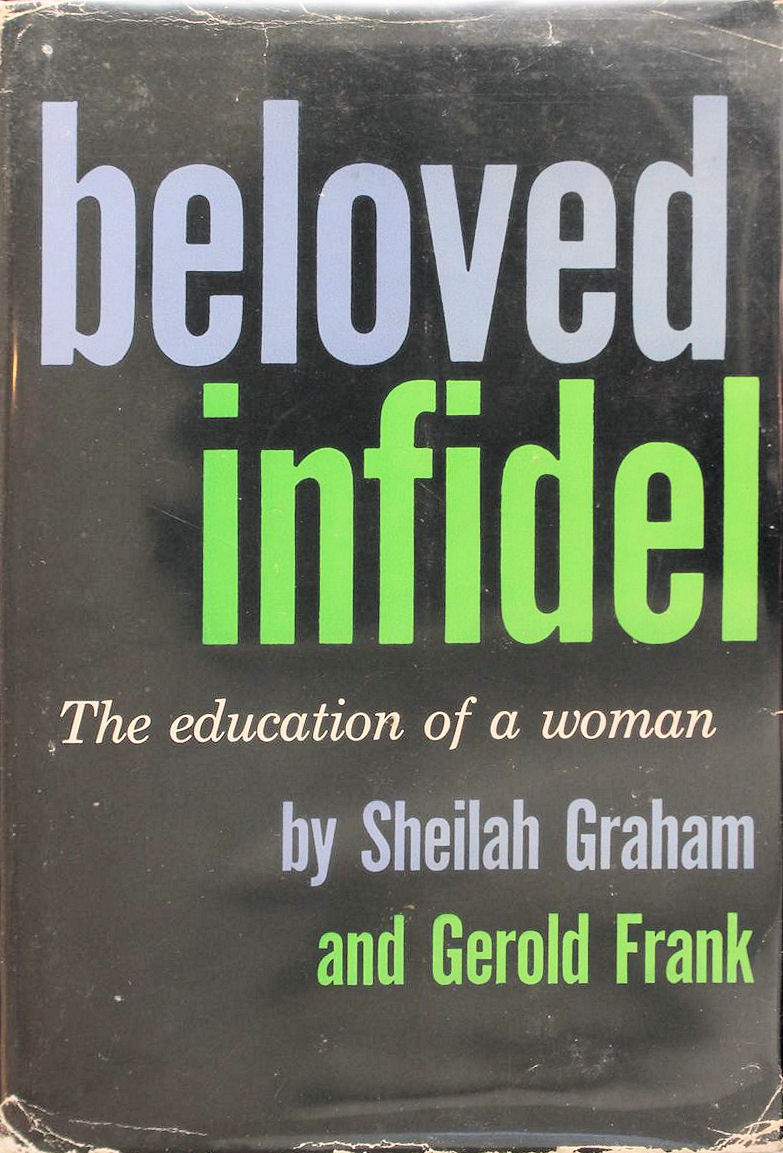

Beloved Infidel: The Education of a Woman

Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

I SAID, remembering to choose my words very carefully, “How d’you do.” Gracefully I gave my hand to the dazzlingly handsome young man who bowed over it.

Tom Mitford had introduced us. “Sheilah,” he had said. “May 1 present my cousin, Randolph Churchill.”

We were at Quaglino’s, where Johnny had taken me months before on the night of my presentation. I had heard from Tom and Jock and other Etonians, a great deal about Winston Churchill’s briUiant and arrogant son. Now in his early twenties, he was already a legend. His conceit, I had heard, had made him one of the most unpopular students at Eton and Oxford. But at this moment, as he joined us for a drink, I saw no arrogance, only charm in this extraordinarily attractive young man. He was tall, slim, with aristocratic features, a fresh, ruddy complexion, and soft brown hair. He and Tom had fun at my expense. Tom said, “Actually, I’ve always rather wondered about Mr. Gillam. He seems to be something of a mystery. I don’t believe there is a Mr. Gillam—is there, Sheilah?” I smiled prettily and said nothing.

