Beautiful Fools

by R. Clifton Spargo

9

THE WOMAN TOEING THE EDGE OF THE PROMONTORY WAS HIS WIFE, her posture balletic, back held erect in a line with her heels. From this distance she seemed supple, lithe, as irrepressible as in the days when she had trained for dance with steadfast indifference to body and mind. In the gusting of a coastal wind, he put a hand to his hat, then allowed his eyes once more to climb and behold Zelda’s crimson-suited body framed by empty sky, hair blowing, face turned into the wind, waiting until it should subside so that she might plunge into the ocean. She was brave, maybe even foolhardy, and he swelled with admiration for her.

“Are you sure this is safe?” the Frenchwoman asked, standing beside him as his wife rotated away from the water, spotted him below on the beach, and raised her arm in a stilted motion not unlike a salute. She was thrilled at having found this high place, eager as always to show off for him, but for a split second—instantly he beat back the thought—it was as if she were waving goodbye. Several feet behind her stood the Spaniard, his naked skin almost pale in the sunlight. He too was prepared to dive into the ocean, but only after Zelda had taken her turn and brought the arc of the morning’s chase to its rightful end.

***

It had started in the hotel room after she gave him the St. Lazarus medallion and announced that she needed to borrow more of their vacation money because surprises were so very expensive. Not to worry, in the days to come she would prove herself frugal, only let her have today. When he gave in, she let out a squeal of excitement.

“Oh, you’ll see, it will be such fun. You’ll keep an open mind and remember we’re on holiday and in the end you always like the things I find for us to do.”

Did he, was she so certain?

“Oh, yes, you do, you will, you always do, I’m sure of it.”

Her enthusiasm was like a primitive grace ravaging everything in its path. So he handed over the pesos in his possession, and she said, please, sir, more, and he gave her another wad of bills. In the courtyard half an hour later he crossed in front of the fountain misting in his face and through the archway of funneled wind to emerge squinting into the speckled light. No sign of his wife at the reception desk. No sign of the Frenchwoman or her refugee cousin.

“Senor Fitzgerald,” the man behind the desk called, holding up a slip of paper, “esto llego hace poco para usted.”

It was a cable, and Scott rested his forearms on the reception desk to read it, first surveying the lobby with its spare yet handsome furniture, several benches and chairs and a long bureau, all carved from a wood so dark it was almost black. It didn’t surprise him that Mateo Cardona had managed to track him to this resort on the peninsula, even though he couldn’t recall ever mentioning their next destination. In the hallway of the Ambos Mundos, Mateo had spoken of Saturday night’s event as “under control” and yet “far from settled,” Scott wondering how it could be both things at once. “The wounded man has died, Scott,” Mateo said. Under circumstances such as these, the police were inclined to use any means necessary to acquire a verdict. Someone might remember, even if it wasn’t the entire truth, that Zelda had provoked the fight by rushing through the crowd and crashing into the man who’d cursed her. “Let me take care of this for you,” Mateo had insisted.

As Scott now skimmed the contents of the cable, he took in key phrases—“several matters unresolved,” “not informed of your plans,” “next steps to be considered”—and he understood that Mateo was unhappy with him for leaving Havana without notice. The cable concluded with news that a messenger would be dispatched to Varadero, maybe tomorrow morning, maybe this evening, Scott should remain on the lookout.

“Too bad we’ll be gone all day,” Scott said to himself. Still, he jotted down Mateo’s telephone number and address in his Moleskine, just in case, then tore the cable in half, sliding it across the dark granite surface toward the clerk.

“Entiendo, senor,” the clerk said. “A la basura.” He made a motion with his arm as though tossing an item into a basket, and Scott nodded his assent.

No sign of Zelda in front of the building, so Scott exited at the rear through French doors that opened onto a dirt and cinder pathway winding through coconut palms toward the beach, his breathing raspy, his stomach queasy, though he wasn’t as bad off as he might have been. Too much food in his system for this hour of the day, but he couldn’t have refused Zelda’s impromptu banquet. In the pockets of his light tweed jacket was enough Benzedrine and chocolate to keep three men awake for several days, and he promised himself to use the medicine sparingly. Fingers plunged into an outside pocket, he broke off a chunk of a Baker’s German’s sweet chocolate bar, lifting the rectangle to his nose to detect its malty fragrance before folding it in one sharp snap into his mouth, letting the chocolate sit on his tongue.

Halfway to the beach he spotted her, perched on a knoll that rose like a burial mound amid a small cluster of columnar palms, at her side Maryvonne, Aurelio, and several horses.

“Can you guess what the surprise is now?” she asked.

“Let me see,” he said, holding a thumb and two fingers to his forehead in imitation of a clairvoyant, “you and I are going to watch Maryvonne and Aurelio race horses along the beach?”

“So you’ve already noticed the horses?”

“Hard to miss them.”

“How did you know they were ours? You didn’t think for a second they might belong to someone else?”

“Well, Aurelio is holding the reins.”

“This is the plan of your wife and mine also,” Aurelio said, as if he wished to go on record ahead of time as a neutral party.

“There are only three horses,” Scott remarked.

