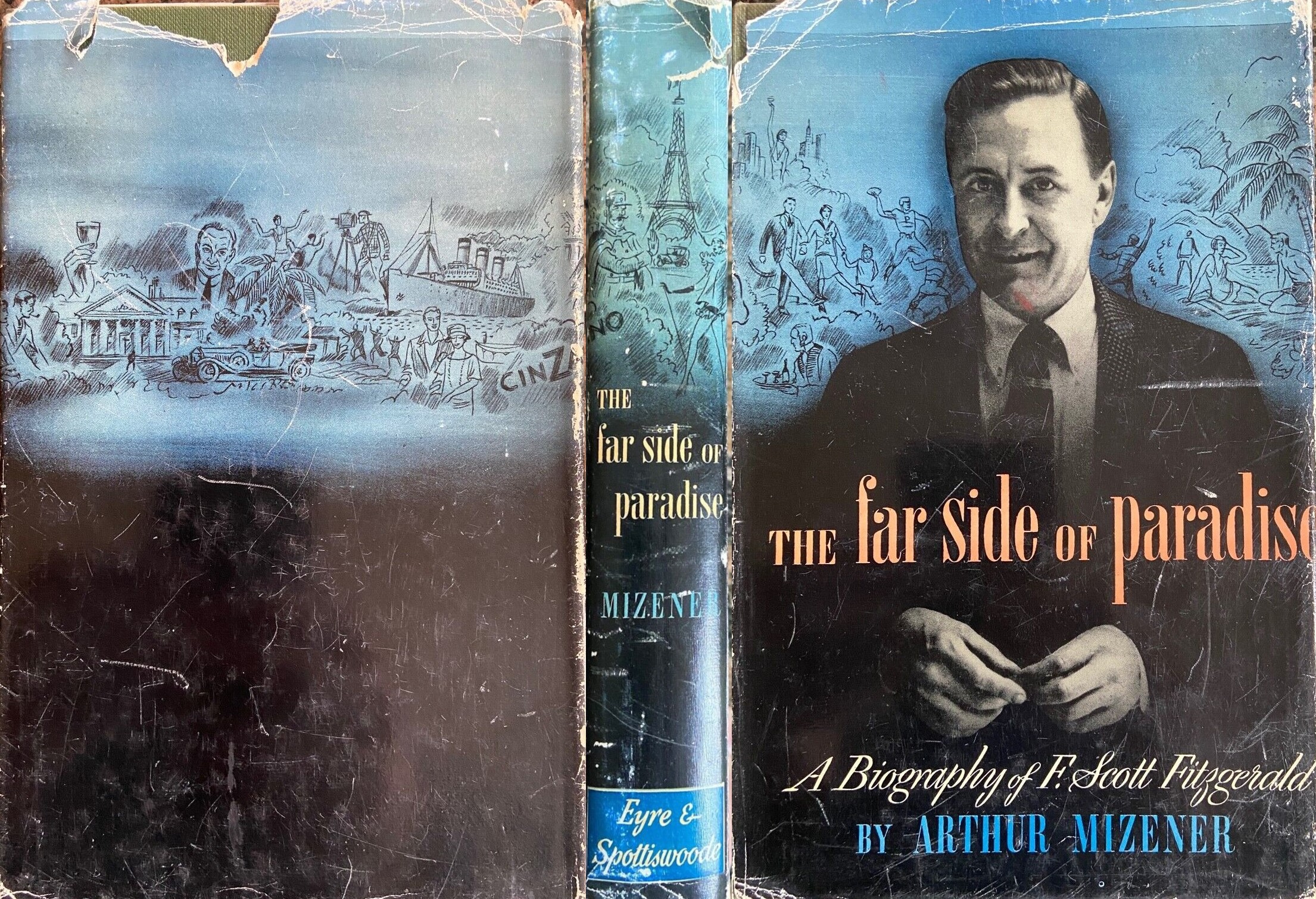

The Far Side of Paradise: A Biography Of F. Scott Fitzgerald

by Arthur Mizener

Chapter IV

When Fitzgerald met her Zelda Sayre was just eighteen, a beautiful girl with marvelous golden hair and that air of innocent assurance attractive Southern girls have. The Sayres were an undistinguished but solid and respectable Southern family; Zelda’s father had become a Judge of the City Court of Montgomery in his early thirties and was later appointed to the Supreme Court of Alabama, on which he served for thirty years. His children were brought up quietly and conservatively in what was the small-town Southern society of Montgomery (Montgomery was then a town of about 40,000). As a girl Zelda often resented her father; he was aloof, Olympian, abstractly just. She baited him to try to destroy his reserve and sometimes succeeded: the first time Fitzgerald dined at the Sayres Zelda drove Judge Sayre into a rage Fitzgerald never forgot. But these successes against the “older generation” were rare. Usually Judge Sayre was calm and certain; if he often seemed to Zelda inhumanly perfect, he provided for her a solid assurance of how things ought to be done which was always there to return to, however often she took small moral flights of her own. Later the heroine of Zelda’s novel, Save Me the Waltz, was to say that she “didn’t know how to go about asking the Judge to pay the taxi [when he visited them in New York]—she hadn’t been absolutely sure of how to go about anything since her marriage had precluded the Judge’s resented direction.” (I have assumed that Zelda's novel can be trusted to reveal her understanding of her own situation. It is clearly autobiographical, as Fitzgerald said publicly in 1932. His correspondence with Perkins shows that it was so literally autobiographical that even Fitzgerald balked and insisted on Zelda's rewriting the whole central passage. Innumerable small details indicate how much the book depends on fact: the room David and Alabama have for their honeymoon at the Biltmore is the one the Fitzgeralds had for theirs, 2109 (p. 54); the incident of the aviator's falling from his plane (pp. 42-43) occurred just as Zelda describes it (Fitzgerald used the same incident in 'The Last of the Belles'); Bonnie's blue ski suit was Scottie's and the Kodak snaps still exist (p. 232).

With the Judge’s solid convictions always in the background to support her, and with her own beauty to give her confidence, she found it possible to do, quite simply, without hesitation or self-consciousness, whatever came into her head. From the time she was a young girl she seems to have thought of herself as “two simple people at once, one who wants to have a law to itself and the other who wants to keep all the nice old things and be loved and safe and protected.” Until her marriage she could be both these people at once without serious strain, and the result was that she quickly became a famous figure in the community, a girl with innumerable daring and unconventional exploits to her credit who had already left “the more or less sophisticated beaux and belles of Atlanta… gasping for air when she struck the town.”

