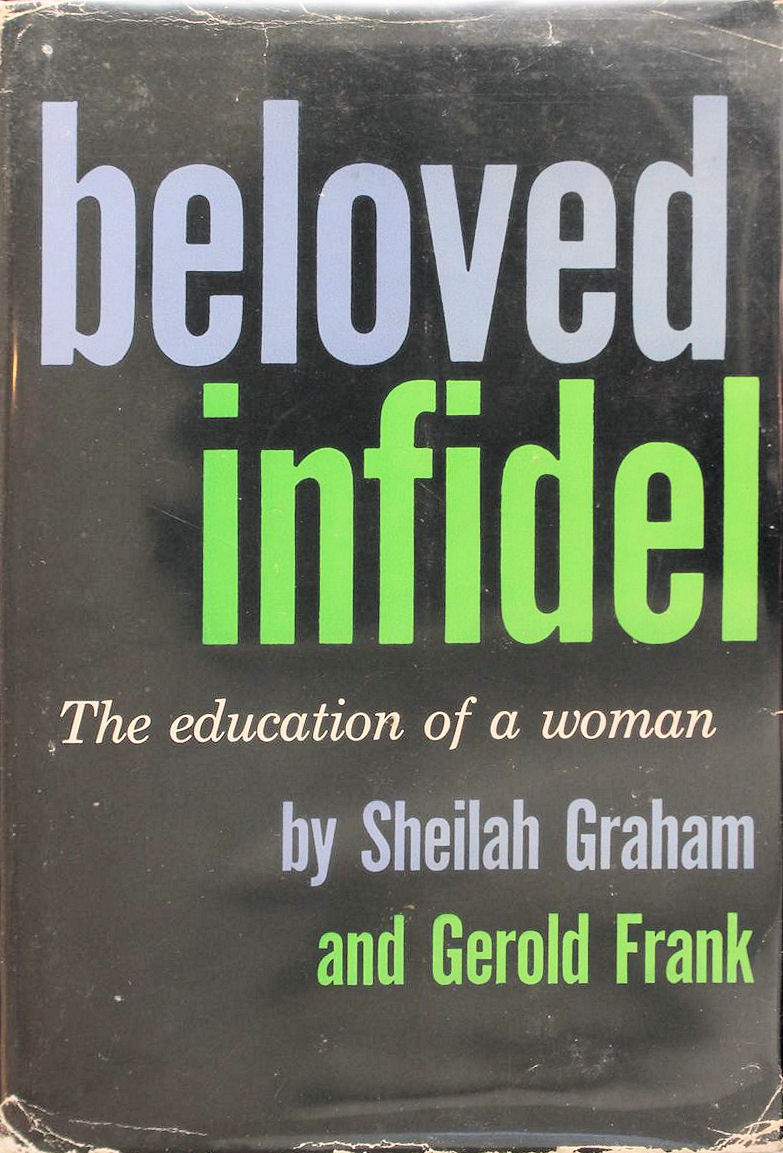

Beloved Infidel: The Education of a Woman

Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank

CHAPTER TWENTY

Scott, at Malibu. He is ii;i an ancient gray flannel bathrobe, torn at the elbows so that it shows the gray slipover sweater he wears underneath. He has the stub of a pencil over each ear, the stubs of half a dozen others— like so many cigars—peeping from the breast pocket of his robe. One side pocket bulges with two packs of cigarettes, from the other the top of his notebook can be seen. He has been working this week end on a script: his forelock sticks up, kewpie-doll fashion, and he paces back and forth, now and then pausing to kick away an imaginary pebble from in front of him.

In his room, off the captain’s walk, the floor is littered with sheets of yellow paper covered with a large flowing hand. He uses his stubby pencils—he sharpens them carefully with a penknife but never to a fine point because he bears down heavily—and writes at furious speed. As soon as one page is finished he shoves it off the desk to the floor and starts the next. Now he has come to a halt, hunting an elusive word. He may wait for twenty minutes, stubbornly, until it comes to him. He refuses to consult the dictionary or thesaurus. “No, it’s in my mind. I’ll think it out,” he says impatiently. “Anyway, if I go to the dictionary I get so fascinated I’m good for an hour there.”

