One Hundred False Starts

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

“Crack!” goes the pistol and off starts this entry. Sometimes he has caught it just right; more often he has jumped the gun. On these occasions, if he is lucky, he runs only a dozen yards, looks around and jogs sheepishly back to the starting place. But too frequently he makes the entire circuit of the track under the impression that he is leading the field, and reaches the finish to find he has no following. The race must be run all over again.

A little more training, take a long walk, cut out that nightcap, no meat at dinner, and stop worrying about politics—

So runs an interview with one of the champion false starters of the writing profession—myself. Opening a leather-bound waiste-basket which I fatuously refer to as my “notebook,” I pick out at random a small, triangular piece of wrapping paper with a canceled stamp on one side. On the other side is written:

Boopsie Dee was cute.

Nothing more. No cue as to what was intended to follow that preposterous statement. Boopsie Dee, indeed, confronting me with this single dogmatic fact about herself. Never will I know what happened to her, where and when she picked up her revolting name, and whether her cuteness got her into much trouble.

I pick out another scrap:

Article: Unattractive Things Girls Do, to pair with counter article by woman: Unattractive Things Men Do.

No. 1. Remove glass eye at dinner table.

That’s all there is on that scrap. Evidently, an idea that had dissolved into hilarity before it had fairly got under way. I try to revive it seriously. What unattractive things do girls do—I mean universally nowadays—or what unattractive things do a great majority of them do, or a strong minority? I have a few feeble ideas, but no, the notion is dead. I can only think of an article I read somewhere about a woman who divorced her husband because of the way he stalked a chop, and wondering at the time why she didn’t try him out on a chop before she married him. No, that all belongs to a gilded age when people could afford to have nervous breakdowns because of the squeak in daddy’s shoes.

Lines to an Old Favorite

There are hundreds of these hunches. Not all of them have to do with literature. Some are hunches about importing a troupe of Ouled Nail dancers from Africa, about bringing the Grand-Guignol from Paris to New York, about resuscitating football at Princeton—I have two scoring plays that will make a coach’s reputation in one season—and there is a faded note to “explain to D.W. Griffith why costume plays are sure to come back.” Also my plan for a film version of H. G. Wells’ History of the World.

These little flurries caused me no travail—they were opium eater’s illusions, vanishing with the smoke of the pipe, or you know what I mean. The pleasure of thinking about them was the exact equivalent of having accomplished them. It is the six-page, ten-page, thirty-page globs of paper that grieve me professionally, like unsuccessful oil shafts; they represent my false starts.

There is, for example, one false start which I have made at least a dozen times. It is—or rather has tried to take shape as—a short story. At one time or another, I have written as many words on it as would make a presentable novel, yet the present version is only about twenty-five hundred words long and hasn’t been touched for two years. Its present name—it has gone under various aliases—is The Barnaby Family.

From childhood I have had a daydream—what a word for one whose entire life is spent noting them down—about starting at scratch on a desert island and building a comparatively high state of civilization out of the materials at hand. I always felt that Robinson Crusoe cheated when he rescued the tools from the wreck, and this applies equally to the Swiss Family Robinson, the Two Little Savages, and the balloon castaways of The Mysterious Island. In my story, not only would no convenient grain of wheat, repeating rifle, 4000 H. P. Diesel engine or technocratic butler be washed ashore but even my characters would he helpless city dwellers with no more wood lore than a cuckoo out of a clock.

The creation of such characters was easy, and it was easy washing them ashore:

For three long hours they were prostrated on the beach. Then Donald sat up.

“Well, here we are,” he said with sleepy vagueness.

“Where?” his wife demanded eagerly.

“It couldn’t be America and it couldn’t be the Philippines,” he said, “because we started from one and haven’t got to the other.”

“I’m thirsty,” said the child.

Donald’s eyes went quickly to the shore.

“Where’s the raft?” He looked rather accusingly at Vivian. “Where’s the raft?”

“It was gone when I woke up.”

“It would be,” he exclaimed bitterly. “Somebody might have thought of bringing the jug of water ashore. If I don’t do it, nothing is done in this house—I mean this family.”