I watched .Randolph with awe then and later when I grew to know him better. For all my admiration of the elite, I realized that those I had known were not intellectuals, nor had any desire to be. Randolph represented my first brush with brains among the upper classes— and it was disconcerting, for I discovered that he had nothing but contempt for most of the things I revered.

Randolph and Tom lunched together often; their table at Quaglino’s was a rendezvous for politically conscious young men, and I was a frequent guest. I was introduced to a red-haired man with freckled skin and thick glasses, Brendan Bracken. They spoke eagerly of the time Winston Churchill, currently the unsuccessful M.P. for Ep-ping, would return to power. The country needed him desperately, Randolph said.

Someone mentioned ex-premier, Stanley Baldwin. Randolph snorted. “An idiot—an imbecile!” He sneered at Ramsay MacDonald. He and the others spoke slightingly of several members of the House of Commons. Listening to Randolph’s words of contempt for Ramsay MacDonald, I thought, it doesn’t really matter what you achieve—it doesn’t matter that you’re clever and always at the head of your class. What matters is that you’re not of gentle birth. That damns you forever, even if you become prime minister of England. It’s marked on you Hke a tattoo. You can’t erase it. You may try and some people may not see it, but others will—no matter how invisible it becomes. And you never know when you will meet those who can see it.

Tom Mitford went on holiday to Munich to spend a few days with his sister, Unity, attending finishing school there. Randolph began taking me to dinner at Quag’s. One evening his guests included Charles Chaplin. My awe at meeting so great an artist was dispelled by Chaplin’s astonishing obsequiousness to Randolph. “Of course, you’ve always had the advantages,” Chaplin was saying. “I haven’t. I’ve had to fight for everything I have.” He told almost apologetically, of his childhood, his early poverty, his struggles as a music-hall entertainer. “How lucky you are to have been bom with the name Churchill,” he went on. “To be bom to wealth and position.” These were my sentiments, too, but to hear Chaplin express them shocked me.

Randolph was most condescending. “Oh, well, you’ve worked hard to get where you are—I wouldn’t think my way of life is any better.”

Chaplin shook his head. I grew furious. Why does he feel inferior to this patronizing young man? If I was awed by high society that was understandable, for I was an imposter in everything I did. But Chaplin was a genius! How dared he humble himself!

The conversation turned to Ramsay MacDonald’s political party and Chaplin began a long analysis of Mr. MacDonald’s problems. Randolph intermpted him. “Oh, Charlie, for Heaven’s sake shut up! You don’t know what you’re talking about.” He leaned insolently across Chaplin without so much as I-beg-your-pardon to stub out a cigarette in an ash tray. “Let’s talk about things you know. Tell us about Hollywood, Charlie.”

Chaplin took the rebuke without protest. Now he spoke brilliantly about the movie colony in America. I began to think, how wonderful it must be to live in America where people take you at face value. Americans don’t think about your birth or upbringing. Indeed, they admire you if you dare climb upward, if you aspire to be rich, important, and successful.

Leaving the restaurant we waited in the foyer for Randolph’s car. A crowd gathered to stare at Chaplin.

He rewarded them with a bit from his famous tramp act —his little, splay-footed run, ending in an off-balance teetering on one foot. The crowd applauded.

I went back to Johnny. “You met Charles Chaplin!” he exclaimed. “Fancy that! You dining with Charles Chaplin!”

I thought, perhaps one should never come too close to a celebrity. It was a lesson I would learn far more effectively in Hollywood.