All this was a preparation for wartime Montgomery. With the coming of war, Camp Sheridan and Camp Taylor filled up with officers from all over the country and from what was for those times—and perhaps especially for Montgomery—a startling range of social classes. Overnight the social life of Montgomery took on an excitement, a feeling that anything was possible, which made every date a poignant moment of limitless romantic possibilities. It only added to the excitement that you never knew whether the handsome officer who cut in at the Country Club dance was a streetcar conductor, like the Earl Schoen of Fitzgerald’s story, “The Last of the Belles,” or a Harvard man of distinguished Boston ancestry, like Bill Knowles. The new ideas about manners which were developing all over the country at the time found their perfect occasion in wartime Montgomery. And Zelda—or at least the Zelda who wanted to be a law to herself—was the ideal heroine for this world; she was beautiful and witty, she was just seventeen, and there was nothing she did not dare do.

She took this larger and much more unstable world in her stride and quickly became its central figure. So regularly did flyers from Camp Taylor stunt over her house that it became necessary for the commanding officer to issue an order specifically forbidding this kind of courtship of Miss Sayre. Something of the attitude with which she met experience at this time can be seen in her later “Eulogy of the Flapper”:

How can a girl say again, “I do not want to be respectable because respectable girls are not attractive,” and how can she again so wisely arrive at the knowledge that “boys do dance most with the girls they kiss most,” and that “men will marry the girls they could kiss before they had asked papa?” Perceiving these things, the Flapper awoke from her lethargy of sub-deb-ism, bobbed her hair, put on her choicest pair of earrings and a great deal of audacity and rouge and went into the battle. She flirted because it was fun to flirt and wore a one-piece bathing suit because she had a good figure, she covered her face with paint and powder because she didn’t need it and she refused to be bored chiefly because she wasn’t boring. She was conscious that the things she did were the things she had always wanted to do.

Zelda’s extreme popularity and the competitive situation it created were an initial attraction to Fitzgerald. Like the Princess in the fairy story, though she did not have to be awakened with a kiss when he reached her side, she was barricaded and remote behind her host of admirers, a challenge to the unregarded younger son who was determined to marry the Princess and be a success. Moreover, Zelda’s habit of doing without hesitation “the things she had always wanted to do” appealed to something deep in Fitzgerald, to his conviction that “if you don’t know much—well, nobody else knows much more. And nobody knows half as much about your own interests as you know”; this side of paradise there’s little comfort in the wise.

So, because she attracted him enormously, because she was desired by many, because she seemed to feel exactly as he did—and to have far more courage to do what she felt—Fitzgerald fell in love with her. And as with every important act of his life, he made out of falling in love with her an act of identification and dedication. Like Gatsby, “he took [her] one still… night… [and] found that he had committed himself…. He felt married to her, that was all.” He was head over heels in love, by turns jealous, charmed, ecstatic.

Lolling down on the edge of time

Where the flower months fade as the days move over,

Days that are long like lazy rhyme

Nights that are pale with the moon and the clover,

Summer there is a dream of summer

Rich with dusks for a lover’s food—

Who is the harlequin, who is the mummer,

You or time or the multitude?

Still does your hair’s gold light the ground

And dazzle the blind till their old ghosts rise?…

Part of a song, a remembered glory…

Kisses, a lazy street—and night.

Zelda too was in love. “There seemed to be some heavenly support beneath his shoulder blades that lifted his feet from the ground,” she remembered when she wrote her novel, “as if he secretly enjoyed the ability to fly but was walking as a compromise to convention…. The pressure of masculine beauty equilibrated for twenty-two years had made his movements conscious and economized as the steps of a savage transporting a heavy load of rocks on his head.” She was fascinated by his extravagant gestures, such as his carving on the doorpost of the country club (instead of on a tree) a legend in which his name bulked much larger than hers (“David, David, David, Knight, Knight, Knight, and Miss Alabama Nobody” is the version she gives in her novel, Save Me the Waltz). But she was also determined to dominate the relation. The Saturday night after their first meeting, again at the country club, she suddenly dragged her escort into a lighted telephone booth and started kissing him passionately. When she stopped abruptly he said, “What’s the idea of this outburst?” and Zelda said, “Oh, Scott was coming and I wanted to make him jealous.” Most of all, perhaps, she was fascinated by the assurance with which he predicted his future fame, for like Sally Carrol of “The Ice Palace,” who is a portrait of her, she “want[ed] to live where things happen on a big scale.” (Of the writing of 'The Ice Palace,' Fitzgerald once said: 'The ... idea grew out of a conversation with a girl in St. Paul. ... We were riding home from a moving picture show late one November night [1919]. 'Here comes winter,' she said, as a scattering of confetti-like snow blew along the street. I thought immediately of the winters I had known there, their bleakness and dreariness and seemingly endless length. ... At the end of two weeks I was in Montgomery, Alabama, and while out walking with a girl I wandered into a graveyard. She told me I would never understand how she felt about the Confederate graves, and I told her I understood so well that I could put it on paper. Next day on my way back to St. Paul it came to me that it was all one story ...' ('Contemporary Writers and Their Work: F. Scott Fitzgerald,' Clipping in Album I)

In her way she was as ambitious as he was; it made for certain difficulties. Though she was in love with him, she did not, for all her yielding, commit herself as he did. She was ,not perfectly sure. “… except for the sexual recklessness,” Fitzgerald remembered with his remarkable clarity long afterwards, “Zelda was cagey about throwing in her lot with me before I was a money-maker, and I think by temperament she was the most reckless of all [the women he had known]. She was young and in a period when any exploiter or middle-man seemed a better risk than a worker in the arts.” Zelda wanted, just as Fitzgerald did, a luxury and largeness beyond anything her world provided and she had a certain, almost childlike shrewdness in pursuing it.

At the end of October the advance detachment of the Ninth Division got its overseas orders and early in November they arrived at Camp Mills, Long Island. At one point during their stay they even entrained for Quebec but were pulled off the train again and told their departure would be postponed. (Fitzgerald liked to remember marching onto a transport, steel helmet slung at his side, but that was dramatic license.) While they waited on Long Island there were a great many parties in New York; Fitzgerald as. usual provided a good deal of the fun and some of the serious trouble. He rode a cab horse through Times Square to the delight of his friends in the cab and, on another occasion, started turning cartwheels in Bustanoby’s, eventually landing in the ladies’ room.