All right, go on from there. Anybody—you back there in the tenth row—step up! Don’t be afraid. Just go on with the story. If you get stuck, you can look up tropical fauna and flora in the encyclopedia or call up a neighbor who has been shipwrecked.

Anyhow, that’s the exact point where my story—and I still think it’s a great plot—begins to creak and groan with unreality. I turn around after a while with a sense of uneasiness—how could anybody believe that rubbish about monkeys throwing coconuts?—trot back to the starting place, and I resume my crouch for days and days.

A Murder That Didn’t Jell

During such days I sometimes examine a clot of pages which is headed Ideas for Possible Stories. Among others, I find the following:

Bath water in Princeton or Florida.

Plot—suicide, indulgence, hate, liver and circumstance.

Snubbing or having somebody.

Dancer who found she could fly.

Oddly enough, all these are intelligible, if not enlightening, suggestions to me. But they are all old—old. I am as apt to be stimulated by them as by my signature or the beat of my feet pacing the floor. There is one that for years has puzzled me, that is as great a mystery as Boopsie Dee.

Story: THE WINTER WAS COLD

CHARACTERS

Victoria Cuomo

Mark de Vinci

Jason Tenweather

Ambulance surgeon

Stark, a watchman

What was this about? Who were these people? I have no doubt that one of them was to be murdered or else be a murderer. But all else about the plot I have forgotten long ago.

I turn over a little. Here is something over which I linger longer; a false start that wasn’t bad, that might have been run out.

Words

When you consider the more expensive article and finally decide on the cheaper one, the salesman is usually thoughtful enough to make it alt right for you. “You’ll probably get the most wear out of this,” he says consolingly, or even, “That’s the one I’d choose myself.”

The Trimbles were like that. They were specialists in the neat promotion of the next best into the best.

“It’ll do to wear around the house,” they used to say; or, “We want to wait until we can get a really nice one.”

It was at this point that I decided I couldn’t write about the Trimbles. They were very nice and I would have enjoyed somebody else’s story of how they made out, but I couldn’t get under the surface of their lives—what kept them content to make the best of things instead of changing things. So I gave them up.

There is the question of dog stories. I like dogs and would like to write at least one dog story in the style of Mr. Terhune, but see what happens when I take pen in hand:

DOG

THE STORY OF A LITTLE DOG

Only a newsboy with a wizened face, selling his papers on the corner. A big dog fancier, standing on the curb, laughed contemptuously and twitched up the collar of his Airedale coat. Another rich dog man gave a little bark of scorn from a passing taxicab.

But the newsboy was interested in the animal that had crept close to his feet. He was only a cur; his fuzzy coat was inherited from his mother, who had been a fashionable poodle, while in stature he resembled his father, a Great Dane. And somewhere there was a canary concerned, for a spray of yellow feathers projected from his backbone—

You see, I couldn’t go on like that. Think of dog owners writing in to the editors from all over the country, protesting that I was no man for that job.

I am thirty-six years old. For eighteen years, save for a short space during the war, writing has been my chief interest in life, and I am in every sense a professional.

Yet even now when, at the recurrent cry of “Baby needs shoes,” I sit down facing my sharpened pencils and block of legal-sized paper, I have a feeling of utter helplessness. I may write my story in three days or, as is more frequently the case, it may be six weeks before I have assembled anything worthy to be sent out. I can open a volume from a criminal-law library and find a thousand plots. I can go into highway and byway, parlor and kitchen, and listen to personal revelations that, at the hands of other writers, might endure forever. But all that is nothing—not even enough for a false start.

Twice-Told Tales

Mostly, we authors must repeat ourselves—that’s the truth. We have two or three great and moving experiences in our lives—experiences so great and moving that it doesn’t seem at the time that anyone else has been so caught up and pounded and dazzled and astonished and beaten and broken and rescued and illuminated and rewarded and humbled in just that way ever before.

Then we learn our trade, well or less well, and we tell our two or three stories—each time in a new disguise—maybe ten times, maybe a hundred, as long as people will listen.

