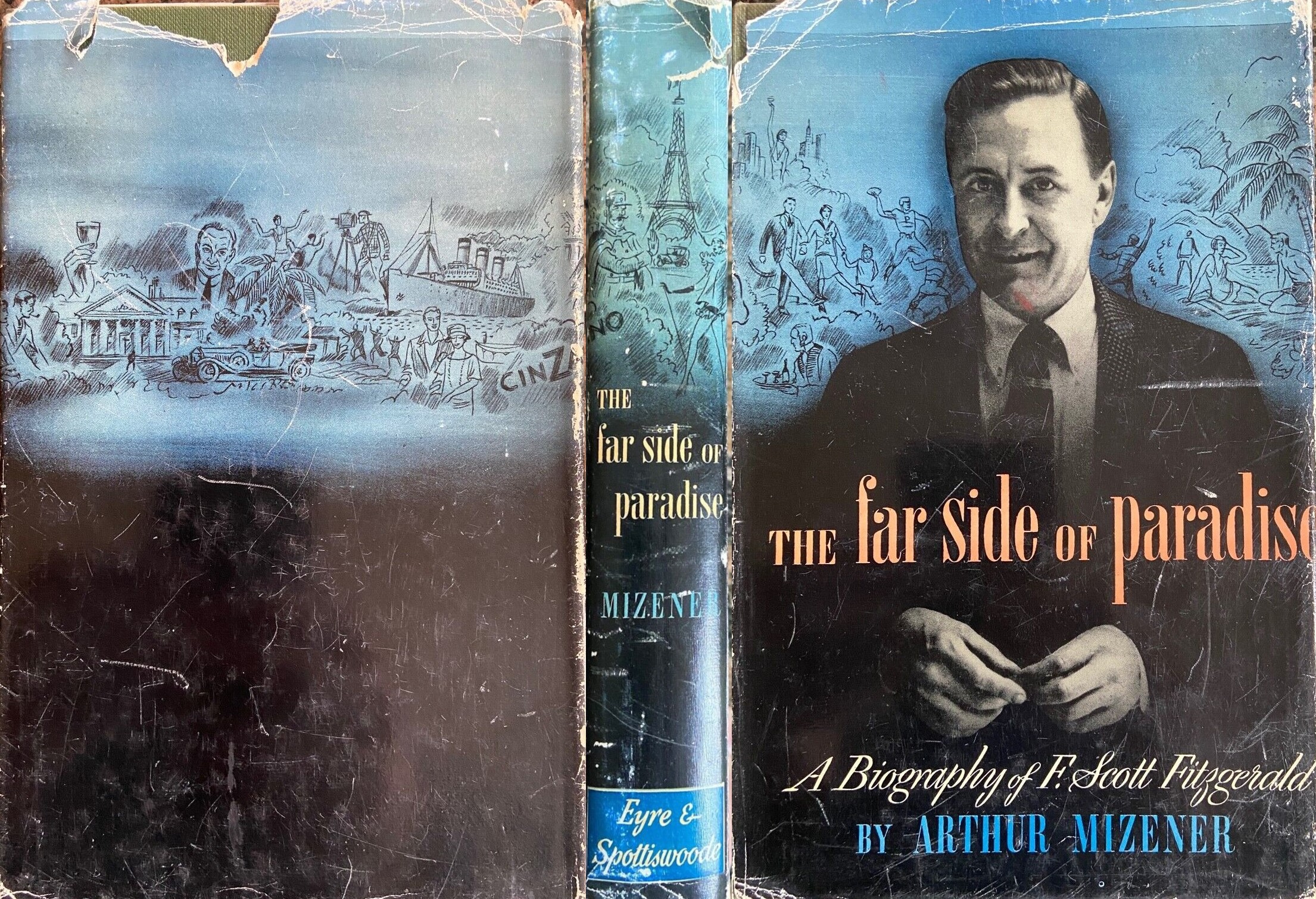

The Far Side of Paradise: A Biography Of F. Scott Fitzgerald

by Arthur Mizener

Chapter XI

They came backto America with the intention of settling down and living a more orderly life, so they started off by visiting Fitzgerald’s parents, who were now living in Washington, and Zelda’s family in Montgomery. Just after Christmas, however, Fitzgerald got a chance to fulfill his old threat to go to Hollywood and learn the movie business; John Considine of United Artists asked him to come out to do a “fine modern college story for Constance Talmadge” (“one of the hectic flapper comedies, in which Constance Talmadge has specialized for years,” the newspapers called it.) After some jockeying Fitzgerald agreed to go for $3500 down and $8500 on the acceptance of the story, for they needed the money too much to refuse an offer of this kind even if it was likely to interrupt their program of orderly living.