On another occasion he borrowed a friend’s room at theAstor on the plea that he was broke and had no place to go, and then managed to get himself and a girl from Princeton caught there, completely naked, by the house detective. After considerable negotiation Fitzgerald offered the detective a hundred dollars to let them go and when the detective accepted, thrust a tightly folded bill into the detective’s hand and fled with the girl. Too late the detective found himself with a one-dollar bill in his hand, which did not make things any easier for the friend from whom Fitzgerald had borrowed the room when the detective finally caught up with him. Fitzgerald was saved from arrest by the New York police only by his commanding officer’s putting him under military arrest at Camp Mills. But when the unit entrained for Montgomery a few days later, Fitzgerald had disappeared. One of his friends told the commanding officer he thought Fitzgerald had gone to Princeton and Washington, and, in fact, when the train stopped at Washington, there was Fitzgerald sitting on the next track in the classic pose, a girl on either side of him and a bottle in his hand. Fitzgerald had an elaborate imaginary story about this occasion according to which he had gone into the Knickerbocker and got very drunk, and when he discovered his unit had left Camp Mills, had gone to the railroad people at Pennsylvania Station, told them he had confidential papers for President Wilson, and persuaded them to provide him a special locomotive to take him to Washington. He appears to have told this story first - for the sheer fun of it, without expecting to be believed - to his fellow officers when he rejoined his unit in Washington; he continued to tell it all his life (see, for example, Michael Mok, 'The Other Side of Paradise,' New York Post, September 25, 1936)

“I think,” said one of Fitzgerald’s friends of this time, “Scott abused the kindness and friendship of nearly everyone, but at that time, one could not help liking him very much.” Here is the first clear display of the pattern of behavior that was to continue throughout Fitzgerald’s life, the wild conduct and the total lack of consideration for its consequences either for himself or others alternating with the sober sensitivity and considerateness that made it impossible for people not to be very fond of him. It makes it clear that from the beginning Fitzgerald had almost no resistance to alcohol. “Like many others who got the name of being drunkards,” as Louis Bromfield, who knew him later, put it, “[Scott] simply couldn’t drink. One cocktail and he was off. It seemed to affect him as much as five or six drinks affected Hemingway or myself. Immediately he was out of control and there was only one end… that he became thoroughly drunk, and like many Irishmen, when he became drunk he usuallybecame very disagreeable and rude and quarrelsome, as if all his resentments were released at once.” By the time Bromfield knew him, there were serious resentments to be released, but from the beginning Fitzgerald acted out his fantasies in a most astonishingly literal way when he was drunk.

Back at Camp Sheridan he was made aide-de-camp to the commander, General A. J. Ryan (Fitzgerald liked to say afterwards that he spent the war as 'the army's worst aide-de-camp' ('Early Success,' The Crack-Up, edited by Edmund Wilson, New Directions, 1945, p. 85). But the order appointing him General Ryan's aide-de-camp is dated December 6, 1918, so he served in that capacity only two months out of the fourteen he was in the army.). All through December and January he and Zelda walked in the woods together, went to the vaudeville at the Grand Theatre and sat in the back so they could hold hands, “gazed at each other soberly through the chorus of ‘How Can You Tell!’” when they saw Hitchy-Koo, danced, and swam in the moonlight. Fitzgerald called her so often that he remembered the Sayres’ telephone number all his life. Still, Zelda was not easy to win. She let him read her diary (eventually he used parts of it in This Side of Paradise and The Beautiful and Damned; like all she wrote it was brilliant, amateur work); she let him spend Christmas day with her in a charmed anticipation of domesticity. But at the same time she continued to go to all the local dances with others, and to attend proms at Auburn and Georgia Tech. On these occasions Fitzgerald would get drunk, and later they would quarrel and Zelda would question whether he was ever going to make enough money for them to marry and live as she wished to. She “held him firmly at bay” (the phrase is Fitzgerald’s own - when Fitzgerald was writing The Count of Darkness he jotted down a note about the heroine: '... after yielding she holds Phillipe at bay like Zelda me in 1917 [sic: 1918].').

On February 14, 1919, his discharge came through. For a long time he had been thinking of that fine man’s world he had seen Edmund Wilson enjoying in Eighth Street in the spring of 1917, and he and Bishop had been planning to set themselves up in a similar apartment in New York. Before the armistice, he had written Bishop suggesting the idea (Bishop was overseas) and Bishop had replied:

Will you honestly take a garret (it may be a basement but garret sounds better) with me somewhere near Washington Square? Shall we go wandering down to Princetonon fragrant nights in May?… We’ll have a drunk—what if the bars are closed. I am bringing back a trunk locker. We’ll wander about New York… then go down to Princeton, climb the stairs of Witherspoon and bellow down the Nass. We’ll chant Keats along the leafy dusk of Boudinot Street and come back to talk the night away.

But now there was the serious business of making a fortune to be attended to promptly, for Zelda was not going to wait forever. When he reached New York on February 19 he wired her with anxious enthusiasm: darling heart ambition ENTHUSIASM AND CONFIDENCE I DECLARE EVERYTHING GLORIOUS THIS WORLD IS A GAME AND WHILE I FEEL SURE OF YOU[R] LOVE EVERYTHING IS POSSIBLE I AM IN THE LAND OF AMBITION and success. … In the land of ambition and success he began tramping the streets in search of a job. His notion was to “trail murderers by day and write short stories by night,” so he canvassed every newspaper in town, carrying the scores of his Triangle shows under his arm as evidence of his talent. “The office boys,” he said later, “were not impressed.”18 He finally settled for a job with the Barron Collier agency writing advertising slogans, mainly for streetcar cards. His biggest success, however, was a slogan for a steam laundry in Muscatine, Iowa: “We Keep You Clean in Muscatine.” “It’s perhaps a bit imaginative,” he remembered the boss’s saying, “but still it’s plain that there’s a future for you in this business.”