If this were otherwise, one would have to confess to having no individuality at all. And each time I honestly believe that, because I have found a new background and a novel twist, I have really got away from the two or three fundamental tales I have to tell. But it is rather like Ed Wynn’s famous anecdote about the painter of boats who was begged to paint some ancestors for a client. The bargain was arranged, but with the painter’s final warning that the ancestors would all turn out to look like boats.

When I face the fact that all my stories are going to have a certain family resemblance, I am taking a step toward avoiding false starts. If a friend says he’s got a story for me and launches into a tale of being robbed by Brazilian pirates in a swaying straw hut on the edge of a smoking volcano in the Andes, with his fiancee bound and gagged on the roof, I can well believe there were various human emotions involved; but having successfully avoided pirates, volcanoes and fiancees who get themselves bound and gagged on roofs, I can’t feel them. Whether it’s something that happened twenty years ago or only yesterday, I must start out with an emotion—one that’s close to me and that I can understand.

It’s an Ill Wind

Last summer I was hauled to the hospital with high fever and a tentative diagnosis of typhoid. My affairs were in no better shape than yours are, reader. There was a story I should have written to pay my current debts, and I was haunted by the fact that I hadn’t made a will. If I had really had typhoid I wouldn’t have worried about such things, nor made that scene at the hospital when the nurses tried to plump me into an ice bath. I didn’t have either the typhoid or the bath, but I continued to rail against my luck that just at this crucial moment I should have to waste two weeks in bed, answering the baby talk of nurses and getting nothing done at all. But three days after I was discharged I had finished a story about a hospital.

The material was soaking in and I didn’t know it. I was profoundly moved by fear, apprehension, worry, impatience; every sense was acute, and that is the best way of accumulating material for a story. Unfortunately, it does not always come so easily. I say to myself—looking at the awful blank block of paper—“Now, here’s this man Swankins that I’ve known and liked for ten years. I am privy to all his private affairs, and some of them are wows. I’ve threatened to write about him, and he says to go ahead and do my worst.”

But can I? I’ve been in as many jams as Swankins, but I didn’t look at them the same way, nor would it ever have occurred to me to extricate myself from the Chinese police or from the clutches of that woman in the way Swankins chose. I could write some fine paragraphs about Swankins, but build a story around him that would have an ounce of feeling in it—impossible.

Or into my distraught imagination wanders a girl named Elsie about whom I was almost suicidal for a month, in 1916.

“How about me?” Elsie says. “Surely you swore to a lot of emotion back there in the past. Have you forgotten?”

“No, Elsie, I haven’t forgotten.”

“Well, then, write a story about me. You haven’t seen me for twelve years, so you don’t know how fat I am now and how boring I often seem to my husband.”

“No, Elsie, I—”

“Oh, come on. Surely I must be worth a story. Why, you used to hang around saying good-bye with your face so miserable and comic that I thought I’d go crazy myself before I got rid of you. And now you’re afraid even to start a story about me. Your feeling must have been pretty thin if you can’t revive it for a few hours.”

“No, Elsie; you don’t understand. I have written about you a dozen times. That funny little rabbit curl to your lip, I used it in a story six years ago. The way your face all changed just when you were going to laugh—I gave that characteristic to one of the first girls I ever wrote about. The way I stayed around trying to say good night, knowing that you’d rush to the phone as soon as the front door closed behind me—all that was in a book that I wrote once upon a time.”

“I see. Just because I didn’t respond to you, you broke me into bits and used me up piecemeal.”

“I’m afraid so, Elsie. You see, you never so much as kissed me, except that once with a kind of a shove at the same time, so there really isn’t any story.”

Plots without emotions, emotions without plots. So it goes sometimes. Let me suppose, however, that I have got under way; two days’ work, two thousand words are finished and being typed for a first revision. And suddenly doubts overtake me.

