Beautiful Fools

by R. Clifton Spargo

6

“SCOTT, SCOTT, YOU’RE NOT AWAKE, ARE YOU?” He didn’t answer, but she continued whispering to him, rehearsing a conversation they would need to have sooner rather than later. The days passed so quickly on their holidays. It was Monday already, the weekend having come and gone. She couldn’t let this trip lapse—he still hadn’t said how long they were to stay in Cuba—without addressing the question of whether or not they planned to forge a future together.

“Once I thought, if I went away, I could create myself again—for you, Scott, it was all for you. I could remake myself, never without cost, never without doubts, and I thought, how long will he wait until I am new?” He didn’t stir, but she was restive, wishing to be out on the streets of the Old City, so she swung open the window, inclining into the low balcony wall, the chill of its stone entering her thighs as she let the street noises climb the evening air. Breathing deeply, she dipped into a plie, up and down several times, and then, as if her yearning were at one with the movement, rose on the balls of her feet, pressing her toes into the ground as though en pointe, imitating old habits, wishing she could feel the platform of her Capezio pointe shoes as she leaned out over the balcony, testing her balance, thinking to herself, It would be so easy to fall.

Beneath her, the Calle Obispo was lively with music, chatter, traffic whistles, and impatient horns, with cries of vendors and the squeal and grind of trolleys—the evening’s bustle preparing to give way to the sordidness of night. She could hear someone playing a variation on ragtime, the spangled shimmer of ivory. She withdrew from the window. At the desk, Scott’s sport jacket was folded over the chair, his Florsheim shoes tucked beneath it. He was still so fastidious, she liked that about him. Reaching inside his jacket, she found the journal where she expected to find it, knowing she shouldn’t pull it from the coat or snoop in its pages.

Still she ran her thumb along its spine, resisting temptation, satisfied merely to be touching an object that Scott held daily in his hands, remembering his habit of jotting down ideas day by day, keeping a ledger of characters, dialogue, paragraphs or scenes he’d written, sketches for new plots. A spike of jealousy pierced her, not resentment of the secret contents of the journal per se, but of his arrogant belief in his right to so much secrecy. “I have to trust him,” she chanted under her breath. “If he’s going to come back to me, I have to trust him.” But she couldn’t bring herself to return the journal to his jacket. She remembered a technique of divination taught to her by a psychic she had visited in Asheville. First, you stood a book of sacred import, say, the Bible or the Koran, upright on its spine on a desk or flat surface. It was hard getting the soft leather binding of the Moleskine to stand upright, it wouldn’t balance on its own, so she placed a finger atop the spine. She heard the raspy hum of snoring behind her, Scott murmuring and stirring in the bed, but when she turned to check on him he rolled onto his side to stop himself from making the noise that was interrupting his sleep.

How did the technique work again? You let the book fall forward, the pages splaying on the surface of the desk, as you slid your finger beneath the folded-open book with eyes shut and then flipped it, running your hands over the surface of the page as if reading braille until your index finger stopped. That’s all she would read, nothing else, no matter how awful or mysterious those few words might prove to be. Just the sentence on which her finger came to rest, enough also of the surrounding passage to make sense of it. Then she would close the journal and become his obedient wife, respecting those sacrosanct boundaries he was always so worried about. She let the journal fall onto the desktop, inserting her finger into the tented space beneath the binding to turn it right-side up, eyes still shut, gliding her hand along the provident page. When her finger paused, she worried she was on the wrong passage, so inched it downward, but then, not wanting to second-guess herself, slid it up to the original location. After a few seconds she opened her eyes. Reconstituted. Her finger had come to rest on that word. She read from the beginning of the sentence: To go back to her and be reconstituted—that was what he wanted today as on so many previous days, the wanting of it like a nagging injury, a hole at the center of his being. After a few drinks he was able to make the desire subside, grateful for the dulling of memory, but always he could recall, even after the sensation itself was gone, what it felt like to want her again.

“Where are you?” Scott asked from the bed.

Those few words from his journal could only refer to her, maybe some fictive version of her, but they were about her nevertheless. She must not let Scott see what she had been doing. Quietly she folded shut the journal, dangling it behind her over the desk, craning her neck toward him.

“I’ve given myself a chill,” she said. “I woke up a while ago and stood too long by the window in the evening air. So I came over here to put your coat on, you don’t mind, it smells like you and I like the feeling of being wrapped in you.”

She lifted the jacket onto her shoulders, arms crossed over her chest as she tugged at the lapels from inside, then reached a hand beneath to stash the Moleskine in the inner pocket. The jacket really did smell like Scott as she poked her nose inside the collar, detecting the traces of Bay Rum, also the spicy scent of cinnamon, chocolate, and cigarettes, and an earthy odor she associated with the back of his head. She heard rustling and when she lifted her chin again he had tossed off the sheets, thrown his lanky white legs to the floor, pausing to catch his breath.