He settled into a room at 200 Claremont Avenue—“one room in a high, horrible apartment-house in the middle of nowhere”—to live temporarily on his ninety dollars a month and to make his fame and fortune writing stories at night. He produced nineteen of them between April and June, but “no one bought them, no one sent personal letters. I had one hundred and twenty-two rejection slips pinned in a frieze about my room.” In June he sold a story to the Smart Set, which George Jean Nathan and H. L. Mencken were making the liveliest magazine in America. But the story was “Babes in the Woods,” which he had written more than two years earlier for the Lit. He used the thirty dollars it brought him to buy a pair of white flannels; he still had them, stored away like a bartender’s first dollar, in 1934. Meanwhile Zelda was becoming more and more what she called, in an ominous circumlocution, “nervous.” “He knew what ‘nervous’ meant—that she was emotionally depressed, that the prospect of marrying into a life of poverty and struggle was putting too much strain upon her love.” Fame and fortune did not seem to be materializing on schedule for Fitzgerald, and Zelda was fretting her time away in Montgomery wondering if she ought not to marry one of her more eligible and financially better equipped admirers.

It was all much too clear to Fitzgerald. In March he had sent her an engagement ring which must have been pathetically modest under the circumstances, and twice during the spring Zelda’s nervousness reached a point where frequent telegrams no longer calmed her and Fitzgerald had to go to Montgomery to see her. “I used to wonder,” he noted bitterly, “why they locked Princesses in towers.” Now that solution of the difficulty struck him as so admirable that Zelda had to write him: “Scott, you’ve been so sweet about writing—but I’m so damned tired of being told you ‘used to wonder why they kept princesses in towers’—you’ve written that verbatim in your last six letters! “

… in a haze of anxiety and unhappiness [he recalled afterwards] I passed the four most impressionable months of my life. … As I hovered ghost-like in the Plaza Red Room of a Saturday afternoon, or went to lush and liquid garden parties in the East Sixties or tippled with Princetonians in the Biltmore Bar I was haunted always by my other life—my drab room in the Bronx, my square foot of the subway, my fixation upon the day’s letter from Alabama—would it come and what would it say?—my shabby suits, my poverty, and love. … I was a failure—mediocre at advertising and unable to get started as a writer.

The fact that “the returning troops marched up Fifth Avenue and girls were instinctively drawn East and North toward them” so that you felt “this was the greatest nation and there was gala in the air” only made matters worse. When it was all over, he sat down and summed it up in “May Day,” the first of those beautifully balanced impressionistic stories he was to write from time to time all his life. “May Day” covers the whole range of his experience, from his most personal and private feelings, through his awareness of the mixed lives of farm boys, waiters, party girls, prom trotters, and college boys, to his acute sense of the times, of the pride and prosperity and repression of post-war America. The Jazz Age, he remarked much later, “began about the time of the May Day riots in 1919.” Gordon Sterrett, with his frayed shirt cuffs and his poverty, his inability to get started as a cartoonist and his alcoholic deterioration, is Fitzgerald’s exaggeratedly condemnatory portrait of himself. Gordon’s suicide after Philip Dean refuses to lend him money reflects Fitzgerald’s moments of acute despair over his financial situation. Gordon is the story’s projection of Fitzgerald’s private consciousness, but the story as a whole covers the full complex of experience at a significant moment in the history of Fitzgerald’s time.

Instead of committing suicide like Gordon Sterrett, Fitzgerald escaped into innumerable parties with his college friends, some of them full of the delight and extravagance of undergraduate revelry, all of them, no doubt, haunted for him by his other life, as Gordon Sterrett’s parties with his old college friends are haunted. The most colorful of these parties grew out of the interfraternity dance at Delmonico’s in May, 1919, which provided the material for Mr. In and Mr. Out in “May Day.” It began with Fitzgerald sitting quietly in the Fifty-Ninth-Street Childs carefully mixing hash, dropped eggs, and catsup in his companion’s derby. When he was interrupted he insisted on climbing on a table and making a speech, and after he had been dragged from the table and out of Childs he wanted to explain to everybody that the façade of the buildings around Columbus Circle does not really curve; it only seemed to because he was drunk. Later he and a college friend, Porter Gillespie, returned to the party at Delmonico’s and played their game of Mr. In and Mr. Out. Well into the next morning they breakfasted on shredded wheat and champagne, carrying the empty bottles carefully out of the hotel and smashing them on the curb for the benefit of the churchgoers along Fifth Avenue.

In June Zelda sent him a print of a picture he had paid to have taken which she had inscribed affectionately to Bobby Jones. This must have been another of her calculated maneuvers, like the telephone-booth business at the country club, since Mr. Jones has said that he never even had a date with Zelda. Nevertheless, when Fitzgerald responded to this inscribed photograph with an outburst of jealousy, she again became so “nervous” that he felt he had to go to Montgomery to see her. But this time it did not work; Zelda had had enough of the strain of an engagementwhich every day looked less as if it were going to lead to a marriage. She told him flatly she was not prepared to go on. Fitzgerald took the situation very badly. “He seized her in his arms and tried literally to kiss her into marrying him at once,” he wrote when he described his conduct in “‘The Sensible Thing.’” “When this failed, he broke into a long monologue of self-pity, and ceased only when he saw that he was making himself despicable in her sight. He threatened to leave when he had no intention of leaving, and refused to go when she told him that, after all, it was best that he should.” When Zelda finally saw him off at the station, he climbed into a Pullmanand then sneaked through into the daycoach, which was all he could afford for the trip back to New York. It was a desperate irony for the man who had just been trying to persuade his girl he was rich enough for her. “He had met [her] when she was seventeen,” he wrote when he came to sum up this experience, “possessed her young heart all through her first season… and then lost her, slowly, tragically, uselessly, because he had no money and could make no money; because, with all the energy and good will in the world, he could not find himself; because, loving him still, [she] had lost faith and begun to see him as something pathetic, futile and shabby, outside the great, shining stream of life toward which she was inevitably drawn.” This was Zelda’s attitude as Fitzgerald understood it, an attitude with which he sympathized, which he felt to be unavoidable in the kind of girl he admired. She was “inevitably drawn” toward ”the … stream of life,” a stream with such a high concentration of money in it that it shone.

He came back to New York and went on an epic three-weeks’ drunk which provided him with one of the best scenes in This Side of Paradise. Physical exhaustion and the advent of prohibition put an end to this cure, but it had, as he said of Amory’s drunk, “done its business; he was over the first flush of pain.” When he sat down to take stock of his situation, he decided he might as well try his hand once more at a novel. “The idea of writing [This Side of Paradise]” he said shortly afterwards, “occurred to me on the first day of last July. It was a sort of substitute form of dissipation.” But the remarkably optimistic young man had not, in spite of his recent blow, altogether given up his dream of success; he took up the idea of writing his novel over again in part because he still hoped to produce a best seller, win Zelda back, and become famous and admired.