A Jury of One

What if I’m just horsing around? What’s going on in this regatta anyhow ? Who could care what happens to the girl, when the sawdust is obviously leaking out of her moment by moment? How did I get the plot all tangled up ? I am alone in the privacy of my faded blue room with my sick cat, the bare February branches waving at the window, an ironic paper weight that says Business is Good, a New England conscience—developed in Minnesota—and my greatest problem:

“Shall I run it out? Or shall I turn back?”

Shall I say:

“I know I had something to prove, and it may develop farther along in the story?”

Or:

“This is just bullheadedness. Better throw it away and start over.”

The latter is one of the most difficult decisions that an author must make. To make it philosophically, before he has exhausted himself in a hundred-hour effort to resuscitate a corpse or disentangle innumerable wet snarls, is a test of whether or not he is really a professional. There are often occasions when such a decision is doubly difficult. In the last stages of a novel, for instance, where there is no question of junking the whole, but when an entire favorite character has to be hauled out by the heels, screeching, and dragging half a dozen good scenes with him.

It is here that these confessions tie up with a general problem as well as with those peculiar to a writer. The decision as to when to quit, as to when one is merely floundering around and causing other people trouble, has to be made frequently in a lifetime. In youth we are taught the rather simple rule never to quit, because we are presumably following programs made by people wiser than ourselves. My own conclusion is that when one has embarked on a course that grows increasingly doubtful and feels the vital forces beginning to be used up, it is best to ask advice, if decent advice is within range. Columbus didn’t and Lindbergh couldn’t. So my statement at first seems heretical toward the idea that it is pleasantest to live with—the idea of heroism. But I make a sharp division between one’s professional life, when, after the period of apprenticeship, not more than 10 per cent of advice is worth a hoot, and one’s private and worldly life, when often almost anyone’s judgment is better than one’s own.

Once, not so long ago, when my work was hampered by so many—false starts that I thought the game was up at last, and when my personal life was even more thoroughly obfuscated, I asked an old Alabama Negro:

“Uncle Bob, when things get so bad that there isn’t any way out, what do you do then?”

Homely Advice, But Sound

The heat from the kitchen stove stirred his white sideburns as he warmed himself. If I cynically expected a platitudinous answer, a reflection of something remembered from Uncle Remus, I was disappointed.

“Mr. Fitzgerald,” he said, “when things get that—away I wuks.”

It was good advice. Work is almost everything. But it would be nice to be able to distinguish useful work from mere labor expended. Perhaps that is part of work itself—to find the difference. Perhaps my frequent, solitary sprints around the track are profitable. Shall I tell you about another one? Very well. You see, I had this hunch— But in counting the pages, I find that my time is up and I must put my book of mistakes away. On the fire? No! I put it weakly back in the drawer. These old mistakes are now only toys—and expensive ones at that—give them a toy’s cupboard and then hurry back into the serious business of my profession. Joseph Conrad defined it more clearly, more vividly than any man of our time:

“My task is by the power of the written word to make you hear, to make you feel—it is, before all, to make you see.”

It’s not very difficult to run back and start over again—especially in private. What you aim at is to get in a good race or two when the crowd is in the stand.

Editorial

This essay makes Fitzgerald’s life—or any author’s—sound easier and pleasanter than it was, though the evidence of how hard it was is here, if you look in such things as “I am alone in the privacy of my faded blue room with my sick cat, the bare February branches waving at the window, an ironic paper weight that says Business is Good, a New England conscience—developed in Minnesota—and my greatest problem.” That is a very exact description of Fitzgerald in his study at La Paix in the dark thirties, when he headed a letter to Edmund Wilson “La Paix (My God!).”

The writer of this essay is the Fitzgerald who no longer could feel that life might be a thing of sustained joy. He was beginning to tell himself, a he does here, that he must be a tough professional, an attitude toward his work which he never in fact succeeded in establishing completely, though he was going to insist on it more and more, until the insistence reached a climax in “Pasting It Together.” But the very irony with which “Afternoon of an Author” reasserts this idea shows the extent to which, even at the end, he had failed to commit himself to it completely. Because he was a writer who had to “start with an emotion—one that’s close to me and that I can understand,” personal emotional involvement in the experience he wrote about was as important to his work as was his objectivity. The deceptive simplicity with which this essay involves us in his personal struggles as a writer is a modest illustration of what that involvement meant for his work.

