How to Live on $36,000 a Year

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

“You ought to start saving money,” The Young Man With a Future assured me just the other day. “You think it’s smart to live up to your income. Some day you’ll land in the poorhouse.”

I was bored, but I knew he was going to tell me anyhow, so I asked him what I’d better do.

“It’s very simple,” he answered impatiently; “only you establish a trust fund where you can’t get your money if you try.”

I had heard this before. It is System Number 999. I tried System Number 1 at the very beginning of my literary career four years ago. A month before I was married I went to a broker and asked his advice about investing some money.

“It’s only a thousand,” I admitted, “but I feel I ought to begin to save right now.”

He considered.

“You don’t want Liberty Bonds,” he said. “They’re too easy to turn into cash. You want a good, sound, conservative investment, but also you want it where you can’t get at it every five minutes.”

He finally selected a bond for me that paid 7 per cent and wasn’t listed on the market I turned over my thousand dollars, and my career of amassing capital began that day.

On that day, also, it ended.

The Heirloom No One Would Buy

My wife and I were married in New York in the spring of 1920, when prices were higher than they had been within the memory of man. In the light of after events it seems fitting that our career should have started at that precise point in time. I had just received a large check from the movies and I felt a little patronizing toward the millionaires riding down Fifth Avenue in their limousines—because my income had a way of doubling every month. This was actually the case. It had done so for several months—I had made only thirty-five dollars the previous August, while here in April I was making three thousand—and it seemed as if it was going to do so forever. At the end of the year it must reach half a million. Of course with such a state of affairs, economy seemed a waste of time. So we went to live at the most expensive hotel in New York, intending to wait there until enough money accumulated for a trip abroad.

To make a long story short, after we had been married for three months I found one day to my horror that I didn’t have a dollar in the world, and the weekly hotel bill for two hundred dollars would be due next day.

I remember the mixed feelings with which I issued from the bank on hearing the news.

“What’s the matter?” demanded my wife anxiously, as I joined her on the sidewalk. “You look depressed.”

“I’m not depressed,” I answered cheerfully; “I’m just surprised. We haven’t got any money.”

“Haven’t got any money,” she repeated calmly, and we began to walk up the Avenue in a sort of trance. “Well, let’s go to the movies,” she suggested jovially.

It all seemed so tranquil that I was not a bit cast down. The cashier had not even scowled at me. I had walked in and said to him, “How much money have I got?” And he had looked in a big book and answered, “None.”

That was all. There were no harsh words, no blows. And I knew that there was nothing to worry about. I was now a successful author, and when successful authors ran out of money all they had to do was to sign checks. I wasn’t poor—they couldn’t fool me. Poverty meant being depressed and living in a small remote room and eating at a rotisserie on the corner, while I—why, it was impossible that I should be poor! I was living at the best hotel in New York!

My first step was to try to sell my only possession—my $1000 bond. It was the first of many times I made the attempt; in all financial crises I dig it out and with it go hopefully to the bank, supposing that, as it never fails to pay the proper interest, it has at last assumed a tangible value. But as I have never been able to sell it, it has gradually acquired the sacredness of a family heirloom. It is always referred to by my wife as “your bond,” and it was once turned in at the Subway offices after I left it by accident on a car seat!

This particular crisis passed next morning when the discovery that publishers sometimes advance royalties sent me hurriedly to mine. So the only lesson I learned from it was that my money usually turns up somewhere in time of need, and that at the worst you can always borrow—a lesson that would make Benjamin Franklin turn over in his grave.

For the first three years of our marriage our income averaged a little more than $20, 000 a year. We indulged in such luxuries as a baby and a trip to Europe, and always money seemed to come easier and easier with less and less effort, until we felt that with just a little more margin to come and go on, we could begin to save.