He quit his advertising job with relief and, on July 4, left for St. Paul, having made an arrangement with his motherthat he could have his old room on the third floor. There he settled down to rewrite The Romantic Egotist according to a schedule which he had pinned to the curtain before his desk. Not even an appeal from Edmund Wilson could interrupt his work. Wilson and Stanley Dell were trying to put together a volume of realistic war stories, and Wilson wrote Fitzgerald an amusing and penetrating request for a contribution:

No Saturday Evening Post stuff, understand! Let us have the Army, as it is,—Come now! clear your mind of cant! brace up your artistic conscience, which was always the weakest part of your talent! forget for a moment the phosphorescences of the decaying Church of Rome! Banish whatever sentimentalities may still cling about you from college! Concentrate in one short story a world of tragedy, comedy, irony and beauty!!!—I await your manuscript with impatience.

Fitzgerald replied: “I have just finished the story for your book. It’s not written yet.”

It never was; he stuck to his schedule for the novel until it was finished. He revised carefully every scene he retained from The Romantic Egotist and added a good many new ones, including practically all of Book Two of This Side of Paradise (Except, of course, the Eleanor episode (see pp. 46-47 above). Much of the new material was doubtless not written in these two months, however. Apart from 'The Debutante' (THIS SIDE OF PARADISE, pp. 179-93), 'Babes in the Woods' (THIS SIDE OF PARADISE, pp. 73-78), 'On a Play Twice Seen' (THIS SIDE OF PARADISE, p. 147), and 'Princeton, the Last Day' (THIS SIDE OF PARADISE, p. 168), which had appeared much earlier in the Nassau Lit and the Smart Set Fitzgerald himself noted as one of the sources of THIS SIDE OF PARADISE 'destroyed stories of 1919' (Ledger, p. 3). These would be some of the stories that were written and rejected while he was a copywriter.) He worked hard through two hot summer months in his third-floor front room at 599 Summit, with the result that by the end of July he was able to write Maxwell Perkins at Scribner’s that he had completed the first draft of the revision; “This is a definite attempt at a big novel,” he wrote, “and I really believe I have hit it…” By the end of August he had been through the whole manuscript again. On September 3 he wrapped it up, hugged it to him, and with his invariable feeling for the drama of an occasion, cried to his friend Tubby Washington, “Tubby! Maybe this is it!” The manuscript seemed to him too precious to trust to the mails, and he persuaded an acquaintance, Mr. Thomas Daniels, to carry it to Scribner’s.

Meanwhile he had, of necessity, been living very quietly. He spent occasional evenings down the block at 513 with John Briggs (later the headmaster of St. Paul Academy) and Donald Ogden Stewart, two young men who were as full of modern literature as he; they would discuss the latest books and argue over what Fitzgerald was doing in This Side of Paradise; or they would wander out to see Father Joe Barron, an intelligent and sympathetic priest, and argue with him into the small hours about such things as the ascetic ideals of the thirteenth century. Stewart’s elaborate jokes—his obviously faked ventriloquist act and his parody illustrated lectures—never failed to delight Fitzgerald. But most nights he walked quietly down to the corner drugstore and let Tubby buy him a coke and cigarettes. The cokes distressed his Aunt Annabel: she was sure he was ruining his health. He lived thus off Tubby because his family, angry because he refused to enter on a proper business career, would not give him pocket money.

It was a misery to them, too, that he hardly pretended to be a good Catholic any more. He was never very devout, though like most people he had moments as he was growing up when his imagination was appealed to by religion (“Became desperately Holy,” he noted of himself at fourteen), and occasionally he was attracted by a colorful piece of Catholic history and the sense of a great and socially impressive tradition which it gave him. Still he had been brought up a Catholic, with all that means in the way of habitual convictions. If it is too simple to say, as one of his contemporaries did, that “when Scott ceased to go to mass he began to drink,” it is true that his unfaltering sense of life—and especially his own life—as a dramatic conflict between good and evil was cultivated, if not determined, by his early training. As he wrote Wilson at this time: “I am ashamed to say that myCatholicism is scarcely more than a memory—no that’s wrong it’s more than that; at any rate I go not to church nor mumble stray nothings over chrystaline beads.” It takes a sense of sin which lies far deeper than any nominal commitment to a doctrine to be as powerfully affected by immoral conduct, especially his own immoral conduct, as Fitzgerald Was. “Poor Scott,” as one shrewd friend remarked, “he never really enjoyed his dissipation because he disapproved intensely of himself all the time it was going on.” At the same time, of course, the very significance thus lent to dissipation made it seem fascinating and important to him, so that he sometimes appeared to have almost a compulsion to shock himself.

However damned this attitude may be, it could exist only in a man whose basic feeling for experience was a religious one. This was hardly clear to his family. What they did see was what he was at no pains to conceal. “There is no use concealing the fact,” he wrote Shane Leslie a year later, “that my reaction a year ago last June [i.e., June, 1919] to apparent failure in every direction did carry me rather away from the church. My ideas now are in such wild riot that I would flatter myself did I claim even the clarity of agnostisism.” That last sentence is polite evasion, for at about the same time he assured President Hibben in the letter he wrote him about This Side of Paradise that “my view of life, President Hibben, is the view of [the] Theodore Dreisers and Joseph Conrads—that life is too strong and remorseless for the sons of men.” Such talk shocked and angered his family.

Their disapproval of his opinions was not decreased when a St. Paul firm, Griggs Cooper, offered him the position of advertising manager at a very good salary and he refused it. Mr. Milton Griggs clearly remembers the occasion of this offer but not the exact salary, but Fitzgerald's friends remember it as impressive. This refusal shows how much he was prepared to stake on This Side of Paradise and how intolerable, to his imagination as well as Zelda’s, merely moderate success was. Not even the possibility that the Griggs Cooper position might temptZelda moved him—or perhaps he knew, from his own feelings, that in the long run it would not provide a life that would satisfy her.