I am learning more and more about Scott. He does not sleep well. At night I hear him pacing the floor, and in his medicine cabinet are sleeping pills and, to wake him in the morning, benzedrine. I shop and plan the meals but he eats less than he should, and often bizarre combinations that put Flora almost in tears: turtle soup and chocolate souffle can make a dinner for him. He lives through the day on Coca-Colas and highly sweetened black coffee, sometimes topped off with fudge, as though he cannot get enough sugar.

He follows world events avidly. I marvel how, for him, what happens today falls into place with what happened fifty years ago, a century ago. History lives for him. In contrast, to me it is as if it had never happened. How do we know there was a French Revolution? Or that Julius Caesar ever lived? Who cares? I can’t relate them to me, so why should they be so important? I know that Scott isn’t getting along well at Metro, that he worries about Zelda and Scottie and himself—yet he is concerned with everything about him. Is it that I am not noble enough to be genuinely interested in anything except my own needs? Or is it that I’m not well-enough educated to put together this jigsaw puzzle of past and present?

On Sunday mornings we sit before the Cases’ enormous console radio, listening to Hitler’s speeches. They infuriate Scott. He jumps up and pads restlessly about the room. “They’re going to do it again. They’re going to have another war—and we’ll be in it, too.” He sits down, lights a cigarette, listens again to the ranting, hysterical voice, the thunderous “Sig Heill Sig Heil! Sig Heil!” It echoes through our little beach house. He turns to me. “I’d like to fly over there and assassinate Hitler before he starts another war. I’d do it, too, by God!” He tells me, with a sudden, disarming smile, “You know, Sheilo, I wanted to fight in the last war. They pulled the rug from under me. The Armistice came and I never got across.”

We switch off the radio and Scott talks about the studio. He is working with collaborators, and unhappy. “They see it one way, I see it another. I’ve got to get them off the script,” he says. He cannot tolerate the endless story conferences. “All the brains come in,” he says. “They sit around a table. They talk about everything except the subject in hand—and when they do talk about that, they don’t know what they want, they don’t know where they’re going, they repeatedly change their minds —it’s disgraceful.” After six months of strenuous work he had completed the screenplay of Three Comrades, only to discover that Mankiewicz, his producer, had rewritten it. Infuriated, Scott dashed off a bitter, profane letter to him. I prevailed upon Scott to tone it down. “You’ll only antagonize him and he’ll never restore your script,” I said. Even in its restrained form, Scott’s letter reflected his intense hurt. “To say I’m disillusioned is putting it mildly, . . . You had something and you have arbitrarily and carelessly torn it to pieces. ... I am utterly miserable at seeing months of work and thought negated in one hasty week. Oh, Joe, can’t producers ever be wrong? I’m a good writer—honest I am. ...”

When Three Comrades opened, Scott and I drove into Hollywood to see it. “At least they’ve kept my beginning,” he said on the way. But as the picture unfolded, Scott slumped deeper and deeper in his seat. At the end he said, “They changed even that.” He took it badly. “That s.o.b.,” he growled when he came home, and furiously, helplessly, as though he had to lash out at something, he punched the wall, hard. “My God, doesn’t he know what he’s done?” Scott had now been on four pictures and his one screen credit—the all-important requirement for future work in Hollywood—was on a picture he was ashamed of.

There had been no drinking. Nor did he allow me to refer to the subject. From his nurse at the Garden of Allah I had learned the nature of his three-day cures. They were periods of intense bodUy torture in which he had to be fed intravenously, he retched day and night, tossed and turned sleeplessly, and emerged wan, shaken, bathed in sweat, utterly exhausted. I knew now why he had refused to let me see him at such times. But I had said once, at Malibu, “Now, don’t you think it was silly to have gone through all that agony for the stuff in a bottle?”

He had become angry, an anger of great reserve and great dignity. His face paled, his eyes seemed to grow closer together, his nose became long and thin with annoyance, his face dropped but with his head up he said sharply, almost arrogantly, flinging the words at me, “It’s none of your business. I don’t care to discuss it.” Then, abruptly, “About dinner—will you ask Flora to make me a lettuce salad and oyster broth?”