Plans

We left the Middle West and moved East to a town about fifteen miles from New York, where we rented a house for $300 a month. We hired a nurse for $90 a month; a man and his wife—they acted as butler, chauffeur, yard man, cook, parlor maid and chamber maid—for $160 a month; and a laundress, who came twice a week, for $36 a month. This year of 1923, we told each other, was to be our saving year. We were going to earn $24, 000, and live on $18, 000, thus giving us a surplus of $6, 600 with which to buy safety and security for our old age. We were going to do better at last.

Now as everyone knows, when you want to do better you first buy a book and print your name in the front of it in capital letters. So my wife bought a book, and every bill that came to the house was carefully entered in it, so that we could watch living expenses and cut them away to almost nothing—or at least to $1, 500 a month.

We had, however, reckoned without our town. It is one of those little towns springing up on all sides of New York which are built especially for those who have made money suddenly but have never had money before.

My wife and I are, of course, members of this newly rich class. That is to say, five years ago we had no money at all, and what we now do away with would have seemed like inestimable riches to us then. I have at times suspected that we are the only newly rich people in America, that in fact we are the very couple at whom all the articles about the newly rich were aimed.

Now when you say “newly rich” you picture a middle-aged and corpulent man who has a tendency to remove his collar at formal dinners and is in perpetual hot water with his ambitious wife and her titled friends. As a member of the newly rich class, I assure you that this picture is entirely libelous. I myself, for example, am a mild, slightly used young man of twenty-seven, and what corpulence I may have developed is for the present a strictly confidential matter between my tailor and me. We once dined with a bona fide nobleman, but we were both far too frightened to take off our collars or even to demand corned beef and cabbage. Nevertheless we live in a town prepared for keeping money in circulation.

When we came here, a year ago, there were, all together, seven merchants engaged in the purveyance of food—three grocers, three butchers and a fisherman. But when the word went around in food-purveying circles that the town was filling up with the recently enriched as fast as houses could be built for them, the rush of butchers, grocers, fishmen and delicatessen men became enormous. Trainloads of them arrived daily with signs and scales in hand to stake out a claim and sprinkle sawdust upon it. It was like the gold rush of ’49, or a big bonanza of the 70’s. Older and larger cities were denuded of their stores. Inside of a year eighteen food dealers had set up shop in our main street and might be seen any day waiting in their doorways with alluring and deceitful smiles.

Having long been somewhat overcharged by the seven previous food purveyors we all naturally rushed to the new men, who made it known by large numerical signs in their windows that they intended practically to give food away. But once we were snared, the prices began to rise alarmingly, until all of us scurried like frightened mice from one new man to another, seeking only justice, and seeking it in vain.

Great Expectations

What had happened, of course, was that there were too many food purveyors for the population. It was absolutely impossible for eighteen of them to subsist on the town and at the same time charge moderate prices. So each was waiting for some of the others to give up and move away; meanwhile the only way the rest of them could carry their loans from the bank was by selling things at two or three times the prices in the city fifteen miles away. And that is how our town became the most expensive one in the world.

Now in magazine articles people always get together and found community stores, but none of us would consider such a step. It would absolutely ruin us with our neighbors, who would suspect that we actually cared about our money. When I suggested one day to a local lady of wealth—whose husband, by the way, is reputed to have made his money by vending illicit liquids—that I start a community store known as “F. Scott Fitzgerald—Fresh Meats,” she was horrified. So the idea was abandoned.

But in spite of the groceries, we began the year in high hopes. My first play was to be presented in the autumn, and even if living in the East forced our expenses a little over $1, 500 a month, the play would easily make up for the difference. We knew what colossal sums were earned on play royalties, and just to be sure, we asked several playwrights what was the maximum that could be earned on a year’s run. I never allowed myself to be rash. I took a sum half-way between the maximum and the minimum, and put that down as what we could fairly count on its earning. I think my figures came to about $100, 000.

It was a pleasant year; we always had this delightful event of the play to look forward to. When the play succeeded we could buy a house, and saving money would be so easy that we could do it blindfolded with both hands tied behind our backs.