While he waited to hear from Scribner’s he did, however, take a job. His old friend Larry Boardman, who had worked up to a supervisory position in the Northern Pacific carbarn, got it for him. He told Fitzgerald to report in old clothes. Fitzgerald arrived in dirty white flannels, polo shirt, sweatshirt, and a blue cap, and complained to Boardman that he did not seem to be able to make conversation with the men. Eventually he caught on and bought a pair of overalls and learned not to offend the foreman by sitting down when he hammered nails. After a few days, however, he decided he was not cut out for this kind of work and quit. The day he did so, his new, four-dollar overalls were stolen, a misfortune which wiped out practically everything he had earned. Luckily he did not have to wait very long to hear from Scribner’s; this time Perkins was enthusiastic about the book and, with the help of Charles Scribner, Jr., persuaded the elder Mr. Scribner to accept it. He wrote Fitzgerald special delivery on September 16:

I am very glad, personally to be able to write you that we are all for publishing your book, “This Side of Paradise.” Viewing it as the same book that was here before, which in a sense it is, though… extended further, I think that you have improved it enormously. As the first manuscript did, it abounds in energy and life and it seems to me to be in much better proportion…. The book is so different that it is hard to prophesy how it will sell, but we are all for taking a chance and supporting it with vigor.

Fitzgerald was overwhelmed. “Of course I was delighted to get your letter,” he wrote Perkins two days later, “and I’ve been in a sort of trance all day….” He was so excited that day that he ran up and down Summit Avenue stopping cars and telling all his friends and a good many mere acquaintances that his book had been accepted. His battered morale revived and he was once more full of confidence. The possibility that the novel might not shake the world but, like most first novels, slip quietly into the great silence simply never occurred to him. A month or so later, when he called on Scribner’s in New York, he assured them he would be quite satisfied with a sale of 20,000 copies in the first year. [The book actually did far better than that. Published March 26, 1920, it had sold 32,786 copies by November 8, 1920, 39,786 by February 1, 1921. Before the original sale died down, about the middle of 1923, it had sold better than 50,000 copies. A cheap reprint sold another 20,000 copies during the next year. “The book didn’t make me as rich as I thought it would nor as you would suspect from the vogue and the way it was talked about,” Rascoe reported Fitzgerald as saying. “… its actual sale wasn’t more than 30,000 copies the first year.” (We Were Interrupted, p. 20.) Despite the inaccurate figure, this probably represents Fitzgerald’s feeling. For a famous book, This Side of Paradise did not sell very well.]

From the very beginning he kept at Perkins for immediate publication; his reasons for this impossible request are revealing:

… one thing I cannot relinquish without a slight struggle. Would it be utterly impossible for you to publish the book Xmas—or say by February? I have so many things dependent on its success—including of course a girl—not that I expect it to make me a fortune but it will have a psychological effect on me and all my surroundings…. I’m in that stage where every month counts frantically and seems a cudgel in a fight for happiness against time.

Not that Zelda was abnormally hardhearted and determined about the fortune; Fitzgerald was ready to marry even with poor financial prospects, but he understood and sympathized with Zelda’s attitude. It is worth observing that the position ascribed to her in his letter to Perkins is Fitzgerald’s conception of her attitude: the letter was written only two daysafter the novel had been accepted, before Zelda could even have heard the news, to say nothing of responding to it. “I can’t,” says Rosalind to Amory, “be shut away from the trees and flowers, cooped up in a little flat, waiting for you. You’d hate me in a narrow atmosphere. I’d make you hate me. … I wouldn’t be the Rosalind you love. … I like sunshine and pretty things and cheerfulness—and I dread responsibility. I don’t want to think about pots and kitchens and brooms. I want to worry whether my legs will get slick and brown when I swim in the summer.” Part of what Fitzgerald loved very much in Zelda was the integrity of her belief in her rights as a beauty to have pretty things and to let others take the responsibility. Long after he remarked that this being “one of the eternal children of this world” was “a thing people will stand until they realize the awful toll exacted from others.” How soon he realized what this toll was is shown by the portrait of Luella Hemple in “The Adjuster” (written in December, 1924). “We make an agreement with children,” says Doctor Moon, “that they can sit in the audience without helping to make the play, but if they still sit in the audience after they’re grown, somebody’s got to work double time for them, so that they can enjoy the light and glitter of the world.” This is Fitzgerald’s view of Zelda, no doubt true as far as it goes, but, for all its sympathy, a partial view. We have no similar record of Zelda’s view of his shortcomings, and as his favorite author, Samuel Butler, remarked in his “Apology for the Devil,” “It must be remembered that we have heard only one side of the case. God has written all the books.” In any event, the appeal of Zelda’s imperiousness was at this time much stronger than its power to disturb him, because its demands on life were so very like his own.

The bubbling excitement in which he lived during the period immediately after the acceptance of This Side of Paradise can be seen in the letter he wrote his childhoodfriend, Alida Bigelow, then a student at Smith, a few days after the news reached him. The letter is headed: “1st Epistle of St. Scott to the Smithsonian, Chapter the I, Verses the I to the last,” and under the date there is a piece of doggerel which begins:

What’s a date!

Mr. Fate

Can’t berate

Mr. Scott.

He is not

Marking time…

Time was not, after all, getting the better of him; he was sure now that he was showing life he was a good enough man to dominate it. The body of the letter then goes on to assert a series of melancholy attitudes with such ebullience as to deny them in the very act of stating them.

Most beautiful, rather-too-virtuous-but-entirely-enchanting

Alida:

Scribner’s has accepted my book. Ain’t I smart! … In a few days I’ll have lived one score and three days in this vale of tears. On I plod—always bored often drunk, doing no penance for my faults—rather do I become more tolerant of myself from day to day, hardening my chrystal heart with blasphemous humor and shunning only toothpicks, pathos, and poverty as being the three unforgivable things in life….

I am frightfully unhappy, look like the devil, will be famous within 1 12 month and, I hope, dead within 2.

Hoping you are the same

I am

With Excruciating respect

F. Scott Fitzgerald

P.S. If you wish you may auction off this letter to the gurlsof your collidge—on condition that the proceeds go to the Society for the drownding of Armenian Airdales

Bla!

F. S. F.

On the crest of this wave of enthusiasm he began to write like mad; he got some work done on a new novel which he tentatively entitled The Demon Lover (“A very ambitious novel… which will probably take a year”), but mostly he wrote short stories. Between September and December he produced nine stories—one of them was written in a single evening—and polished up another one that had been written in the spring and rejected everywhere. The new stories were “Dalyrimple Goes Wrong” and “The Smilers,” written in September; “Porcelain and Pink,” “Benediction,” and “The Cut-Glass Bowl,” written in October; “Head and Shoulders” and “Mr. Icky,” written in November; “Myra Meets His Family” and “The Ice Palace,” written in December. The old story was “The Four Fists”, written in one evening, it was a story Fitzgerald had always particularly disliked: “I've always hated and been ashamed of that damned story ‘The Four Fists,’” he wrote Perkins. “Not that it is any cheaper than The Off Shore Pirate because it isn't but simply because it's a plant, a moral tale and utterly lacks vitality” (letter to John Grier Hibben, June 3, 1920; to Maxwell Perkins, ca. December 1, 1921). He was still anxious to demonstrate that he was a money-maker, and the quickest way to swing a cudgel in his “fight for happiness against time” was to produce salable short stories in impressive quantity. During October he managed to make $215—mostly from The Smart Set—and to pay off his “terrible small debts.” Even small debts like these were terrible to him. One of the most persistent manifestations of his divided nature is the way he was always in debt, often seriously so, and yet never ceased to be deeply shocked by the fact.