I came to know other aspects of Scott. I had counted on getting him bronzed and healthy in the sun and fresh air, but he avoided the sun. When we strolled on a Saturday afternoon to the Malibu Inn to spend an hour at the football slot machine, Scott insisted on walking on the shady side of the road. He never swam or even waded in the inviting surf, although 1 took a dip every day. “I’m too busy—I have work to do,” he would say. Then, one morning, by mistake I lifted his cup of coffee to my lips. He dashed it out of my hand. “Don’t ever use my cups or spoons or towels or anything else of mine,” he said sharply. “I have tuberculosis.” A surge of terror swept through me: my father had died of tuberculosis. “Scott, are you sure? How do you know?” He looked at me. “I’ve had it on and off since college. It’s not bad now but it flares up if I don’t watch myself.” That explained his raincoat and scarf in July, his avoidance of the sun and the water. I thought, perhaps he does have T.B. Or is this one of his pranks? Or is he a hypochondriac? I recalled that if I drove over twenty miles an hour he would gasp, “My God, slow down, you’re killing me.” Does he imagine things? At newsreels we moved two and three times during the evening because he insisted the people seated behind him were kicking the back of his chair. Each time we moved I wondered why this never happened to me.

Though Scott involved himself in everything I did, checking over my contracts and even my business letters, he remained curiously aloof toward my column. He was not interested in reading it. He accepted it as the way I earned my living but he gave it no further attention. Once however—as my champion—he helped me with it. This came after an upsetting encounter with Constance Bennett. One day I visited her set, picked up a few items and prepared to leave, just as happy that I hadn’t come upon Miss Bennett, about whom I had written rather un-flatteringly. At this moment her producer, Milton Bren, accosted me. “Have you met Connie Bennett yet?” “No,” I said, “but I must rush away.” “Oh, come on, she’s on the set, I’ll introduce you,” he said. He took me to a sound stage and there was Miss Bennett holding court with a group of friends. “Connie,” he said innocently, “I want you to meet Sheilah Graham.”

Miss Bennett measured me with a slow, insolent glance, then drawled in a voice that carried to every comer of the huge set, “It’s hard to believe that a girl as pretty as you can be the biggest bitch in Hollywood.”

There was a hush. For a moment I was a drowning woman. To lose face, to be publicly insulted and humiliated… Without thinking, fighting for my life, I heard myself say clearly, “Not the biggest, Connie. The second biggest.”

Miss Bennett was so taken aback she couldn’t think of a retort. To bridge the moment she offered me a cigarette. I said coolly, “I don’t smoke, thank you,” and pressing my advantage, I said, “Sit down, Connie, and tell me what’s bothering you.”

“Nothing’s bothering me,” said Miss Bennett, but she sat down on a bench. I sat down next to her. “Now, what did I write that you object to?”

Suddenly she regained her poise. She rose. “I never read your column,” she said icily. She turned to Milton Bren, and flung her arms gaily around him. “Oh, Milt, why do you let these strays clutter up the set?” She maneuvered him away so that I was left sitting alone. I knew I was defeated. There was nothing I could say— and even had there been, she was no longer there to hear it. I smiled a ghastly smile. I was chained to the bench: I could not leave. I felt I had to go of my own volition and in my own time. When an unhappy Milton Bren returned, I said to him, half-crying, “Do you think if I go now it will still look as if she threw me off the set?”

He said, embarrassed, “Oh, Sheilah, of course you can go. I’m so sorry—”

All the way to Malibu as I drove I repeated over and over, Not the biggest, Connie. The second biggest. Not the biggest, Connie. The second biggest. When I saw Scott I burst into tears. “This must be avenged,” he said, darkly. All evening we discussed how to get back at Miss Bennett. “What part is she playing now?” he asked. I told him she played a ghost in the latest of her Topper series. Scott recalled that Connie had attended several dances at Princeton shortly after he had left there. Together we composed a paragraph which appeared in my column the following day. I wrote, “It’s lucky no children happened to be on Constance Bennett’s set yesterday. Her language was absolutely shocking.” The next words were

Scott’s: “Poor Connie. Faded flapper of 1919 and now, symbolically, cast as a ghost in her latest production.” It was F. Scott Fitzgerald’s only contribution to Sheilah Graham’s HOLLYWOOD TODAY.

