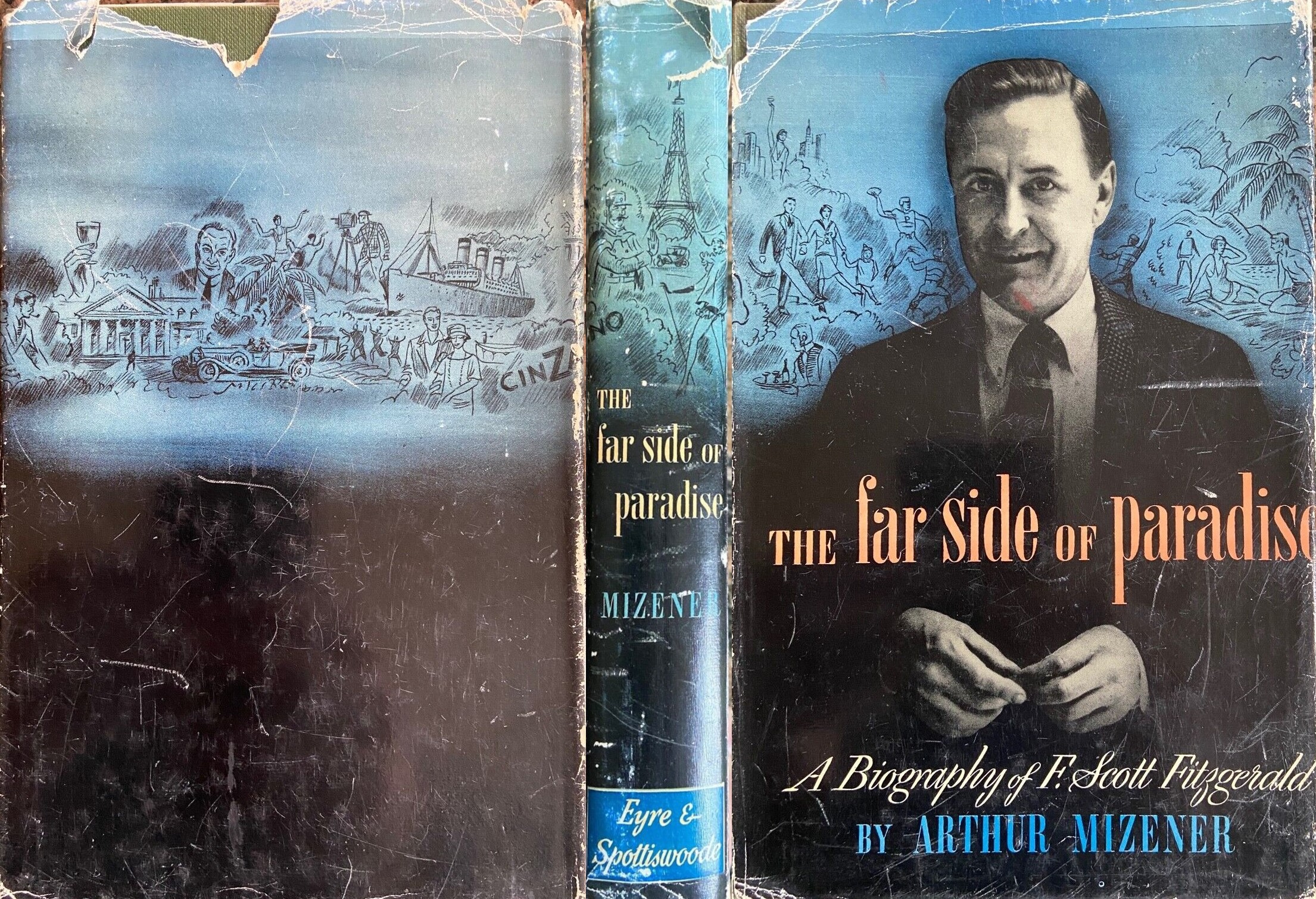

The Far Side of Paradise: A Biography Of F. Scott Fitzgerald

by Arthur Mizener

Chapter I

Fitzgerald’s lifehas, apart from its close connection with his work, a considerable interest of its own; it was a life at once representative and dramatic, at moments a charmed and beautiful success to which he and his wife, Zelda, were brilliantly equal, and at moments disastrous beyond the invention of the most macabre imagination. The moral of its history is the teasing puzzle any human history is; but the forces of flawed character and of chance are revealed in Fitzgerald’s life with remarkable fullness, both because it was a dramatic life lived with all the lack of caution which characterized Fitzgerald and because he spent his life representing what he understood of it. Just as his life illuminates his work, so his work does his life.

He was born at three-thirty in the afternoon of September 24, 1896, in a house on Laurel Avenue in St. Paul, Minnesota. He weighed ten pounds and six ounces: it was the only period in his life when he was the physical superior of his contemporaries. His father, Edward Fitzgerald, had been born in 1853 on a farm named Glenmary near Rockville in Montgomery County, Maryland, and was descended, on his mother’s side, from Scotts and Keys who had been in this country since the early seventeenth century and had regularly served in the colonial legislatures. Edward Fitzgerald’s greatgrandfather, Philip Barton Key, had been a member of theCongress under Jefferson; his aunt, Mrs. Suratt, was hanged for complicity in the murder of Lincoln. Francis Scott Key was a remote cousin of his mother. At the close of the Civil War, when he was no more than twelve or fifteen, he went west. Eventually he arrived in St. Paul, where, by the eighties, he was running a small wicker furniture business. In one of the panics of the nineties this business failed and he went to work as a salesman for Procter and Gamble. He was a small, quiet, ineffectual man with beautiful Southern manners, “very much the gentleman,” as his contemporaries said, “but not much get up and go.” He was, in any event, no match for his wife who, according to the gossip of the times, had persuaded him to propose to her by threatening to throw herself into the Mississippi, along which they were taking a walk. “Molly,” he used to say of Mrs. Fitzgerald, who was not very attractive, “just missed being beautiful.”