After a delay at El Paso (Fitzgerald was convinced he had appendicitis and insisted on leaving the train for a hospital), they reached Los Angeles and settled at the Ambassador. They were given a big welcome, receiving the royal recognition of lunch at Pickfair, making friends with Lillian Gish, and renewing their friendship with Carmel Myers, to whom Fitzgerald inscribed a copy of The Great Gatsby with his old gaiety: “For Carmel Myers from her Corrupter F. Scott Fitzgerald. ‘Don’t cry, little girl, maybe some day someone will come along who’ll make you a dishonest woman’ Los Angeles.” Almost immediately they found themselves part of a congenial group which included Carl Van Vechten, John Barrymore, Richard Barthelmess, and Lois Moran. Fitzgerald was fascinated by Lois Moran and she by him. She even persuaded him to have a screen test made in the hope that he might get a part as her leading man. By the time he came to write Tender Is the Night, Fitzgerald had decided to take a superior attitude toward this little scheme.

But she was important to his imagination and he put what she represented for him into the portrait of Rosemary Hoyt in Tender Is the Night. For a long time after this Hollywood visit she had his attention; he cut pictures of her from the newspapers at the time of her marriage, and among the notes of events he thought dramatic enough for stories is one about a visit she paid him in Baltimore. Like Dick Diver with Rosemary, he was charmed by her youth and beauty and innocence: he was thirty, and hated it, and she was twenty. It made him feel young again to be so extravagantly admired, but of course there is no evidence that his feeling for her was ever so mixed up with personal exhaustion as was Dick’s for Rosemary. This part of Dick’s story was the spoiled priest’s version of what was potential rather than actual in the relation.

There was a whirl of parties, night clubs, and practical jokes. At a tea of Carmel Myer’s Fitzgerald made himself what one gossip columnist described as “conspicuous by [his] presence” by collecting watches and jewelry from the guests and boiling the whole collection in a couple of cans of tomato soup on the kitchen stove. James Montgomery Flagg, who ended by being disgusted with the Fitzgeralds, spent the evening with them after the tea. They wound up, he remembered, sitting on the coping of the Ambassador’s parking place listening to Zelda sing a bawdy comic ballad. Fitzgerald, with a fifty-dollar tip, persuaded the Ambassador’s night starter to cash him a check for several hundred dollars; he wanted the money to hire a car because he and Zelda had become obsessedwith the idea that they must see John Monk Saunders, who, they asserted, was much too successful with women and ought to be altered; for that purpose they supplied themselves with scissors, bandages, and gauze at the hotel drugstore. They then routed Saunders out of bed and insisted on pulling open his bathrobe and urging everyone to observe how lovely his chest smelled. Saunders finally got rid of them, but all the way home Fitzgerald kept turning around to squint at Flagg and say “God! But you look old!” and Zelda told him about how, by signing Scott’s name to things she had written, she had got large prices for them. [Zelda wrote a number of pieces for College Humor, McCall's, and Esquire and signed them 'Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald.' The account Fitzgerald gave Perkins of ''Show Mr. and Mrs. F. to Number--'' and 'Auction-Model 1934' [Esquire, May, June, July, 1934) is probably substantially true of all the joint pieces. 'Zelda and I collaborated,' he said, '-idea, editing and padding being mine and most of the writing being hers.' (To Maxwell Perkins, May 15, 1934.) There were, however, at least two stories, one wholly and the other largely by Zelda, which were printed as Fitzgerald's. They were 'The Millionaire's Girl' (SEP, May 17, 1930) for which they got $4,000, and 'Our Own Movie Queen' (The Chicago Tribune, June 7, 1925) for which they received $1,000. When Harold Ober, who had innocently sold 'The Millionaire's Girl' to the Tost as a Fitzgerald story, discovered his mistake, he informed the Post at once. But the story was already in type and the Post let it stand.] “These charming young people,” Flagg said. To many people like Flagg they no longer seemed the Babes in the Woods they had been in New York five years before, who “simply got tight and pulled a lot of sophomoric pranks” that “never were mean or cruel or unkind.”

When Fitzgerald finally completed his story for Constance Talmadge it was rejected. “At that time,” he said years later, “I had been generally acknowledged for several years as the top American writer both seriously and, as far as prices went, popularly. I … was confidant to the point of conciet. Hollywood made a big fuss over us and the ladies all looked very beautiful to a man of thirty. I honestly believed that with no effort on my part I was a sort of magician with words…. Total result—a great time and no work. I was to be paid only a small amount unless they made my picture—they didn’t.”

But this account implies less of an effort on his part than he actually made. Lipstick is a competently plotted if conventional Cinderella story about a girl at a prom. Though Fitzgerald did not name Princeton, he drew on its geography and customs for background and there is an authenticity about the prom scenes, the proctors, the Nassau Club, and the undergraduates which is rare in the movies at any time; “the young men are dressed in knickerbockers that are not too big, flannels not too wide or in ‘business’ suits that have no collegeatesmack about them… for this is one of the oldest and most conservative of eastern universities… and its manners are simply the good manners of the world outside.”

As soon as the script was finished the Fitzgeralds left Hollywood. It was reported that they stacked all the furniture in the center of their room at the Ambassador, put their unpaid bills on top of it, and departed; when they got on the train they crawled on their hands and knees the length of the car to reach their compartment, to escape inconspicuously. … BOOTLEGGERS GONE OUT OF BUSINESS COTTON CLUB CLOSED ALL FLAGS AT HALF MAST … BOTTLES OF LOVE TO YOU BOTH, Lois Moran wired them.