“Are you all right?” she asked. He did not appear to be rested from the nap, the side of his face ruddy, irritated from the pillow.

“You’re probably hungry by now,” he said.

“How did you guess? Am I always so hungry when we travel? I really can’t remember, but it seems to me it’s been a long time since I had such an appetite.”

“Only when you’re happy,” he started to say.

“I suppose it’s because I’m happy,” she said, answering her own question, laughing at the happy coincidence of their words, then splashing onto the bed beside him, soon caressing the high tense muscles of his neck and running fingers through the mossy thin hair at the back of his head. Even as her fingers combed the hair, she was thinking two opposite things at once: He is a stranger, his life is full of strangers, and, I know this person better than anyone in the world.

“When I’m miserable,” she said aloud, “I never want to eat at all. You remember how pinched and cadaverous I was only three or was it five years ago in New York when I had to stay at the, what was the name of that institution, oh, let’s not dwell on such things. Right now all I am is happy—for the two of us, for our days in Cuba, for this time out of time.”

“And, doubtless, you’ll appropriate my dinner again,” he said.

“Not if you’re going to be so ornery about it, memorizing and then listing all my trespasses,” she said. “Although I can’t see how it matters, since you hardly ever finish your meals. It’s my duty to eat for both of us.”

“Well, maybe if I had half a ch, ch—,” he started to say, breaking off in laughter that dissolved into a fit of coughing, in which she could hear the customary wheezing of the disease tunneling deeper into his lungs, the hollow barking of his badly bruised brachia.

“I don’t like the sound of that cough,” she said. “Are you sure you’re taking care of yourself in California?”

“It’s nothing,” he said. “I’ve beaten worse. You should know better than anybody the wonder of my recuperative powers. I’ll rest up and be better in no time.”

“Yes, and I’ll make sure you eat something more than chocolate for dinner tonight. Of course, you won’t be able to keep up with me, but can you imagine how much I might eat if we ever again have a run of good luck—I might become as big as one of those Goya women.”

Outside the hotel she took his arm and he walked to her left, stepping now and then off the narrow sidewalks into the street thick with pedestrians, cars, and horse-drawn carriages, sheltering her from its dirt, exhaust, manure, smears of discarded food, all the refuse from a day on Calle Obispo. The foot traffic parted only for street trolleys, their bells angrily clanking as they rattled along tracks that protruded abruptly from the street, the drivers slowing but never fully stopping to release passengers or take on new ones. In the wake of the trolleys, the automobiles would make a run of half a block, swerving around potholes only to bog down again among the people crossing indiscriminately from one narrow walk to the other. Repeatedly a bright red Packard raced ahead of them, and then slowly they reeled it in.

“Tonight is too early,” she whispered, keeping herself from leaping ahead, from plunging straight into years of pent-up desire.

Wading through the crowds that funneled in either direction down the narrow street, she stepped up onto the sidewalk, then down into the street, careful not to snag her heel on the broken, crumbling curb, her wide-heeled shoes catching on an exposed iron rod, but Scott was there to prevent her stumble. Vendors tried to draw them into shops whose bright window displays featured flowers, fine dresses, shoes, and everywhere the colorful banners of the lottery, the numbers in bold display. “Americans, come here, please,” the shopkeepers called, walking alongside Scott, wares in hand. Again she and Scott caught up to the red Packard and she stared down at the well-dressed passengers, immersed in pleasant conversation, unfazed by their sluggish pace.

Out of nowhere a girl with bare feet, sporting streaks of dirt on her nose and jaw and a soiled beige jumper, appeared at Zelda’s side. Uttering words in Spanish that Zelda could not understand, the girl petitioned the senora, taking hold of her wrist with softly supplicating words. “Bonita mujer Americana,” she said and inserted her small, soft, clammy palm into Zelda’s, directing her attention across the street, but at what it was impossible to say.

“What is she saying, Scott?” Zelda asked, smiling at the child, flattered but also rendered uneasy by her pleas. “I think she wants us to follow her. Do you suppose something’s wrong?” The girl tugged at Zelda’s arm with ever-greater urgency.

“Zelda, we have to be at the Floridita in a few minutes.”

This was the first she’d heard about a schedule, and it annoyed her that Scott hadn’t said anything until now. She had a right to be kept apprised of their plans.

“Well, what do you want me to do?”

“Let go of her hand.”

“Give her some money, Scott. I’m sure that’s all she wants.”