Mary McQuillan was the oldest of the four children of Philip McQuillan, an Irish immigrant who, after a start in Galena, Illinois, where he married his employer’s daughter, came on to St. Paul. Here, as a wholesale grocer, he eventually “reared a personal fortune estimated at from three to four hundred thousand dollars,” as the St. Paul papers put it, before he died at the age of forty-four of Bright’s disease. Fitzgerald’s Grandmother McQuillan’s imposing Victorian mansion then stood on Summit Avenue near Dale Street. It represented the solidity and permanence of wealth to a boy whose childhood was spent moving from apartment to apartment and hotel to hotel at the rate of better than one move a year, largely because of his father’s economic insufficiency. But the McQuillans did not represent breeding, for in addition to being “straight 1850 potato famine Irish” (as Fitzgerald once put it) they were eccentric, and their eldest daughter added to this eccentricity a directness which was also marked in her only son. “Whatever came into her head,” as one of her in-laws remarked, “came right out of her mouth.” She dressed carelessly and had her hair flying about her head in disorder. She was capable of appearing on a formal occasion wearing one old black shoe and one new brown one, on the principle that it is a good idea to break in new shoes one at a time (she had foot trouble and had to have her shoes made to order). She was an omnivorous reader of bad books and when Fitzgerald did a little piece about her at the time of her death, he made Alice and Phoebe Cary her favorite poets. Fitzgerald’s contemporaries remember her from their childhood as a witchlike old lady who carried an umbrella, rain or shine, and seemed always to be walking back and forth to the lending library with an armful of books. «She was devoted to her only son and spoiled him in a way which could only be partly counteracted by his maiden Aunt Annabel McQuillan. Near the end of his life he said: “I was fond of Aunt Annabel and Aunt Elise [Delihant, his father’s sister], who gave me almost my first tastes of discipline, in a peculiar way in which I wasn’t fond of my mother who spoiled me.”

His mother’s treatment was bad for a precocious and imaginative boy, and as Fitzgerald confessed to his daughter after she had grown up, “I didn’t know till 15 that there was anyone in the world except me….” He was thirty before experience succeeded in convincing him that “life was [not] something you dominated if you were any good.” “Even if you mean your own life,” as a friend wrote him when she read this remark in Fitzgerald’s autobiographical essay, “The Crack-Up,” “it is arrogant enough,—but life!” But it was something more complicated than arrogance. About Fitzgerald’s writing there was always an element of play, of imitative representation, as when he wrote a relative with whom he quarreled, “I will try to resist the temptation to pass you down to posterity for what you are” (and did not succeed; he put her in a story shortly afterwards), or when he remarked to his daughter of a passage in The Way of All Flesh, “My God—what precision of hatred is in those lines.I’d like to be able to destroy my few detestations… with such marksmanship as that.” Perhaps some conviction of “The Omnipotence of Thought” exists in all writing. In Fitzgerald’s case it carried over, like so much else, into his life, so that about everything he did for a long time there was an element of play, of an extravagance and simplicity of expectation which can only be described as childlike. It was this side of his nature which made him a lifelong practical joker and capable of enjoying success and pleasure as few people can.

As a small boy Fitzgerald lived, as he said later, “with a great dream” and his object was always to try to realize that dream. When he was four or five, for instance, he described his pony to his Grandmother McQuillan in minute detail; she was horrified that so small a child should have a pony, and it was not easy, after Scott’s persuasive description, to convince her that the pony was quite imaginary. With his gift for imagining games and his energy in executing them, he sought to be the leader wherever he went. As a child he had a hard time understanding that other children did not exist simply as material for his uses, and when they asserted their own egos with the brutal directness of children, he was always unprepared for it and deeply wounded. One of the bitterest memories of his childhood was his sixth birthday party, in Buffalo. To the vision of himself in his long-trousered sailor suit playing the suave and gracious host his imagination had given itself for days; he was now to enter at last into the world of society. He was out early to meet his guests. Nobody came. All afternoon he waited with his freshly pressed suit, his clean hands, his carefully brushed hair; but nobody ever came, and at last he went “sorrowfully in and thoughtfully consumed one complete birthday cake, including several candles (for I was a great tallow eater until I was well over fourteen).”

It is a consequence of this habit of projecting his wishes that he retained all his life the important emotional commitments of his growing up. It is partly because, as Americans, we all have similar commitments and because it never occurred to Fitzgerald, as it does to us, that he ought to pretend to have outgrown these commitments, that his work has such remarkable immediacy for us. He never buried his past because he was too naïve to realize that you are supposed to believe it is dead. It is not easy to convey the extraordinary energy with which his imagination responded and reached out to experience; he got something of what he felt into an incident—only the names are not actual—he used in The Romantic Egotist.

…one night… with Nancy Collum … I sat in a swaying motor-boat by the club-house pier [at White Bear], and while the moon beat out golden scales on the water, heard young Byron Kirby propose to Mary Cooper in the motor-boat ahead. It was entirely accidental, but after it had commenced, wild horses could not have dragged Nancy and me from the scene. We sat there fascinated. Kirby was an ex-Princeton athlete and Mary Cooper was the popular debutante of the year. Kirby had a fine sense of form and when at the end of his manly pleading she threw her arms about his neck and hid her face in his coat, Nancy and I unconsciously clung together in delight…. when finally, unable to keep the secret, I told Kirby about it, he bought me three packages of cigarettes, and slapped me on the back telling me to be a sport and keep it very dark. My enthusiasm knew no bounds, and I was all for becoming engaged to almost anyone immediately.

Given Fitzgerald’s capacity for hero-worship, for identifying himself with some person he admired and then imagining himself as that person, he was bound to make an heroic image for himself of the athlete, and the process by which he did so can be traced step by step. It began when he was very young, at a small Y.M.C.A. basketball game. “The Captain of the losing side was a dark, slender youth of perhaps fourteen, who played with a fierce but facile abandon that… sent him everywhere around the floor pushing, dribbling, andshooting impossible baskets from all angles…. Oh, he was fine, really one of the finest things I ever saw…. after I saw him all athletes were dark and devilish and despairing and enthusiastic….” Here was a concrete instance of the romantic heroism vaguely outlined by Fitzgerald’s imagination, and the image and the idea were fused by this experience. With his habit of struggling stubbornly to achieve in his own life the ideals he imagined, he went out himself for basketball and, trying to play with the “fierce but facile abandon” of his ideal, got a reputation for being a ball hog.