“It is all that is ’vailable,” Maryvonne said, the last word pronounced as if she were mimicking the term valuable.

But Zelda had thought of everything, deciding they would rotate seating throughout the day so that each woman might take turns riding with each man.

“Some horses do not like to carry two people at once,” Aurelio protested.

“That is why we have the large saddle,” Zelda said, annoyed by the Spaniard’s prosaic imagination. “Scott and I will share a horse for the first rotation.”

One of the horses was a bay gelding thoroughbred, the other two of no particular breed, including the medium-sized palomino with an ivory mane that he and Zelda were to mount.

“He’s the docile but hardy one,” Zelda said. “The owner often rides him with his young daughter seated on the saddle before him.”

“That is not the same thing,” Aurelio insisted.

“It will be fine,” Maryvonne interjected. “Zelda and I are small, like children.”

Scott walked toward the animal, wishing his wife might have consulted him about the horseback riding, and that he in turn might have put her off a day or two, until he was sturdier. Still running short on sleep, hands jittery from weeks of hard drinking, he inserted his left foot in the stirrup, reached his hand to the pommel, then swung himself up onto the saddle. His chest tightened, and he could feel the pinch in his lungs as though someone were thumbing an internal bruise. He didn’t like heights of any kind, not airplanes, not diving boards, not even horses. In defiance of his fears he sometimes performed reckless acts, such as that ill-advised Olympic-style swan dive off a fifteen-foot diving board in Asheville a few years ago, inspired by (what else) a woman, resulting (no surprise here either) in a shattered clavicle and months of drunken convalescence. He let his thoughts race ahead to a full day of riding in the sun, in search of beaches and high places over the water, dreading the hours during which he would have to put up a brave front. Fortunately—if not for this provision, he might have despaired in advance—he had stowed a flask of Martell’s in the breast pocket of his sport coat.

“Well done, Scott,” Aurelio said, praising his new friend’s mount as he held the second horse, a black mare, still for Maryvonne, then scaled the bay gelding in one swift motion without provoking so much as a flinch.

“Hold her still, Scott,” Zelda said as the palomino took a step back. Scott clenched the reins to calm the horse, now lowering his free arm so that Zelda might grab hold and hoist herself into the air in a dancer’s leap. In an instant she sat in the saddle, preposterously facing him, her orange and white muslin dress bunched over the pommel, her crotch snug against his.

“Zelda, we can’t ride like this.”

She peered hard into his eyes as if assessing his elan vital, sniffing out symptoms of alcoholic or tubercular deterioration, then playfully she licked the corner of his lip.

“Sweet chocolate,” she remarked. Had he brought any to share?

“Of course.”

“Nevertheless we’re stopping at a market for picnic items.” She and Maryvonne had already purchased two bottles of wine from the hotel and stored them in Aurelio’s saddlebag.

“You’ve accounted for everything except how I’m supposed to direct this horse with my wife riding in my lap.”

“You’re not,” she said, then told him he would have to dismount so she could turn around in the saddle.

“But Zelda, that makes no sense,” he muttered. “Why did I get in the saddle first?”

“I was wondering that myself,” she said.

He could tell that she was in a buoyant and willful mood, and it was useless to argue with her, so he draped the reins over her forearm, slipping his feet out of the stirrups to dismount the horse. The horse skittered forward, expressing its displeasure, but Scott retrieved the reins from Zelda to still the horse. He watched his wife place her hands between her thighs, then lift the flaps of her dress so that she might swing her left leg out from the horse, rotating her body by moving hand over hand in the center of the saddle, her weight balanced on those well-developed dancer’s triceps as she made the 180-degree turn. “Are you pleased?” she whispered midmotion. About the horses, she meant, he wasn’t angry that she’d gone ahead and arranged everything without him. Soon she had ensconced herself face-forward in the saddle, inviting him to remount the horse, posting in the saddle as he settled in behind her and then lowering herself, her derriere pressing against his mildly stirred genitalia, her neck craning to ask her question again.

“It’s a nice surprise,” he said. “I want you to do what brings you pleasure.”

“I know you don’t love riding the way I do, so we’ll ride gently at first.”

Dressed in snug canvas trousers, boots, and a bright red shirt, Aurelio rode the gelding with skill, directing them up the beach into the winds, swinging his outside leg back and prodding the horse with his heel, urging it into a canter. Maryvonne, also dressed appropriately in black riding pants and a loose white blouse, could not get her mare up to speed. After pressing the mare with her heel, she snapped the reins against the withers repeatedly, but without result. Only Scott was overdressed for the outing, and he regretted that he hadn’t insisted on running back to the room for a change of clothes.

“He rides well, don’t you think? He trained for the cavalry,” Zelda said, and Scott tried to remember whether he had read anywhere about the Republicans assembling a cavalry.

Zelda crouched forward, one hand on the reins while she ran the other forward over the horse’s silky golden neck, stretching her leg over Scott’s in an effort to prod the horse’s haunches. The jolt of acceleration caused Scott to lose balance, swaying to the side, so that he had to right himself by inching forward in the saddle and wrapping a forearm around his wife’s waist, struggling to find the horse’s center of gravity.

