The Disenchanted

by Budd Schulberg

7

The eyes and ears of Victor Milgrim, it seemed, were in the corridors, the office walls, behind the couches; sometimes the studio itself seemed to be merely an architectural extension of his being. And so, when Peggy’s call brought the unexpected information that Victor Milgrim was ready for their conference, Shep wondered if this was the Great Man’s way of pointing a finger at Halliday’s two-hour lunch on the other side of town. That it could be only coincidence that timed Milgrim’s call before Halliday had returned from the Vendome did not even occur to Shep. So saturated with the insistent spirit of Victor Milgrim had this atmosphere become that Shep automatically accepted his call as a rebuke aimed at Halliday’s dilatory lunching.

“Peggy, we—can’t come right down. Mr. Halliday is—down the hall.” In desperation Shep grasped the first euphemistic straw.

“Well, soon as he comes back, get your derrieres down here. The conference on now is breaking up and you’re next, my sweet.”

Shep was too concerned with Halliday’s absence to hold up his end of the repartee. Now there was Halliday to worry about. It was 3:05. What if he had quit? Decided life was too short and this stint too gruesome? Could be. A man of Halliday’s sensibilities … That was it. He had talked it over with his agent at lunch (perhaps some day Shep would rate a top agent like Harper) and decided this ball of damp fluff was not for him. Shep went a little numb with disappointment. He had started so high that morning, borne up in a rush of excitement at the chance to work with Halliday. He had even believed—or was he just kidding himself—a certain tentative bond possible between them.

Halliday came in with soft reluctance. He bowed slightly, with a kind of sarcasm Shep could hardly resent, since it clearly included them both. “Mr. Stearns.”

“His Master’s Voice calls us,” Shep said. The note of badinage was intended to hide his own apprehension.

“Oh, Victor’s bothering us already?”

(Damn it, why did he have to play the Great Writer for this boy?) He wished he could feel as aloof as he had made himself sound. He mustn’t truckle to Victor Milgrim. What was Mil-grim, after all, but a dandy with a flair for success ?

But intellectual snobbishness would not exorcise the fear. At least in his old age—he made this jest so often it was coming true—he had become an interchangeable part of the machine. Well, only for a little while, ten weeks—what’s ten weeks in a lifetime?—he would play the fool to King Victor. Only he would maintain the fool’s delicate line of insubordination.

“I guess he’s waiting for us, Mr. Halliday. Seems to want a story conference.”

“I can never think in a story conference,” Halliday said. “It’s too—too public.”

“I know a writer who can’t write at all,” Shep assured him. “But he’s a genius when he’s talking on his feet.”

As they were going out the door the phone began again. “It’s Mr. Milgrim,” Halliday’s secretary said, caught in the web of panic like the rest.

“Tell him—tell him the hook-and-ladder boys have already started sliding down the pole.”

But by the time they reached the office, Peggy said (somewhat more formally than if Shep had been alone, in deference to Mr. Halliday’s apparent reputation): “It will be just a few minutes. Bill Ross” (that was Milgrim’s assistant) “and Blumberg and Marsden” (the writing team scripting Pursued) “just sneaked in for a minute.”

Twenty minutes passed slowly. Peggy was inside with her shorthand book. It was the waiting, Shep thought, the waiting. Eventually this waiting sawed you off at the base of your self-respect.

As the minute hand crept on, Halliday’s spirits drooped. On his arrival the door should have been flung wide, the carpet unrolled. The nerve of vanity in him was hopelessly exposed.

Shep Stearns, increasingly responsive to Halliday’s susceptibilities, but younger and tougher and less reasonable, hated the idea of Milgrim keeping Halliday waiting. For him, whose thinking ran consistently to the grand abstractions, it was a symbol of the injustices at loose in the world.

