoon Fitzgerald wrote: “I could begin the chapter through Cecelia’s eyes, who is [the narrator and] a guest at the carnival, skip quickly to Robinson and have them perhaps meet at a telegraph desk where she sees him sending a wire to Thalia [producer Stahr’s girlfriend].”[55]

In the spring of 1939, Fitzgerald worked for a period at Paramount Pictures for producer Jeff Lazarus on a film called Air Raid. Soon, however, the film was cancelled and he was released. At the end of the summer of 1939 he worked one week for Universal Pictures writing Open that Door, a brief treatment of Charles Bonner’s novel Bull by the Horns. In September he was hired for a week or so for the Samuel Goldwyn production of Raffles, ironic considering that as a youngster some twenty-seven years earlier in St. Paul, he had written and acted in The Captured Shadow, another work about a gentleman burglar. The film was involved in minor censorship difficulties, and he was asked to help solve these problems and to make other minor script revisions as well.[56]

At about this same time he worked one day for Twentieth Century-Fox on a film starring Sonja Henie and made a few plot suggestions, but none were used. His papers do not indicate the title of the movie but his copy of the script of Everything Happens at Night—a film starring Miss Henie and released at the very end of the year—contains a number of handwritten comments again demonstrating his dislike of the obvious. Noting a similarity in title to Frank Capra’s memorable film comedy of 1934, It Happened One Night, he wrote on the title page “ (Imitative Title) Is it deliberate?” A scene in which a man wants to fight a goggled skier who is eventually unmasked as a pretty girl was labeled “Old Ski Stuff.” Next to a scene in which one person shows another a newspaper story and says, “See that article! It’s dynamite,” he wrote, “And then you see.” He also singled out such trite dialogue as that in a scene where a man attracted to a nurse says: “It must be nice being a nurse . . . You know, I’ve never been sick a day in my life—but I could start right now.”[57] By this time Fitzgerald could do an adept job at criticizing another writer’s script. But he was to fail when finally given the opportunity to be sole author of one.

In January, 1940, he sold the rights to “Babylon Revisited” to Lester Cowan of Columbia Pictures and two months later Cowan hired him to write the script, first called Honoria, then Babylon Revisited, and, finally, Cosmopolitan. Cary Grant, Clark Gable, and Franchot Tone were all mentioned for the role of Charles Wales, and Shirley Temple was to play the role of the daughter, named Honoria in the short story and in the first version of the script, but renamed Victoria in the final version. Casting problems soon arose, however, and the script was set aside in the early fall.[58]

Cosmopolitan differed greatly from its source. It did not contrast the frenzied twenties with the more austere thirties; nor did it retain the mood of loss and emptiness caused by the end of an era and symbolized in “Babylon Revisited” by the death of Helen Wales. Instead, the script was a trite melodrama that included suicide, embezzlement, a love affair between Charles Wales and his nurse, and an attempted murder. The scant amount of dialogue retained from the short story only serves to remind the reader how much better the original was.

In his opening sequence, Fitzgerald established Victoria Wales as a far more important character than her prototype in “Babylon Revisited.” Eleven-year-old Victoria is seen traveling alone and without sufficient funds, attempting to make her way from Paris to Switzerland. Using a flashback, Fitzgerald then returned to a period some six months earlier when Victoria and her parents were leaving the United States for an extended vacation. Charles Wales has retired from the stock market partly because of fatigue and partly because of his wife’s nervous condition, an illness aggravated by his many business activities. Aboard ship, Helen Wales commits suicide and her husband immediately becomes depressed and takes to liquor. In Europe Wales’s unethical partner, Dwight Schuyler, with the help of a canny doctor, induces a drugged Wales to assign the guardianship of Victoria and a trust fund to Marion Petre, Helen Wales’s sister, and to Marion’s ineffectual French husband, Pierre. Later Pierre naively signs over the trust fund to Schuyler who invests it to cover market losses. Wales, with the help of nurse Julia Burns, soon recovers his health, but he fails to regain his daughter because, as in the original story, Marion Petre believes him responsible for his wife’s death. He then discovers that the evil Schuyler already has invested and lost a large sum belonging to Wales which was supposed to have been placed in Liberty Bonds. To recover his losses, Wales goes to Switzerland to get help from a potential backer named Van Greff. At this point, Fitzgerald, returning to the end of the first sequence, showed Victoria finally catching up with her father. He also introduced a murderer who had been hired by Schuyler to kill Wales for the million dollar insurance policy on Wales’s life. At the end of the story Van Greff dies unexpectedly. But Wales, who refuses to be defeated, subdues the killer, wins back his daughter, and apparently will marry Miss Burns.