Zelda let out a laugh, whinnying and zestful. She loved speed in a way he did not; she loved any occasion to test her body and her nerve. She rode with a destination in mind, one she would not share despite several queries from him. For the moment she concentrated only on passing Maryvonne, after that on catching up with Aurelio, who rode the bay gelding with manly elegance, the horse’s hooves kicking up sand, the beach ahead resplendent in sunlight, empty of sunbathers. Zelda guided their horse close to the water where the sand was damp and firm, and soon she was shouting to Aurelio as they drew near, “Do you remember where we turn?”

“Any one of the dirt roads,” he called back.

“Zelda, where are we going?” Scott shouted into the wind.

“Why are you against surprises?” She laughed as she overtook Aurelio and the slowing gelding, and next she turned their horse with a single snap of the reins onto a dirt path to ride between modest stone bungalows and cottages with thatched roofs into the center of a small village. Aurelio, somewhere back where the beach met the dirt road, waited on Maryvonne.

Scott discerned the small church with its modified mission front as they cleared an open-air market that consisted of several huts side by side, the posts of one hut all but indistinguishable from those of the next, a long row of them running up into the straw and frond ceilings, beneath which merchants stood hawking everything from fruit and live chickens to pottery, colorfully embroidered peasant shirts, and silver jewelry.

“I think we should buy you a proper hat,” Zelda said. “In that silly tweed you resemble an English lord taking survey of the manor.”

For a second Scott’s thoughts ran across a continent to Sheilah, his girl from England, marooned in California with her great secret. Zelda’s remark made him think of Sheilah’s elaborate cover story, the illustriously invented ancestry backed by the picture she’d once showed him of an English lord propped on a horse who was supposed to be her uncle, how after weeks of his poking for details she’d broken down and let him in on the enigmatic truth: she had been reared in a British orphanage, a Jewish waif forsaken for eight years by a mother too destitute to raise the child herself. She was a self-made woman in every sense of the term, including the fantastic lineage concocted to procure a place on the London stage, later a husband (whom she quickly divorced), and still later work as a Hollywood gossip columnist. No one else knew, not her ex-husband, not the real British lord with whom she had months ago broken off an engagement to become Scott’s full-time mistress. Some honor, he thought, and now I’ve left her. But he couldn’t think of her just now—that was over, most likely.

“A lord pompously propped on his fine pony,” Zelda said, “while he checks on the good-for-nothing Irish serfs.”

“Your point is that the serfs or the indigenous populace might be less likely to resent me if I buy one of their hats?”

“Honestly, Scott, I’m worried that your stodgy old cap won’t shield you from the cruel sun, but it’s simply more efficient to appeal to your vanity than to your health.”

“Tell me about the church,” he said.

“Well, it’s on the scale of chapel more than church, don’t you think,” she said, informing him that she had scouted it earlier this morning. “It was built only this past year, funded by the du Pont family, if I understand correctly, Irenee du Pont, who has a place here on the peninsula.”

The facade of the church, constructed of large rectangular stones, had battered sides rising to a gable, on top of which there was a small altarlike form encasing the bell.

After the European couple caught up with them and all four tourists dismounted their horses and tied them up, Aurelio refused to enter the sacred building. A priest emerged from behind the church, one of the villagers having run off to inform him of the arrival of guests, and he smiled for the tourists, speaking in blunt provincial Spanish, Maryvonne translating.

“He would like to show us the inside,” she said.

“Oh, yes, gracias, monsieur. Wait,” Zelda said, mixing Spanish and French. “Excusez-moi, gracias, Padre.”

The priest guided the women past the diminutive buttresses toward an entrance on the side of the church near a cubic stone chapter house connected to the back of the church, Scott trailing them, observing Aurelio still planted, stiff backed, not far from the horses.

“Zelda,” Scott called, “I’ll catch up with you in a minute.”

His words drew the priest’s attention to the two men, and as the duly appointed liaison between God and men, even perhaps between men and their own souls, he issued a second invitation.

“Dios y yo,” Aurelio called out, “hemos elegido sendas distintas.”

The priest flinched at the staunch rejection of God’s hospitality, looking around him for local villagers, obviously embarrassed.

“El nunca te abandonara, cualquiera sea tu senda,” the priest said, bowing respectfully, then extending his arms to either side of him to lead the women inside the church.

“As you wish to believe, Padre,” Aurelio answered curtly.

“Aurelio,” Zelda called, intervening, “remember, you must go to the market to obtain the items for our picnic.”

“Gladly, Mrs. Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald.”

“Why did you tell him you had rejected God?” Scott asked his companion once the priest and the women were out of hearing distance.

“Your Spanish is not very good, my friend,” Aurelio said. “Not what I said, though it is true enough. Perhaps I would be more precise if I say, God, he has rejected my people.”

“I get it,” Scott said, thinking of the lost war in Spain. “You’ve a quarrel with the Church.”

“Not personal,” Aurelio said. “The pelea, perhaps you say complaint, it belong to all of Spain. You are faithful man, piadoso—if so, if I insult you, for this I am sorry, truly.”