Now, finally, at Malibu, Scott let me read his three “Crack-up” articles, giving me the tear sheets from Esquire with the observation, “I shouldn’t have written these. I don’t know if I ought to let you read them, but go ahead. Tell me what you think.” He left the room.

Reading the pages I found it impossible to recognize Scott in the man who wrote so bitterly, so despairingly. This was the Scott who existed before I knew him. Writing eloquently, beautifully, he compared himself to an old plate that had cracked—one that could “never again be warmed in the stove or shuffled with the other plates in the dishpan; it will not be brought out for company but it will do to hold crackers late at night or go into the ice box under leftovers.” He spoke of the “real dark night of the soul [where] it is always three o’clock in the morning, day after day”; of a “call on physical resources that I did not command, like a man overdrawing at his bank.”

The three articles, which had appeared in Esquire in February, March, and April of 1936—only a year before we met—breathed despair and hopelessness and a kind of helpless gallantry. They spoke of “the world of bitterness, where I was making a home,” and then ended on a note of proud yet absolute wretchedness: “I will try to be a correct animal though, and if you throw me a bone with enough meat on it, I may even lick your hand.”

I walked into his room with the tear sheets. “I don’t see why you wouldn’t want me to read these, Scott. What really is wrong with them? You’re a writer. You’ve told me a writer must write the truth. This is how you felt then. But this is not you now.” They reminded me, I said, of the melancholy writing of Edgar Allan Poe. “I don’t see this as an admission of defeat but as a stage through which you passed—and one you’re not in now.”

He rubbed thoughtfully at his cheek as if to rub away an invisible spot. Edmund Wilson the critic, who had been at Princeton with Scott and whom he admired enormously, said he should not have written them. Ernest Hemingway, whom Scott had enthusiastically recommended to Scribner’s, his own publishers, had been furious with him. Both thought he had revealed too much about himself. “I don’t know if I’ll ever speak to Ernest again,” Scott said somberiy. In “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” a short story which appeared in Esquire not long after Scott’s series, Hemingway had written about one of his characters: “He remembered poor Scott Fitzgerald and his romantic awe of . . . [the rich] and how he had started a story once that began, ‘The very rich are different from you and me.’ And how someone had said to Scott, ‘Yes, they have more money.’ But that was not humorous to Scott. He thought they were a special glamorous race and when he found they weren’t it wrecked him just as much as any other thing that wrecked him.” Recalling it now, Scott grew angry. “Ernest claimed he was free to write that way about me because of what I’d written about myself. I don’t think I can ever forgive him.” He added, “That was hitting me when I was down.”

I was indignant. How callous, how patronizing Hemingway had been! Scott, a “wrecked” man? I could not think of him like that. It was utterly absurd. And in any event, Scott was right about the rich and Hemingway was wrong. This was a subject I felt qualified to speak about. I told Scott so.

“The rich are different from us, Scott. I saw it. Monte Collins was different because he was rich. So was Sir Richard. All my life I’ve seen the allowances made for the cruelties and peculiarities of a rich man. Don’t you think Monte thought himseff special and glamorous? And Sir Richard? They were different because everyone agreed they were—and because they accepted it as their right to be considered different.”

Scott laughed at that. He seemed pleased that I did not condemn him for writing as he had; and I was flattered that he valued my opinion.

Now I read his books. First, This Side of Paradise. I was disappointed. I thought its characters were young and immature. I finished it only because I knew Scott had patterned the hero upon himself. He asked, “What do you think?”

“Well,” I said judiciously, “it’s not as good as Dickens.”

“Of course it’s not as good as Dickens,” he said irritably.

I loved his short stories, and I could not say enough about his novel. Tender Is The Night. I had never read such hauntingly beautiful prose. Scott said he liked it better than anything he had written, but most people preferred his novel, The Great Gatsby. I read it and agreed with them. “I think it’s just perfect,” I said. “Everything—just the way it is.”

“You do?” he asked, pleased. “They read things into it I never knew myself.” He talked about the critics. He could not forgive them for their treatment of Tender Is The Night. Someday he hoped to rewrite it, for it should have been two books. We talked about my reaction to his work. I had judged it intellectually, not emotionally, he said. At one point he observed, “Basically you are led by your mind.”

I treasured his words.