The orderly life, which had been in abeyance during these months, was now revived. With the help of Fitzgerald’s college friend, John Biggs, they found a beautiful old Greek-revival mansion outside Wilmington called Ellerslie. “The squareness of the rooms and the sweep of the columns,” wrote Zelda, “were to bring us a judicious tranquility.” Fitzgerald addressed himself to the world situation and gave an interview in which he announced that he was very disturbed about it, that the mushiness and ineffectuality of liberalism compelled people to turn toward “The Mussolini-Ludendorff idea,” that he deplored Mussolini in particular but that his hope for the nation lay “in the birth of a hero who will be of age when America’s testing comes.” He also settled down to an honest struggle to complete his novel. He was realistic enough to warn Perkins against any publicity about it, but wired him that he expect[ed] to deliver noveL to liberty in june. They made an effort to become a part of the social life in Wilmington and, as they always did when they tried, they charmed everyone and were soon firmly established there.

But like all their homes, Ellerslie did not work out very well. It was, as one of their friends remarked, a big house with not enough rooms, and tranquillity was not easily won, for under the stress of the accumulated disorder of their lives theirown personal relations were gradually deteriorating into what Fitzgerald later called an “organized cat and dog fight.” Their social success in Wilmington was the signal for that destructive impulse which was the product of Fitzgerald’s unhappiness to assert itself, and he began to be rude to people. At the same time his complementary impulse to take upon himself the responsibility for making a group of people happy showed itself at the many week-end house parties they gave. For one such party he invented an elaborate game of polo played on farm horses with croquet mallets. Like much that he did, this game was symbolic, an ironic imitation of the lives of the Tom Buchanans of the world and their strings of polo ponies. He exerted himself endlessly in this way to make his guests happy, for “like most people who love a good time,” as Zelda wrote after his death, “he kept happiness constantly in mind except toward the end when he grew embittered.”

As a part of their struggle for tranquillity they had their parents come for visits. Zelda spent two busy months building a marvelous dollhouse for Scottie; she made a set of charming lampshades decorated with découpages of all the houses they had ever lived in and of members of the family and the servants riding on the various animals they had owned; she painted the garden furniture with decorative and ingenious maps of France. They celebrated Christmas with an elaborate tree. Fitzgerald put himself on a drinking schedule, though there were occasions like the one where, having made a friend a cocktail and asserted he was not drinking, he idly poured himself a glass of gin and drank it off and then said with evident surprise: “Did I just drink a glass of gin?—I believe I did.”

Being near Princeton he went back there for the first time in several years to find that he “really loved the place.” This affection for Princeton led him to think of himself as a football expert again and to attend the games assiduously. This compensatory interest in football endured for the rest of his life. He liked to advise the Princeton authorities, and he oncecalled Asa Bushnell at four in the morning to pass along an idea for a two-platoon system (one was to be a “pony” team, which shows the source of this idea in Fitzgerald’s own daydream of football heroism). Bushnell passed this Old Grad problem along to Crisler, who wrote Fitzgerald: “… your new Princeton System has… many virtues. I will use it on one condition. Namely, that you will… take full credit for its success and full blame for its failure, if any.” Fitzgerald replied: “I guess we’d better hold the… System in reserve.” His revived interest in Princeton also led him to accept when Cottage Club asked him to come to the club and make a speech on a program of lectures by distinguished alumni of the club. When he got up to speak he found himself, in spite of having taken a fair number of relaxing drinks, badly frightened by a Princeton audience. He stumbled through a few sentences and then, muttering to himself in an audible whisper, “God, I’m a rotten speaker!” gave up altogether and sat down.

He also got in a good deal of work on his book during this summer of 1927, the first for some time. He was full of optimism and talked confidently of how what he was now calling The World’s Fair would “before so very long begin to appear in Liberty.” The work, however, petered out during the fall, and when Perkins inquired in February—he thought he needed to know about spring publication—Fitzgerald wrote in despair: “Novel not yet finished. Christ I wish it were!” Work came to a complete stop when they decided to spend the summer of 1928 abroad.

This decision seems to have been reached because of a restlessness which no squareness of rooms or sweep of columns could subdue. But their immediate reason for going was Zelda’s dancing. She had determined suddenly to become a ballet dancer and, almost from one day to the next, had taken to dancing with an intensity which, as one of their friends said, was like the dancing madness of the middle ages. Shebegan to go to Philadelphia two or three times a week to study with Catherine Littlefield and would come home to practice several hours a day in the living room, which was cleared for the purpose. There was something peculiar about this extreme concentration on dancing and Fitzgerald afterwards said that looking back he thought he could trace evidences of her insanity at least as early as 1927, when she had begun to show a number of disturbing signs, such as going through long periods of unbroken silence. Her effort to make a career for herself was touching, too, for as Alabama Knight had said to her child, “I believe I could be a whole world to myself if I didn’t like living in Daddy’s better”; there was getting to be less and less of his world for her to live in, and this as well as her ambition must have carried her along, “lost and driven now,” as she said, “like the rest.”