“Not religious, not insulted,” Scott said. He pulled the flask of Martell’s from his jacket, looking over his shoulder to ascertain that Zelda had in fact entered the church and could no longer see him, then extended the flask to Aurelio. After the Spaniard took a polite sip and handed it back, Scott tilted his chin for a slow, pleasurable swig.

“Well, I must check on them,” Scott said, half-inclined to visit the market with Aurelio and stand in solidarity against the Catholic Church for having thrown in with Fascists, but instead he entered the small church where Zelda knelt at the altar as though she were a communicant waiting on the host. It caught him by surprise every time, his wife’s newfound piety. Studying her face, her chin burrowed in her breast, he witnessed someone longing for a peace that refused to overtake her. Scott envisioned thousands of mothers and wives kneeling on prie-dieux, whispering in pews across Spain, petitioning for the return of husbands, sons, and fathers they knew to be lost, silently pleading that an entire three years of ruthless violence might be undone.

Before they could leave, Zelda insisted on lighting several votive candles. They stood beneath the church’s exposed-timber ceiling, reminiscent of colonial missions, and as she implored him in front of the priest to make a donation, he tried to remember when her modes of prayer had become so Catholic. As a young couple they used to attend services together, visiting St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York, where they had been married, later appreciating the High Mass at Notre Dame, which despite her Protestant upbringing she relished for its pomp and majesty. Still, prayer was something they rarely discussed. They were acolytes of a post-religious era, in flight from the strictures of the Catholic and Protestant God, all those teetotalers, prohibitionists, anti-petting prudes, the generally puritanical populace—it was hard to imagine they might ever look back.

***

Aurelio, with his arm full of groceries, met them in the shade where they had tied up the horses.

“Why is that old woman staring at me?” Zelda asked, and Scott looked across the road at a woman in a frock and kerchiefed head, who, with her dark, sun-wrinkled skin and broadly bridged nose, might have hailed from any sunny climate from almost any period in history.

“She believe with all her heart it is something she must say to you,” Aurelio said.

“How do you mean?” Scott said, as Zelda asked simultaneously, “What can she have to say to me?”

“We have right to disobey her,” Aurelio proposed reasonably.

“Doubtless she’s a fortuneteller of some sort,” Scott said. “On the prowl for customers.”

“I know that, Scott,” Zelda snapped, addressing herself again to Aurelio. “Why do you say must?”

“Her words, not mine,” Aurelio said. “‘Tengo que hablar con la dona elegante,’ she say. It is very important. Scott is right. Is the way of women who speak to the spirit world, it is true. Always some message must be translated, if you pay, only if you pay them.”

“Perhaps she meant me,” Maryvonne laughed. “I am also elegant.”

Scott was grateful for Maryvonne’s courteous instincts, for the effort to distract Zelda—as a trained nurse, the Frenchwoman could detect the symptoms of an obsessive personality—but Aurelio wouldn’t eat his words.

“She mean Zelda, I am sure.”

Scott looked across the street and saw the old woman’s hand held open before her, several fingers curled in a gesture of invitation, neither the hand nor fingers in motion. How long had she been doing that?

“I won’t speak with her,” Zelda said, the peace she had achieved minutes ago inside the church already evaporating.

“Zelda is right. It is best to speak to the spirit world,” Maryvonne suggested, “only in God’s house.”

Aurelio untied the horses.

“I have watered horses,” he said.

Scott and Zelda were to ride solo for the next leg of the trip. Immediately she seized the reins of the bay gelding from Aurelio. The Spaniard claimed the palomino for Maryvonne and himself, handing Scott the reins of the third horse, reasoning that since the mare was the weakest, someone should always ride her solo.

“That way there is better chance to keep up,” he explained.

Zelda nicknamed Scott’s horse “the old nag” and the name stuck the rest of the day. For as long as he rode the mare, Scott sympathized with her, perhaps detecting something of his own ragged state in her plight, though he wouldn’t have put it that way. What he told himself was simpler: he was far from a skillful rider and didn’t require a good horse, so why not this tired black mare?

Zelda took the lead, enjoying the lively athleticism of the gelding, and Aurelio kept pace for a while, then dropped behind to see how Scott was faring.

“Does she have any idea where she’s headed?” Scott asked.

“Le pretre, he give us instructions,” Maryvonne said.

“That was kind of him,” Scott replied, “but where to, exactly?”

“Zelda, she ask about a place for diving,” Maryvonne said. “The father just smile, then say, ‘Je sais l’endroit ideal,’ so perhaps it is a blessed and blissful place.”