As if in happy anticipation we had a small windfall in March from an unexpected source—a moving picture—and for almost the first time in our lives we had enough surplus to buy some bonds. Of course we had “my” bond, and every six months I clipped the little coupon and cashed it, but we were so used to it that we never counted it as money. It was simply a warning never to tie up cash where we couldn’t get at it in time of need.

No, the thing to buy was Liberty Bonds, and we bought four of them. It was a very exciting business. I descended to a shining and impressive room downstairs, and under the chaperonage of a guard deposited my $4, 000 in Liberty Bonds, together with “my” bond, in a little tin box to which I alone had the key.

Less Cash Than Company

I left the bank, feeling decidedly solid. I had at last accumulated a capital. I hadn’t exactly accumulated it, but there it was anyhow, and if I had died next day it would have yielded my wife $212 a year for life—or for just as long as she cared to live on that amount.

“That,” I said to myself with some satisfaction, “is what is called providing for the wife and children. Now all I have to do is to deposit the $100, 000 from my play and then we’re through with worry forever.”

I found that from this time on I had less tendency to worry about current expenses. What if we did spend a few hundred too much now and then ? What if our grocery bills did vary mysteriously from $85 to $165 a month, according as to how closely we watched the kitchen? Didn’t I have bonds in the bank? Trying to keep under $1, 500 a month the way things were going was merely niggardly. We were going to save on a scale that would make such petty economies seem like counting pennies.

The coupons on “my” bond are always sent to an office on lower Broadway. Where Liberty Bond coupons are sent I never had a chance to find out, as I didn’t have the pleasure of clipping any. Two of them I was unfortunately compelled to dispose of just one month after I first locked them up. I had begun a new novel, you see, and it occurred to me it would be much better business in the end to keep at the novel and live on the Liberty Bonds while I was writing it. Unfortunately the novel progressed slowly, while the Liberty Bonds went at an alarming rate of speed. The novel was interrupted whenever there was any sound above a whisper in the house, while the Liberty Bonds were never interrupted at all.

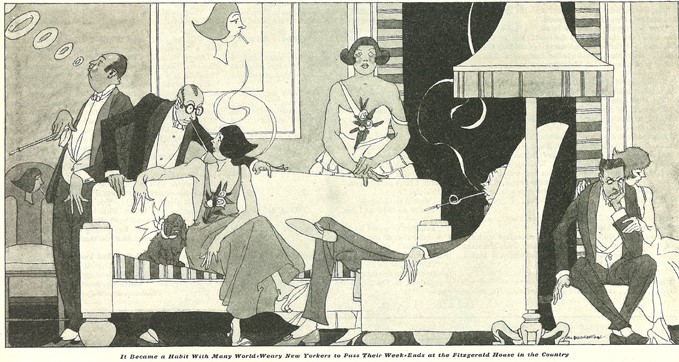

And the summer drifted too. It was an exquisite summer and it became a habit with many world—weary New Yorkers to pass their week-ends at the Fitzgerald house in the country. Along near the end of a balmy and insidious August I realized with a shock that only three chapters of my novel were done—and in the little tin safety-deposit vault, only “my” bond remained. There it lay—paying storage on itself and a few dollars more. But never mind; in a little while the box would be bursting with savings. I’d have to hire a twin box next door.

But the play was going into rehearsal in two months. To tide over the interval there were two courses open to me—I could sit down and write some short stories or I could continue to work on the novel and borrow the money to live on. Lulled into a sense of security by our sanguine anticipations I decided on the latter course, and my publishers lent me enough to pay our bills until the opening night.

So I went back to my novel, and the months and money melted away; but one morning in October I sat in the cold interior of a New York theater and heard the cast read through the first act of my play. It was magnificent; my estimate had been too low. I could almost hear the people scrambling for seats, hear the ghostly voices of the movie magnates as they bid against one another for the picture rights. The novel was now laid aside; my days were spent at the theater and my nights in revising and improving the two or three little weak spots in what was to be the success of the year.