From the time she was a girl—when a Montgomery paper said with Southern gallantry that “she might dance like Pavlova if her nimble feet were not so busy keeping up with the pace a string of young but ardent admirers set for her”—she had wanted to be a dancer. This ambition had dissipated itself, like so much else in their lives, in parties. Now, when it was too late—good dancers start training as children and Zelda was approaching twenty-eight—she was concentrating feverishly on dancing. She was still very beautiful. “Her once fair hair [which] had darkened” by this time to a “thick, dark, gold” framed a face which was, Sara Murphy said, “rather like a young Indian’s face, except for the smouldering eyes. At night, I remember, if she was excited, they turned black—& impenetrable—but always full of impatience—at something—, the world I think.” But the only effect of this beauty on her career as a dancer was to get her offers from the Folies Bergère.

They arrived in Paris in a haze of alcohol, without reservations or plans. A friend who met them finally got them a place to stay—it was not easy in Paris the summer of 1928. Scottie,who was excited by Paris, kept pointing out the sights as they drove through the city but neither of them was capable of responding. The summer was like that. Twice Fitzgerald wound up in jail. Zelda was starting to take lessons with Egarova and they quarreled over her dancing, for there was some drive in Fitzgerald to destroy her concentration. He appeared unable to endure Zelda’s successful—if neurotic—display of will when he felt that self-indulgence and dissipation were ruining him. “It is the loose-ends,” as Zelda said long after, “with which men hang themselves.”

Just before they returned to America they had a bitter quarrel during which unbelievable charges were made by both of them. This quarrel led to a break between them which was never really repaired. Late in September, “in a blaze,” as Fitzgerald said, “of work & liquor” (he was trying to finish up “The Captured Shadow” for the Post) they came home to Ellerslie. “Thirty two years old,” Fitzgerald wrote in his Ledger, “and sore as hell about it.” They were broke, though Fitzgerald’s income—including a $6000 advance on his novel—had been $29,737 in 1927 and was running close to that in 1928.

Back at Ellerslie Fitzgerald tried to settle down to his book. In November he wrote Perkins that he was going to send him two chapters a month of the final version until, by February, he would have sent it all. “I think this will help me get it straight in my own mind,” he said, “—I’ve been alone with it too long.” The November chapters were sent, and probably the December ones; but that was all. Four years later he asked Perkins to return “that discarded beginning that I gave you…”

He had brought back from France a kind of handyman—butler, chauffeur, and valet—named Philippe. Philippe had been a professional boxer, and he and Fitzgerald used to go out on the town together; friends spent a good deal of time late at night getting them home from the police station. Ashis frustration and bitterness increased, Fitzgerald became more difficult and his tendency to strike out at other people when he had been drinking grew on him. Gradually he became aware that an important change in his understanding of things—and perhaps in the things themselves—was taking place.

By this time contemporaries of mine had begun to dissappear into the dark maw of violence. A classmate killed his wife and himself on Long Island, another tumbled “accidentally” from a skyscraper in Philadelphia, another purposefully from a skyscraper in New York. One was killed in a speak-easy in Chicago; another was beaten to death in a speak-easy in New York and crawled home to the Princeton Club to die; still another had his skull crushed by a maniac’s ax in an insane asylum where he was confined. These are not catastrophes that I went out of my way to look for—these were my friends; moreover, these things happened not during the depression but during the boom.

In the spring of 1929 their two-year lease on Ellerslie ended and, writing the whole thing off as a bad investment, they set off for Europe once more. Fitzgerald explained to Perkins that he could not work in Delaware but that, once abroad, he would finish the novel by October. They had observed, the previous summer, the flood of “fantastic neanderthals who believed something, something vague, that you remembered from a very cheap novel” who were pouring into Paris, so they took an Italian boat to Genoa, heading for the Riviera. It was a rough trip, during which they both got involved in idle flirtations over which they quarreled. They were soon back in Paris, where Zelda continued to work hard on her dancing—“dancing & sweating,” as Fitzgerald noted with rising irritation. Their lives were drawing further and further apart as Zelda gave all of her waking hours to her dancing; but, like the heroine of Save Me the Waltz, she kept remembering that if “the careless happy passages of their first married life could [not] be repeated—or relished if they were, drained as they had been of the experiences they held—still, the highest points of concrete enjoyment that [she] visualized when she thought of happiness, lay in the memories they held.”

Fitzgerald became more difficult when he was drinking as he became more unhappy over his inability not to do so, and it only made matters worse for him that, when he was sober, he saw clearly what was happening and could describe it to others perfectly objectively.

My latest tendency is to collapse about 11:00 and, with tears flowing from my eyes or the gin rising to their level and leaking over, tell interested friends or acquaintances that I haven’t a friend in the world and likewise care for nobody, generally including Zelda, and often implying current company—after which the current company tend to become less current and I wake up in strange [places]… when drunk I make them all pay and pay and pay.