Now the nearest door was opening, releasing the unhappy sounds of obsequious laughter. Julie Blumberg, a sensitive, talented kid when he had come out eight years before, was talented and successful and cautious now, his aesthetic principles sublimated to the welfare of his family. Lex Marsden was a shrewd man who played golf and cards with the producers and knew the plot of every successful picture turned out in the past ten years. He was useful to Blumberg, who still had to make up in talent what he lacked in push. They had just had a bad time in the conference; Milgrim had thrown out their new line; they’d have to come up with something, but fast. Bill Ross, who had been enthusiastic about their line but had failed to defend it in this conference when he saw which way Victor Milgrim was blowing, Bill Ross whom Milgrim and Blumberg and Mars-den despised, was laughing hardest of all.

Milgrim nodded to Halliday from the threshold and Halliday and Stearns rose. “Boys,” Milgrim addressed Blumberg and Mars-den, “have you met Manley Halliday?” The name was too faint an echo for Marsden, but Blumberg reacted as Milgrim had hoped he would.

“I’m one of your great admirers, Mr. Halliday.”

Milgrim looked proud. Halliday answered with his slight bow. “Thank you, sir,” he said. And Bill Ross, a signal light turned red or green on slightest pressure, now flashed: “It’s really a great honor to have you with us, Mr. Halliday.”

“Thank you, sir,” Halliday said again, and in the way he said this and bowed again, exactly as he had before, Shep felt the mockery.

“Sorry to keep you waiting, Manley.” When Milgrim moved in, the charm blew out hot and fast as from the suddenly opened door of a blast furnace. “Come on in.”

Feeling like an appendage of Halliday which did not need to be individually acknowledged, Shep followed them.

“Be sure to send those flowers to the plane and tell the Mar-keys I’d love to come if we didn’t have a preview,” Milgrim called to Peggy as the door closed her out.

“I didn’t think that last huddle would take more than five minutes,” Milgrim apologized again. “But sometimes I think writers have a genius for confusing simple things. A film story only needs one good problem—will the hero tame the shrew?— will the nice girl win her man back from the bitch ? I call it the furnace. Build your fire hot enough in the basement and you’ll generate heat right up to the top floor—or, in other words, to your climax. If my writers could only remember that, we’d save a million dollars a year.”

He paused to taste his metaphor and finding it good, he sighed luxuriously. “Before we pitch into your story, Manley …” the buzzer interrupted. “All right, put her on.” Then the change in voice, shamelessly winning: “Jean, have they ever criticized you for anything you wore in one of my pictures? … Darling, be a good girl, wear that evening gown. You’re the only gal in town with the figure to get away with it.”

That seemed to take care of Jean. Milgrim, with a wink to Halliday, picked up exactly where he had left off. “… Before we pitch into your story, Manley, are you perfectly comfortable? Office all right? Are you happy with Miss Boylan? Is this guy,” acknowledging Shep’s presence for the first time “giving you any trouble?”

“On the contrary,” Halliday said, “if all of them had Stearns’ awareness, I would have to revise my opinion of Hollywood writers.”

Everybody was pleased—the Great Man, the Great Author and the Young Man of Promise. At that moment Love on Ice had merely to be written and produced to result in an achievement reflecting credit on all three.

“I have a theory about this picture,” Milgrim announced. The buzzer signaled another call. This time it was the head of a rival studio from whom Milgrim wanted to borrow a ranking director. “Leo,” he fenced, “before you give me a quick answer, what if I should see my way clear to letting Jean Costello do an outside picture?” They decided to get together for lunch one day next week and talk the whole thing over. Once more Milgrim was able to come back to the conference as if he had never been away: “My theory is this, Manley. We’ve all seen college musicals from Good News on. And after a while they all begin to run together. Now I believe in being honest with my writers. I want this picture to be a money-maker. I’ve made my share of daring subjects and I will again. This time I want to play safe, in subject matter. But I want the quality to be top drawer. That’s what I hired you for, Manley. In other words I want to do a story that’s—well, let’s call it commercially sound—with fresh, believable characters, smart dialogue. I have a hunch we can put together an intelligent college musical without going highbrow. There was nothing sensationally new about Alexander’s Ragtime Band, for instance. Yet I wouldn’t have been ashamed to have my name on it. And you know how high my standards are.”

“In other words,” Halliday injected quietly, “you believe in teaching old dogs new tricks?”