The Smart Set’s $215, together with $300 that Bridges, the editor of Scribner’s Magazine, paid him on November 1 for two stories, made him a man of means and he felt ready to see Zelda again. In the middle of November, therefore, he returned to Montgomery in subdued triumph. He and Zelda walked in the Confederate cemetery and sat again on the remembered couch in the Sayres’ living room. Everything was the same; it was the renewal he had dreamed of so long. Only everything was not the same. For one thing, “I was a professional and my enchantment with certain things that she felt and said was already paced by an anxiety to set them down in a story—it was called The Ice Palace…“ For another thing, the magic was gone. As he wrote afterward in “‘The Sensible Thing’“:

There was nothing changed—only everything was changed…. He saw [the sitting room] was only a room, and not the enchanted chamber where he had passed those poignant hours. He sat in a chair, amazed to find it a chair, realizing that his imagination had distorted and colored all these simple familiar things…. He knew that that boy of fifteen months before had had something, a trust, a warmth that was gone forever. The sensible thing—they had done the sensible thing. He had traded his first youth for strength and carved success out of despair. But with his youth, life had carried away the freshness of his love…. He could never recapture those lost April hours…. Well, let it pass, he thought; April is over, April is over. There are all kinds of love in the world, but never the same love twice.

These feelings were genuine but, as the title of his story suggests, less sensible than Zelda’s. “… don’t try so hard,” she wrote him, “to convince yourself that we’re very old people who’ve lost their most precious possessions…. That first abandon couldn’t last, but the things that went to make it are tremendously alive … so don’t mourn for a poor little forlorn memory….” But it was not in Fitzgerald’s nature to be sensible about his emotional investments, and Zelda knew that; she understood Fitzgerald’s divided nature quite clearly. Earlier she had written him about another problem: “I know you’ve worried—and enjoyed doing it thoroughly—and I didn’t want you to. … I know it’s depriving you of an idea that horrifies and fascinates—you’re so morbidly exaggerative…. Sort of deliberately experimental and wig…

Thus they became engaged again, informally; they would be married when Fitzgerald’s book came out. With that unconscious irony absolute accuracy often produces, Fitzgerald described the situation to Perkins by saying: “I’m almost sure I’ll get married as soon as my book is out.” With this much assurance about Zelda, he went on to New York, where Paul Reynolds, the literary agent, agreed to handle his work. Hewas assigned to the immediate care of a young man named Harold Ober, and so conscientiously did Ober handle the sales of Fitzgerald’s stories and their author’s confused and often desperate financial affairs that when he set up an agency of his own in September, 1929, there was no question about Fitzgerald’s going with him. He began auspiciously by selling “Head and Shoulders” to the Post for $400, nearly three times as much as Fitzgerald had ever been paid before. At the same time Metro made a flattering movie offer. On the strength of these successes Fitzgerald got roaring drunk and flooded his hotel by leaving the tap on in his bathroom.

He returned to St. Paul “in a thoroughly nervous alcoholic state” which did not, however, prevent his celebrating at the Christmas parties. He had now given up the ambitious writing schemes he had worked out in his enthusiasm the previous fall (In October he proposed to make a novelette to be called 'The Diary of a Literary Failure' for Scribner's Magazine out of a journal he had been keeping for over three years; he was going to write this novelette concurrently with writing 'The Demon Lover'; by the end of the year both these projects were defunct (to Robert Bridges, October 25 and December 26, 1919; the first of these is in The Letters of F. Scott Fitzgerald, edited by Andrew Turnbull, New York, 1963 , p. 140). The journal seems to have disappeared.). Instead he revised two of the old rejected stories and Reynolds promptly sold them to the Post for $1000. Then, with one of those incredible bursts of energy on which he was to come more and more to depend, he managed to turn out a mildly amusing story about a drunk who had gone to the wrong party as one end of a camel. “12,000 words,” as he wrote Perkins, “… begun eight o’clock one morning and finished at seven at night and then copied between seven and half past four and mailed at 5 in the morning.” This burst of energy gave him enough money to go to New Orleans “because I’m afraid I’m about to develop tuberculosis.” Probably he was right, for a later medical examination showed the scars of a mild attack. At the same time he was writing Perkins: “I want to start [a new book] but I don’t want to go broke in the middle and start in and have to write short stories again… for money.” He had not been able to pay for a Coca-Cola five months before, and had since made a couple of thousand dollars and could look forward to the profits of his novel, but he was a man who half consciously assumed that the necessities of life did not haveto be calculated as expenses and was thus able to look on the main portion of his income as available for “free” expenditure, with the result that, to his continual astonishment, he always lived well beyond his income.

He arrived in New Orleans in the middle of January, settled into a boarding house on Prytania Street, and started another novel; in less than a month he had given it up (The novel, called 'Darling Heart,' turned on the seduction of the heroine. It was perhaps a first and torturously indirect effort to come to imaginative terms with his seduction of Zelda, an experience he finally dealt with wholly satisfactorily in Gatsby's seduction of Daisy. For a long time he found the subject impossible to leave alone and badly embarrassed Hemingway the first time they met by bringing it up at once (see A Moveable Feast, p. 151). 'Darling Heart' was quickly dropped when there was an outburst of suppressions of daring novels and Fitzgerald told Perkins he planned to 'break up the start of my novel and sell it as three little character stories to Smart Set' (to Maxwell Perkins, February 3, 1920; The Letters of F. Scott Fitzgerald, edited by Andrew Turnbull, New York, 1963 , p. 144). The only story he sold to Smart Set at this time was 'May Day,' which was certainly never part of 'Darling Heart.' Possibly he used some of 'Darling Heart' for the story of Anthony Patch and Dorothy Raycroft (THE BEAUTIFUL AND DAMNED, NEW YORK, 1922, Book III, Chapter 1) ; that story is one of his many versions of himself and Zelda.). He did not like New Orleans. “O. Henry said this was a story town,” he said, “—but its too consciously that—just as a Hugh Walpole character is too consciously a character.” He did, however, turn out two stories which were again promptly sold to the Post. His wooing of Zelda, conducted to a considerable extent by telegram, consisted largely of reports of these sales: the Saturday evening post has just TAKEN TWO MORE STORIES PERIOD ALL MY LOVE, he would wire; or: I HAVE SOLD THE MOVIE RIGHTS OF HEAD AND SHOULDERS TO THE METRO COMPANY FOR TWENTY FIVE HUNDRED DOLLARS I LOVE YOU DEAREST GIRL. It would be hard to say whether his own delight in success or his desire to sooth any incipient “nervousness” in Zelda weighed more heavily in this curious form of wooing.