This vision of the heroic athlete was rapidly given an elaborate context by the boys’ books he read and acquired a heavy burden of conventional detail. The hero was a prep-school or college boy, a male Cinderella, small and discriminated against, who by some dramatic and unlikely display of pluck won the big game for St. Regis or Princeton. This dream was only gradually modified and never wholly uprooted by the hard realities of prep-school and college life. It put him on the Newman football team despite his dislike of the game and sent him out for Freshman football at Princeton—at one hundred and thirty-eight pounds. Every so often the ideal would achieve a new personification: Sam White in the Princeton-Harvard game of 1911; Hobey Baker, the Princeton captain of 1913, “slim and defiant”; “the romantic Buzz Law whom I had last seen one cold fall twilight in 1915, kicking from behind his goal line with a bloody bandage round his head,” the mere sight of whom, “a slender, dark-haired young man with an indolent characteristic walk,” could make “something stop inside” Fitzgerald when they passed on the Champs Elysées ten years after they had left college.(The reference to Sam White is in F. Scott Fitzgerald 's Scrapbook, the reference to Hobey Baker in THIS SIDE OF PARADISE, NEW YORK, 1920, p. 46. The meeting with Buzz Law is described in 'Princeton,' College Humor, December, 1927, p. 28. Possibly Fitzgerald's memory played him slightly false here. There is a photograph of Law kicking from behind his own goal line with a bandage round his head in the Yale-Princeton game of 1913. But those were brave days when many backs played without helmets; Law was one of them and probably there were games in 1915 too in which he kicked from behind goal lines wearing a bloody bandage. The statement about seeing Law in Paris should be compared to Fitzgerald's remark on the same occasion in a letter to Ludlow Fowler: 'Buzz Law, an old hero of mine, passed me on the street the other day looking by no means distinguished.' (November 6, 1926.) In these figures he found, as he put it once about Hobey Baker, “an ideal worthy of everything in my enthusiastic admiration, yet consummated and expressed in a human being who stood within ten feet of me.”

This is a characteristic instance of the process by which Fitzgerald’s imagination took hold of—or was taken hold ofby—the concrete particulars of American experience and gradually made out of them symbols for the whole of human experience. There may not be potential in Buzz Law much of the full moral value of the tragic hero, but he does have the advantage of being, as hero, genuine and indigenous; such as it was, his kind of heroism is something every American knows at first hand, and something that Fitzgerald responded to with his whole nature.

All his life he retained this kind of imaginative innocence. The most vivid image of aristocratic pride and self-possession he had ever seen was his boyhood rival, Reuben Warner, sitting with “aloof exhaustion” at the wheel of his Stutz Bearcat “with that sort of half-sneer on [his] face which I had noted was peculiar to drivers of racing cars.” Fitzgerald could joke about how he had slouched “passionately” at the wheel of the family car in an effort to realize this image himself. But the image nonetheless remained to haunt him all his life, as did all the deeply felt experiences of his youth. “It was on the cards,” he would say to his daughter, “that Ginevra King should get fired from Westover—also that your mother should wear out young.” In any objective sense, the coupling of Zelda’s tragedy and Ginevra King’s departure from Westover is ludicrous. But their essential meaning was the same, and Fitzgerald, having felt both deeply, tended to ignore the discrepancy in objective importance.

If it was natural enough for Fitzgerald to apply to the normal boy’s dream of social achievement and athletic success his habit of energetic idealization, it was also natural that others should resent his efforts to use them as bit players in his drama. But this resentment was something that his home environment had not in the least prepared him for. On the contrary, his mother’s undiscriminating admiration had quite the opposite effect.

This situation was the source of two important characteristics of the adult Fitzgerald. Here, in the first place, was the beginning of that deep-seated social self-consciousness which is marked in his adult years. The ambition to lead, to succeed, to fulfill his dream of being a first-rate man had necessarily to be realized in the world he lived in. Whatever his scorn of that world—and it was considerable—he could not ignore it. At the same time the very intensity of his idealization of it and of his efforts to succeed puzzled and alienated his contemporaries who, the moment he ceased to charm them, turned on him. Not understanding, even as an adult, these sudden changes, he became uncertain of his social standing early in life. This uncertainty shows up clearly in his school days.

This situation must also have been the source of his unusual feelings about his mother. Even as a young boy he alternated between being ashamed of her eccentricity and being devoted to her. When he got away to school and realized how bitterly he had to suffer because of the way she had spoiled him, he was very angry at her. Yet when she died in 1936, at a time when his morale was at its lowest point and he was in serious financial straits, he remarked that “she was a defiant old woman, defiant in her love for me in spite of my neglect of her and it would have been quite within her character to have died that I might live.” After he finished The Great Gatsby he started to write a novel about matricide called The Boy Who Killed His Mother, on which he worked for four years without making much headway. While he was at work on it his mother came to Paris to visit him, and he anticipated her arrival by going around Paris telling all his friends what a dreadful old woman she was (though his friends, to their surprise, found her perfectly all right when she finally appeared). This attack on her may have been partly a product of his social uncertainty; but it was partly a product of his personal feelings about her. At about this time he also wrote a comic ballad about a dope fiend of sixteen who murdered his mother.

In a dear little vine covered cottage

On Forty-second Street

A butcher once did live who dealt

In steak and other meat.

His son was very nervous

And his mother him did vex

And she jailed to make allowance

For his matricide complex

And now in old Sing Sing

You can hear that poor lad sing.

Just a boy that killed his mother

I was always up to tricks

When she taunted me I shot her

Through her chronic appendix

I was always very nervous

And it really isn’t fair

I bumped off my mother but never no other

Will you let me die in the chair?…

It was dope that made me do it

Otherwise I wouldn’t dare

’Twas ten grains of morphine that made me an orphine

Will you let me die in the chair?

With his considerable amateur talent for acting, Fitzgerald used to deliver this ballad at parties, his face powdered white, a cigarette dangling from his mouth, and his hands trembling.

In the spring of 1898, when he was two years old, the Fitzgeralds were moved to Buffalo by Procter and Gamble. Except for two and a half years from 1901 to 1903 when they lived in Syracuse, they remained in Buffalo until 1908. In March of that year Mr. Fitzgerald was fired. The experience was a terrifying one for his young son who, when the news came, prayed silently that they might not have to go to the poorhouse. In July they moved back to St. Paul. Mrs. Fitzgerald took her son on frequent trips during thisperiod, to Orchard Park, Atlantic City, the Catskills and Adirondacks, and Chautauqua. They feared, not without reason, that he was consumptive. He was also taken to visit Randolph, his Aunt Eliza Delihant’s place in Montgomery County, Maryland, and there, in April, 1903, he was a ribbon holder at the wedding of his cousin Cecilia, with whom he later fell in love when she was a young widow living in Norfolk and he was an undergraduate; she turns up in This Side of Paradise as Clara.