Tom Mitford, back from Munich, could talk of only one subject. “I’ve met the most fascinating man in my life!” he exclaimed. “Absolutely amazing. Sweeps you off your feet when he speaks! The most persuasive man I’ve ever met.” It was Adolf Hitler. Randolph said scornfully, “That little man with a mustache—don’t be ridiculous, Tom.” But Tom spoke on. Unity, with fervent admiration, had introduced him to Hitler—all Germany would follow him, and very soon too, she insisted. They had both been invited to Hitler’s home. It had been a remarkable experience. Of course, some of Hitler’s ideas were shocking, yet—Tom and Randolph began a long ‘debate about the historical role of democracy and fascism.

I had no idea what they were talking about, although I had read about Hitler, too. When they discussed such matters, or went on to argue about the Japanese march into Manchuria, or other affairs of which I was completely ignorant, I smiled and listened and smiled. No one deigned to ask my opinion, nor did I venture one. I was there to be decorative. I wore my smile like a mask to hide my inadequacy, and was grateful that they expected nothing from me.

Yet I returned from such luncheons fuming at myself. I would hurry to the International Sportsman’s Qub to take out my frustration on the squash court. I had become extremely adept, so that I was a member of the ladies’ squash team. I played furiously, practiced furiously. Sometimes Jock or Judith would say, “Sheilah, why do you play so hard? It’s only a game.” But they could not understand that when I played squash, it was one of the few times I was not engaged in pretense.

Smashing that little black ball T felt free, I felt co-ordinated and superior, I felt whole and honest.

Day after day, when I would practice, I would notice the captain of the men’s team practicing with equal diligence. He was the Marquess of Donegall, who belonged to one of the most ancient peerages in the British Isles. Lord Donegall enjoyed trying his hand at journalism. His column on society appeared each week in the Sunday Dispatch and I followed it religiously to keep informed.

I admired his lordship from afar. He lived in a world of fun, titles, and money, traveling constantly, staying in France, Italy, and Spain with the Due de this and the Earl of that. Now and then I saw him come into Quaglino’s with a party of friends, the waiters bowing and scraping before him as he made his way to his table. He bore such exalted titles. He was Marquess and Earl of Donegall, Earl of Belfast, Viscount Chichester of Ireland, Baron Fisherwick of Fisherwick, Hereditary Lord High Admiral of Lough Neagh, and half a dozen others.

We both finished practice simultaneously one day, and met as we emerged. “Well,” he said. “I’ve been watching you. You play a good game.” He invited me for a cocktail. “How is it that I haven’t met you before?”

“Oh, I travel quite a bit,” I said vaguely. Donegall had reason to ask, for he knew everyone. He was about twenty-seven, a slender, attractive man, delicately turned out, with dark brown hair, impeccably groomed, large brown eyes—enormously sympathetic, and small, gentle hands. He was boyish, he^laughed readily and I listened as he talked. “Tomorrow I’ve promised to go to the Plunketts and on Thursday, Westminster has asked me to Scotland—” He reeled off the enchantments I’d read in his column and which I had only begun to taste.

I set my cap for Lord Donegall. Following a squash tournament a week later, a small party was given for members of the ladies’ and men’s teams. I wore a pretty little skirt and red sweater. Lord Donegall entered the room and looked around. Our eyes met: I smiled at him. He made his way over to me and perched on the arm of my chair. How had I come out with my game?

“Oh, I won.”

“Excellent!” he said. He had won his match, too. I said, “You know, you’re a friend of a friend of mine—Tom Mitford.” We talked about Tom. I went on, “Do you know Dennis Bradley?” naming another of Jock’s Oxford friends. He nodded. “Are you going to Dennis’ cocktail party next week?” I asked. He looked down at me. “Are you?” “Yes.”

“Then I am,” he said, with a smile. I went to Dennis Bradley’s party alone, and Lord Donegall accompanied me home. Johnny had gone that night to one of his regimental dinners; he would feel middle-aged, he complained, in a group of dashing young people. His lordship arranged to lunch with me on the following day.