The Europeans tried to engage Scott in conversation about his wife, her derring-do, her skill on horses and prowess at dancing, but it alarmed him to learn she’d spoken to them about the ballet, and he was deaf to their words as he strained to keep track of Zelda up ahead. The Europeans did manage to extract one story from him. It was of a young Zelda, still a girl of eighteen, during the era of their multiply broken, narrowly repaired engagements (the European couple interrupted, asking for details about the engagements, but Scott put them off). Again he saw the beautiful Zelda Sayre, red-gold hair to her neck sweeping outward in bold wings, her round cheeks flushed pink, the most pink-white girl imaginable. The incident he recited for them? Zelda, flouting Montgomery customs with customary zeal, accused of lewd behavior at a holiday ball, maybe for close dancing, maybe for showing more than a little leg, he couldn’t remember what exactly. Pulled from the dance floor a fourth or fifth time, she found a sprig of mistletoe, attached it to her skirt tails, and for her last dance waved her rear end at the chaperones like a peacock, letting them know, please excuse his French, what part of her precious person they could kiss.

From time to time Zelda raced back on the gelding to check on them, inquiring, “How’s the old nag holding up?” She made sure no one second-guessed her command of the expedition, declaring, “It’s not far now,” then sprinted ahead until she and her horse were one faint image on the horizon.

Ultimately, she deposited them on a stretch of beach at the far end of the peninsula just shy of Hicacos Point, the priest having promised her it was secluded, the promontory good for diving, the water deep enough and without rocks. She had dismounted and tied her horse to a tree, already disrobed by the time they approached, in the midst of donning her crimson bathing suit under a date palm, her dimpled lower back visible as she pulled the suit over her waist and the straps onto her shoulders. She announced that she was headed to the top of the cliff.

They should test the water first, Scott suggested.

The father, she said in French, had promised it was safe.

How could she be sure they’d found the right spot?

“Faith,” she assured him as she marched off.

He might have run after her, but there was little chance of changing her mind. He might have stripped and swum far out into the water beneath the promontory to assess the depth, checking for boulders, but he hadn’t taken a swim in two years.

“I will accompany her, my friend,” Aurelio said, beginning to undress beneath the tree to which he’d tied the palomino.

Scott felt remiss in the face of the Spaniard’s chivalry, but also exasperated by Zelda’s impulsiveness, by the effort entailed in merely keeping pace with her. So he let her climb the steep back of the crag until she was out of sight, with the naked Spaniard chasing after her. All that was left for Scott to do was to stand on the beach and murmur a small petition on his wife’s behalf to some saint in whom he no longer believed, wondering if the Lazarus he wore about his neck held province here, worried lest catastrophe once more befall a woman he’d watched ruin herself, repeatedly, for over a decade. The two figures eventually emerged atop the promontory.

***

The day was bright blue and warm and the wind carried the ocean rushing through you, vigorous, salty, but also entirely fresh because this far out on the peninsula everything swept from one narrow strip of beach to the opposite, a terse Atlantic wind whipping across dunes, beach brush, and tall grasses out onto the Caribbean. No fetid pools of backwater, nothing of the land to be gathered up and carried on the breeze—the wind was ocean and sky, nothing else.

“The sky is always so blue on our vacations,” she said, falling beside him, panting from her sprint across the beach, her wet body spraying him as she collapsed on the sand. Maybe thirty yards on, Maryvonne stood, shoes off, a pair of men’s shorts over her arm, her riding pants pulled up off her knees as she waded through the white-foamed scum of splintered waves to greet her husband when he emerged from the water.

“I’m surprised to find you sitting in the sun, and, look, I forgot all about the hat we were going to buy you earlier, you’ll be sunburnt by now, let me see.” Zelda rested her wet hand against his chin, depressing her thumb on his forehead and cheeks. “It’s all my fault.”

“Nonsense,” he said. “You look lovely and sun-kissed and happier than I’ve seen you in a long time.”

“You forget, that’s all,” she said, “how charming I can be, how much you like being with me when I’m happy and you’re all mine and nothing could ever make me happier than that you’re all mine and it is right now. Maybe you should take your pen out and write it down in that surly Moleskine. I worry about it, that you only retain the sufferings, never the joy, where’s the joy, Scott, there was also always so much joy, most of the time anyway.”

“I remember both in equal portions,” he said.

“Now you’re just being an ornerykins for no reason,” she said. “Why do you want to spoil everything? Tell me, did you watch me the whole time? Would you like to grade my form, and were you jealous thinking of me in the water naked with that handsome man?”

“You weren’t naked.”

“How can you be so sure? I might have been, I wanted to be, I love swimming naked in the water.”

“With strange, handsome men?”

“Don’t forget naked.”

“I noticed.”

“And why not?” she said. “He’s no threat to you. If I didn’t love you, he might be, but I do love you so, and haven’t any interest in men like him. Tell me, have you found my note yet?”

What on earth could she be talking about? He stopped himself, making sure not to let ire creep into his voice.

“Zelda, your mind’s too quick for me just now. Please slow down. Did you write me a note, and if so, when? While we were in the church? Are you aware that you never gave it to me?”

She laughed, twisting her head so that he could see the pleasure she took in his confused ignorance. She was eager for questions. This appetite for mystery or whatever it was alarmed him.

“Now that we’re on a beach discovered by me, ready to have a picnic lunch, we really are living so idyllically, don’t you think.” She was trying to get everything back at once. “There’s no reason for it to change, unless, of course, you spoil my day by not remembering the note.”

“Zelda, you never gave me a note.”

“How can you be so sure?”