The time approached and life became a breathless affair. The November bills came in, were glanced at, and punched onto a bill file on the bookcase. More important questions were in the air. A disgusted letter arrived from an editor telling me I had written only two short stories during the entire year. But what did that matter? The main thing was that our second comedian got the wrong intonation in his first act exit line.

The play opened in Atlantic City in November. It was a colossal frost. People left their seats and walked out, people rustled their programs and talked audibly in bored impatient whispers. After the second act I wanted to stop the show and say it was all a mistake but the actors struggled heroically on.

There was a fruitless week of patching and revising, and then we gave up and came home. To my profound astonishment the year, the great year, was almost over. I was $5, 000 in debt, and my one idea was to get in touch with a reliable poorhouse where we could hire a room and bath for nothing a week. But one satisfaction nobody could take from us. We had spent $36, 000, and purchased for one year the right to be members of the newly rich class. What more can money buy?

Taking Account of Stock

The first move, of course, was to get out “my” bond, take it to the bank and offer it for sale. A very nice old man at a shining table was firm as to its value as security, but he promised that if I became overdrawn he would call me up on the phone and give me a chance to make good. No, he never went to lunch with depositors. He considered writers a shiftless class, he said, and assured me that the whole bank was absolutely burglarproof from cellar to roof.

Too discouraged even to put the bond back in the now yawning deposit box, I tucked it gloomily into my pocket and went home. There was no help for it—I must go to work. I had exhausted my resources and there was nothing else to do. In the train I listed all our possessions on which, if it came to that, we could possibly raise money. Here is the list:

- 1 Oil stove, damaged.

- 9 Electric lamps, all varieties.

- 2 Bookcases with books to match.

- 1 Cigarette humidor, made by a convict.

- 2 Framed crayon portraits of my wife and me.

- 1 Medium-priced automobile, 1921 model.

- 1 Bond, par value $1, 000; actual value unknown.

“Let’s cut down expenses right away,” began my wife when I reached home. “There’s a new grocery in town where you pay cash and everything costs only half what it does anywhere else. I can take the car every morning and—”

“Cash!” I began to laugh at this. “Cash!”

The one thing it was impossible for us to do now was to pay cash. It was too late to pay cash. We had no cash to pay. We should rather have gone down on our knees and thanked the butcher and grocer for letting us charge. An enormous economic fact became clear to me at that moment—the rarity of cash, the latitude of choice that cash allows.

“Well,” she remarked thoughtfully, “that’s too bad. But at least we don’t need three servants. We’ll get a Japanese to do general housework, and I’ll be nurse for a while until you get us put of danger.”

“Let them go?” I demanded incredulously. “But we can’t let them go! We’d have to pay them an extra two weeks each. Why, to get them out of the house would cost us $125—in cash! Besides, it’s nice to have the butler; if we have an awful smash we can send him up to New York to hold us a place in the bread line.”

“Well, then, how can we economize?”

“We can’t. We’re too poor to economize. Economy is a luxury. We could have economized last summer—but now our only salvation is in extravagance.”

“How about a smaller house?”

“Impossible! Moving is the most expensive thing in the world; and besides, I couldn’t work during the confusion. No,” I went on, “I’ll just have to get out of this mess the only way I know how, by making more money. Then when we’ve got something in the bank we can decide what we’d better do.”

Over our garage is a large bare room whither I now retired with pencil, paper and the oil stove, emerging the next afternoon at five o’clock with a 7, 000-word story. That was something; it would pay the rent and last month’s overdue bills. It took twelve hours a day for five weeks to rise from abject poverty back into the middle class, but within that time we had paid our debts, and the cause for immediate worry was over.

But I was far from satisfied with the whole affair. A young man can work at excessive speed with no ill effects, but youth is unfortunately not a permanent condition of life.

I wanted to find out where the $36, 000 had gone. Thirty-six thousand is not very wealthy—not yacht-and-Palm-Beach wealthy—but it sounds to me as though it should buy a roomy house full of furniture, a trip to Europe once a year, and a bond or two besides. But our $36, 000 had bought nothing at all.