When he was four his parents tried to send him to school but he cried so hard they took him out after one day, and when he was sent to the Holy Angel’s Convent in Buffalo at the age of seven it was with the understanding that he need go only half a day—either half he chose. He had a childhood horror of dead cats and remembered all his life a vacant lot in Syracuse that was full of them. He also developed a curious shame of his own feet and refused to go barefoot or even to swim because it involved exposing them. His father encouraged in him an interest in American history so that he remembered from his sixth year books about the Revolution and the Civil War, and, after seeing a play on the subject, spent hours in the attic dressed in a red sash which, he was convinced, made him look like Paul Revere. As he grew older, however, he turned the attic into a gymnasium and persuaded his family to give him a football outfit, complete with shinguards.

In school he was always in trouble with his teachers. An episode in one of the unpublished Basil stories which is a recollection of his own experience at Miss Nardon’s Academy shows why.

“So the capitol of America is Washington,” said Miss Cole, “and the capitol of Canada is Ottawa—and the capitol of Central America—“

“—is Mexico City,” someone guessed.

“Hasn’t any,” said Basil absently.

“Oh, it must have a capitol,” said Miss Cole looking at her map.

“Well, it doesn’t happen to have one.”

“That’ll do, Basil. Put down Mexico City for the capitol of Central America. Now that leaves South America.”

Basil sighed.

“There’s no use teaching us wrong,” he suggested.

Ten minutes later, somewhat frightened, he reported to the principal’s office where all the forces of injustice were confusingly arrayed against him.

The forces of injustice continued to array themselves against him in this way for the rest of his academic career at St. Paul Academy and Newman and Princeton.

Though the influence of his mother and his energetically pious Aunt Annabel was probably as great as the influence of his father, Fitzgerald’s early memories are all of what he learned from his father. The code of the Southern gentleman which his father taught him at this time—the belief in good manners and right instincts—stayed with him as an ideal all his life. Nick Carraway, the narrator in The Great Gatsby who is from St. Paul, Minnesota, has been told by his father to remember, when he is tempted to criticize others, that “a sense of the fundamental decencies is parcelled out unequally at birth”; in Tender Is the Night Dick Diver’s father, a clergyman from Buffalo, New York, has taught him the need for “‘good instincts,’ honor, courtesy, and courage,” those “eternal necessary human values” which, as Fitzgerald said in “Echoes of the Jazz Age,” were inadequately provided by the hedonistic twenties. All these were the direct product of his own father’s example.

I loved my father—he wrote later—always deep in my subconscious I have referred judgments back to him, what he would have thought, or done. He loved me—and felt adeep responsibility for me—I was born several months after the sudden death of my two elder sisters & he felt what the effect of this would be on my mother, that he would have to be my only moral guide…. What he told me were simple things.

“Once when I went in a room as a young man I was confused so I went up to the oldest woman there and introduced myself and afterwards the people of that town always thought I had good manners.” He did that from a good heart that came from another America—he was much too sure of what he was … to doubt for a moment that his own instincts were good. …

We walked down town in Buffalo on Sunday mornings and my white ducks were stiff with starch & he was very proud walking with his handsome little boy. We had our shoes shined and he lit his cigar and we bought the Sunday paper. When I was a little older I did not understand at all why men that I knew were vulgar and not gentlemen made him stand up or give the better chair on our verandah. But I know now. There was new young peasant stock coming up every ten years & he was one of the generation of the colonies and the revolution.

He tried to tell his son stories which would embody the feelings he inherited from his past, but his son did not think them very good stories at the time; “[my father] came from tired old stock, with very little left of vitality and mental energy,” he wrote in The Romantic Egotist. Later he understood better; “his own life,” he wrote Harold Ober in 1926, “after a rather brilliant start back in the seventies has been a ‘failure’—he’s lived always in mother’s shadow and he takes an immense vicarious pleasure in any success of mine.” (One of the stories Fitzgerald remembered was about how his father had as a small boy helped one of Moseby's guerrillas to escape. He tells this story in 'The Death of My Father' and in Doctor Diver's Holiday, pp. 455-456. (Both of these are still in ms.) A much abbreviated version of the scene in Doctor Diver's Holiday appears in TENDER IS THE NIGHT, chapter XVIII. Fitzgerald also wrote an inferior story called 'The End of Hate' based on this story of his father's; it appeared in Collier's, June 22, 1940).

By the time the Fitzgeralds moved back to St. Paul in July, 1908, when Scott was twelve, he had got well started on most boyhood interests. He had fallen in love with a girl at Mr. Van Arnem’s dancing school, had organized a play in a neighbor’s attic, had collected stamps and cigar bands, played football on a neighborhood team (“guard or tackle and usually scared silly”), written a detective story and the beginning of a history of the United States (it never got past the battle of Bunker Hill), sung for visitors (at his mother’s insistence) “Way Down in Colon Town” and “Don’t Get Married Any More,” told his first lie at confession “by saying in a shocked voice to the priest ‘Oh, no, I never tell a lie’”—exactly as does the little boy in “Absolution.” He was like Basil Duke Lee at the same age, “by occupation actor, athlete, scholar, philatelist and collector of cigar bands.”

2

The Fitzgeralds’ return to St. Paul opened a new world to their son. Up to that time his family had moved regularly every September, so that he had hardly lived in a single neighborhood long enough to become a part of it. But for the next ten years of his life he was to be one of the group of children who lived in the neighborhood of Summit Avenue. As usual the Fitzgeralds moved each year—from 294 Laurel Avenue to 514 Holly Avenue; then to 509 and 499 Holly. Here they stayed for three years before they moved again into 593 Summit Avenue, one of a row of brownstone-front houses near Dale Street. Summit Avenue is St. Paul’s show street, “a museum,” as Fitzgerald later called it, “of American architectural failures.” Dale Street, however, is just about where Summit Avenue lapses into a quite ordinary street, a decline which is signaled by the row of narrow-fronted, attached houses in one or the other of which—they moved from 593 to 599 in 1918—the Fitzgeralds lived the rest of their lives in St. Paul. None of these moves within St. Paul, however, took them out of the Summit Avenue community. Thus, as Fitzgerald grew up, his family moved gradually around the periphery of St. Paul’s finest residential district,settling finally at the end of its best street. The symbolism is almost too neat, and Fitzgerald was acutely aware of it. When This Side of Paradise was accepted in 1919, for instance, he sat down at once to write his childhood friend, Alida Bigelow, about his success. The letter is headed:

(599 Summit Avenue)

In a house below the average

Of a street above the average

In a room below the roof.

