Sleeping and waking

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

When some years ago I read a piece by Ernest Hemingway called Now I Lay Me, I thought there was nothing further to be said about insomnia. I see now that that was because I had never had much; it appears that every man’s insomnia is as different from his neighbor’s as are their daytime hopes and aspirations.

Now if insomnia is going to be one of your naturals, it begins to appear in the late thirties. Those seven precious hours of sleep suddenly break in two. There is, if one is lucky, the “first sweet sleep of night” and the last deep sleep of morning, but between the two appears a sinister, ever widening interval. This is the time of which it is written in the Psalms: Scuto circumdabit te veritas eius: non timebis a timore nocturno, a sagitta volante in die, a negotio perambulante in tenebris.

With a man I knew the trouble commenced with a mouse; in my case I like to trace it to a single mosquito.

My friend was in course of opening up his country house unassisted, and after a fatiguing day discovered that the only practical bed was a child’s affair—long enough but scarcely wider than a crib. Into this he flopped and was presently deeply engrossed in rest but with one arm irrepressibly extending over the side of the crib. Hours later he was awakened by what seemed to be a pin-prick in his finger. He shifted his arm sleepily and dozed off again—to be again awakened by the same feeling.

This time he flipped on the bed-light—and there attached to the bleeding end of his finger was a small and avid mouse. My friend, to use his own words, “uttered an exclamation,” but probably he gave a wild scream.

The mouse let go. It had been about the business of devouring the man as thoroughly as if his sleep were permanent. From then on it threatened to be not even temporary. The victim sat shivering, and very, very tired. He considered how he would have a cage made to fit over the bed and sleep under it the rest of his life. But it was too late to have the cage made that night and finally he dozed, to wake in intermittent horrors from dreams of being a Pied Piper whose rats turned about and pursued him.

He has never since been able to sleep without a dog or cat in the room.

My own experience with night pests was at a time of utter exhaustion—too much work undertaken, interlocking circumstances that made the work twice as arduous, illness within and around—the old story of troubles never coming singly. And ah, how I had planned that sleep that was to crown the end of the struggle—how I had looked forward to the relaxation into a bed soft as a cloud and permanent as a grave. An invitation to dine a deux with Greta Garbo would have left me indifferent.

But had there been such an invitation I would have done well to accept it, for instead I dined alone, or rather was dined upon by one solitary mosquito.

It is astonishing how much worse one mosquito can be than a swarm. A swarm can be prepared against, but one mosquito takes on a personality—a hatefulness, a sinister quality of the struggle to the death. This personality appeared all by himself in September on the twentieth floor of a New York hotel, as out of place as an armadillo. He was the result of New Jersey’s decreased appropriation for swamp drainage, which had sent him and other younger sons into neighboring states for food.

The night was warm—but after the first encounter, the vague slappings of the air, the futile searches, the punishment of my own ears a split second too late, I followed the ancient formula and drew the sheet over my head.

And so there continued the old story, the bitings through the sheet, the sniping of exposed sections of hand holding the sheet in place, the pulling up of the blanket with ensuing suffocation—followed by the psychological change of attitude, increasing wakefulness, wild impotent anger—finally a second hunt.

This inaugurated the maniacal phase—the crawl under the bed with the standing lamp for torch, the tour of the room with final detection of the insect’s retreat on the ceiling and attack with knotted towels, the wounding of oneself—my God!

—After that there was a short convalescence that my opponent seemed aware of, for he perched insolently beside my head—but I missed again.

At last, after another half hour that whipped the nerves into a frantic state of alertness came the Pyrrhic victory, and the small mangled spot of blood, my blood, on the headboard of the bed.

As I said, I think of that night, two years ago, as the beginning of my sleeplessness—because it gave me the sense of how sleep can be spoiled by one infinitesimal incalculable element. It made me, in the now archaic phraseology, “sleep-conscious.” I worried whether or not it was going to be allowed me. I was drinking, intermittently but generously, and on the nights when I took no liquor the problem of whether or not sleep was specified began to haunt me long before bedtime.