“You bet I do!” Milgrim took him up enthusiastically. “That’s the surest route to profitable pictures I know. Take me, Manley, I’m an old dog. And I’m full of new tricks.”

He grinned at his own knack for improvisation. “And then once in a while, for variety’s sake, we try a new dog with old tricks. For instance, I’d like to talk with you about doing High Noon some time, Manley. Maybe together we could work out an angle.”

“I’d rather not have it done than see it made the way the Hays Office would make you do it,” Halliday said with a firmness that delighted Shep and even surprised himself.

“I wish my writers out here had that kind of integrity,” Mil-grim strung along. “I’m sick and tired of you Guild members—” he had suddenly turned on Shep “—complaining about being pushed around, squawking about control of material. Hell, most of you would be lost if we didn’t bring you back to sound principles. The ones who get pushed around,” he turned back to Manley, speaking less harshly, as if he were explaining all this to a guest touring the studio, “are those who deserve to get pushed around.”

“Didn’t Sorel say something like that in his Reflections on Violence?” Halliday asked.

“I’ll come clean with you, Manley. I wouldn’t know. I used to be an omnipotent reader when I was in college. But when do I get a chance to read? Scripts to study every night. I think the greatest luxury of my life is to sit down with a good book and not worry about what kind of a picture it’s going to make. This year I read Man’s Hope, by that French writer. Powerful. Simply powerful. But of course it could never make a picture. It’s one of those things we just can’t touch.”

The screenplay Shep hadn’t been able to sell had told the story of a young college graduate who goes to fight for the Loyalists.

“Much too controversial,” Milgrim answered his look. “See what happened to Wanger’s Blockade. The Legion of Decency made him cut the script to ribbons and the Knights of Columbus still picketed the picture.” Milgrim shook his head wisely. “When will producers ever learn to stay away from politics? I even think the Warners are nuts to make something like Confessions of a Nazi Spy. Damn it, no matter what we think of those countries personally, we’re still maintaining diplomatic relations, we’re still trying to do business with them.”

Before you stick your neck out too far, Shep tried to believe, let it grow a little stronger. But now, with Halliday sure to know what he was thinking, it was difficult to hide from himself. “But you can’t just lock ’politics’ in a little box and throw the key away, Mr. Milgrim. Politics are a lot closer to basic human drives than most people think.”

“ Halliday had been watching the face of the earnest young man. It was a strong face physically, with its irregular, European, un-aristocratic attractiveness that was just coming into style with John Garfield. Could it be depression values, Manley wondered, that turned women from the smooth boys with the slicked-down hair to these sturdier, more emotional, non-Anglo-Saxon heroes?

Halliday tried to bring his mind back to the point of discussion. It was all politics now. Just as everything was once reduced to religion, so everything now was forced into the overcrowded corral of politics. And such very simple politics.

The warning buzzer of the dictaphone and the insistent ringing of the phone snapped Milgrim back to the high-strung practicalities of picture-making. “Jimmy, I’ll be honest with you,” he was telling the agent on the other end (henceforth, Halliday warned himself, when he heard that phrase, on guard!) “I want Monica for the part. She’s absolutely right for the mother. But I’d shelve the picture before I’d pay her one-twenty-five. Hell, I could get Anderson for seventy-five and she wouldn’t be bad either. I’m being honest with you, Jimmy. I’m not trading this time. One hundred thousand for the picture, period. Why don’t you talk to Monica and call me back?”

Again he shook his head as he hung up, a man sorely put upon. “These goddam agents are going to put us out of business. Three years ago Monica Dawson was starving to death on Broadway. Now these agents get her so worked up her feelings are hurt if she’s only offered a hundred thousand dollars for five weeks’ work.”

A strange business, Halliday was thinking. These men are in business but they’re more emotional than business men. And they’re involved with art but they’re altogether too business-like for artists.

Milgrim rose and crossed the office into his private bathroom. The moment he was gone they looked at each other conspiringly. “Omnipotent,” Shep whispered. They shared the joke with silent satisfaction. It made them feel good: these little things in common that barely needed saying. Milgrim returned to the conference with a clear resolve to dispatch it efficiently. “Well, Man-ley, you’ve been thinking about our story for a day or two. Had any hot flashes yet?”