He started to take out his billfold, peeling off a five-dollar bill, but the little girl waved her head from side to side, motioning with her free hand for Zelda to follow her, saying, “No, no, de esta manera no, por favor; me siguen,” jerking almost violently at Zelda’s arm now that she detected reluctance.

Angling across Calle Obispo, led by the girl, they headed down a side street and Zelda, briefly overwhelmed by the rotting-eggs stench of sewage from nearby drains, felt queasy as a woman with an infant in her arms greeted them. Even before the woman spoke, it was clear what she would say. Indicating the infant bundled against her chest, holding out an empty palm, she informed them that she was without food for her family.

“No tengo comida para el bebe,” she said, repeating herself several times. “El bebe,” she said, extending the child in her arms, as if the wants of an emaciated child need never be translated. She scraped together enough English to say, “You come, please.”

“Zelda, we have to be going,” Scott said without resolve, and she looked at him with helplessness, shrugging her shoulders, tipping her head sideways to indicate the girl still clamped to her wrist. At a store doubling as grocer and pharmacy, they approached a window that opened onto the street, where a slight, round-faced Chinese man had already prepared a sack of groceries for the woman.

“You pay money, yes,” the woman announced. The man behind the counter passed the sack to the woman, then looked up at Scott, naming a price in excess of what he expected.

Money matters made him irritable. He could recall years when he’d thought nothing of throwing ten-dollar bills at waifs, friends, strangers met in a bar, the doormen at the Waldorf or the Algonquin, Zelda all but indifferent to how they squandered money as long as enough of it was spent on her. It was her simple belief that he would always provide more. Even now she couldn’t understand that the sum he was giving away, if doubled just twice, might make the difference between seven days in Cuba and five.

“Zelda,” he said, forking over the money to the clerk, hearing the sharp treble of the Western United States creep into his rebuke, as the woman with the infant in her arms and her beggar child at her side waved goodbye, retreating down a narrow lane on which the yellow, pink, and green buildings so closely fronted the sidewalks that the awnings and white iron balconies above seemed to form an arbor here in the middle of the city.

“We can’t afford,” he said carefully, “to pay for the upkeep of every waif we encounter.”

Back on Calle Obispo he checked his watch, wondering how Cubans interpreted late arrivals, whether they took them for granted much as the Spaniards did. La Floridita came into view, the building framed in gold frieze and folding around the corner of Obispo and Bernaza, its shuttered doors thrown open so that the street and restaurant were continuous, some of the patrons standing above friends seated at dark wood tables whose bowing legs crawled crablike onto the sidewalks, the actual entry to the club seeming a mere formality. Scott led them under an awning, where a host greeted them, inquiring if they were here for drinks or dinner. “We’re meeting Mr. Mateo Cardona,” Scott said, and the host waved him through, saying, “Of course.” Beyond a refrigerated seafood display case emanating cold air and the ocean-heavy scent of mackerel, shrimp, stone crabs, and lobster, he guided Zelda to an open spot along the bar, where a bartender measured rum and maraschino liqueur in arcing plashes into a silver-plated shaker, adding shaved ice, then tossing the concoction, before pouring the drink into long-necked martini glasses.

“Two of those,” Scott said in clumsy Spanish.

“How did you know about this place?” she asked. It was reminiscent of cafes they used to visit along the Riviera before it was overrun by Americans.

“Senor Cardona is meeting us here,” he said.

Scott didn’t mention that he’d also heard Ernest speak of La Floridita last year in California, nor that Max had reminded him by cable that, whether or not he looked Ernest up, he ought to try the daiquiris there. Nothing complicated about Max’s motives, and though Scott wasn’t altogether against a rapprochement with his old friend, he knew the fates were set against it. It was never just the two of them in a room anymore—all the history of unwanted advice tossed back and forth, the omnivorous ego of Ernest to be grappled with, and of course the dreadful combination of Scott’s failures and Ernest’s constant climb.

The bartender slid the daiquiris along the bar, and Scott peeled off a few bills from his roll of pesos. Drinks were cheap, at least someone in this country wasn’t gouging him. He looked around the bar. Mateo was nowhere in sight, which meant they weren’t late, which meant Scott could relax, enjoy his drink, and feel the knot inside his stomach release.