Despite Fitzgerald’s “Author’s Note” stating that Cosmopolitan was “an attempt to tell a story from a child’s point of view without sentimentality,” this script, too, contained many sentimental scenes and much sentimental dialogue. At one point, the ill Wales and his daughter have an extremely teary farewell in a scene almost as fraught with Oedipal complications as the scene in Tender Is the Night in which Dick Diver, viewing Daddy's Girl, “winced for all psychologists”[59] because of the girl’s obvious father complex:

VICTORIA

Mr. Schuyler, can I say goodbye to Daddy?

SCHUYLER

But you did, dear.

VICTORIA

That wasn’t goodbye. That wasn’t anything at all.

Schuyler and Dr. Franciscus exchange a glance.

DR. FRANCISCUS

Under the circumstances—

SCHUYLER

(interrupting)

Your father is resting now, dear.

Victoria goes stubbornly to the door and knocks on it. Schuyler takes a step toward her but too late. The doors have opened.

133. NEW ANGLE

shooting at Victoria from inside the salon. She comes ten feet into the room.

VICTORIA

Daddy! I just want to tell you I’ll do everything you said. Everything you had time to tell me on the boat. Everything, I’ll do, Daddy. Don’t ever worry.

(pp. 70-71)

Later after Van Greff dies and Wales believes he will not be able to regain custody of Victoria, two old friends of Wales turn up, somewhat drunk. Wales tells his daughter that they are parasites and that their annoying behavior results from loneliness, and another extremely sentimental section then ensues:

VICTORIA

What do they want?

WALES

Sometimes it’s your happiness.

VICTORIA

(looks around with interest)

How do they get to be that?

WALES

Oh, they begin by not doing their lessons.

VICTORIA (with a sigh)

I knew there’d be a moral in it.

(pause)

I wish there was some person who could talk to you without always ending up with a moral.

WALES

Darling, from now on, word of honor, that’ll be me.

They dance in silence a moment.

VICTORIA

I suppose this is the happiest that you can ever get, isn't it?

WALES

I suppose so. Just about.

VICTORIA

(sorry for everybody else)

I hope those parasites have found somebody to annoy, because they might as well be happy, too.

(P. 133)

Fitzgerald’s script was also technically flawed. It contained far too many scene climaxes, an effect, according to film critic Robert Gessner that “can lessen the impact of plot and character.” In his analysis of Cosmopolitan, Gessner found nine climaxes just in the last eleven pages, and, further, he noted that the majority were narrative ideas, not dramatized, and not one was especially cinematic[60].

Elsewhere, however, Fitzgerald’s script did contain a number of good visual effects. Especially striking is the section in which Helen Wales commits suicide:

82. CABIN OF A SHIP’S OFFICER.

The Doctor stands by the Ship’s Officer, bag in hand, with a worried expression. A Deck Steward in shot.

SHIP’S OFFICER

(to Deck Steward)

Cherchez par tout le bateau. Il faut trouvez [sic] Madame Wales.

(Look all over the boat. We must find Mrs. Wales.)

DECK STEWARD

Oui, mon lieutenant.

83. CHILDREN’S PLAYROOM.

Small children are on a see-saw. Older children are playing ball. Victoria stands nearby but has not joined in—she doesn’t feel gay.

84. A MONTAGE effect: CHARLES WALES’ FACE

very distraught, with other faces around him—all speaking to him.

VOICES

Not here, Mr. Wales.

Not there, Mr. Wales.

Not in her room.

Not in the bar, Mr. Wales.

Not in there, Mr. Wales.

Throughout this, the ship’s dance orchestra is playing tunes of 1929 in a nervous rhythm.

85. A DARK SKY FILLED WITH SEAGULLS.

The sudden sound a wild shriek—which breaks down after a moment, into the cry of the gulls as they swoop in a great flock down toward the water. Through their cries we hear the ship’s bell signalling for the engines to stop.