This was what he dreaded, the story conference. Despite everything that had happened he had never, or almost never, lost faith in himself. He had clung to the conviction that he could always lock himself up in his room and lock his mind up in his head, and his characters with it and let them go at it, let them begin to work, to catalyze—but that goes on inside, not out here, not here in public. And if you talk about them, talk them out of your head they may turn to stone or dust or, worst of all, words. So Manley Halliday did not know what to say. Those were only snow girls and boys in Love on Ice and the only result Halliday’s mind had on them so far was to melt them down to dirty puddles.

“We’ve dropped a few plumb lines down to try and get our bearings,” Halliday said uneasily.

Milgrim wasn’t altogether satisfied with that.

“Naturally, I don’t want to rush you,” Milgrim said, “but we haven’t got too much time. Pretty soon you’ll want to decide whether to keep Stearns’ line and improve on it or throw it all out and start from scratch.”

“We’ve been giving some thought to the two roommates,” Shep found himself saying. “We’ve thrown out the conventional foe Colleges I started with. We think one of the boys might be the son of the college’s richest trustee. And his roommate’s a campus radical who has to wash dishes in the school cafeteria and …” Shep was ad-libbing shamelessly. In the story conferences he had attended he had watched the talkers with a certain horrified fascination. The man with quick-silver ideas and a quick mouth could work small, tinseled miracles in the early conferences.

“Mmm-hmm, mm-hmm.” Milgrim nodded, watching Halliday for corroboration or amplification. “That might work. I’d like to hear it in more detail.”

“Victor, we haven’t really thought about your story at all yet.”

Halliday had been wanting to say that from the beginning.

“Oh?”

As in any game, from bike races to story conferences, the man who jumped off first had the advantage. Milgrim, who usually stayed on top of these conferences, was off balance now and Halliday, speaking with just the right note of dignified reserve, increased his lead.

“So far we’ve talked about my books, and about contemporary writing; and we’ve compared a few notes on our respective generations. But I don’t think we’ve been wasting our time.”

Not sure whether to be shocked or impressed, Milgrim said, “Well, Manley, at least I admire your frankness.” His tone was purposely ambiguous.

“In other words, Victor, we’ve been spending our time trying to get acquainted,” Halliday went on. “After all, you can hardly expect perfect strangers to shake hands for the first time and just sit right down and start working together. In many ways collaboration is just as complex as marriage—maybe a little more so.”

Milgrim chuckled uncertainly.

The Great Author had played his part nicely. After a momentary falter, he had struck an attitude of urbane intelligence that set him apart from the double-talkers who passed through Milgrim’s office. This was the difference between artists and hacks, Milgrim obviously had decided, between real authors and clever ad-libbers. This was going to be a great success and Darryl and Dave Selznick and Walter Wanger and the rest of them were going to be saying, “Isn’t that a typical Milgrim hunch for you—bringing back a famous has-been like Halliday?” Maybe they’d go on and do The Night’s High Noon— there were ways to get around the Hays Office. Of course you’d probably have to get the husband and wife together—the end would be a little too sordid otherwise, a little too down as Halliday had originally written it…

“Boys, could you get ready to take a little trip the day after tomorrow?”

“Catalina?” Halliday had heard from Ann about those trips on Victor’s boat. He’d invite his writers for a pleasure cruise and make them talk story all week-end. “A luxurious version of the Bedaux stretch-out,” Ann had called it.