It was in fact even worse for him than that suggests, since even when he was drunk, if he thought about it, he understood what he was doing, as when he wrote John Bishop about “the sensuality that is your bête noire to such an extent that you can no longer see it black, like me in my drunkenness”—and then added in a P.S., “Excuse Christ-like tone of letter. Began tippling at page 2 and am now positively holy (like Dostoevsky’s non-stinking monk).” But this knowledge only made his predicament more painful to him. He fancied that people were beginning to avoid him and that there was even in Hemingway’s attitude a certain coldness. He took to brooding darkly over compliments until he had persuaded himself they were ironicand insulting. On the strength of a remark of Gertrude Stein’s comparing “his flame” with Hemingway’s, he wrote Hemingway a belligerent letter about his air of superiority. Hemingway replied withpainstaking care. But late in the year there was more trouble.

During the spring and summer of 1929 Hemingway had been boxing regularly with Morley Callaghan, and once Fitzgerald persuaded them to let him come along and keep time for them. During the second round that day, Hemingway for some reason began to fight with considerable seriousness and Callaghan, much the lighter man, had to hit faster and harder to keep clear of Hemingway’s now weightier punches. As the fighting became fiercer, Fitzgerald was so fascinated that he forgot to keep track of the time, and it was only when Callaghan stepped inside one of Hemingway’s wild swings, caught him squarely on the jaw, and dropped him that Fitzgerald came to. Instead of concealing his error, he said in his characteristically impulsive way, “Oh, my God! I let the round go four minutes.” Hemingway propped himself on his elbow and looked at Fitzgerald. “Christ!” he said, and then, after a pause, “All right, Scott. If you want to see me getting the shit knocked out of me, just say so. Only don’t say you made a mistake.” Fitzgerald was appalled by this; his face ashen, he drew Callaghan aside and said, “He thinks I did it on purpose. Why would I do it on purpose?” Then everyone began making an effort to put a good face on things and, as Callaghan concludes, “we all behaved splendidly. We struck up a graceful camaraderie…. And no one watching us sitting at the bar [later] could have imagined that Scott’s pride had been shattered.”

Sometime later a lively but inaccurate account of this episode was picked up by a gossip columnist for the Denver Post. According to this account, Hemingway had spoken slightingly of a fight story of Callaghan’s, saying Callaghan knew nothing about boxing (he had), and Callaghan had challenged him to fight and knocked him out. This story was repeated by Isabel Paterson in the Herald Tribune. Hemingway took the whole affair with the utmost seriousness; “something within him drove him to want to be expert at every occupation hetouched,” as Callaghan observed, and his vanity was particularly tender when his athletic prowess was in question. He persuaded Fitzgerald, against Fitzgerald’s better judgment, to cable Callaghan (collect): have seen story in herald tribune. ernest and I await your correction. Callaghan had in fact already sent the Herald Tribune a good-humored correction:

Nor did I ever challenge Hemingway. Eight or nine times we went boxing last summer trying to work up a sweat and an increased eagerness for an extra glass of beer afterwards. We never had an audience. Nor did I ever knock out Hemingway. Once we had a timekeeper. If there was any kind of remarkable performance that afternoon the timekeeper deserves the applause. … I do wish you’d correct that story or I’ll never be able to go to New York again for fear of being knocked out.

Fitzgerald’s cable, however, made him really angry. He was in no way responsible for the story; what was Fitzgerald doing cabling him as if he had spread it, had now been caught out, and owed everyone an apology? He spoke so bitterly about the whole affair that word of his feelings eventually got back to Hemingway and he wrote to say he had made Fitzgerald send the cable.

But the tensions that underlay the real affection Fitzgerald and Hemingway felt for one another could not be concealed when Fitzgerald was drinking. One night not long after this episode he began to reiterate monotonously that he was going to quarrel with Hemingway, that he felt a need to smash him, Eventually Hemingway was goaded into making a resentful reference to Fitzgerald’s timekeeping, and Fitzgerald then asserted that Hemingway had accused him of dishonorable conduct. Again a painstaking letter of explanation from Hemingway smoothed things over after a fashion. Fitzgerald was probably right in his feeling that Hemingway, in a differentway, was as complicated and emotionally disturbed a man as he was. But Hemingway, with his disciplined concealment of every attitude that did not belong to his carefully designed public self, had far more self-control.

But even such self-control as Fitzgerald had was breaking down badly, and in his suffering he struck out, blindly and unreasonably, at the people and things that mattered most to him. He was, as he knew, striking at himself. He was most sensitive about his failure to finish his book and once said to a newly introduced young writer who paid him a conventional compliment on This Side of Paradise: “You mention that book again and I’ll slug you.”

They went as usual that summer to the Riviera and took a villa at Cannes, but everything at the Cap d’Antibes seemed changed for the worse. Zelda had one or two small engagements at Nice and Cannes and was working harder than ever at her dancing, and that led to more “rows and indifference” between them. In June Fitzgerald had a new idea for his novel and told Perkins that he was “working night and day” on it. His new plan was to drop the matricide story he had been working on for such a long time and to write a story much like that of Tender Is the Night. The new novel was to be called The Drunkard’s Holiday. This new idea involved him in a fresh effort to analyze Gerald Murphy, who, combined with Fitzgerald, was to be the hero of the new book. This analysis got to be too much for the Murphys, for when Fitzgerald was drinking he did not hesitate to give them the benefit of it. “You can’t,” Sara Murphy wrote him, “expect anyone to like or stand a Continual feeling of analysis & sub-analysis, & criticism—on the whole unfriendly—such as we have felt for quite awhile. It is definitely in the air,—& quite unpleasant. … If Gerald was ‘rude’ in getting up & leaving a party that had gotten quite bad,—then he was rude to the Hemingways and MacLeishes too. No, it is hardly likelythat you would stick at a thing like manners—it is more probably some theory you have—(it may be something to do with the book)…;” However hard on the Murphys this new conception of his subject was, it did get him started again on his book; during most of September he was hard at work and much encouraged.