Then he understood—she had passed the note to him in secret somehow. He began to search the outer pockets of his sport coat, rifling through the torn wrappers of chocolate bars, fumbling through pills, moving the search to inside pockets, plumbing his fingers down along the sides of the flask, unable to extract it for fear Zelda might notice, almost certain, though, that there was nothing else in the pocket. When he started in on his trousers, she let out a wicked laugh and he began to retrace his steps. His journal, of course. He pulled the Moleskine from the opposite breast pocket, cracking the binding to the most recent entry, where he discovered a piece of green stationery neatly creased in squares. He unfolded the stationery—her Salud de Schiaparelli floating up, that fragrance she’d asked him to procure for her only last year—to reveal a bold, unruly script, the rolling loveliness of the alphabet under her sway.

“Not here,” she said, and he looked up to see Maryvonne and Aurelio striding up the beach toward them, the Spaniard still nude. “Please, Scott,” she implored him, “you can’t read it in my presence—have you no sense of etiquette?”

“Apparently not,” he said. “Otherwise I’d most certainly be naked by now.”

“That would be delightful,” she said. “But don’t say anything to make him self-conscious.”

Aurelio stood before them, dangling his shorts from his fingers, lamenting that they had forgotten towels. Maryvonne ran back to one of the horses to grab the blanket, asking where she should spread it for the picnic.

“Near the trees,” Zelda said. “We could use some shade after all the riding.”

Scott wished the Spaniard would put some godforsaken clothes on. His skin was grayish white in the sunlight, his wine-blue veins running like dark rivulets beneath the surface of his fine limbs. Scott couldn’t help but lower his eyes to the man’s privates, the stem thick, purplish, and dormant, dangling over testicles that rounded into a bulbous pouch, the genitalia resembling nothing so much as a heart and an aorta, the body’s most essential muscle exposed. He couldn’t look away—that is, until he noticed the mangled right thigh, the bone-white, ridged lines where the shrapnel had torn into flesh and muscle, the scar in the shape of a country such as Chile, widening in the middle but narrowing again at the tips. Only when Aurelio detected Scott gaping at the scar did he turn away and walk up the beach; and, thankfully, by the time he rejoined the party on the blanket under the tree, he wore shorts that mostly covered his wound.

They lunched on salt-cured olives and baguettes onto which Zelda and Maryvonne laid slices of chorizo or cured Cuban ham, topped with a pungent local cheese. Scott could stomach no more than a few bites of his sandwich. No surprise there. He could rarely eat anything until evening. He was grateful, though, for the wine. It was a Torres dry white, which Aurelio retrieved from the shaded rivulet where he’d stashed the bottles on arrival, the wine cool and crisp, fruity and apple-heavy, its texture soft on the palate. Apparently, it was the only Spanish wine worthy of mention, the owner of the winery loyal to the Republican Army. Both Aurelio and Zelda praised the sandwiches, Aurelio devouring a second made for him by his wife, Zelda picking at Scott’s after finishing her own. When the Spaniard fell asleep on the blanket, Maryvonne expressed the desire to take a stroll along the beach and explore the crag, asking if Zelda or Scott cared to join her.

“You go ahead, Scott,” Zelda said. “I’ve seen it and will only want to dive off again.”

“What will you do?”

“Sit in the sun and read my novel.”

So he walked up the white-sanded beach with the taciturn Frenchwoman, feeling Zelda’s eyes on him, fearful lest she get it in her head that he’d planned for any of this.

“You and your wife are lovers still, yes, no, sometimes?” the young woman asked in French. He found the question strange but did not let on. It was only that sometimes, she explained, he and Zelda acted like strangers or newlyweds, not like people who’d known each other a long time. He became winded during the ascent, felt his heart aching, a hollow pain in the center of his chest, and she studied him with a concern steeped in the knowledge of illness.

“Ah, the Caribbean Sea,” she exclaimed, stopping short to take in the view to the south, letting him rest. It was magnificent, she said, the first time ever she had laid eyes on it.

When they started again she lost her footing and he caught her elbow, preventing her from falling.

“You are a man loved by many women,” she said.

He couldn’t figure out why she said it, but he remembered another woman uttering that same phrase—not Zelda, not Sheilah, who was it who’d spoken those very words to him?

“So you and your wife are lovers, yes?”

Again, there was more to the question than the simple if wildly inappropriate interest in how often he had sex with his wife.

“She is everything to me,” he said in clean, pithy French.

“Le monde entier,” she said, repeating his phrase. “But of course, this is never in doubt.” She returned to French for emphasis. “Cela n’a jamais ete en doute.”

Now they were on the tip of the promontory, and as the wind rose and fell he removed his hat. When it was up, the wind whipped her words out to sea, and all he could hear was the flap of her blouse or his jacket lapels. Wisps of his thin hair fell into his eyes, and the young woman flushed above the line of her narrow, elegant jaw, her eyes tearing and bright, the color of the sky itself. He hadn’t realized until that moment that he was attracted to her.

“It is pride,” she was saying, a propos of nothing, referring to Aurelio’s conduct earlier. “The wound is una verguenza,” she continued. “In French the feeling is not so strong as in Spanish. What does English say for this? Dishonor?”