So I dug up my miscellaneous account books, and my wife dug up her complete household record for the year 1923, and we made out the monthly average. Here it is:

| HOUSEHOLD EXPENSES | Apportioned per month | |

|---|---|---|

| Income tax | $ | 198.00 |

| Food | $ | 202.00 |

| Rent | $ | 300.00 |

| Coal, wood, ice, gas, light, phone and water | $ | 114.50 |

| Servants | $ | 295.00 |

| Golf clubs | $ | 105.50 |

| Clothes—three people | $ | 158.00 |

| Doctor and dentist | $ | 42.50 |

| Drugs and cigarettes | $ | 32.50 |

| Automobile | $ | 25.00 |

| Books | $ | 14.50 |

| All other household expenses | $ | 112.50 |

| Total | $ | 1,600.00 |

“Well, that’s not bad,” we thought when we had got thus far. “Some of the items are pretty high, especially food and servants. But there’s about everything accounted for, and it’s only a little more than half our income.”

Then we worked out the average monthly expenditures that could be included under pleasure.

| Hotel bills—this meant spending the night or charging meals in New York | $ | 51.00 |

| Trips—only two, but apportioned per month | $ | 43.00 |

| Theater tickets | $ | 55.00 |

| Barber and hairdresser | $ | 25.00 |

| Charity and loans | $ | 15.00 |

| Taxis | $ | 15.00 |

| Gambling—this dark heading covers bridge, craps and football bets | $ | 33.00 |

| Restaurant parties | $ | 70.00 |

| Entertaining | $ | 70.00 |

| Miscellaneous | $ | 23.00 |

| Total | $ | 400.00 |

|---|---|---|

Some of these items were pretty high. They will seem higher to a Westerner than to a New Yorker. Fifty-five dollars for theater tickets means between three and five shows a month, depending on the type of show and how long it’s been running. Football games are also included in this, as well as ringside seats to the Dempsey-Firpo fight. As for the amount marked “restaurant parties”—$70 would perhaps take three couples to a popular after-theater cabaret—but it would be a close shave.

We added the items marked “pleasure” to the items marked “household expenses,” and obtained a monthly total.

“Fine,” I said. “Just $3, 000. Now at least we’ll know where to cut down, because we know where it goes.”

She frowned; then a puzzled, awed expression passed over her face.

“What’s the matter?” I demanded. “Isn’t it all right? Are some of the items wrong?”

“It isn’t the items,” she said staggeringly; “it’s the total. This only adds up to $2, 000 a month.”

I was incredulous, but she nodded.

“But listen,” I protested; “my bank statements show that we’ve spent $3, 000 a month. You don’t mean to say that every month we lose $1, 000 dollars?”

“This only adds up to $2, 000,” she protested, “so we must have.”

“Give me the pencil.”

For an hour I worked over the accounts in silence, but to no avail.

“Why, this is impossible!” I insisted. “People don’t lose $12, 000 in a year. It’s just—it’s just missing.”

There was a ring at the doorbell and I walked over to answer it, still dazed by these figures. It was the Banklands, our neighbors from over the way.

“Good heavens!” I announced. “We’ve just lost $12, 000!”

Bankland stepped back alertly.

“Burglars?” he inquired.

“Ghosts,” answered my wife.

Mrs. Bankland looked nervously around.

“Really?”

We explained the situation, the mysterious third of our income that had vanished into thin air.

“Well, what we do,” said Mrs. Bankland, “is, we have a budget.”

“We have a budget,” agreed Bankland, “and we stick absolutely to it. If the skies fall we don’t go over any item of that budget. That’s the only way to live sensibly and save money.”

“That’s what we ought to do,” I agreed.

Mrs. Bankland nodded enthusiastically.

“It’s a wonderful scheme,” she went on. “We make a certain deposit every month, and all I save on it I can have for myself to do anything I want with.”