Slowly, now, he began to tell me about Zelda. He spoke sadly, with great compassion. His confidences might be set off by a letter from her. These came on occasion, marked by brilliant, arresting language, but often little more than beautiful words strung together without meaning. Sometimes, by a letter from a member of her family reporting her progress or lack of progress. Sometimes it could be one of his letters to Scottie. He wrote his daughter frequendy—after a trip abroad she was to enter Vas-sar in the fall—and he read them to me. They were a father’s letters full of advice and concern. He tried to control her every thought, her every act, from a distance of three thousand miles. He wanted to know her grades— only A’s would do; her friends—”I don’t think so-and-so is good for you”; even the particulars of her diet—”Are you eating enough ripe fruit?” I tried to advise him, thinking, what would I have wished to hear from my father if he were ahve. Zelda and Scottie were always on Scott’s mind. When he spoke of one he found himself speaking of the other.

He had met Zelda during the war in Montgomery, Alabama, when she was seventeen, a Southern belle with red-gold hair who had every man at her feet. He was twenty-two, a lieutenant stationed at a nearby camp. He fell deeply in love with her but her family, he said, disapproved of him. He had no money and little prospects, and after the Armistice he seemed no better off, writing slogans for a New York advertising agency. “All I lived for was to save up enough money to visit her—” When he did so he found much of her time taken up by another suitor, a personable young golfer named Bobby Jones. For a time he feared that she would marry Jones. Not until Scribners accepted This Side of Paradise and he began selling to the magazines, could he win Zelda.

He brought her to New York on their honeymoon. As he spoke, I began to gain an inkling of the excitement and happiness that must have been theirs, this extraordinarily attractive young couple, she so beautiful, he so famous so young, both so much in love, both living as gaily and irresponsibly as the times themselves. She, too, was talented.’ She wrote beautifully, painted well, had aspirations to be a dancer, was an accomplished sportswoman, and in a drawing room could be as magnetic as Scott. They were the fabulous Fitzgeralds, living in a whirl of liquor, parties and gaiety—Paris, the Riviera, New York—and at the height of their popularity it was fashionable to quote everything they wrote, said, and did.

But the shadow of the future appeared early in their marriage. He began missing shirts, handkerchiefs, underwear. What had happened to his hnen? Zelda would tell him nothing. One day he opened a closet to find it piled to the ceiling with weeks of soiled laundry. She had never sent it out: she had simply tossed everything into the closet.

When Scottie was bom, it was Scott who interviewed the nurses and housekeepers and handled everything concerning their home. Though both were Hving bizarre lives, trying to “outdo, outdrink, and outwrite” each other, there came new evidences of the illness that was ultimately to crush her. One night in New York she said unexpectedly, “I want to see a dead man.” Scott, who indulged her as he indulged himself, took her to the county morgue and they spent the night going from corpse to corpse. Again, in Baltimore, Zelda announced after one of their innumerable parties, “I hate people. Dogs are better. Tm going to sleep in the dog kennel tonight.” She was as good as her word.

When they were living in Paris, in the late twenties, she suddenly took up ballet dancing. She was determined to become a member of the Russian Ballet. She studied and danced without halt. After a while it became a compulsive, terrifying thing. She danced before a mirror for nine and ten hours at a time, until she fell unconscious. “I thought I would go out of my mind,” Scott said. This phase passed. Finally, he came home one day to find her sitting on the floor, playing with a pile of sand. When he questioned her she only gave him a mysterious smile. He took her to a doctor and heard the dread words, ‘‘Votre jemme est folle.’’ Your wife is mad.

They returned to the United States, and now came the long ordeal of physicians and treatment. In a desperate attempt to keep her out of an institution, Scott hired nurses and attendants and sought to care for her in their home. It grew impossible. Though there were periods of sanity when she would be merely eccentric, he never knew when she might slip over the border and become dangerous to herself and others. Once, hearing a train, she ran toward it. Scott reached her just in time to stop her from throwing herself in front of it. On another occasion, when he invited a young writer to their home, Zelda came into his study as the two men stood together, Scott with his arm around the others shoulder, reading a manuscript. Scott was pointing to a sentence. “Bill, I’d change this to read—” Zelda came up silendy behind them, put her hands to Bill’s face and raked his cheeks with her nails. He broke away, bleeding, to stare at her in horror. Scott led her into another room. She had always been jealous of his friends, particulary if they were writers.