That began our friendship. I told him enough about myself to make clear that I was a young society matron with time on my hands. Had I been Miss Graham and not Mrs. Gillam, Donegall would have wanted to know about my family, my schooling and other details. Now, instead, we talked about mutual friends and shooting in Northumberland and skiing in Switzerland. He was intrigued to learn that I had been on the musical-comedy stage, and impressed that I had sold an article to a newspaper.

We got along famously. In the months that followed, he escorted me to many social events. I was his guest at Ascot, and accompanied him to a fashionable boating party on the Thames. We spent hours driving through the countryside; and presently Donegall said, “I’m in love with you, Sheilah. I want to marry you.” “Oh, Don!” I said. I took it as a joke. I was not in love with hun. And who could conceive it—Lily Shell, Her Grace, Marchioness of Donegall? My son would be the Earl of Belfast, my daughter, the Lady Wendy Chichester! No, I’d never be able to carry off anything like that. I said, “I already have a husband, you know.” He said, “You have heard of divorce—” I laughed. “Don, you don’t really mean it. Besides, your mother wouldn’t approve.” It was well known that the Marchioness of Donegall was most unapproachable where her son was concerned.

He said lugubriously, “You may be right.” Then he smiled. “But don’t forget I asked you.”

Perhaps it was the stimulation of Randolph Churchill’s table at Quag’s which led me to try writing again, to reassure myself there was more to me than a smile. Or perhaps Lord Donegall’s proposal, far-fetched as it was, had made me question again my marriage to Johnny. But one afternoon I sat down and without a thought for A. P. Herbert’s rules of composition I dashed off an article entitled, “ ‘I Married a Man 25 Years Older,’ by a Young Wife.” I sent it to the Sunday Pictorial. They bought it. When they gave me my check, I saw with amazement that it was for eight guineas.

I walked slowly out of the Pictorial offices into Fleet Street. The narrow, busy thoroughfare was half-deserted now. It was twilight. I walked down Fleet Street in the twilight, repeating to myself, in wonder, “With this brain, from nothing I have made eight guineas!” I thought, this is my real career. A newspaper woman. This is how I shall become rich and famous.

On impulse I sent a letter to The Saturday Evening Post, which I’d heard was America’s most popular magazine, asking if there were any articles I might send them from England. I enclosed tear sheets of my articles. While I waited, the Daily Mail bought a second piece of mine: “ ‘Baby or a Car,’ by a New Bride.” I said a car, knowing this would cause the greatest comment.

My inquiry to the Post brought a tentative assignment to interview Lord Beaverbrook. J. B. Priestley, the British author, had written a scathing attack on America as ignorant and boorish—this, after returning from a lucrative lecture tour of America. It had infuriated everyone in the United States. What was Beaverbrook’s opinion of his fellow countryman who repaid American hospitality—and money—in such unsporting fashion?

I sent in my request for an interview with Lord Beaverbrook. Word came back. “Lord Beaverbrook is not available.” He had gone to his country estate, Cherkley Court, about fifty miles from London. I set out in pursuit of him. At Cherkley Court, a butler barred my way. When I insisted that he must take in my message, he returned to say, icily, “His lordship will not see you.” He closed the door in my face.

Next day I went again to Cherkley Court, and again the impassive butler barred the door. “He has to see me!” I almost wept. This time the message came back, “Lord Beaverbrook says that such persistence should be rewarded. He will see you in town tomorrow afternoon at two o’clock.”

When I presented myself at Beaverbrook’s town house, I was ushered into a huge reception room dominated by the portrait of a strikingly beautiful woman. Suddenly a door opened and a little, gnomelike figure bounded into the room. I was conscious of a big head, sharp eyes, and an enormously wide, expressive mouth. It was Lord Beaverbrook. He saw me looking at the portrait. “That’s my wife,” he boomed. “Isn’t she beautiful?”