In October they started north for Paris, spending the night of the stock market crash at the Beau Rivage in St. Raphaël, “in the room Ring Lardner had occupied another year [when he visited them there in 1924].”

We got out as soon as we could because we had been there so many times before—it is sadder to find the past again and find it inadequate to the present than it is to have it elude you and remain forever a harmonious conception of memory.

Back in Paris they found an apartment at 10 rue Pergolèse and life went on much as it had the previous winter. It was a heart-breaking time for Zelda; she had been encouraged about her dancing that summer and she had reached the time when she ought to have been getting some professional offers. It was the moment of success or failure. All winter she kept hoping the people who came to the studio were emissaries of Diaghilev ready to offer her at least bit parts in one of his ballets; and each time they turned out to be people from the Folies Bergère “who thought they might make her into an American shimmy dancer.” In February, “because it was a trying winter and to forget bad times,” they took a sight-seeing trip to Algiers.

Fitzgerald used this trip as part of the background for a story he wrote five months later and called “One Trip Abroad.” The story summarized their lives up to the time of Zelda’s breakdown. It deals with two! attractive young Americans, Nicole and Nelson Kelly, who have inheritedmoney and come to Europe to live the good life, he to paint and she to sing. They start going about on the Riviera with a group of people one character describes as a “crowd of drunks… [who have] shifted down through Europe like nails in a sack of wheat, till they stick out of it a little into the Mediterranean Sea,” people who are “somewhat worn away inside by fifteen years of a particular set in Paris.” The Kellys break away from this set to join another which is intellectually superior but fundamentally quite as frivolous. As they gradually harden Nelson takes to drink. Eventually they both break down physically and go to Switzerland, “a country where very few things begin, but many things end,” to recuperate. There they try to take stock of themselves and, “worn away inside,” to regain their old self-contained world. But they find themselves without peace, often wanting company desperately; and Nelson sees his face in a bar mirror “weak and self-indulgent… the kind of face that needs half a dozen drinks really to open the eyes and stiffen the mouth up to normal.”

Nicole expresses their bewilderment:

It’s just that we don’t understand what’s the matter. Why did we lose peace and love and health, one after the other? If we knew, if there was anybody to tell us, I believe we could try. I’d try so hard.

They had set out to fulfill their vision of the good life, a life essentially passive and dependent on outside stimuli, a confused and pathetic vision of beautiful, “civilized” places, “interesting,” well-to-do people, and some pleasant way of being serious artists. They ended in emotional bankruptcy. This is Fitzgerald’s personal and compassionate version of the story D. H. Lawrence told angrily in “Things” and Hemingway satirically in “Mr. and Mrs. Elliot.” It is the spoiled priest’s preliminary evaluation of their lives during the decade sincethe success of This Side of Paradise, an evaluation Fitzgerald was to work out carefully during the next three years in the story of Nicole and Dick Diver.

When they got back from their trip, Zelda, fighting off the knowledge of failure, went back to dancing harder than ever. She appeared frighteningly tensed up. Early in April, at a large luncheon at their apartment in the rue Pergolèse, she became so nervous for fear she would be late for her dancing lesson that an old friend offered, in the middle of luncheon, to take her to it. In the cab she was badly overwrought, shook uncontrollably, and tried to change into her ballet costume as they drove along. When they got into a traffic jam, she leapt out and started running. This episode was so disturbing that Zelda was persuaded to stop her lessons for a rest. But she soon returned to them, and, on April 23, she broke down completely.