This delight in success was, in any event, only a part of his attitude toward his work, a part that was to conflict all his life with a desire to write not just profitably but well. As early as December, 1919, he had asked Harold Ober, “Is there any market at all for the cynical or pessimistic story except Smart Set or does realism bar a story from any well-paying magazine no matter how cleverly it is done?” Two years later he had reached the point of asserting that, despite his talent, he was determined to grit his teeth and make money:

I am rather discouraged—he wrote Ober—that a cheap story like The Popular Girl written in one week while the baby was being born brings $1500.00 & a genuinely imaginative thing into which I put three weeks real enthusiasm likeThe Diamond in the Sky [“The Diamond as Big as the Ritz”] brings not a thing. But, by God and Lorimer, I’m going to make a fortune yet.

This conflict was to haunt his career from beginning to end. From the time he wrote “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button” (“altogether too unusual for us to publish,” said the Post) to the time he wrote “Crazy Sunday” (which, according to the Post, “didn’t get anywhere or prove anything”), his best work was hard to sell. But it was frighteningly easy to sell his competent, mediocre, and even his bad work. He never stopped trying to write good stories, but when he became desperate for money, he found it hard to resist selling stories he was ashamed of, such as “Your Way and Mine,” of which he wrote Ober in 1926: “This is one of the lousiest stories I’ve ever written. Just terrible! … Please—and I mean this—don’t offer it to the Post. … I’d rather have $1000. for it from some obscure place than twice that and have it seen. I feel very strongly about this! “ This was the most he could afford his conscience.

Twice during January, 1920, he came up from New Orleans to Montgomery to see Zelda. The second time their engagement was put on a formal basis, and he brought a batch of Sazaracs all the way from New Orleans to celebrate the occasion. The Post had just taken four more of his stories. Again he went on to New York to complete the sale of Head and Shoulders to the movies, an event which he celebrated in two very characteristic ways. With the help of an old friend, Ruth Sturtevant, he bought Zelda an expensive feather fan; and he treated himself, like a child in a candy shop, to all the luxuries of New York ['Auction - Model 1934,' The Crack-Up, edited by Edmund Wilson, New Directions, 1945, p. 59, says the 'blue feather fan [was] paid for out of a first Saturday Evening Post story; it was an engagement present - that together with a southern girl's first corsage of orchids'; and in 'Early Success,' The Crack-Up, edited by Edmund Wilson, New Directions, 1945, p. 86, Fitzgerald says: 'I spent the thirty dollars [which he received from Smart Set for 'Babes in the Woods'] on a magenta feather fan for a girl in Alabama.' Neither of these statements is quite accurate. Fitzgerald's first Post story was sold in November; the magenta fan was sent Zelda the following February; the orchids were sent her for the occasion of the formal announcement of their engagement in March. (See Ledger, p. 174, and ZELDA SAYRE FITZGERALD's Scrapbook.) In November he had sent his sister Annabel a blue ostrich plume fan. (Mrs. Clifton Sprague to Arthur Mizener, March 23, 1959.)]. When two old friends looked him up they found him having himself bathed by two bellboys. When he finally got himself dressed, he insisted on taking them to “his” bootlegger on Lexington Avenue and buying them each a pint of Scotch. This gesture was impressive in 1920; bootleggers did not become standard equipment until several years later. At dinner-time Fitzgerald announced that he had a date. His preparations for it included fixing hundred-dollar bills in his vest pockets in such a way as to expose them prominently. Since he had been hinting that this date was a daring one, his friends felt this piece of conspicuous display was ill-timed. They finally got the bills away from him and put them in the hotel vault; they amounted to $500 or $600. He was drunk with the excitement of money.

At the same time he saw his own rise from poverty to affluence as an illustration of the terrible, meaningless power of money. It was not his nature to deduce from this understanding a conviction that society needed to be totally reconstructed; but, as he recalled in 1936 when he went back over his life trying to explain his crack-up, “the man with the jingle of money in his pocket who married the girl a year later would always cherish an abiding distrust, an animosity, toward the leisure class—not the conviction of a revolutionist but the smouldering hatred of a peasant. In the years since then I have never been able to stop wondering where my friends’ money came from, nor to stop thinking that at one time a sort of droit de seigneur might have been exercised to give one of them my girl.”

In March he went down to Princeton to stay at Cottage until Zelda came up for the wedding. There he finally realized that dream of renewing his undergraduate life which he and Bishop had shared throughout the war. He went to the Prom and did a good many other things which had been luxuries or impossibilities for him when he was an undergraduate. [Compare Dexter Green's recollections of college, especially, 'They had played [that tune] at a prom once when he could not afford the luxury of proms, and he had stood outside the gymnasium and listened.' - 'Winter Dreams']. The illusion of undergraduate days was easy to create because so many of his contemporaries were back in college from the war completing the work for their degrees. In his spare time he worked, and worked with that complete seriousness and concentration of his talent which he always seemed to be able to summon in the odd intervals of exhausting and irrelevantactivities. “Can’t work here,” he wrote Perkins from Cottage, “so have just about decided to quit work and become an ashman. Still working on that Smart Set novelette.” The Smart Set novelette was “May Day” and it was completed before he left Princeton.

On March 20 the Sayres announced the engagement and Fitzgerald sent Zelda her first orchid. They were now planning to be married as soon as possible. On March 26 This Side of Paradise was published.

Next chapter 5

Published as The Far Side Of Paradise: A Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald by Arthur Mizener (Rev. ed. - New York: Vintage Books, 1965; first edition - Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1951).