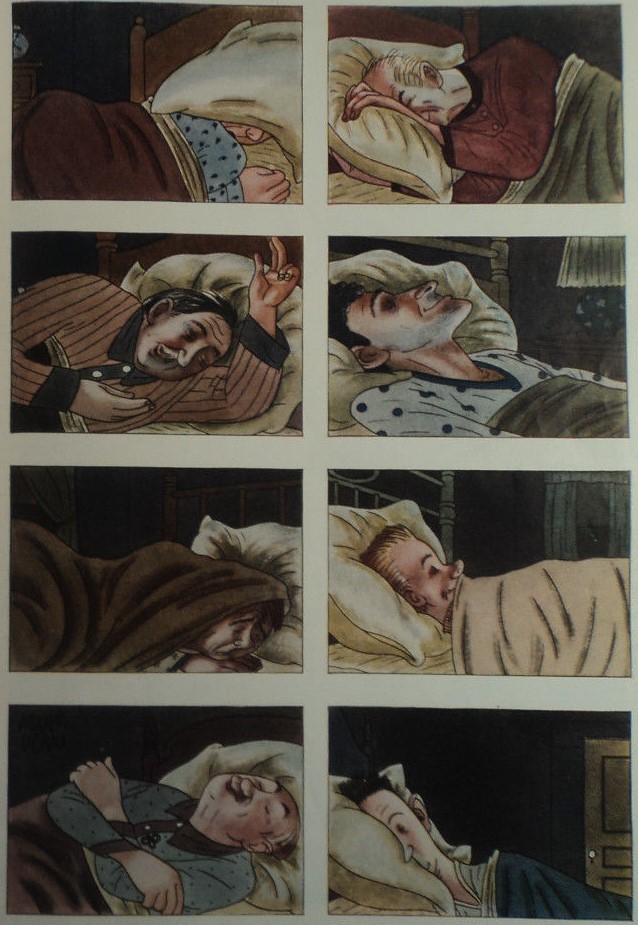

A typical night (and I wish I could say such nights were all in the past) comes after a particularly sedentary work-and-cigarette day. It ends, say without any relaxing interval, at the time for going to bed. All is prepared, the books, the glass of water, the extra pajamas lest I awake in rivulets of sweat, the luminol pills in the little round tube, the note book and pencil in case of a night thought worth recording. (Few have been—they generally seem thin in the morning, which does not diminish their force and urgency at night.)

I turn in, perhaps with a night-cap—I am doing some comparatively scholarly reading for a coincident work so I choose a lighter volume on the subject and read till drowsy on a last cigarette. At the yawning point I snap the book on a marker, the cigarette at the hearth, the button on the lamp. I turn first on the left side, for that, so I’ve heard, slows the heart, and then—coma.

So far so good. From midnight until two-thirty peace in the room. Then suddenly I am awake, harassed by one of the ills or functions of the body, a too vivid dream, a change in the weather for warm or cold.

The adjustment is made quickly, with the vain hope that the continuity of sleep can be preserved, but no—so with a sigh I flip on the light, take a minute pill of luminol and reopen my book. The real night, the darkest hour, has begun. I am too tired to read unless I get myself a drink and hence feel bad next day—so I get up and walk. I walk from my bedroom through the hall to my study, and then back again, and if it’s summer out to my back porch. There is a mist over Baltimore; I cannot count a single steeple. Once more to the study, where my eye is caught by a pile of unfinished business: letters, proofs, notes, etc. I start toward it, but No! this would be fatal. Now the luminol is having some slight effect, so I try bed again, this time half circling the pillow on edge about my neck.

“Once upon a time” (I tell myself) “they needed a quarterback at Princeton, and they had nobody and were in despair. The head coach noticed me kicking and passing on the side of the field, and he cried: ‘Who is that man—why haven’t we noticed him before?’ The under coach answered, ‘He hasn’t been out,’ and the response was: ‘Bring him to me.’”

“…we go to the day of the Yale game. I weigh only one hundred and thirty-five, so they save me until the third quarter, with the score—”

—But it’s no use—I have used that dream of a defeated dream to induce sleep for almost twenty years, but it has worn thin at last. I can no longer count on it—though even now on easier nights it has a certain lull…

The war dream then: the Japanese are everywhere victorious—my division is cut to rags and stands on the defensive in a part of Minnesota where I know every bit of the ground. The headquarters staff and the regimental battalion commanders who were in conference with them at the time have been killed by one shell. The command devolved upon Captain Fitzgerald. With superb presence…

—but enough; this also is worn thin with years of usage. The character who bears my name has become blurred. In the dead of the night I am only one of the dark millions riding forward in black buses toward the unknown.