I shall write Alida Bigelow….

For if St. Paul had then a great deal of the simple and quite unself-conscious democracy of the old middle-western cities, it also had its wealth and its inherited New England sense of order. The best people in St. Paul are admirable and attractive people; but they are, in their quiet way, clearly the best people. They do not forget the Maine or Connecticut “connection”; they send their children to Hotchkiss or Hill or Westover, to Yale or Princeton, to be educated; they are, without ostentation or affectation, cosmopolitan.

At the top—Fitzgerald once wrote of St. Paul—came those whose grandparents had brought something with them from the East, a vestige of money and culture; then came the families of the big self-made merchants, the “old settlers” of the sixties and the seventies, American-English-Scotch, or German or Irish, looking down somewhat in the order named—upon the Irish less from religious difference—French Catholics were considered rather distinguished—than from their taint of political corruption in the East. After this came certain well-to-do “new people”—mysterious, out of a cloudy past, possibly unsound.

This was the world Fitzgerald grew up in, desiring with all the intensity of his nature to succeed according to its standards and always conscious of hovering socially on the edge of it, alternating between assertion and uncertainty because of his acute awareness that his foothold was unsure. None of the things that bothered him would have made a serious impression on him had it not been for his already established insecurity. Fitzgerald’s younger sister, Annabel, for instance, appears to have settled happily and without self-consciousness into the social life of the community. She was a pretty girl, very quiet and self-possessed. Fitzgerald’s imagination seems to have fixed itself for a time on her and to have sought through her, as it was so often in later life to seek its satisfactions through the lives of others, the “interior security” and exterior success which he felt he never quite achieved in his own person. He believed that only her quietness prevented her achieving the romantic social success in which he took such innocent delight. To remedy this deficiency he provided her with a fashionable “line” with which she would amaze her dance partners. Annabel eventually married a young naval officer, Clifton Sprague, who was later to distinguish himself as the commander of the tin-can fleet which fought gallantly at the battle of Leyte Gulf in 1944.

It would be an exaggeration to suggest that Fitzgerald was not often happily at ease socially too. Still, when he came to use his childhood memory of White Bear in the summer of 1911 for “Winter Dreams,” he made the hero a caddy. Gradually, as he grew older, he became more and more self-conscious about the small social gestures which ought to become more and more habitual. The end of this development was his lifelong habit of attacking the task of conducting himself like a gentleman with nervous anxiety. The habit was all the more remarkable because he had great personal charm when he chose to exert it, and because a part of his mind understood the situation perfectly, knew that one does not become a gentleman by acting the part consciously, understood that alienation is self-induced.

A great many things in his boyhood situation had pitfalls for him. He was embarrassed by his mother; and he was troubled by his father’s trade. His father was now a wholesale grocery salesman, a job he probably obtained through the old McQuillan connection. It was said in St. Paul that he made just about enough to pay for the desk in his brother-in-law’s real estate office from which he conducted his business. Mr. Fitzgerald was even required to charge his postage stamps at the corner drugstore. Such things were a constant humiliation to his son, who loved him and never forgot his mother’s “Well, if it wasn’t for [Grandfather McQuillan] where would we be now?”

I am—Fitzgerald wrote long afterward—half black Irish and half old American stock with the usual exaggerated ancestral pretensions. The black Irish half of the family had the money and looked down upon the Maryland side of the family who had, and really had, that… series of reticences and obligations that go under the poor old shattered word “breeding”. … So being born in that atmosphere of crack, wise crack and countercrack I developed a two cylinder inferiority complex. So if I were elected King of Scotland tomorrow after graduating from Eton, Magdelene the Guards, with an embryonic history which tied me to the Plantagonets, I would still be a parvenue. I spent my youth in alternately crawling in front of the kitchen maids and insulting the great.

Thus, very conscious of a dubious gentility and an inadequate family income, he set out to make his way in St. Paul and at St. Paul Academy. He was a small, handsome, blue-eyed boy, full of energy and invention and already so determined to make a success that the school magazine, Now and Then, quickly tagged him as the man who knew exactly “How to Run the School,” and asked rather quarrelsomely if there were not someone who would “poison Scotty or find somemeans to shut his mouth.” “He wasn’t popular with his schoolmates,” said his headmaster. “He saw through them too much and wrote about it.”

On the long, wonderful summer visits at White Bear Lake with his friends Cecil Read and Robert Clark—whose families could afford places at White Bear—he was constantly being beaten at games, even by girls. Nonetheless, as he was to do all his life, he stuck grimly to it. He played football, first with a corner-lot team which he and his friends organized (and got a broken rib), and then on intramural teams. Once in the fall of 1909 he got into an Academy game; “The Academy outweighed the ’summits’ about sixty pounds,” says Now and Then. “On account of this the Academy put some of their lightest men on the line.” He was on the third-string “Blue” basketball team and was the second-string pitcher for the Academy’s third team, which had a disastrous season that year.

But if his athletic career was an unbroken series of unadmitted defeats, he had some success in an extracurricular way and as a literary man. He was the leader and idea man for a club, known first as the Scandal Detectives and later as the Gooserah, which had its headquarters in the loft of his friend Cecil Read’s barn on Holly Avenue and later in the attic of the Reads’ new house on Summit. Here, when Fitzgerald was reading The Three Musketeers, they were taught by him to fence and, when he read Arsène Lupin, to be detectives: everything he read had to be lived. Under the stimulus of romances about the Ku Klux Klan, the Gooserah also organized “adventures.” One of these was an attack on another boy of their own age, Reuben Warner, who had captured the affections of the girl Fitzgerald admired. Their skillfully conceived piece of terrorization, which ended with Mr. Warner’s calling out the police, was used by Fitzgerald in his story “The Scandal Detectives” in Taps at Reveille?