***

So far it had been one of those days squandered on trivialities: a fruitless follow-up to yesterday’s visit with the detective succeeded by an errand to the bank, a dispute over the sum in his account, then the hassle of wiring payment to a lawyer in New York City for paperwork he was executing on behalf of an American investor (the lawyer kept billing him for additional petty costs). His reporter friend from the Havana Post was to arrive shortly after the siesta hours, no specified time, but it was growing late. Annoyed by the fact that he still hadn’t received a reply on his query to the chief of police, Mateo kept busy in the meantime. Displacing papers on his desk, he moved items from one stack to another while drafting a list of potential investors in a new casino near the Hotel Nacional, a list filled with local citizens but also Europeans and Americans who were regular or part-time residents of Havana. Appetite began to kick in and he decided the reporter wasn’t coming. He snatched his sport coat from a rack by the door, preparing to set out for La Floridita early, when he heard the buzzer. Pulling on his white linen jacket, he met the reporter outside, remarking, “Almost left without you,” before leading him along San Pedro, the noisome harbor to their right, ships running in and out at this time of day, belching smoke, releasing the flatulence of burnt oil and gas from their engines, horns blaring so that the skiffs and smaller boats would steer clear.

“Did you know the wife went crazy a decade ago?” the reporter asked.

“Mrs. Zelda Fitzgerald, are you sure?” Mateo asked. Scott hadn’t mentioned anything about mental illness, but of course one wouldn’t talk about such matters, not even with close friends, never mind new acquaintances. “In what way?”

“Not many details, I got it off the wire from a colleague at the New York Evening Post,” the reporter said, preening for Mateo, trying to come off as more important than he was.

“But you are too canny to have learned nothing.”

“My colleague tells me Scott has disappeared into Hollywood, never publishes anything of note, while she spends most of her time in asylums.”

“None of which you would mention, I hope,” Mateo said.

“No, my angle is that they were the most glamorous couple of New York in the twenties, also in Paris for a while, he a front-page writer for the Saturday Evening Post, his wife the celebrated flapper. I’d like to find out what they’re doing in Cuba, if he’s researching a script for Hollywood, that kind of thing.”

If the story came out and it brought the Fitzgeralds unwanted attention, they might flee the country before Mateo had secured Scott’s trust, and he wanted to make sure that didn’t happen. So as he entered the cafe at Hotel Santa Isabel, Mateo reminded the reporter that he was to be his guest.

“What is of passing interest in the Old City this week?” he asked the reporter after a first drink. He didn’t quite trust the reporter—after all, gossip was just that, something whispered, not worth saying aloud. He rather hated the society pages of newspapers, having been featured there himself one too many times, his name popping up in association with various women found on his arm, sometimes winning him a note of reproof from his otherwise noncommunicative mother in Santiago.

“It is a service, like any other,” said the reporter, who like many a soft journalist before him still harbored serious ambitions. He had started working for the Post’s “Activities in the Social World” page three years ago on the rationale that it might open doors. It was hard for him to accept the fact that his secondary status in life appeared to be a permanent track. Keeping company with Mateo was one of his tricks for maintaining a high opinion of himself.

“You offer the public a view from the ground, without filter, the rumors of the street,” Mateo said, indulging his old associate. “What is the latest covert political news?”

“So you recall that I was among the first to track Falangist activities in our country?”

The two men ordered a second round of mojitos as the waiter brought a plate of prawns.

“Months ago when it became clear Franco must win, did I not say that Antonio Avendano and Alfonso Serrano Vilarino would begin to feel confident in their cause?” The men he mentioned were closely monitored proponents of Franco’s Falangist alliance, who sought a Fascistic solution to Havana’s notoriously unstable politics.

“And you were not wrong,” Mateo said, his voice hushed. His friend the gossip columnist was far too brash and boastful to make a good journalist.

“I did much research, you know,” the reporter said, heaving the ignominy of neglect into his chest. “Collier’s was to run all that I found as a feature article, but instead turned the information over to the FBI of the Americans.”

“A tough break,” Mateo conceded. “But your information tightened international security, and these men you talk of, what do they matter now?”

The reporter still believed the article in question would have made his name, and the memory of it stirred bitterness in him. Mateo had served as a source for the story. Since the Cardonas were among those old families that put their faith in the Church as a beacon for national life, he fed his associate tidbits about where one might find Fascist sympathizers in Havana, among, for example, the staunchest of Fulgencio Batista’s supporters, all on the tacit condition that the reporter would point the finger away from the Cardonas—away from, for instance, his beloved brother, Hector, celebrated in some circles, maligned in others, for spending the past two years in the mountains north and west of Barcelona among the Falangists as they advanced on that great city. It wasn’t just family Mateo protected, though. He did business with proto-Fascists, several of whom he gladly named for the reporter, others whose identities he labored to conceal, even though the ones he kept secret leaned just as eagerly toward Fascism as the others—all of them encouraging Batista to take his cues from Franco and to protect Cuba’s Hispanic heritage, and bask in the Church’s guiding light, and curtail American influences. To this day Mateo was divided in his opinion about whether Cuba’s interests and those of the United States coincided, and for that reason could not entirely endorse his associate’s rabidly anti-Fascist views. Officially Cuba would side with the Americans in the war to come, this was only proper, but still he remained ambivalent about how much advance work Cubans ought to do for their neighbors to the north.