I could see that my own wife was visibly excited.

“That’s what I want to do,” she broke out suddenly. “Have a budget. Everybody does it that has any sense.”

“I pity anyone that doesn’t use that system,” said Bankland solemnly. “Think of the inducement to economy—the extra money my wife’ll have for clothes.”

“How much have you saved so far?” my wife inquired eagerly of Mrs. Bankland.

“So far?” repeated Mrs. Bankland. “Oh, I haven’t had a chance so far. You see we only began the system yesterday.”

“Yesterday!” we cried.

“Just yesterday,” agreed Bankland darkly. “But I wish to heaven I’d started it a year ago. I’ve been working over our accounts all week, and do you know, Fitzgerald, every month there’s $2, 000 I can’t account for to save my soul.”

Headed Toward Easy Street

Our financial troubles are now over. We have permanently left the newly rich class and installed the budget system. It is simple and sensible, and I can explain it to you in a few words. You consider your income as an enormous pie all cut up into slices, each slice representing one class of expenses. Somebody has worked it all out; so you know just what proportion of your income you can spend on each slice. There is even a slice for founding universities, if you go in for that.

For instance, the amount you spend on the theater should be half your drug-store bill. This will enable us to see one play every five and a half months, or two and a half plays a year. We have already picked out the first one, but if it isn’t running five and a half months from now we shall be that much ahead. Our allowance for newspapers should be only a quarter of what we spend on self-improvement, so we are considering whether to get the Sunday paper once a month or to subscribe for an almanac.

According to the budget we will be allowed only three-quarters of a servant, so we are on the lookout for a one-legged cook who can come six days a week. And apparently the author of the budget book lives in a town where you can still go to the movies for a nickel and get a shave for a dime. But we are going to give up the expenditure called “Foreign missions, etc.,” and apply it to the life of crime instead. Altogether, outside of the fact that there is no slice allowed for “missing” it seems to be a very complete book, and according to the testimonials in the back, if we make $36, 000 again this year, the chances are that we’ll save at least $35, 000.

“But we can’t get any of that first $36, 000 back,” I complained around the house. “If we just had something to show for it I wouldn’t feel so absurd.”

My wife thought a long while.

“The only thing you can do,” she said finally, “is to write a magazine article and call it How to Live on $36, 000 a Year.”

“What a silly suggestion!” I replied coldly.

Editorial

This essay was written for The Saturday Evening Post, where it was printed April 5, 1924. As it at least lightly suggests, it had its source in the six months of driving work between November, 1923, and April, 1924, during which Fitzgerald produced eleven short stories and earned something over $17, 000 to pay off the debts that had accumulated during the previous year, especially during the production of The Vegetable. “I really worked hard as hell last winter,” he said of this period in a letter to Edmund Wilson “—but it was all trash and it nearly broke my heart as well as my iron constitution.” This comment is an exaggerated expression of Fitzgerald’s lifelong desire to be a serious writer and an orderly man. This essay’s amused sense of his helplessness as one of the “newly rich” is about equally exaggerated, partly, no doubt, because that tone was the right one for the Post, but mainly, I think, because his characteristic sense of the representative nature of his own case and his acute insight into the attitudes of the group he represented demanded this kind of irony.

Few writers have put the comic helplessness of the newly rich in our fluid and—for that very reason—etiquette-ridden society so well. How clearly he understands the seduction of success (“Why, it was impossible—that I should be poor! I was living at the best hotel in New York!”), how well he knows that most of the newly rich are “mild, slightly used young men” with perfectly good manners, how clearly he sees the absurdity of budgets which allow you “to get the Sunday paper once a month or to subscribe for an almanac.” This is the real history of a group (it can hardly be called a class in a society in which no group is stable long enough to acquire continuity) to which at one time or another nearly every one in American society has belonged, though usually in a less spectacular and therefore less classically complete way than Fitzgerald.

Published in The Saturday Evening Post magazine (5 April 1924).

Illustrations by M. L. Blumenthal.