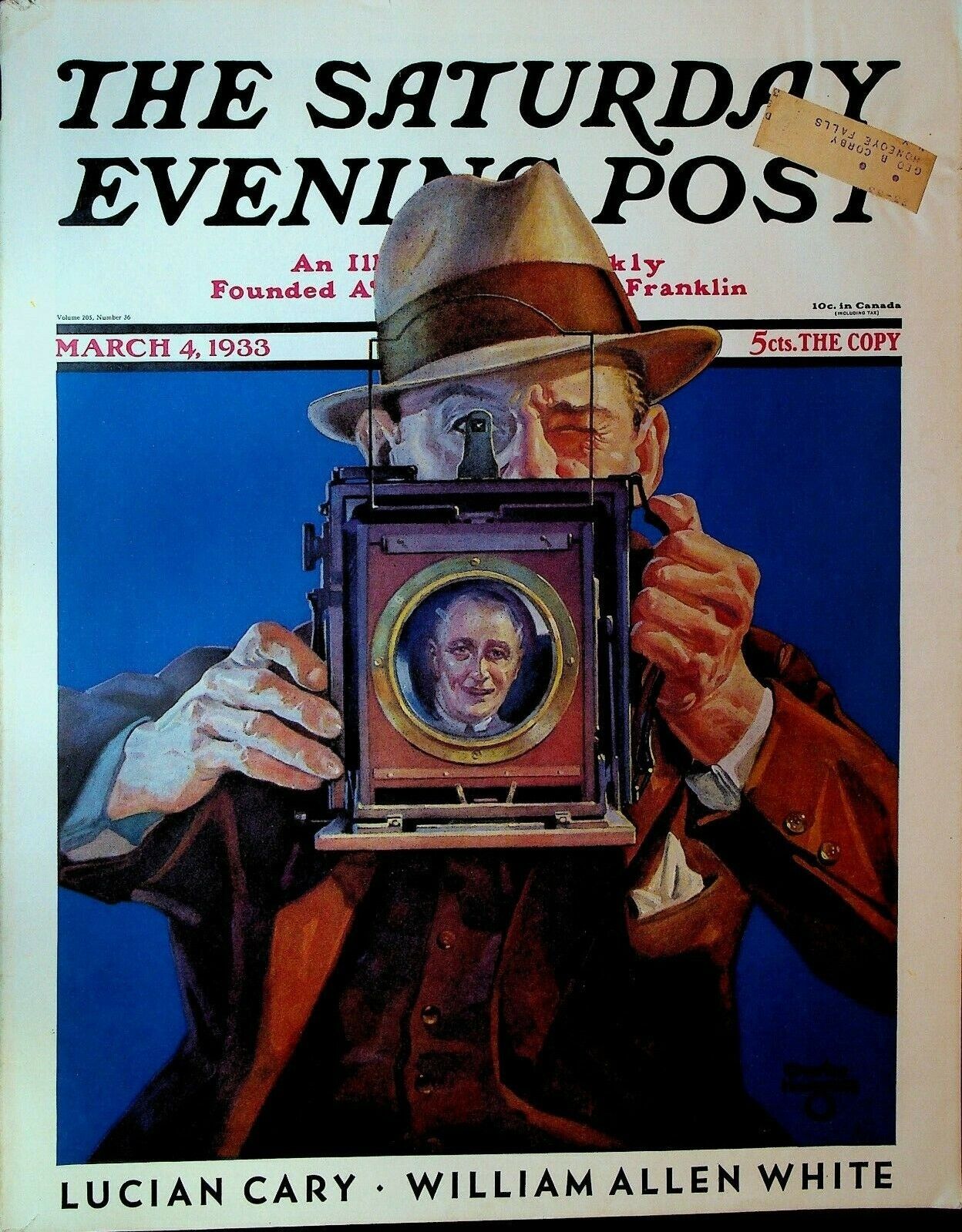

Published in The Saturday Evening Post magazine (March 4, 1933).