“In this very hotel,” the reporter said, “there are Germans who should not be here.”

“Let the authorities follow the leads, you did what you could,” Mateo said, checking his watch, pulling his seat back from the table. “Please, the bill is paid, finish your meal, though I must be off. And on that other matter we discussed, you will give me a few days.”

“Sure, why not,” the reporter said magnanimously. “Let us give Mr. and Mrs. Fitzgerald their privacy for now, let them enjoy our great city. It is hardly breaking news, but you will help me get the interview with them, and will not let them slip away?”

“Not a chance,” Mateo said.

***

Zelda poked him in the ribs, her head listing to the side, until he too turned to peer down the bar where a row of women dressed in garish clothing leaned against it at the far end.

“It’s nothing we haven’t seen before,” he said, keeping his eyes below the gaze of the prostitutes to avoid misunderstandings.

“That’s not what I mean,” she said. “Look at the one third from the end.”

He lifted his eyes to the mirror at the back of the bar, and when he saw that the woman in question was waving at them, he immediately said, “Zelda, please don’t overreact.”

“What was her name?”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“He presented her as his girl, didn’t he?”

“I can’t remember. What difference does it make?”

“You really think it makes no difference?” she asked. “You take me out on the town with such a woman, and it’s not supposed to bother me? What did you think would happen?”

“She had nothing to do with what happened.”

“What about the knife, I forgot all about the knife until now, what about the knife she pulled on me?”

Scott reached into his coat, trying to remember something he’d written in his journal Saturday night after they returned to the hotel, but the Moleskine wasn’t in the pocket above his heart where he kept it. He felt down along the side of the jacket. Nothing there either. Panic swept over him as Zelda clamored for attention and he reached his hands to his chest, patting himself down, two hands at once, discovering a square bulge in the other breast pocket, the wrong one, but at least the journal wasn’t lost. As he reached for it, however, he could no longer remember what it was he’d wanted to check.

The girl from Saturday night beckoned for them to join her.

“Now we must say hello, Scott,” Zelda said.

“This is neither the time nor place for renewing acquaintances of that sort, Mrs. Fitzgerald,” a man said, intercepting them.

It was, of course, Mateo Cardona, who uttered his command while firmly gripping Scott’s shoulder, then bowed forward to graze Zelda’s cheek with a kiss.

“We were only going to say hello,” Zelda protested. “She was good enough to be on your arm last night.”

“Our table seems to be ready,” Mateo said, offering no further explanation, refusing even to glance at the girl as they passed within a foot of her at the bar. Another man was seated at their table and he now stood to pull out a chair for Zelda.

“May I present General Ernesto Menendez,” Mateo said, obviously expecting his friends to intuit the honor of being in the presence of such a man. He explained briefly that the general was a hero of Cuba’s war for independence.

“The Spanish-American War?” asked Scott, his curiosity piqued, since he had long been a student of military history. “Which battles, if you don’t mind my asking?”

“That is your name for the war for Cuba libre,” the general said. “For you Americanos, a Spanish-American war includes all battles to be rid of the Spanish presence in the Americas, while collecting as much of the leftovers for yourselves as is possible.”

Scott questioned the general’s interpretation of history, saying he had always understood his nation’s intentions in Cuba to coincide with the course of self-determination on which the country continued to this day. He mentioned Teddy Roosevelt and the Rough Riders, the Battle of San Juan Hill, the sinking of the Maine.

“Perhaps it is not so simple as that,” the general replied amicably. Still, he had met Roosevelt; he had friends from the United States who fought among the Brigadas Internacionales in Spain, in defense of democracy, in the effort to prevent Spain from falling into the wrong hands.

“Only now it has fallen,” Scott said.

The general was immaculately dressed, in cream-colored jacket and pants, the jacket with a double-breasted lapel, the tapered trousers drawing a fine line toward his tan loafers. His neatly cropped white hair set off a square face, his skin fair, though of a pearl rather than pinkish hue. An old friend of the Cardona family, he was on display, maybe only so that Mateo might impress upon his guests that he was not a misfit among his own people.

“My friend, however, is a diplomat always,” the general said to Scott, who hadn’t been paying close attention. “I am no companero of the Communists, but they rally to our cause, it seems to me.”

Zelda had missed a piece of the conversation and asked Scott whether it was important. Was the general giving his views on the war in Spain?