It was widely known in these circles, too, that Scott kept,locked in a box under his bed, a manuscript known as his “Thoughtbook,” which was believed to contain candid and destructive accounts of all his contemporaries. This document still exists, fourteen pages torn from a notebook and covered with Fitzgerald’s boyish scrawl. It was the source for the “Book of Scandal” Basil kept, though its main preoccupation is neither scandal nor his friends but girls. As the work of a fourteen-year-old boy it is remarkable for the minuteness of its analyses of people and of Fitzgerald’s feelings about them; its interest in the small shifts of power within his social group is unflagging. “[Paul Ballion],” he will write, “was awfully funny, strong as an ox, cool in the face of danger polite and at times very interesting. Now I dont dislike him. I have simply out grown him.” Or: “Since dancing school opened this last time I have deserted Alida [Bigelow]. I have two new Crushes. To wit—Margaret Armstrong and Marie Hersey…. The 2nd is the prettiest the 1st the best talker. The 2nd the most popular with T. Ames, L. Porterfield, B. Griggs, C. Read, R. Warner ect. and I am crazy about her. I think it is charming to hear her say, ‘Give it to me as a comp-pliment’ when I tell her I have a trade last for her. I think Una Baches is the most unpopular girl in dancing schools. Last year in dancing school I got 11 valentines and this year 15.” The battle, as this passage shows, was for general popularity. It was the age of character books and the lock of hair and Fitzgerald showed great curiosity as to how many girls listed him as their “favorite boy” or the one they would “like to kiss most.” He was also a tireless collector of locks of hair, which he would mount on pins and wear on his coat lapel. His success was considerable, for he was an attractive boy.

As they grew older, the crowd began to gather regularly in the yard of the Ames house on Grand Avenue which Fitzgerald later described with such fidelity in “The Scandal Detectives.” It was here that he had, as he put it in his Ledger, his first “faint sex attraction.”

Basil—he wrote of the character to whom he ascribed this experience—rode over to Imogene Bissel and balanced idly on his wheel before her. Something in his face then must have attracted her, for she looked up at him, looked at him really, and slowly smiled…. For the first time in his life he realized a girl completely as something opposite and complementary to him, and he was subject to a warm chill of mingled pleasure and pain. It was a definite experience and he was immediately conscious of it…

“Can you come out tonight?” he asked eagerly. “There’ll probably be a bunch in the Whartons’ yard.”

“I’ll ask mother.” …

“Listen,” he said quickly, “what boys do you like better than me?”

“Nobody. I like you and Hubert Blair best.”

Basil felt no jealousy at the coupling of this name with his. There was nothing to do about Hubert Blair but accept him philosophically….

“I like you better than anybody,” he said deliriously.

The weight of the pink dappled sky above him was not endurable. He was plunging along through air of ineffable loveliness….

Meanwhile he had begun to write and had become St. Paul Academy’s star debater (no one had found a means to shut him up). Having had to read Sir Walter Scott in school, he turned out a complicated story of knights and ladies called “Elavo”; and having become an expert on the detective story on his own initiative, he wrote “The Mystery of the Raymond Mortgage.” This story was printed in Now and Then in September, 1909; it was his first published work. It is, for a schoolboy, a skillfully plotted little murder story and, in its sedulous imitation of the style of such works, often unconsciously very funny. “The morning after I first saw John Syrel, I proceeded to the scene of the crime to which he had alluded”; “‘What have you heard?’ I asked. ‘I have an agent in Indianous,’ he replied, ‘in the shape of an Arab boy whomI employ for ten cents a day’”; this is the quintessence of the Doyle style. “… through some oversight,” as Fitzgerald himself remarked later, “I neglected to bring the [mortgage] into the story in any form”; but no one seemed to notice. This success was followed by two romantic Civil War stories, “A Debt of Honor” and “The Room with the Green Blinds,” and a football story called “Reade, Substitute Right Half.”

He also became a playwright. He had always loved plays, from the time he had enacted Paul Revere in his red sash in the attic in Buffalo, and he never tired of reading the parts for his friend Tubby Washington’s toy theater while Tubby was reduced to moving the cardboard figures around the stage. When he was reading Arsène Lupin, he wrote and managed to produce a half-hour detective play in the Ames’ living room; its cast—Slim Jim, Anne the girl, Mike a policeman—foreshadows the more ambitious “Captured Shadow” written two years later. The great moment came, however, when Miss Elizabeth Magoffin, a St. Paul lady of romantic tendencies with an interest in the theater, organized a modest children’s performance of a comedy called “A Regular Fix.” It was produced at the Academy in August, 1911. She had hardly reckoned on the effect of this experience on Fitzgerald, who sat down at once and wrote a melodramatic western called “The Girl from Lazy J,” of which he was both star and director. The ever-faithful Tubby drove director Fitzgerald to despair with his repeated failure, as the vengeful Mexican bandit, to pause at the break in his key line, “Now I will have revenge—but wait.”

These multifarious extracurricular activities had seriously affected Fitzgerald’s school work. He was incapable of learning anything which did not appeal to his imagination and always depended on his wealth of scattered information about American history and certain areas of literature to distract attention from his failure to have prepared the day’s assignment. But since he had become a writer he had taken toscribbling on the blank pages of his textbooks throughout all his classes, and it became apparent that drastic measures would have to be taken. A family conference was held and it emerged that Aunt Annabel was prepared to foot the bill for a boarding school, provided it was a good Catholic school. Plans were therefore laid to send Fitzgerald to Newman in the fall of 1911. (Mr. Turnbull says, 'Fitzgerald's sister told me that Aunt Annabel McQuillan sent her to Rosemary Hall but did not pay Fitzgerald's way at Newman, as was previously thought' (Scott Fitzgerald, p. 338). It was Miss Annabel McQuillan herself who told me she sent Fitzgerald to Newman, but she was a very old lady when I talked to her and may have been confused).

He faced this prospect with his usual burst of imaginative fervor. All his knowledge of boarding school life, as he had learned about it from Ralph Henry Barbour and others, was summoned to the task of providing an adequate dream of social and athletic success in this glittering eastern world. At the same time some need of his imagination for thinking of himself now as a man asserted itself. He had acquired his first adult long trousers and he began to make those characteristic American middle-class boys’ experiments with sex which are always conducted with working-class or lower middle-class girls—“chickens” they were then called. This was the summer he picked up a “chicken” at the State Fair with the result described in “Basil at the Fair.” (The episode is also described in The Romantic Egotist, chapter I, p. 32). During this summer he and Tubby took to picking up such girls regularly; they would get, as they supposed, very drunk on a bottle of drugstore sherry and make tentative sexual ventures.

3

Fitzgerald’s two years at Newman were a repetition on a larger scale of his experience at St. Paul Academy. He set off for Newman full of dreams of success and popularity and yet acutely aware of his divided nature. He once recalled in detail his judgment of himself at this time.