86. MEDIUM SHOT. STERN OF THE SHIP.

Ship receding from the camera as the awful sounds gradually die out.

FADE OUT.

(pp. 41-42)

Unfortunately, Fitzgerald was unable to maintain this level of writing throughout the script.

That producer Cowan assisted him greatly in the writing of Cosmopolitan is attested to by Fitzgerald’s notes and correspondence as well as his statement of appreciation at the end of the revised version of the script. There were, however, some disagreements between them. Fitzgerald, annoyed at an attempt to change the script, flailed out at what he called “this wretched star system.” He wrote, “The writing on the wall is that anybody this year who brings in a good new story intact will make more reputation and even money, than those who struggle for a few stars.”[61]

Fitzgerald had just seen Preston Sturges’ film comedy The Great McGinty, featuring such excellent actors as Brian Donlevy, Akim Tamiroff, and William Demarest, none, however, a top Hollywood star. Although he found the film to be “inferior in pace” and “an old story,” he called it a success because “it had not suffered from compromises, polish jobs, formulas and that familiarity which is so falsely consoling to producers.”[62] In addition, he was clearly impressed because Sturges had both written and directed the film. On September 14, 1940, Fitzgerald wrote his wife: “They’ve let a certain writer here direct his own pictures and he has made such a go of it that there may be a different feeling about that soon. If I had that chance, I would attain my real goal in coming here in the first place.”[63] But he would never have the opportunity.

Meanwhile, in August, he had been hired by Twentieth Century-Fox to help revise the script for the film Brooklyn Bridge, which dealt with the building of the bridge as well as the involvement of Boss Tweed. He disliked the script, calling it “formula stuff throughout,”[64] criticized the poor blending of the two plots, and suggested a complete rewriting, but the film was soon shelved. He then stayed on at Twentieth Century-Fox to work on a film adaptation of Emlyn Williams’ play, The Light of Heart. Again, after a few weeks, this project too was dropped. While retaining many of the original scenes and much of the original dialogue, Fitzgerald’s script did add a few scenes that were dramatically effective. In his opening scene he showed the hero, a former actor and now a department store Santa Claus, drunkenly distributing toys on the street despite an order that they were not to be given away:

We spot the delinquent one treading on the heels of the man ahead of him. The Santa Clauses spread in different directions, but our Santa Claus has gone through an ordeal, and in desperation he clutches an ash can and hangs there a second.

9 EXT. DOOR OF THE EMPLOYEES ENTRANCE—THE PERSONNEL MANAGER

staring o.s.

10 BY THE ASH CAN—OUR SANTA CLAUS

pulling himself together, walking off swiftly.

dissolve to:

11 SECTION OF A BUSY STREET—SLOWER ACTION

Our Santa Claus walking unsteadily. He comes to a small crowd, mostly children, gathered around someone unseen. He puts his hands on the back of a little boy and stands on tiptoes to see.

12 WHAT HE SEES--ANOTHER SANTA CLAUS

with an iron pot collecting for the Salvation Army.

13 CLOSE SHOT--OUR SANTA CLAUS

staring, fascinated. Absent-mindedly he takes out his handkerchief and starts to blow his nose—in doing so he feels his face and is astonished and shocked to find it inaccessible. On his panic

dissolve to:

14 A STREET—OUR SANTA CLAUS

walking slowly. His handkerchief is tangled in his beard—but that is not all. The strings by which the toys are slung have mysteriously become tangled about his arms. Impatiently he stops and breaks the cord of one. Three or four children are following him. He looks at the woolly lamb in his hand as if wondering how it got there. Then remembering the Personnel Manager’s admonition about the spirit of giving, he presents it to one of the little hoys. The little boy draws back.

BOY

I haven’t got a bob.

SANTA CLAUS

(dimly)

The Displays are not for sale.

Santa Claus moves along, snapping strings rapidly, and handing out toys…[65]

Near the end of the script, the actor, now making a comeback in King Lear, loses confidence in himself upon learning that his daughter is leaving him to get married and goes on a drinking spree. Frantically, the daughter and her friends search for him. The scene is as dramatic as the previous one. This time, however, because of an effective use of camera movement and editing, it is also cinematic:

268- A MONTAGE—COMPOSED OF THE FOLLOWING:

271 A.) SIGN OUTSIDE A LOW PUB—“THE BIRD-IN-HAND.”

B.) INT. “BIRD-IN-HAND”—CATHERINE, WALTERS, PUB-KEEPER.