“What war? It is over. What hope to defend democracy if the great democracies will not defend her? In your opinion,” the old general said, again facing Scott, trying to mask his disgust, “should not the United States intervene? Was this not a war for them?”

It was, Scott assured him. Unfortunately, not all saw it that way.

“Unfortunately.”

Scott was tempted to mention his friend Ernest Hemingway and his work on the film The Spanish Earth, a piece of propaganda for the Republicans, also the screening of the film at a fund-raiser Scott had attended only last year in California. He might have named others among his circle who had taken up arms or pens in defense of Spain. He was tempted to expound on his own hatred of the Fascists, but thoughts of war in Europe made him recall his time as an enlisted man during World War I, when he had failed to cross the Atlantic; and under the sway of neglectful history, he suffered once more pangs of irrelevance.

Zelda was asking Mateo about the man from last night, and Scott could hear him saying, “Most likely he will recover, so please do not concern yourself, Mrs. Fitzgerald.”

All seated at the table had spent time along the Cote d’Azur in France, enchanted by the white splendor of its beaches and the translucent Mediterranean waters. Charting their travels as a couple, Zelda spoke cheerfully of Antibes, of the villa at St. Raphael, of trips to Monte Carlo—all of this, she asked them to remember, before anyone had discovered summers along the coast. She took long swims in the sea and danced at the beachside bistros, she relished the private salons in the casino at Monte Carlo, asking Scott to corroborate her memory on this point or that. It was as though she now recited pages from her 1924 affair while omitting mention of the French flyboy with whom she’d fallen in love, recalling the year in which she betrayed her husband as a time of complete unity between them—and yet she meant every word of it. Scott could see no reason to steal that year back from her when there were so many since with which her imagination could do so little.

At one point the general took Scott aside to say that Mateo had mentioned his interest in investing in one of Havana’s new hotels or casinos.

“Your friend must have misunderstood the state of my fortunes,” Scott said with a laugh.

“You’re very thoughtful about your finances,” the general said. “This is exactly what I myself look for in an investor.”

So the general and Mateo were in business together. It annoyed Scott to have been dragged to this bar under false pretenses.

“This is why I recommend, my friend, that we present some options to you,” the general said.

Scott had respect for the man’s elegance, for the nonchalance of his sales pitch. It was beneath his dignity to become importunate or pushy. The matters of which he spoke were affairs among gentlemen.

Assured of the general’s good will, and reaffirmed in his confidence in Mateo by the company he kept, Scott began regaling the two men with stories, told with deadpan panache, about the exploits of Zelda and Scott as a foolhardy young couple. He told them about being photographed running through a fountain outside the Plaza Hotel.

“What was the point of your actions?” the general asked.

“But that’s just it,” Zelda jumped in. “There wasn’t any. Why not just be glad that you were beautiful and oh so young and able to drink for several days, dance every night, even in fountains, or go for a swim in the Hudson River in your finest clothes.”

Mateo seconded their careless view of life in the twenties in New York City, and also in Paris, which he had visited only once, and though the general was a man inclined to order, he was a drinker who believed in catharsis, as he put it, as long as it was not a perpetual state of existence.

Testing the old man’s tolerance, Scott told him about the time he had passed out behind the wheel of an automobile on their way home from a soiree in the French Alps, Zelda in the passenger seat, the car stalled at the edge of a precipice, the two of them sleeping off the glimmering daze of several consecutive nights of revelry, unaware that for hours on end they were no more than two feet from rolling into a gorge.

“In the night I got up to relieve myself,” Scott said, “and I found a bush of some sort, most likely some thistle running along the precipice, and somehow I returned to the car without stumbling over the edge, apparently without ever noticing where I was.”

“Like a man who sleepwalks in a minefield,” the general said.

“It was not until morning,” Zelda remarked, “when I awoke and opened my door to find that if I took one small step at a time, pas de bourree as they say in ballet, I might patter tiptoed back up the ledge, alongside the car, walking uphill—”

“Couru, couru,” the general said, showing himself to be an aficionado of her forsaken art.

“But if I took merely two graceless forward steps, like any crude pedestrian, I would have plummeted to my death. Only then did we back that beaten-up jalopy off the precipice.”

“That’s magnificent,” Mateo said.

“It was a fine sports car,” Scott said, “a coupe of some sort. Zelda has no memory for such things.”

“I thought we were just telling tall tales,” she said. “What do the details matter?”

“And they are mostly true, yes?” Mateo interjected.

“Fair enough,” Scott said. “I have always enjoyed my wife’s flair for adding color to our history.” They both knew he might speak of the time she grabbed the wheel and attempted to steer them over the edge of a cliff, but he wouldn’t say such things, not unless prompted by her jealous, impassioned denunciations of him, not until years of pain and alcohol and remorse were again all at once coursing through his system.