… Physically—I marked myself handsome; of great athletic possibilities, and an extremely good dancer…. Socially … I was convinced that I had personality, charm,magnetism, poise, and the ability to dominate others. Also I was sure that I exercised a subtle fascination over women. Mentally … I was vain of having so much of being talented, ingenious and quick to learn. To balance this, I had several things on the other side: Morally—I thought I was rather worse than most boys, due to a latent unscrupulous-ness and the desire to influence people in some way, even for evil… lacked a sense of honor, and was mordantly selfish. Psychologically … I was by no means the “Captain of my fate.” … I was liable to be swept off my poise into a timid stupidity. I knew I was “fresh” and not popular with older boys…. Generally—I knew that at bottom I lacked the essentials. At the last crisis, I knew I had no real courage, perseverance or self respect.

This is a remarkably honest account of himself; it shows, as he observed later in The Romantic Egotist, that “all my inordinate vanity… was on the surface… and underneath it, came my own sense of lack of courage and stability.”

He was, in short, the Basil of “The Freshest Boy.” “Basil… had lived with such intensity on so many stories of boarding-school life that, far from being homesick, he had a glad feeling of recognition and familiarity.” “With what he considers kindly intent” he makes to the older boy he is traveling to school with “the sort of remark that creates lifelong enmities”:

“You’d probably be a lot more popular in school if you played football,” he suggested patronizingly.

Lewis did not consider himself unpopular. He did not think of it in that way at all. He was astounded.

“You wait!” he cried furiously. “They’ll take all that freshness out of you.”

“Clam yourself,” said Basil, coolly plucking at the creases of his first long trousers. “Just clam yourself.”

“I guess everybody knows you were the freshest boy at the Country Day!”

“Clam yourself,” repeated Basil, but with less assurance. “Kindly clam yourself.”

“I guess I know what they had in the school paper about you—“

Basil’s own coolness was no longer perceptible…. [Lewis’s] reference had been to one of the most shameful passages in his companion’s life. In a periodical issued by the boys of Basil’s late school there had appeared, under the heading Personals:

If someone will please poison young Basil, or find some means to stop his mouth, the school at large and myself will be much obliged.

So too, Fitzgerald arrived at Newman, and, repeating his mistakes at St. Paul Academy, made himself the most unpopular boy in the school. “He saw now that in certain ways he had erred at the outset—he had boasted, he had been considered yellow at football, he had pointed out people’s mistakes to them, he had shown off his rather extraordinary fund of general information in class.” Football was a particularly sore point. “Newman was just a small school and football was practically a form of exercise in which everyone took part,” said one of his classmates years later; “but it was a key to prestige and that was the inducement [for Fitzgerald]. Fitz himself was ordinarily quite an indifferent player without real zest for the game and never went out for football at college, but by then there were other avenues for obtaining prestige for which he was better equipped.” His extreme good looks—even four years later he collected a painful number of votes as the prettiest member of his class at Princeton—helped to win him a quick reputation as a sissy. Within a month of his arrival he had had several fights forced on him, with the crowd always against him, and had been lectured on his freshness by a fellow student named Herbert Agar. His roommate remembered him years later as having had “the most impenetrable egotism I’ve ever seen”: he was constantly aware that “he was one of the poorest boys in a rich boys’ school.” He had the faculty as well as the students against him: he was never on time for classes or meals, and he could not be prevented from reading after lights; he was constantly on bounds. Ten years later he wrote of this time:

I was unhappy because I was cast into a situation where everybody thought I ought to behave just as they behaved—and I didn’t have the courage to shut up and go my own way, anyhow.

For example, there was a rather dull boy at school named Percy, whose approval, I felt, for some unfathomable reason, I must have. So, for the sake of this negligible cipher, I started out to let as much of my mind as I had under mild cultivation sink back into a state of heavy underbrush. I spent hours in a damp gymnasium fooling around with a muggy basket-ball….

And all this to please Percy. He thought it was the thing to do. If you didn’t go through the damp business every day you were “morbid.” … I didn’t want to be morbid. So I became muggy instead….

The worst of it is that this same business went on until I was twenty-two. That is, I’d be perfectly happy doing just what I wanted to do, when somebody would begin shaking his head and saying:

“Now see here, Fitzgerald, you mustn’t go on doing that. It’s—it’s morbid.”

But while a part of Fitzgerald did rebel from the start against the narrowness and tyranny of boarding-school life, a part of him was exactly like Percy. Some years later a shrewd observer who knew him at Officers’ Training School remarked of Fitzgerald that “he was eager to be liked by his companions and almost vain in seeking praise. At the same time he was unwilling to conform to the various patterns of dullness and majority opinion which would insure popularity.” At Newman, too, though he never gave up the pursuits which were supposed to lead to success, he could never quite do them in the conventional and accepted way.

During his first fall there he stuck grimly to his job on the scrub football team, struggled with stubborn courage to live down his unpopularity, and suffered deeply, as the “Incident of the Well-Meaning Professor” in This Side of Paradise shows. His greatest consolation was to escape from school to the theater in New York. His notes for this period are full of references to plays seen—The Little Millionaire, with George M. Cohan, Over the River, The Private Secretary, and above all, The Quaker Girl with Ina Claire and Little Boy Blue with Gertrude Bryant. He now added to his ambitions the intention to produce a great musical comedy and began to scribble librettos in his spare time. He went home for a brief, wonderful Christmas vacation and came back to find that his poor marks had put him back on bounds. But he settled down to try to make a new start. “It was a long hard time…. An indulgent mother had given him no habits of work and this was almost beyond the power of anything but life itself to remedy, but he made numberless new starts and failed and tried again.” Gradually his unpopularity waned and in the spring he won the Junior Field Meet, which gave him a tiny triumph to cling to. He went home for the summer chastened and improved.

During the summer he went through the characteristic cycle once more. “All one can know,” he once said of the age of fifteen, “is that somewhere between thirteen, boyhood’s majority, and seventeen, when one is a sort of a counterfeit young man, there is a time when youth fluctuates hourly between one world and another—pushed ceaselessly forward into unprecedented experiences and vainly trying to struggle back to the days when nothing had to be paid for.” In St. Paul his newly discovered consideration for others was, he found, a great social asset; for just a moment he was themost popular boy in the crowd. Then, realizing he was making a success, he began to talk about himself and quickly destroyed his popularity. He never forgot a dance at White Bear this summer which began with his having to beg a ride out with some boys who did not much want him—they were at the age when the possession of a car was immeasurably important—and ended with his being left out of a party which was organized right under his nose.