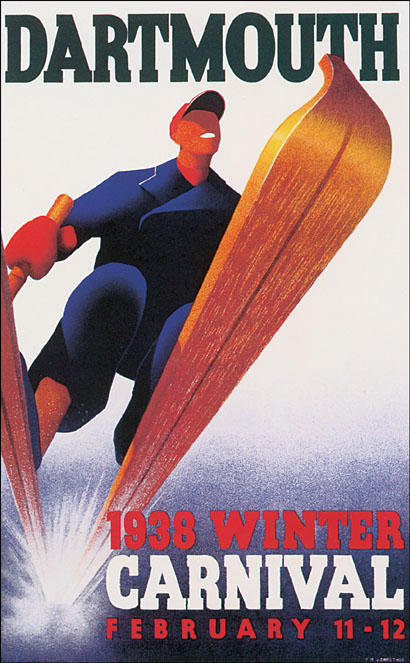

“No, we’ll do that when we get back, Manley. Next weekend’s the Webster Winter Mardi Gras. I’m sending a camera crew up there to get the background stuff. That’s why I’ll need you along. I’m not expecting a complete shooting script overnight exactly—”—only Milgrim smiled—“but the boys will need a pretty definite outline by the time we arrive.”

“But, Victor, couldn’t we work that out from here and phone or wire it to you?”

Milgrim shook his head. “After all, the thing that’s going to sell this picture is real college types. Your characters ’ll have to look like ’em, think like ’em, talk like ’em. I tell you a week-end up there’ll give you more fresh ideas than a month in the studio.”

The location trip had caught Halliday by surprise and he was vulnerable. The Mardi Gras meant distance and snow and ice and the discomfort of travel and the extra effort of having to be nice to strangers. And the lack of Ann.

“But, Victor, the ink is hardly dry on Stearns’ diploma and he seems to be a perceptive young man. I think he knows enough about how they look and talk and think. And since you’re in such a hurry for a line, I’m sure we could work faster here.”

To travel East with Manley Halliday, come back to Webster with him, show him off to Professor Croft and the other English professors, really get to know him … No less than Milgrim, Shep was impatient of Halliday’s protest.

“I wasn’t thinking so much about Shep,” Milgrim persisted. “I thought it would be a sort of refresher course for you, Manley. Those were terrific college scenes in the first part of Friends and Foes. But after all that was twenty years ago.”

“I remember the Mardi Gras,” Halliday said. “I don’t imagine it’s changed too much.”

“Maybe that’s one mistake we all make,” Milgrim said, obviously including himself for courtesy’s sake. “Imagining that things don’t change.”

Oh Christ, if I could just sit down somewhere and write his old movie for him, Halliday thought peevishly, without all this palaver, without having people constantly rubbing my nose in my own past, without all these additional difficulties, this trip— he’d have to talk Milgrim out of that idea. Travel, like wenching, was a young man’s game.

“Victor, do you really think it’s necessary for me to go all the way back to Webster? After all, if it’s just current collegiana you want me to brush up on, I could wander around U.C.L.A.”

“But that’s just what I don’t want—U.C.L.A. I want the richness, the—fine old atmosphere of the Ivy League.”

“You may not remember, but critics used to praise my photographic memory. I don’t have to travel three thousand miles to describe Webster.” He thought, but decided not to say: And how much of what we really know of a place ever reaches the screen anyway?

“Now stop talking like an old codger, Manley. The trip ’ll do you good.” Milgrim turned to Shep—using him when he needed him—with a wink. “Wait’ll he sees those Mardi Gras babes! It’ll make us both feel young, Manley.”

Halliday did not like it. He did not like it at all. He was in no mood for other people’s parties. He had already gone to too many of his own.

“Seriously, Victor. I’m—at your service, of course—but I hardly think it’s necessary for me to make this trip.”

“For goodness’ sake, Manley”—in Milgrim’s voice was the good humor of self-confident authority—“I’m not asking you to go to Tibet. What’s New York—fifteen hours—and another few hours to Webster. You’ll be back in a week.”