Ultimately, because there was no other way, he sent Scottie to a boarding school and placed his poor Zelda in a sanitarium in Asheville, North Carolina. Here he came on his visits from Hollywood, taking her out for a few days each time. Once, feeling she was better, he planned a perfect afternoon for her—a pleasant drive and a quiet lunch at the home of old friends. To make certain that nothing would upset her, he asked that no one else be invited. He hired an open car and drove Zelda, wearing a bright red trailing dress of the twenties —she seemed to prefer such clothes, apparently associating them with her happy years—down the mountains from Asheville to their host’s home in nearby Tyron. At the beginning of the meal Zelda was herself—alert, warm, charming. But half way through, a change came over her. Before their eyes she began to withdraw, to fade, to vanish from their midst though she still sat there; and by the time coffee was served, she was in a world of her own, remote and unreachable. Miserably, Scott drove her back to the sanitarium. On the way she wrenched open the door and tried to leap from the moving car. For some time after that he made no attempt to take her from the institution. Instead, when he visited, they played tennis, which was beheved good therapy, or he watched from the sidelines while she tried a set or two with one of the doctors. On one occasion, losing a match, she suddenly turned on her partner and belabored him over the head with her racket.

Then came the time Scott took her to New York for a week end. It was here she tried to have him committed. The morning after their arrival he woke in their hotel room to find Zelda gone and his pants missing. He tried to ring the desk clerk: the switchboard was dead. He went to the door; it was locked. After a few minutes of almost nightmare horror he got through to the clerk. “Now, take it easy, Mr. Fitzgerald,” the latter said soothingly. “A doctor is on his way.” When the physician arrived with two cautious bellboys as reinforcement, Scott discovered that Zelda had told everyone her husband was insane, that she was permitted to take him out of the sanitarium only at intervals, but now he had suddenly become violent and must be taken back at once. After Scott managed to convince the doctor that it was Zelda who was ill, the two men set out in search of her. They found her in Central Park digging a grave in which to bury Scott’s pants.

This, in essence, is what Scott told me, little by little, reluctantly as though compelled to do so, as though in the telling the intolerable weight on him was somehow lessened. I tried to be of comfort. At one point he said,

“She would never bend. That is why she broke. You know how to bend.” And then, dispassionately, “We would have been better off had we married somebody else. We were bad for each other.”

My reaction was strange. I began to brood. For hours I would sit in a chair, facing a window looking out on the sea, motionless, saying nothing; thinking, what am I doing here? I had gotten a divorce from Johnny so that I could be free to marry; I could have been a marchioness; my child might have been on its way even now. But, no. I had fallen in love with a man I could not marry. He was married to a woman he could not divorce. Now, in truth, knowing this much about Zelda, knowing his pity and compassion for her, I knew he could never, he would never, divorce her. We were both helpless, Scott and I.

Scott, working in his room, would wander downstairs to see what I was doing. It must have frightened him to find me sitting there, without moving a muscle, staring straight ahead. It must have reminded him of Zelda’s brooding. Suddenly I was far away and he could not reach me, he could not foUow me.

“Dear—” he would begin.

I made no reply.

Then, “Dear, is there anything the matter?”

“No.” I stared straight ahead.

“There must be—you look so sad.”

“No. There’s nothing the matter.”

Silence.

“Perhaps—” He was very gentle. “Perhaps if you took a walk along the beach you’d feel better.”

“No.” I still did not turn my head.

“Well . . .” His voice died away. Then, almost apologetically, “I’ll go up and finish some work.”

I would hear him mount the stairs and still not look in his direction. I was held in a strange spell, a coma, an almost physical paralysis. I was punishing him for not being able to marry me. Yet there was nothing he could do about it. Nor I. I could leave him—but it was impossible for me to imagine life without him. There was nothing to protest; there was nothing to be done; this was the normal injustice of life. We were two helpless people who happened to meet each other.

And hearing Scott pace, back and forth, knowing he was not working, I wept. For him. For me. For his poor Zelda.

Next chapter 21

Published as Beloved Infidel by Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1958).