Happily, however, there was a diversion from this trouble. During the previous Christmas vacation he had seen a production of Alias Jimmy Valentine which had inspired him to write (on the train coming home for the summer) a similar drama called “The Captured Shadow.” This was to be the summer’s production of The Elizabethan Dramatic Club, a group of about forty young people organized for the purpose by Fitzgerald and directed by Miss Elizabeth Magoffin. Miss Magoffin was so carried away by the young author that she gave him her picture inscribed “To Scott ‘He had that spark—Magnetic mark—’ with the best love of the one who thinks so,” and added to her tribute an effusion entitled “The Spark,” which begins:

He was handsome—and straightness and firmness of form;

His lucid eyes shown with a light nigh divine;

His body enwrapping a soul big and warm,

A head and a heart—he was master of mind.

It was enough to try the modesty of any fifteen-year-old.

The play, which was performed at Mrs. Backus’ School on August twenty-third, was a great success. As Fitzgerald said in the story he wrote fifteen years later and called “The Captured Shadow,” “he had followed his models closely, and for all its grotesqueries, the result was actually interesting—it was a play”; it is. The action is carefully planned and there is plenty of plausible if conventional movement to theplot. It has its drunks, its comic gangsters, its elderly spinster, its Irish policeman and French detective. After originally casting himself for the second male lead, Fitzgerald was persuaded to play the suave gentleman burglar himself and “much favorable comment was elicited by the young author’s cleverness,” as the local press put it, from an audience of several hundred. The charity selected to provide a nominal cause for the production was the richer by sixty dollars. Thus Fitzgerald returned to Newman with a success behind him.

His second year at Newman was happier than his first. He made the football team, though not as a regular, and was even commended for his “fine running with the ball” in the Newman News’ account of the Kingsley game. But he was still without enthusiasm for the game and, on one occasion during the Newark Academy game, he avoided an open-field tackle so obviously that the quarterback, Donahoe, came over to him and said: “You do that again and I’ll beat you up myself.” With his wonderful Irish sense of the absurd and his ability to see it in his own experience, Fitzgerald loved to repeat this story about himself, and usually concluded his narration by remarking that he was so much more scared of Donahoe than of any ball carrier that he played a brilliant defensive game the rest of the afternoon. He made a good friend of Donahoe, and all his life admired with his characteristic generosity Donahoe’s possession of the persistence and self-control which he imagined—often quite wrongly—that he himself lacked. Respect for Donahoe’s modesty made him omit his name when he said in “Handle with Care” that he “represented my sense of the ‘good life,’ though I saw him once in a decade …. in difficult situations I … tried to think what he would have thought, how he would have acted.”

Meanwhile, still under the influence of The Quaker Girl and Little Boy Blue, he had gone on writing musical comedies. He read all the Gilbert and Sullivan he could get hold of andfilled his notebooks with ideas for songs and plots. Then sometime during the spring he picked up a musical score which he found on the top of a piano. It was for a show called “His Honor the Sultan” and, he discovered, had been produced by something called the Triangle Club of Princeton University. “That,” he wrote later, “was enough for me. From then on the university question was settled. I was bound for Princeton.” [But on another occasion he said it was seeing Sam White beat Harvard (in 1911, 8-6, by scoring a touchdown on a blocked kick) which decided him for Princeton. White’s touchdown was exactly the kind of sudden, brilliant, individual act which would have struck his imagination, especially as it occurred for him against a background of gallant defeats. “I think what started my Princeton sympathy,” he said on another occasion, “was that they always just lost the foot-ball championship. Yale always seemed to nose them out in the last quarter by superior ’stamina’ as the newspapers called it… I imagined the Princeton men as slender and keen and romantic, and the Yale men as brawny and brutal and powerful.” A decade later he was to make Tom Buchanan “one of the most powerful ends that ever played football at New Haven”; he is the contrasting type to “the romantic Buzz Law. “] It was not quite that easy; Aunt Annabel was still financing his schooling and did not want him to go to a Protestant college. She was, however, eventually talked around. Meanwhile Fitzgerald won the school Elocution Prize, played the part of Johann Ludwig, King of Schwartzbaum-Altminster, in a one-acter called “The Power of Music” which the Comedy Club produced, became an editor of the Newman News; won the Senior Field Day, pitched for the second team, and, in general, established himself as a respected if not brilliant member of the school community. In May he took his examinations for Princeton and “did a little judicious cribbing and never forgot it afterwards.” Even so he did not do well enough to assure his admission.

He went home for the summer to study for his September make-up examinations, to fall in love once more, and to work on another play for The Elizabethan Dramatic Club. This time he produced a Civil War melodrama called “The Coward” about a young Southerner who is “unwilling to don auniform and fight for the independence of the South.” “Playwright Fitzgerald… appear[ed] in the role of Lieut. Douglas,” a minor figure, but, though Miss Magoffin’s name still appears as the “Directress,” Mr. Scott Fitzgerald has crept in as Stage Manager, and the yellow posters for the performance announce that “Gustave B. Schurmeier presents LAURANCE BOARDMAN IN SCOTT FITZGERALD’S COMEDY ‘THE COWARD’…” The performance, on August 29, was a great success and this time the Baby Welfare League benefited by one hundred and fifty dollars from the first performance alone. There was a second at the White Bear Yacht Club a week later.

During this summer the youthful bottle of drugstore sherry began to give way to more adult drinks, and twice during the year Fitzgerald was drunk enough to remember the occasions as special ones. He began to be known around St. Paul as “a man who drank,” a reputation which gave him a certain romantic interest which he undoubtedly enjoyed. There was one sensational occasion when he scandalized St. Paul by disturbing the Christmas service at St. John’s, the most correct of Episcopal churches.

I entered quietly—Fitzgerald remembered afterwards—and walked up the aisle toward [the rector], searching the silent ranks of the faithful for some one whom I could call my friend. But no one hailed me. In all the church there was no sound but the metalic rasp of the buckles on my overshoes as I plodded toward the rector. At the very foot of the pulpit a kindly thought struck me—perhaps inspired by the faint odor of sanctity which exuded from the saintly man. I spoke.

“Don’t mind me,” I said, “go on with the sermon.”

Then, perhaps unsteadied a bit by my emotion, I passed down the other aisle, followed by a sort of amazed awe, and so out into the street.

The papers had the extra out before midnight.

Next chapter 2

Published as The Far Side Of Paradise: A Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald by Arthur Mizener (Rev. ed. - New York: Vintage Books, 1965; first edition - Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1951).