What had a week or a month or a continent or a hemisphere meant to him and Jere when the going was good? Hadn’t they crossed continents as casually as most people cross streets? Once they had chartered a plane from New York to New Orleans for Toni Michaud’s engagement party—and taken off again at 5 a.m. in their evening clothes to keep a date with Mencken in Baltimore. And the time Norman Kerry had called from Hollywood to tell them he wanted to give a party for them, to celebrate his playing Ted Bentley in that silent version of High Noon. Kerry had thought he was making a local call to them when actually they were at the Ritz in New York (his secretary having said merely that she had the Hallidays on the line). Instead of telling him they were three thousand miles away they had thought it simpler and more fun just to say they would come. So the next afternoon they went out on the Century. The party had been all right. They had stayed three months. He had even knocked out a magazine serial about the episode, collected in one of those amusing, quickly forgotten books, Around Hollywood in Ninety Days. After making over thirty thousand on the trip, it had still cost him money. But the real cost came much later, severe drafts on his spirit when he was already spiritually O.D. Yes, he had taken enough trains and planes and ships and cable cars and bicycles and ski-lifts to last him several lifetimes, certainly the one he was trying to live now.

“Victor, I …” (mightn’t be too wise to blame poor health: Harper had warned him of Milgrim’s dislike of unsuccessful people: failure to remain healthy might be held against him too.) “I really think the wisest thing is a division of labor. I could be straightening out the line while you and Stearns go East to …”

“Manley,” Milgrim’s tone was growing firmer, “naturally I want you to feel as comfortable as possible on this job. But unless your reason is unanswerable—doctor’s orders or something like that—I think you’d better arrange to leave the day after tomorrow.”

How could he tell this formidable man, this supremely positive man, this success: I do not want to leave Ann Loeb. I do not want to try to live without her, even for one week. / can’t live without you—the romantic cliche, essentially false, sometimes furthest from the truth, had gained, in his case, clinical validity. Could he live without Ann Loeb? He hoped to beg the question. He could not bring himself to marry her though. Not while Jere was alive. Maybe not even if he should outlive Jere. Yet in a way they were more married than ever he and Jere had been. After all, from the painful vantage of retrospect he and Jere had never really had a marriage. At its best (and ah how very good that was) it had been a prolonged honeymoon, or a series of honeymoons; suddenly his mind snatched a line from Saroyan’s tender vaudeville, “No foundation, all the way down the line …”

No, there had been no foundation, neither to his life nor to Jere, symbol of so much of his life. If only divorce could drive a woman out of mind as well as sight. If only she were dead and could be buried in hate or bitterness. If only he could dwell in the golden days. Or if only he could make his peace with the present. Hadn’t he the same claim on the present as Victor Milgrim or young Stearns?

“Another reason for going,” Milgrim was saying, “is I have to be in New York next week anyway, for a sales convention. So this’ll give us a chance to straighten out the story in New York and at Webster. I don’t want to tell you how to write your script, of course. But I usually have a few ideas—a few short cuts, call them that,” he added modestly. “Manley, I hate to bear down on you so hard, but that’s the picture business. I’ve got to count on you to come up with that line by the time we huddle in New York.”

As if to cut off any possible escape, Milgrim called Peggy in and told her to reserve transportation and a suite for them at the Waldorf. Halliday had an impulse to repeat his protest, to insist on remaining behind, flatly to refuse to accompany an expedition in which he could see no possible usefulness, and about which he actually felt a gnawing fear. But he was able to brush the impulse aside as mere neuroticism. All right, he’d go. Halliday, the good soldier. For these few weeks he’d move at Milgrim’s command. But then, by God, he’d show them. He’d show the doubters and the scoffers and those who, worst of all, had forgotten him entirely. He would be his own man again, with his own book. And it would be a book. As he sat there in Milgrim’s office, resigned to a tedious journey, his confidence grew. There would be ten dark weeks, but he’d get through somehow.

Still another story conference was gathering as Shep and Manley Halliday walked out together. “For a minute there I was afraid you were going to talk him out of it,” Shep said. “I hope you don’t mind going too much. I think we’ll have a swell trip.”

There are times, Halliday was thinking, when a young man, any young man, seems repulsively healthy to an old man of forty.

At times, Shep was thinking, his face looks as cold as stone and his eyes look three days dead.

Halliday’s voice seemed to escape in thin wisps from a deep hollow: “Son, I never like to dampen enthusiasm. But I made this swell trip twenty-three years ago.”

Next chapter 8

Published as The Disenchanted by Budd Schulberg (1950).