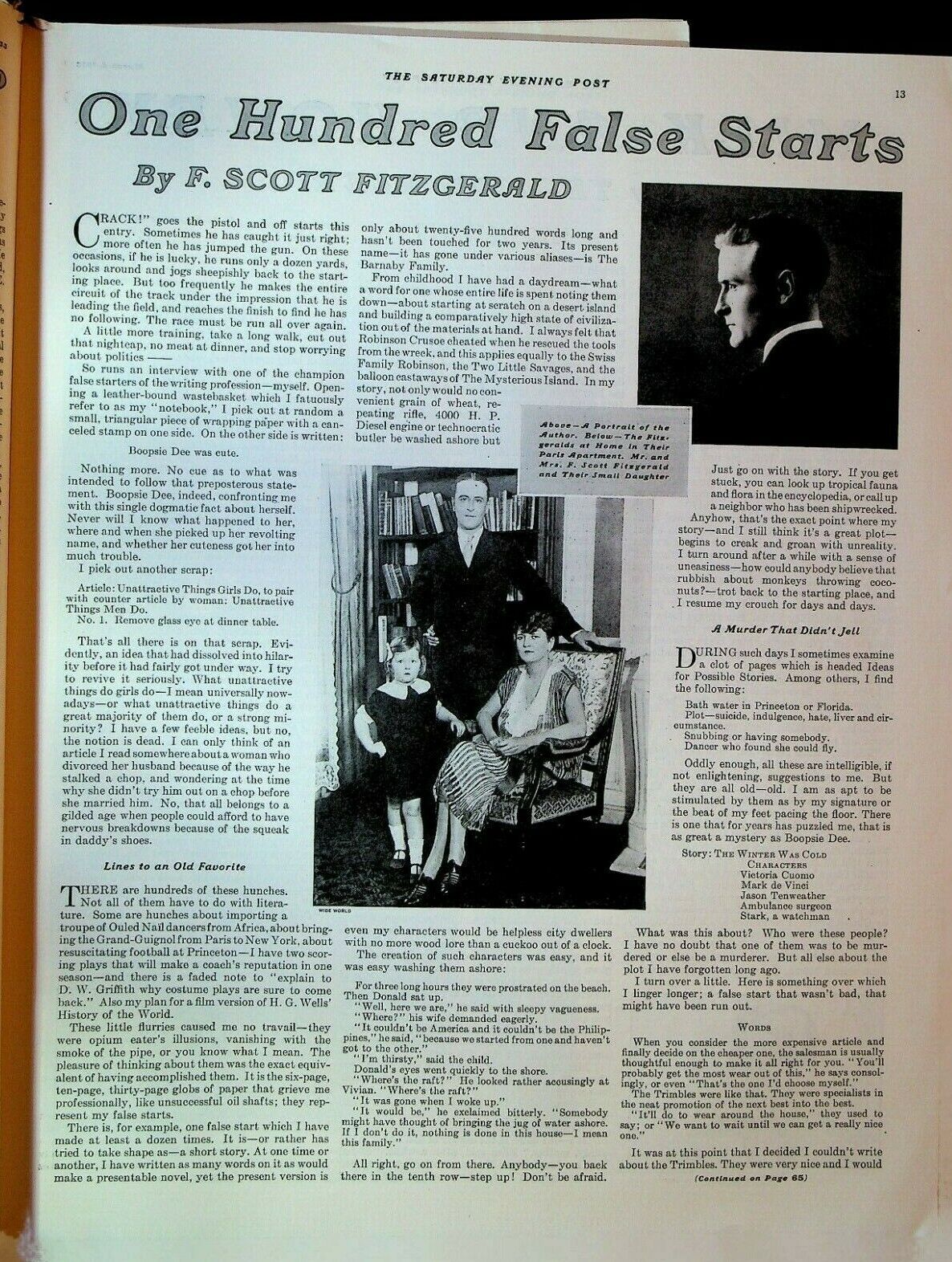

Illustrations by photographs.