“In the real story,” he said, “but honestly I can’t remember, didn’t the French police come and wake us up and warn us how close we were to the cliff?”

“It’s more exciting the way I tell it,” she said, turning again to their hosts. “Isn’t it, gentlemen?”

“For all my action in the field, I have been so close to death few times in my life,” the general said. “Your adventures, Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, are battles in their own right.”

The waiter brought another round of daiquiris and Scott took a swig of his drink. He no longer felt defeated by the misadventures of this past year, or by the follies of his youth, but somehow better for them. He asked if his Cuban hosts wanted to know what making movies was like, what it was really like, and the two men responded, “Hear, hear,” and he could tell they found Hollywood far more interesting than the life of an ordinary author, even one who had formerly dominated the pages of the Saturday Evening Post. He excused himself to use the bathroom and as he passed the bar, lips set in a neutral if friendly smile, he stared down the row of prostitutes and observed with some relief that Yonaidys was no longer among them.

“Do you know big-name stars?” Mateo asked as he returned to the table.

“So many,” Zelda said, bragging for him.

“Not so many,” he said, “but more than a few.”

“Oh, do tell them about Joan Crawford,” she said, pleased that they were taking pleasure in each other’s company, in shared history, in stories of his life and hers volleyed back and forth. “Tell them about her marvelous weakness. Someday my husband must write an expose, he is so satiric and gentle and yet full of terrifying insights about the superlative egos of the glamorous. You would read such a book, wouldn’t you, Mr. Cardona?”

“If written by Mr. Fitzgerald, why, of course.”

“Will you tell us the story, Scott?” Zelda said, trying to get a read on him, begging ever so sweetly. He was flattered by her flirtations, no matter how transparent.

“I begin with the sad part,” Scott said. “It is about a wonderful film I wrote for Joan Crawford that has been put on hold, as so many great projects in Hollywood are. It was perhaps a little too spicy for the censors, since it featured a story of adultery in which the sinners don’t end up groveling for mercy from the gods. Of course, everybody knew the risk going in, it would have been groundbreaking, the celluloid Madame Bovary, an honest, hard-hitting look at passion and betrayal and their consequences without easy moralizing. Just people as they really are, suffering for their mistakes, not all that regretful about them. No one was more eager for the story than Joan herself.”

“Well, after all,” Zelda said, “you might have been writing her biography. First, that horrible, abusive marriage the papers paid so much attention to, then the affair with Clark Gable, so steamy and notorious the studios had to put a stop to it.”

“When she heard I was to write the script,” Scott said, “she approached me at a party and said, ‘Write hard, Mr. Fitzgerald, write hard.’ I told her writing is always hard, but I would exert all my talent and time and energy to produce a script she could be proud of. She was convinced, of course, that the very idea of writing for her ought to be enough to make me write well.”

“I should think so,” said the general.

“And why do you think this?” Scott asked. “Because she is such a special talent?”

“Well, a great beauty certainly,” the general said. “Do not all Americans revere their Joan Crawford? I have it on authority from my nephew who fights for liberty in Spain that a band of yanquis quarrel many weeks for the right to name their battalion after Joan Crawford, the marvelous actress whom they all revere, but it was not allowed. She is a very good actress also, I think, no?”

Zelda began to laugh, anticipating the punch line of a story she knew in all its versions, relishing any anecdote about the vapid personalities of Hollywood.

“Well, no, not exactly,” Scott said. “I’ll speak in candor if all present swear a pact not to pass my story on. It’s not the best of strategies for obtaining work in Hollywood to run down the stars you write for. So do I have your word, gentlemen, lady?”

“Of course,” Mateo’s friend said.

“Swear,” Scott said.

“I swear, I swear,” Zelda chimed.

But Mateo hesitated. “I am insulted that you ask me such a thing.” Alluding to the events of the weekend, he added, “I am a model of discretion. Is this not clear by now?”

“Never in question,” Scott said, reaching for the Cuban’s forearm, feeling in his element, master of the situation. “It was a mere formality, a pact to illustrate my point. I don’t share these stories with just anyone.”

Mateo acknowledged the gesture, extending his hand over Scott’s, clasping the knuckles, then releasing them to say, “Now you must continue. You were about to tell us that Joan Crawford, named by LIFE magazine as queen of the movies, is less than talented.”

“Well, as your friend and mine reminds us,” Scott said, pausing, nodding respectfully at the general, “she is beautiful, but as for talent—”

“Oh, never mind about her beauty,” Zelda interrupted. “I’m not entirely sure why bug eyes have become all the rage.”