Back again now to the rear porch, and conditioned by intense fatigue of mind and perverse alertness of the nervous system—like a broken-stringed bow upon a throbbing fiddle—I see the real horror develop over the roof-tops, and in the strident horns of night-owl taxis and the shrill monody of revelers’ arrival over the way. Horror and waste—

—Waste and horror—what I might have been and done that is lost, spent, gone, dissipated, unrecapturable. I could have acted thus, refrained from this, been bold where I was timid, cautious where I was rash.

I need not have hurt her like that.

Nor said this to him.

Nor broken myself trying to break what was unbreakable.

The horror has come now like a storm—what if this night prefigured the night after death—what if all thereafter was an eternal quivering on the edge of an abyss, with everything base and vicious in oneself urging one forward and the baseness and viciousness of the world just ahead. No choice, no road, no hope—only the endless repetition of the sordid and the semi-tragic. Or to stand forever, perhaps, on the threshold of life unable to pass it and return to it. I am a ghost now as the clock strikes four.

On the side of the bed I put my head in my hands. Then silence, silence—and suddenly—or so it seems in retrospect—suddenly I am asleep.

Sleep—real sleep, the dear, the cherished one, the lullaby. So deep and warm the bed and the pillow enfolding me, letting me sink into peace, nothingness—my dreams now, after the catharsis of the dark hours, are of young and lovely people doing young, lovely things, the girls I knew once, with big brown eyes, real yellow hair.

In the fall of ’16 in the cool of the afternoon

I met Caroline under a white moon

There was an orchestra—Bingo-Bango

Playing for us to dance the tango

And the people all clapped as we arose

For her sweet face and my new clothes -

Life was like that, after all; my spirit soars in the moment of its oblivion; then down, down deep into the pillow…

“…Yes, Essie, yes.—Oh, My God, all right, I’ll take the call myself.”

Irresistible, iridescent—here is Aurora—here is another day.

Note

See the full version of the poem included in this essay, in The Notebooks, J, entry 857.

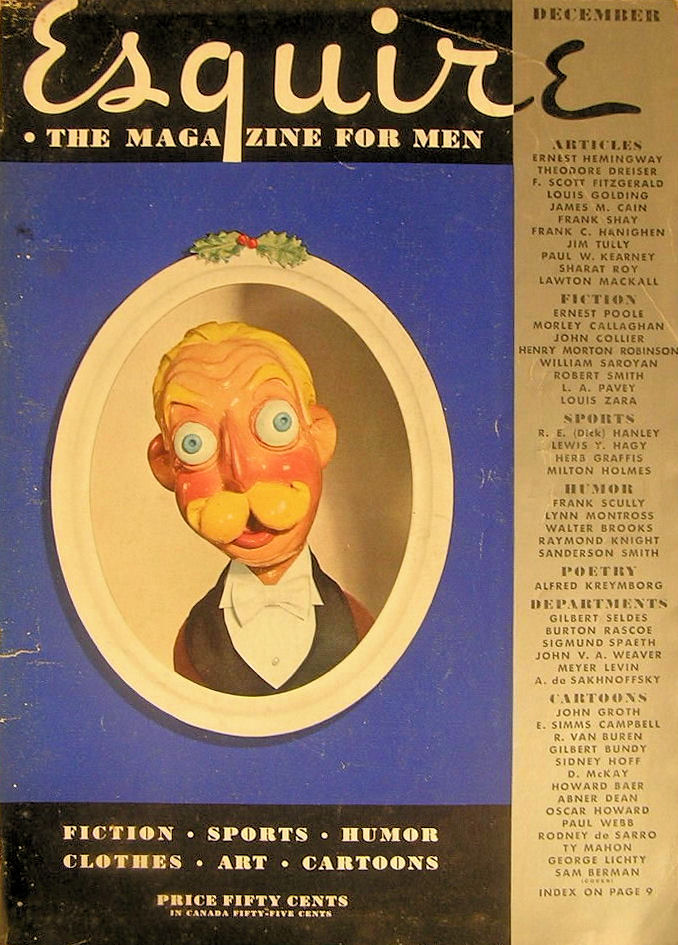

Published in Esquire magazine (December 1934).

Illustrations by (unknown Esquire artist).