“Shame,” Scott suggested.

“It is also a strong word?”

“It can be pretty strong,” Scott said.

“And what must one do to become free of shame?”

“It is a losing battle,” Scott said.

He looked into her eyes, full of understanding, and believed she was someone he might take into his confidence, as he’d done with any number of women over the past decade, always in intense episodes, in liaisons dependent on drink, charisma, confession. She too would fall for him if he let her, the nurses always did, always trained nurses and actresses. He couldn’t remember why he grouped them, but in his experience women from either profession found his story hard to resist: invalid on the mend, sinner in remission, someone fearless in the face of indignity. With nurses, he supposed, it was that having seen men so often in distress, the facade of manliness crumbling, they were drawn to vulnerability again and again.

As they headed back along the shoreline for the blanket, he worried that Zelda might detect a change in him. He kept watch on his wife in her broad-rimmed straw hat as she pretended to be lost in the pages of a novel, now and then lifting her chin to glance up the beach toward Scott and Maryvonne, whose hand rested on his forearm.

“You were gone a long time,” she said, eyes on the page, too immersed in what she was reading to extricate herself just yet.

“He sleeps the entire time?” Maryvonne asked, eyeing her husband.

“Unless he’s faking,” Zelda said.

“I am awake,” Aurelio said from the blanket, his hat pulled down over his brow and nose so that the brim danced ever so slightly on his lips as he spoke.

“I had no idea,” Zelda proclaimed, springing to her feet, recoiling from the blanket. “Were you awake the whole time?”

It was impossible to gauge how disturbed she was by the idea of his lying there feigning sleep while she read. She drew close to Scott, resting her hand flat against his chest.

“Dearest Dodo,” she whispered to him, “was the walk invigorating?”

“The wind was strong on the promontory, but otherwise it was quite relaxing.”

“She’s good company,” Zelda said softly, gesturing toward the Frenchwoman. “Don’t I choose well? May I borrow her for a few minutes?”

“I didn’t know we were rationing.”

“Don’t be that way,” Zelda said, her breath heavy on his cheek as she hooked Maryvonne by the arm while still addressing Scott. “Do you remember the interview you granted that newspaper in Kentucky oh so many years ago, the first to tag me the original for your flappers, what you told the journalist when he asked you to describe me?”

“That you were charming, the most charming person I’d ever met.”

“It’s true,” she said, brushing a leaf slowly from the front of Maryvonne’s blouse. “That’s what he said, and yet when the journalist asked my husband to continue, when I said go ahead and tell the readers what you really think of me, he wouldn’t say anything else. He couldn’t list any examples of my reputed charms. Imagine that—if somebody’s supposed to be the most charming person in the world, you’d think you could name a few of her charming traits.”

“Not everybody finds the same things are charming,” Maryvonne reasoned. “Perhaps your husband, he finds you charming no matter what you do.”

“Didn’t I tell you we would like her, Scott,” Zelda boasted, turning now to confide in Maryvonne. “Scott is hard and slow to please, but I can see from the way you two were promenading, arms interlinked, that we’ll all soon be fast friends. Let’s you and I walk in a direction no one else has gone.”

By the time Maryvonne and Zelda returned from the walk, something had been decided. Zelda spoke of the day’s itinerary as incomplete. Next she claimed the gelding for herself, announcing that Maryvonne would ride with her, a change in the rotation.

If that’s all there is to the secret, Scott said to himself, I’ll consider myself fortunate.

“The only question is who takes the old nag this time,” Zelda said.

“Stop calling her that, would you?” Scott said, rubbing the nose of the black mare, aware that he sounded annoyed and was in fact annoyed, though not so much about the horse.

“It’s decided, then,” she said, handing the reins of the palomino to Aurelio. “My husband is incurably romantic, always taking the side of the downtrodden.”

Immediately Zelda and Maryvonne rode ahead, prodding the gelding into a full trot.

“Should we chase them?” Aurelio asked.

“They won’t get far.”

“Are you sure?”

“One is never sure with Zelda, which is how she prefers it.”

Most likely Aurelio wanted to see if he could get the palomino to outrun the gelding, but was holding back to be polite.

“I do not know that I have met a woman so daring. She would daunt many soldiers beside which I fight in Spain.”

From time to time the bay gelding would gallop toward them, its triangular head bobbing in perfect syncopation, the small heads of the two women tucked low behind it, Maryvonne peering over Zelda’s shoulder so she too might enjoy the rush of wind, the horse pulling up in a din of snorts and hoofbeats, Zelda looking down at Scott from the taller horse.

“Remember the wisteria in Montgomery? How you said it always reminded you of me wherever you were, also the sycamores and the gothic willows by the river, the one which drooped so low with branches and foliage thick like stage curtains? I suggested we might spend a whole day inside there kissing and doing whatever we wanted and no one would ever find us, but still it was exciting to think they might, if they tried hard enough.”

“I was enchanted,” Scott said.