PUB-KEEPER

—left here an hour ago.

C.) INT. ANOTHER PUB—CATHERINE, WALTERS AND PUB-KEEPER

PUB-KEEPER

’Avn’t seen him for a whole year.

'Ear ’e’s an actor now.

D.) ext. steps of the green room club—a third-rate theatrical club in a basement. A porter in a dirty uniform trying to keep Catherine out.

PORTER

’Ere! No ladies! I tell you Mr. Duncan’s been gone ten minutes.

Catherine is in despair. Without belief she speaks to Walters.

CATHERINE

He may be at the theatre

cut to:

272 LONG SHOT—SAVOY THEATRE

The queue for gallery seats now extends almost a block

273 MED. CLOSE SHOT—LADY MACHEN

in the queue—sitting on her shooting stick, her arms folded calmly. Comparatively she is near the head of the queue, about thirty people ahead of her. People in dress clothes pass. The queue moves up.

dissolve to:

274— INT. THEATRE----BY THE BACKSTAGE PHONE—GROUP SHOT

Robert is on the phone; anxiously listening are Mackay’s dresser, the make-up man, Sigane and Wopper, two or three actors, others.

ROBERT

(into phone)

Have the police any report of an accident?

275—LADY MACHEN--CAMERA HOLDS ON HER FOR A MOMENT AND THEN BEGINS TO TRUCK AT A MEDIUM PACE DOWN THE LONG LINE OF THE QUEUE AS IT MOVES UP SLOWLY LIKE A SNAKE

The people’s faces are expectant—most are of the educated classes, school teachers, civil servants, etc., many in threadbare overcoats; quite a few young college students. When the camera picks up the silhouette of one figure swaying drunkenly in line, it seems out of place. The man has failed to move up and there are protests.

A MAN

Move up, please.

A WOMAN

He’s intoxicated!

276— CLOSE SHOT—THE SAME BLEARY, CONFUSED FACE THAT WE SAW BEHIND THE SANTA CLAUS MASK--MACKAY DUNCAN--

mad as a hatter with drink, standing in his own queue.

277—ACROSS THE STREET--CATHERINE AND WALTERS

Catherine, frantic and helpless, looks offscene and sees Mackay.

CATHERINE

(in a strangled voice)

It’s him! It’s Tadda!

As she starts to run recklessly across the street, in front of the fashionable limousines headed for the theatre, the scene

FADES OUT

(pp. 120-122)

The Light of Heart was Fitzgerald’s final film job. During these last three years he had learned much about the movie colony as well as about film writing. He had worked for several of the major studios and had gained knowledge about the others. Like Nick Carraway, he too was both participant and observer. Throughout this period, he had been accumulating ideas for his next major work and was to devote much of the last year of his life to a fruitless attempt to complete his novel about Hollywood, The Last Tycoon.

Notes:

[1] Fitzgerald to Mrs. Richard Taylor, [Postmarked July 5, 1937], The Letters of F. Scott Fitzgerald, ed. Andrew Turnbull (New York: Scribners, 1963), p. 419. Hereafter cited as Letters.

[2] Fitzgerald to Frances Scott Fitzgerald, [July, 1937], Letters, p. 17.

[3] Ms. note, The Last Tycoon, The F. Scott Fitzgerald Papers, Princeton University Library, Princeton, New Jersey. Hereafter cited as Fitzgerald Papers.

[4] Fitzgerald to Mrs. Harold Ober, July 26, 1937, Letters, p. 553.

[5] Fitzgerald to Mrs. Bayard Turnbull, [fall, 1937], Letters, p. 443.

[6] Fitzgerald to Frances Scott Fitzgerald, [winter, 1939], Letters, p. 48.

[7] Fitzgerald to Zelda Fitzgerald, September 14, 1940, Letters, p. 124.

[8] The reader must realize the difficulties in determining the contribution of a writer to a script. Despite the fact that one or two writers may be given credit for the film, the script may have been the result of contributions from many writers as well as others involved in the project. Studios and writers’ guilds at times attempt to keep track of these contributions by requiring use of different colored copy, registration, etc., but even these means do not guarantee certain identification. Despite these obstacles, however, it is possible, based on the scripts and notes at the Princeton University Library, to make judgments about Fitzgerald’s Hollywood work.