I managed to nod. In the presence of that compressed, springlike energy, I felt drained of my own strength. His lordship appeared ready to explode any moment from sheer vitality. Without preface he said emphatically, “No, Miss Graham, I won’t give you the interview you want. Priestley writes for ine and I’ll not speak against my own writers. If he doesn’t like America, that’s his business. But look here—I’ll give you a better story.” He led me to a sofa. “I’U tell you why the League of Nations should be abolished. I’ll write it for you and you can say you wrote it. Take it to the Hearst papers here and they’U pay you twenty pounds for it.”

I sank back into the cushions thinking, isn’t this marvelous! What an auspicious way to begin my new career! The sun made bright patterns on the enormous Persian rug covering the floor. Beaverbrook gazed at me. Again, suddenly—he shot words at me hke bullets from a gun, “Do you ride?”

A little taken aback I replied, “Yes, Lord Beaverbrook.”

“Care to ride with me this afternoon at Cherkley?” he demanded.

I said, weakly, I’d be delighted. Yes, I had riding clothes at home, not too far away. I thought, this is simply fantastic. One moment I’m begging at his door, the next he’s inviting me to ride with him. This is even better than getting the interview!

He leaped up, bounded to a desk and pressed a button. “My chauffeur will take you home to pick up your riding things. Don’t be long now!”

An hour and a half later we were on two beautiful horses riding along a quiet lane in his forest at Cherkley. He said, as we chatted, “By the way, I want you to meet Mrs. Robert Carter.” 1 looked at him, puzzled. We were alone. He chuckled. “You’re riding her.”

“You mean this horse?” I asked, uncertainly.

He nodded. “And this—” he patted the shoulder of his mare. “This is Lady Kitty Wallace.”

I giggled. “What unusual names for horses!”

A puckish grin played over his face. “All my horses are named after my favorite ladies.”

I considered this for a moment. It sounded outrageous but I wasn’t sure. “Well,” I remarked lightly, wondering whether I was saying more than 1 meant, “I hope you’ll name a horse after me one day.”

He rubbed his cheek with the butt of his riding crop. “Perhaps I shall,” he said, with another grin. Then he began talking about himself. He talked incessantly, explosively, as we rode. He talked about his father, who had been a poor man in Canada. He told me about his wife’s death, that but for his little granddaughter, Jean, he lived alone, and how ridiculous it was that he should have forty servants to wait upon him. Now and then he asked me questions but he rarely gave me time to reply. When we had finished our ride, he said, “Of course, you’ll have dinner and stay over? We dine rather late.”

I was in a dilemma. The best way out was to tell the truth. “I’d like to. Lord Beaverbrook, but I must call my husband and tell him.”

A shade of irritation darkened his face. “Oh, you’re married!” He said it sharply. “Of course, call him.” He led the way to a telephone. But I felt him withdrawing. I got Johnny on the wire and for the first time Johnny, who 1 thought would delight in this coup, proved difficult.

“Are you sure it’s all right for you to stay down there?” his voice came back. Beaverbrook stood nearby, tapping his finger impatiently. 1 looked at him as 1 spoke into the mouthpiece. “Of course it’s all right, Johnny.” But Johnny wasn’t satisfied. “Is there someone there?” he demanded. “Can’t you speak freely?” I was furious. I wanted a good interview. There were other guests at dinner. “Johnny, Lord Beaverbrook is right here. Everything is perfecdy all right.” So Johnny acquiesced. But when I put down the phone, Beaverbrook had withdrawn considerably.

After dinner we adjourned to a small auditorium where Beaverbrook prepared to show the latest American films to his guests. As we sat waiting, a footman entered and whispered in his ear. Lord Beaverbrook turned to me. “The car is ready for you,” he said.

I was sent back to London. I rode back ahnost in tears, consoling myself with the interview he had promised to write for me. But when it came, I read the manuscript with growing consternation. Beaverbrook, writing as Sheilah Graham, described how I had waited for him to return from a ride in the forest. When he finally appeared, astride a horse, my first impression had been, this is Napoleon. For the man I gazed upon had the same air of conquering his destiny. This continued for three pages, closing with a demand that the League of Nations be abolished. He had printed the demand in his newspapers weeks before.