At first in her illness she would not see Fitzgerald at all, carrying over into her hallucinations many of the fantastic suspicions which had been a growing part of their quarrels from as far back as the fall of 1928. This suspicion of him gradually faded out. But her general condition did not improve; there were long periods of madness interspersed with periods of relative lucidity throughout the summer. During the calmer times she painted a little and wrote a great deal, producing a libretto for a ballet and three short stories. There is something at once pathetic and frightening about the persistence of her will to produce during this period. Fitzgerald realized how important the stories were to her and wrote Perkins a note about them when they were submitted to Scribner’s Magazine. “I think you’ll see,” he said, “that apart from the beauty and richness of the writing they have a strange haunting and evocative quality that is absolutely new. I think too that there is a certain unity apparent in them—their actual unity is a fact because each of them is the story of her life when things for a while seemed to have broughther to the edge of madness and despair.” [In November, 1930, Scribner's Magazine bought a story that Perkins called 'Miss Bessie' (a story called 'Miss Ella' was printed in Scribner's Magazine, December, 1931). This story had been the rounds of the high-priced magazines. Zelda's 'Millionaire's Girl' was printed in The Saturday Evening Post, May 17, 1930. The other stories were 'A Workman,' 'The Drouth and the Flood,' and 'The House.'] When Scribner’s rejected the stories, Fitzgerald tried to get Perkins to make a book of them and the “series of eight portraits that attracted so much attention in College Humor” during the previous year. [There are only seven such pieces in College Humor: 'Looking Back Eight Years' (June, 1928), 'Who Can Fall in Love After Thirty' (October, 1928), 'The Original Follies Girl' (July, 1929), 'The Poor Working Girl' (January, 1931, but written in 1929), 'The Southern Girl' (October, 1929), 'The Girl the Prince Liked' (February, 1930), 'The Girl with Talent' (April, 1930). Zelda remarked much later that these stories were potboilers written to pay for her ballet lessons, but they are better than that (Zelda to H. D. Piper).] But this scheme failed too.

When Zelda did not improve, Fitzgerald decided to take her to Switzerland, where, he was told, the finest psychiatric care in Europe was to be had. They went to Montreux, where a number of specialists were called in; they agreed on the diagnosis of schizophrenia. Fitzgerald was told that out of every four such cases one made a complete recovery, and two made partial ones. But there followed a summer and fall of dreadful anxiety; with no let-up except for a single hour in September, the terrible hallucinations and the violent eczema which characterized Zelda’s case continued through 1930, and Fitzgerald remembered with special horror “that Christmas in Switzerland” when Scottie came on from Paris and he tried to make it gay for her. There is a faint echo of what Zelda must have gone through in her description of Alabama’s delirium in Save Me the Waltz.

Fitzgerald had his moments of respite from the strain of watching Zelda suffer. He met Thomas Wolfe in Lausanne, where he was staying, and liked and admired him; they drank and talked endlessly together. Fitzgerald was specially charmed by Wolfe’s ability to keep things in an uproar. One night when he and Wolfe were arguing in the street, Wolfe gesticulated so vehemently that he struck a power line far above Fitzgerald’s head, snapped it, and plunged the whole community into darkness. They had to flee across the border to escape the police. There was a trip to Munich with Gerald Murphy and some skiing at Gstaad. When his father died in January he went home for the funeral at Rockville, Maryland, and paid a flying visit to the Sayres in Montgomery. Under other circumstances, his father’s death would have disturbed him as much as he was to feel several years later that it had.But for the moment, as he wrote his cousin Ceci, “all those days in America seem sort of blurred and dream-like now.” His visit to Montgomery was not pleasant, for though Mrs. Sayre stood up for him staunchly, as she always did, Judge Sayre was far from trusting his ability to take proper care of Zelda.

Apart from fortnightly trips to see Scottie, who had been left in Paris with a governess in order that her education might not be interrupted, he stayed close to Zelda in Switzerland most of the time. “[Nervous trouble],” said Zelda with that simple courage which characterized her attitude toward her illness, “is worse always on the people who care than on the person who’s ill.” It was Fitzgerald’s nature to feel deeply the suffering of the person he most loved; something of what he felt during these months must have gone into his description of Doctor Diver’s anonymous patient who, suffering from “nervous eczema” like a person “imprisoned in the Iron Maiden,” was yet “coherent, even brilliant, within the limits of her special hallucinations.” Moreover, despite the doctors’ assurances that Zelda’s trouble went back a long way and that nothing he could have done would have prevented it, Fitzgerald had a deep feeling of guilt about it. He knew how much he was to blame for the irregularity of their lives; he knew what he had contributed to that “complete and never entirely renewed break of confidence” which had occurred in Paris in 1928; he knew—however unreasonable Zelda may have been about her dancing—how much harder he had made it for her. When the doctors told him that he “must not drink anything, not even wine, for a year, because drinking in the past was one of the things that haunted [Zelda] in her delirium,” they were the voice of his own conscience.

He put all his feelings of guilt and pity, as well as his determination to make what restitution he could, into Charles Wales in “Babylon Revisited.” The situations differ, but Wales’ feelings are Fitzgerald’s:

… back in his room he couldn’t sleep. The image of Helen haunted him. Helen whom he had loved so until they had senselessly begun to abuse each other’s love, tear it into shreds. On that terrible February night … a slow quarrel had gone on for hours. There was a scene at the Florida, and then he attempted to take her home, and then she kissed young Webb at a table; after that there was what she had hysterically said…. They were “reconciled,” but that was the beginning of the end….

Late in January, 1931, Zelda got well enough to spend whole days out skiing, and Fitzgerald’s hopes that she was “almost well—really well” rose. She continued to improve until by spring she was able to travel a little. “Zelda is so much better,” Fitzgerald wrote Perkins, “… she’s herself again now, tho’ not yet strong.” They went to Annecy and Menton, swam and played tennis and danced. “It was like the good gone times,” Zelda said, “when we still believed in summer hotels and the philosophies of popular songs. … we danced a Wiener waltz, and just simply swep’ around.” Later, when she knew what a temporary respite it had been, she called this with bitter humor her “vacation from the nut-farm last summer [at] Annecy.” Toward the end of the summer they ventured farther, to Munich and Vienna. By September Zelda was well enough to go home, and they motored—“that is, we sat nervously in our six horse-power Renault”—to Paris and sailed for America, where they went to Montgomery with some idea of settling down quietly there. For a month or so they played golf and tennis and house-hunted, and Fitzgerald, as on all such homely occasions, found life dull.

When Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer asked him to do a revision on a script of Katherine Brush’s Red-Headed Woman, he was glad to go to Hollywood. There he saw friends like Carmel Myers, talked nostalgically with his old rival Dorothy Speare,the author of Dancers in the Dark, and, arriving at a party-one night at Carmel Myers’, went straight upstairs for a bath. His old feeling of excitement about the movies came back to him and he got his beautifully defined feelings about Hollywood—its color and scale, its fantasy, the sadness of the occasional fine mind caught in all this falseness and shoddy—into “Crazy Sunday,” the story he wrote when he got back to Montgomery in January. Fitzgerald's original idea was to do an article to be called Hollywood Revisited. He had some of it written when he decided to do a story instead. The story was turned down by both the Post and Scribner's; Fitzgerald's comment on its publication in The American Mercury was: 'Think Mencken bought it for financial value of name.'. Crazy Sunday is another case of Fitzgerald's making a hero of a friend (in this case Dwight Taylor) but 'clinging to his own innards.'

But he remembered this as a time of failure.

… while all was serene on top, with [Zelda] apparently recovered in Montgomery, I was jittery underneath and beginning to drink more than I ought to. … I ran afoul of a bastard named——, since a suicide, and let myself be gyped out of command. I wrote the picture & he changed as I wrote…. Result—a bad script. I left with the money… but disillusioned and disgusted, vowing never to go back, tho they said it wasn’t my fault & asked me to stay. I wanted to get east … to see how [Zelda] was. This was later interpreted as “running out on them” & held against me.

While Fitzgerald had been in Hollywood, Judge Sayre had died. At first Zelda seemed to take the shock well, but her father was important to her and his death was bound to affect her gravely. The first sign of trouble was an attack of asthma. Fitzgerald took her to St. Petersburg hoping the climate might help her, but she grew worse, and then, at the end of January, she broke down mentally again. This breakdown was a stunning blow to them. They had fought hard to believe Zelda was really well and their personal relations had recently been much happier. “The nine months before her second breakdown,” Fitzgerald said shortly after, “were the happiest of my life and I think, save for the agonies of her father’s death, the happiest of hers.” By this time he had read enough about schizophrenia to know that each attack made a final recovery less likely. He was a long way from giving up, but he was frightened and depressed.

He took Zelda to Baltimore for treatment and returned to Montgomery to await word from the doctors. A little more than a month later—it was written in six weeks, mostly while she was in the hospital—Zelda sent Perkins the manuscript of her novel, Save Me the Waltz (“we danced a Wiener waltz, and just simply swep’ around”). Like everything else she wrote, it was a brilliant piece of amateur work written at remarkable and disturbing speed. As Fitzgerald said years later, “She was a great original in her way, with perhaps a more intense flame at its highest than I ever had, but she tried and is still trying to solve all ethical and moral problems on her own, without benefit of the thousands dead.” A suspicion of Scott—the result of that fierce desire to succeed on her own and outdo him which haunted their devotion—made her send the book directly to Perkins. Its central section was an attack on Fitzgerald. Perkins and Fitzgerald worked together to get her to make the revision of this section which was published.

Fitzgerald’s main concern was for the effect of the book on Zelda’s mental state. “If she has a success coming,” he wrote Perkins, “she must associate it with work done in a workmanlike manner for its own sake, and part of it done fatigued and uninspired, and part of it done when even to remember the original inspiration and impetus is a psychological trick. She must not try to follow the pattern of my trail which is of course blazed distinctly on her mind.”

Zelda did not improve, and that spring Fitzgerald moved himself and Scottie from Montgomery to Baltimore and began to house-hunt. He found before long what was to be their home for the next year and a half, and for all the unhappiness they knew there, it was a lucky find. A large rambling brown Victorian house called La Paix on the Bayard Turnbulls’ estate at Rodgers Forge, it had been built by Mr.Turnbull’s father as a summer home in the nineteenth century. The Turnbulls themselves, whom Fitzgerald came to admire greatly, lived within sight in a house they had recently built for themselves. Here he and Scottie settled down as near Zelda as possible. Gradually she improved enough to be at La Paix more and more of the time. In June Fitzgerald was able to take her to Virginia Beach, and they returned to settle at La Paix. “We have a soft shady place here,” Zelda wrote Perkins, “that’s like a paintless playhouse abandoned when the family grew up. It’s surrounded by apologetic trees and warning meadows and creaking insects and is gutted of its aura by many comfortable bedrooms.”

Next chapter 12

Published as The Far Side Of Paradise: A Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald by Arthur Mizener (Rev. ed. - New York: Vintage Books, 1965; first edition - Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1951).