[9] The Lion’s Share: The Story of an Entertainment Empire (New York: Dutton, 1957), P. 246.

[10] See Fitzgerald to Berg, Dozier, and Allen, February 23, 1940, Fitzgerald Papers.

[11] The quotation is from a note dated July 12, 1937, in folder “Yank at Oxford: Analysis, Treatment, and Dialogue by F. Scott Fitzgerald” in the Fitzgerald Papers. All quoted material from this film hereafter cited is in this folder.

[12] "Character of Molly,” July 22, 1937, p. 1.

[13] Ibid., p. 2.

[14] “Here is the scene as written . . . pp. 1-2; “Molly in the Train Scene,” p. 1.

[15] Three Comrades by F. Scott Fitzgerald, MGM script, September 1, 1937 (below this the date “10/6” is written in hand), pp. [1]-2, Fitzgerald Papers. Hereafter cited in the text.

[16] Ms. note, The Last Tycoon, Fitzgerald Papers.

[17] Erich Maria Remarque, Three Comrades, trans. A. W. Wheen (Boston: Little, Brown, 1937), pp. 172-173.

[18] The Great Gatsby (New York: Scribners, 1925, copyright, 1953), p. 87.

[19] The Last Tycoon: An Unfinished Novel, ed. Edmund Wilson (New York: Scribners, 1941), P. 31. Hereafter cited in the text.

[20] Jacques Bontemps and Richard Overstreet, “Measure for Measure: Interview with Joseph L. Mankiewicz,” Cahiers du Cinema in English, No. 8 (February, 1967), p. 31.

[21] See Fitzgerald to Mankiewicz, September 4, 1937, and Mankiewicz to Fitzgerald, September 9, 1937, Fitzgerald Papers.

[22] Fitzgerald to Paramore, October 24, 1937, Letters, p. 559.

[23] Paramore to Fitzgerald, January 25, 1938, Fitzgerald Papers.

[24] Three Comrades by F. Scott Fitzgerald and E. E. Paramore (“Script okayed by Joseph Mankiewicz”), MGM, February 1, 1938, Fitzgerald Papers. Hereafter cited in the text.

[25] Fitzgerald to Mankiewicz, January 17, 1938, Letters, p. 561.

[26] Fitzgerald to Mankiewicz, January 20, 1938, Letters, p. 563.

[27] Fitzgerald to Mankiewicz, January 17, 1938, Letters, p. 562.

[28] Fitzgerald to Mankiewicz, January 20, 1938, Letters, p. 563.

[29] Fitzgerald to Matthew Josephson, March 11, 1938, Letters, p. 572.

[30] New York Times, June 3, 1938, p. 12.

[31] The Film Till Now: A Survey of World Cinema, rev. cd. (I.ondon: Spring Books, 1967), p. 490.

[32] Fitzgerald to Mr. and Mrs. Eben Finney, March 16, 1938, Letters, p. 576.

[33] Fitzgerald to Maxwell Perkins, March 4, 1938, Letters, p. 276.

[34] “Infidelity,” part of the series “Grounds for Divorce,” appeared in Hearst's International-Cosmopolitan, CIV (February, 1938), 28-29ff. Fitzgerald worked from a treatment now in the Fitzgerald Papers similar to but not exactly the same as the short story.

[35] Memorandum from Hunt Stromberg, February 11, 1938, Fitzgerald Papers.

[36] These diagrams are in the Fitzgerald Papers.

[37] Fitzgerald to Stromberg, February 22, 1938, Fitzgerald Papers.

[38] Infidelity by F. Scott Fitzgerald, MGM script dated March 9, 1938 (below this date, the dates March “12” and “23” are written in hand), p. 74, Fitzgerald Papers. Hereafter cited in the text.

[39] Fitzgerald to Frances Scott Fitzgerald, [spring, 1938], Letters, p. 29.

[40] “Test Pilot,” Fitzgerald Papers.

[41] “Argument for Stromberg,’’ April 21, 1938, Fitzgerald Papers.

[42] The diagrams are in the Fitzgerald Papers.