She rode off and when next she returned she brought up one of her thousand witticisms. Though it was difficult to remember her own words exactly, she could summarize the basic idea. It involved an especially stunning riposte offered to John Peale Bishop or Edmund Wilson.

“I believe that’s already in a story,” he replied.

“Oh, yes, well, I’ll think of others.”

He was still trying to track the first episode of which she spoke. For the life of him he couldn’t remember when it had taken place. It stirred in him a desire to kiss her beneath a willow tree. Most likely she had wished for it to stir in him the desire to kiss her beneath a willow tree.

His wife turned the gelding sharply and Maryvonne yelped involuntarily, but Zelda steadied the horse without event, again heading off down the beach, this time with Aurelio giving chase. Zelda cocked her head over her shoulder, light glancing off her auburn hair as she crouched low to welcome the competition. Scott made a few halfhearted attempts to get the mare to pick up her pace, but she wasn’t in a hurry and neither was he, in all honesty, so he settled for keeping the others in view.

After they disappeared on the horizon, he begin to lose track of time. The beach stretched monotonously before him. His head swayed from too much alcohol and activity, his thoughts heavy like the rhythmic footfalls of the horse, the sand beneath him dizzying as it ran uphill into palms, brush, and timid forest. He let the mare wander down to a dune sprouting grass, and only after she stooped to feed for several minutes did he jerk the reins to lead the horse along the shoreline and enjoy the splash of kickback as she trod through softly rolling peaks of breaking tide.

After a while he came upon a mansion in the Spanish Colonial style so popular in the Caribbean basin, with high white stucco walls and green-tiled roofs, their extended eaves creating shadowed overhangs. The molding above the main floor served as the balustrade of a balcony decorated with symmetrically rounded forms reminiscent of an old mission. It was straight out of the sudden proliferation of architectural styles along the Great Neck waterfront during the 1920s boom, the exact kind of estate in which his Gatsby (if only he were still alive, or real, for that matter) would choose to live. Scott couldn’t remember having passed the building earlier. From Hicacos Point to Club Kawama was more or less a direct line, there was no way to have gone so far astray, and yet somehow he’d done just that.

His head was swimming: how was this possible, goddamnit?

The very thought of pivoting and trekking back in search of his mistake exhausted him. Sweating in the sun, he could feel beads trickling along his chest and belly, his vision bleary. He simmered with low-order rage at Zelda. Why did she always have to turn everything into an adventure? He pulled the reins taut, riding on for several minutes, preparing to turn the mare around and retrace his route, when he caught sight of the palomino underneath a date palm a few hundred yards on, the Frenchwoman alone in the saddle. Why was she on the palomino instead of her spouse? And where were Zelda and the bay gelding?

He dug his heels into the mare’s ribs, pulling up on the reins at the same time, and she neighed and reared, but when he instead slapped the reins on the withers, she fell into a gallop for the first time all day, Scott now sprinting toward the emergency that was always awaiting him, the latest episode in a long history of catastrophes. Maryvonne called to him across the beach and he knew what she would say, that Zelda had been careless and injured herself, that she had wildly attempted to clear a hurdle of some sort and been thrown forward off the gelding as it jumped, crashing to the ground and breaking her neck. Except if that were true, why was Maryvonne unharmed? He tried to fit the pieces together, factoring in Zelda’s talent for soliciting her own ruin. Meanwhile, a Frenchwoman he’d met only yesterday, with whom he’d flirted during a walk on the beach earlier this afternoon, was shouting at him, her voice like orchestral timpani above the percussive trollop of hooves so that at first he couldn’t make the words out. Those sibilant, strung-together sentences sounding like mere babble, until he realized that she was calling to him—“Slow down,” she cried in French. “Scott, slow your horse,” she exclaimed. “No need for urgency, there’s no misfortune here. Zelda is fine.”

Next: Chapter 10.

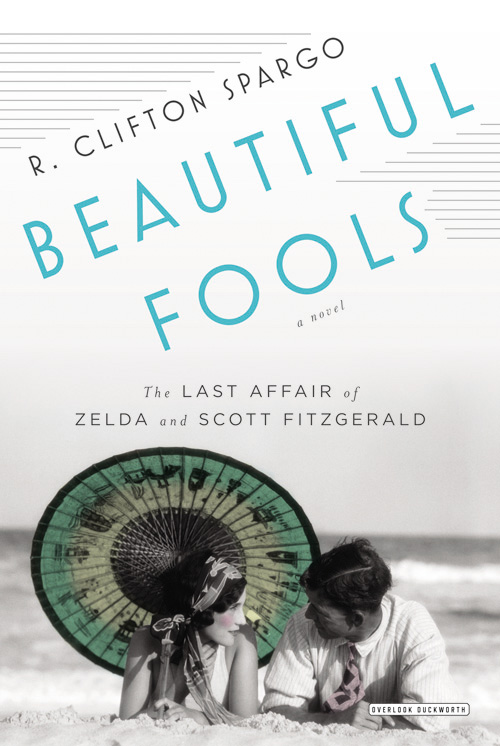

Published as Beautiful Fools: The Last Affair of Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald by R. Clifton Spargo (NY. Overlook Duckworth, 2013).