I thought, this is rubbish. Nobody will pay money for this. I was right. Nobody did. When I told Beaverbrook I could not sell it to the Hearst editors, he sent me his own check for twenty pounds. “Tell them to forget it,” he said.

A few days later, a hearty voice rumbled over my telephone. It was Lord Castlerosse, one of Beaverbrook’s popular columnists. “I’ve heard about you bearding Max in his home. Very clever! I’d like to meet you.” Would I have lunch with him?

Over lunch he said, “I know all about that League of Nations story—I have a far better idea for you.” His suggestion was for me to do a story on the four “Paper Lords” of England: Lord Beaverbrook, Lord Rother-mere, owner of the Daily Mail; Lord Riddell, owner of News of the World; and Lord Camrose, who owned the Daily Telegraph. “You can sell that to any American magazine and make a name for yourself,” he assured me. “I’ll help you.” He would go so far as to write the section dealing with Beaverbrook and tell me where to obtain information on the others.

This was a major article compared to the flippant pieces I had written up to now. I jumped at the chance. Lord Castlerosse kept his promise. His section on Beaverbrook was witty and sardonic. One sentence read: “As a child I had a rubber doll, broad of face and mouth, and when I squeezed its middle, out went its tongue. That doll was like Lord Beaverbrook; and, as with rubber, you never quite know how far he will go.” I toiled over the remainder of the piece. It sold to Nash’s magazine for twenty-five guineas and created a considerable stir. I was a magazine writer!

In return, Lord Castlerosse required a favor of me. He had been left by his wife, whom he adored. I was to visit Lady Castlerosse and introduce myself as a reporter assigned to write about her friendship with a South African diamond millionaire. Lord Castlerosse counted on the threat of exposure to driver her back to his arms.

Hating myself, hoping that she would refuse to see me, I called on her. But when 1 was announced and the purpose of my visit made known, she came down so swiftly you could hear the swish of her gown. She said, aghast, “Oh, you can’t write about that!”

I felt utterly ashamed. It was despicable to do this to another woman. But my visit achieved its purpose: she returned to her husband. I had made a friend of an important man but at a revolting cost. It taught me an old truth which I had long tried not to believe—you rarely get anything for nothing.

Now I, instead of Johnny, haunted the library researching material for articles. I studied American newspapers and to my astonishment often came upon the same article in a dozen different papers. I asked Lord Castlerosse how this was possible. “Syndication,” he explained. America had hundreds of newspapers, each serving its own locality. Instead of selling your article to one newspaper, you sold it to fifty or a hundred—and your payment increased proportionally.

I thought, this is wonderful: this is the answer to everything. I must go to America. I won’t have to carry the burden of my past so consciously there: I can support myself and stand on my own feet. At least, I could try.

The more I thought about it, the more attractive the idea seemed. I could go to the United States as an English authoress who had given up the boredom of high society for a career. I would sell a woman’s column to American newspapers. Obviously, I had a flare for writing on subjects of interest to women—love, marriage, men. I knew a great deal about men. I had studied them almost to the exclusion of women. I believed I had gained a great knowledge of human motives—of Life.

When I broached it to Johnny, he took fire, too. “You go first and then I’ll join you,” he said. He had his job to keep. He knew I could do better alone, for I was young and pretty and there would be many helping hands. If my middle-aged husband came along, nobody would want to help me.

And so it was agreed.

But I realized that this marked the end of our marriage. If Johnny realized it, he said nothing. Though I knew I could never really give up Johnny, any more than one could give up one’s parents—he would always be my family—I knew that I could not remain Mrs. John Gillam much longer. Somewhere I must find love again.

Next chapter 14

Published as Beloved Infidel by Sheilah Graham and Gerold Frank (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1958).