[43] “New Treatment for End of: ‘Infidelity,’” May 10, 1938, p. 6, Fitzgerald Papers.

[44] Fitzgerald to Leland Hayward, December 6, 1939, Fitzgerald Papers.

[45] The Rest of the Story (New York: Coward-McCann, 1964), p. 16. The typescript is in the Fitzgerald Papers.

[46] Treatment of The Women, June 6, 1938, p. 11, Fitzgerald Papers.

[47] Fitzgerald to Frances Scott Fitzgerald, n.d., Letters, p. 102. Copies of Madame Curie “Second Revise” by Fitzgerald, January 3, 1939, and The Barretts of Wimpole Street by Ernest Vajda and Claudine West, MGM script dated March 20, 1934. are in the Fitzgerald Papers.

[48] Fitzgerald to Frances Scott Fitzgerald, [winter, 1939], Letters, p. 50. The film was released in 1943 with script by Paul Osborn and Paul H. Rameau.

[49] The two diagrams and a letter alluding to the plot, Fitzgerald to Edwin II. Knopf, October 26, 1938, are in the Fitzgerald Papers.

[50] See, e.g., Fitzgerald to Berg, Dozier, and Allen, February 23, 1940; Fitzgerald to Leland Hayward, December 6, 1939; and Fitzgerald’s script for the first half of Gone with the Wind; all in the Fitzgerald Papers.

[51] Fitzgerald to Frances Scott Fitzgerald, [winter, 1939], Letters, pp. 49-50.

[52] Fitzgerald to Perkins, February 25, 1939, Letters, p. 284.

[53] A treatment of Winter Carnival dated February 3, 1938 [1939], is on file in the Fitzgerald Papers. Schulberg’s 1950 novel, The Disenchanted, was based upon his relationship with Fitzgerald during this period.

[54] The Last Tycoon, p. 152.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Fitzgerald sequences for Air Raid, dated March 14 through 31, 1939, as well as earlier sequences by Donald Ogden Stewart; Fitzgerald’s treatment of Open that Door; and his notes for Raffles are in the Fitzgerald Papers. Also see Fitzgerald to Leland Hayward, December G, 1939, and Joseph I. Breen to Samuel Goldwyn, September 6, 1939, Fitzgerald Papers.

[57] See Fitzgerald’s copy of Everything Happens at Night by Art Arthur and Robert Harari, March 8, 1939; Fitzgerald to Harry Joe Brown. October 31, 1939; and Fitzgerald to Berg, Dozier, and Allen, February 23, 1940; Fitzgerald Papers.

[58] Two distinct versions of Cosmopolitan, one dated July 30, 1940, and a second draft revised dated August 13, 1940, are in the Fitzgerald Papers. All references are to the second draft revised and are cited in the text. Also see Sheilah Graham, College of One (New York: Viking, 1967), p. 138; Fitzgerald to Zelda Fitzgerald, September 14, 1940, Letters, p. 123; and Fitzgerald to Cowan, September 28, 1940, and Fitzgerald to Cowan, dated Monday night, Fitzgerald Papers.

[59] Tender Is the Night (New York: Scribners, 1934, rpt. ed.), p. 69.

[60] The Moving Image: A Guide to Cinematic Literacy (New York: Dutton, 1968), p. 248.

[61] Fitzgerald to Lester Cowan, dated Monday night, Fitzgerald Papers.

[62] Ibid.

[63] Fitzgerald to Zelda Fitzgerald, September 14, 1940, Letters, p. 124. It is not certain that Fitzgerald was referring to Sturges, but the proximity of dates suggests this.

[64] “An Opinion on ‘Brooklyn Bridge,'” August 12, 1940, Fitzgerald Papers.

[65] The Light of Heart, first draft continuity, dated October 11, 1940, pp. 3-4. Fitzgerald Papers. Hereafter cited in the text. While it is possible that this section may have been written by another writer and retained by Fitzgerald, his copy of the playscript with its penciled notations and Sheilah Graham’s comments (College of One, p. 135) suggest that he wrote this scene as well as the next quoted. The film eventually was produced in 1942 as Life Begins at Eight-Thirty with screenplay by Nunnally Johnson.

Published in The Princeton University Library Chronicle magazine (Volume XXXII, Winter 1971, Number 2).