“Because of Joan Crawford,” the general said with sincere detachment.

In the late twenties while Joan Crawford’s star was on the rise and Scott still the voice of the Jazz Age, he had declared her in an interview the supreme flapper, smartly dressed, dancing at clubs until the daylight hours, eyes larger than life, larger even than the fast life she was taking in all at once; and the remark stung Zelda. It was during the years of their long falling off that he came to see how cruel it was to have said what he said. To strip Zelda of her title as the quintessential flapper, a title he bestowed on her but she had procured by rights as model for all those brave, reckless, winning heroines he wrote of. To take what was Zelda’s and give it away to a Hollywood actress—that ranked high among his crimes against her.

“Well, fair enough,” Scott said, raising his glass. “To Joan Crawford, the champion of the stunned, wondrous, eye-popping gaze. Let me tell you something, though. She is interpersonally charming, charismatic, and some of that quality is what translates onto the screen, but I find her beauty forced.” He did not look at his wife, but he was certain she delighted in what he was saying. “Never mind, though, because we were talking about talent. So when I realized Joan was to star in the film I was writing, I made a study of her past performances, watching her in almost everything, asking the studio to screen them for me day after day, films such as Possessed, Grand Hotel, Chained, Forsaking All Others.”

“Fine work if you can get it,” the general said. “I would not be sorry to be paid to watch Joan Crawford movies.”

“Writing for the movies is hard work,” Scott replied. “It’s good to know whether an actress can carry off the lines you write for her. So I studied Joan’s films and soon realized that she has one glaring weakness. She can’t change emotion mid-scene. In every movie, every scene, she’s all one thing, then she’s altogether something else. No in-between. No gradations. Ask her to change emotion over the course of a scene, ask her to shift gears, and she freezes, strains, puts a hand up to her face like a mime and runs it down from forehead to chin so as to wipe away the old expression and put on a new one.”

“Oh, she struggles so sincerely as she moves from sadness to mirth to wrath,” Zelda joined in, “that it’s impossible not to overhear her thinking, ‘Now I’m supposed to be blase’ and ‘Now I’m supposed to be stunned by terror.’”

“Or she turns her face from the camera, on the supposition that the present emotion is too much for her,” Scott said, smirking as the picture became clearer in his mind, “and she looks up and there’s the new expression, she found it somewhere down by her shoes.”

“Surely you exaggerate,” Mateo said.

“Possibly,” Scott replied. “But go back and watch her films sometime and you’ll start to see what I mean. Of course, directors and cameramen have all kinds of tricks to distract you, moving another actor into the foreground, panning the camera away for a few seconds, but if Joan has to carry the scene on her own, and there are two emotions to be enacted in relatively short order, well, all I’m saying is, in that scenario, I’ll take the mime.”

“So what good does it do for a writer to know such things about an actress?” the general asked. “I would think you would find it paralyzing. What am I to do with such limits?”

“That’s quite perceptive of you, General,” Scott said. “But in reality a writer can help out a director quite a bit if he understands the actor’s strengths and limits. Use minor characters to push her through transitions. Make sure much of the emotion occurs—as Aristotle recommended one should always do with violence—offstage. The strength of film as a medium is sometimes also its weakness. We want to read everything on the character’s face, but just as in real life, there are so many ways to see a face and not see what is happening there.”

Next: Chapter 7.

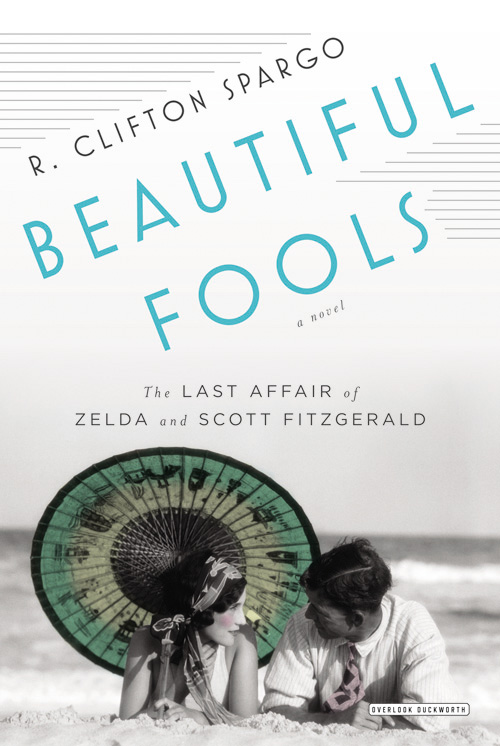

Published as Beautiful Fools: The Last Affair of Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald by R. Clifton Spargo (NY. Overlook Duckworth, 2013).