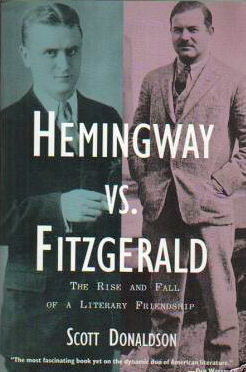

Hemingway vs. Fitzgerald: The Rise and Fall of a Literary Friendship

by Scott Donaldson

Chapter 5

1929: Breaking The Bonds

It is well, when judging a friend, to remember that he is judging you with the same godlike and superior impartiality.

—Arnold Bennett

During much of 1929—a year in which the Jazz Age and the stock market and a good many other things came crashing to earth—the Hemingways and Fitzgeralds were living in Paris, in the same neighborhood. They saw little of each other, for that was the way Ernest wanted it.

With A Farewell to Arms delivered to Perkins for serialization in Scribner's magazine and fall book publication, Hemingway sailed for France on April 5. “If you see Scott in Paris write me soon how he is,” Max wired Ernest at the boat. As a friend Perkins worried about Fitzgerald's deteriorating condition, and as a publisher he had an understandable interest in the novel Scott had been promising since 1925.

Scott was already in Europe when Ernest embarked from New York. He and Zelda had crossed on the Conte Biancamano in March, landing in Genoa and working their way across the Riviera before going to Paris. As in 1924, the Fitzgeralds hoped that a change in scenery might alter the disturbing rhythm of their stateside lives. At Ellerslie Zelda became increasingly obsessive about the ballet, forever practicing before a mirror to “The March of the Toy Soldiers.” She thought Philippe rude and insubordinate, and further trouble developed when Mademoiselle Delplangue—Scottie's nanny—fell for Philippe and became “hysterical” about it. When he wasn't drinking, Scott wandered around the property or worked on his Basil Duke Lee stories—anything to avoid the novel. One difficulty, as Perkins intuited, was that he had chosen the almost forbidden subject of matricide as the basis of his plot. The Boy Who Killed His Mother was the working title, with the protagonist a Hollywood cameraman bearing the unlikely name of Francis Melarkey.

In November 1928 Fitzgerald sent Perkins the first two chapters of this false start, which was after five more years to segue into something very different. “My God it's good to see those chapters lying in an envelope!” he said. They ran to 18,000 words, and constituted the first quarter of the book. He planned to send Max the rest of the novel in three additional two-chapter segments. Chapters 3 and 4 should be on their way in December.

The deadline came and went, and early in March Fitzgerald apologized to Perkins for “sneaking away like a thief without leaving the chapters.” They could be straightened out with a week's work, he estimated, and he could complete them on the boat. Instead he wrote a story called “The Rough Crossing,” in which the husband-and-wife principals—who resemble himself and Zelda— become involved in shipboard parties that lead to drunkenness and adultery.

Hearing that Fitzgerald was coming to Paris gave Hemingway “the horrors,” he wrote Perkins. On no account was Max to give Scott his address. He and Pauline had found a quiet and comfortable apartment on the rue de Férou, and were afraid that Scott would misbehave and get them ejected. According to Ernest, Scott had already got him kicked out of one apartment the “[l]ast time he was in Paris”: a reference, apparently, to the flat he and Hadley occupied on the rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs in 1926. Then too, he and Zelda were given to turning up intoxicated and banging on the door in the wee hours. “I am very fond of Scott,” Ernest assured Perkins, but he was prepared to beat him up—“as a matter of fact I'm afraid I'd kill him”—before he'd let him get them “ousted” from their apartment. It had nothing to do with friendship, for that implied “obligations on both sides.” The “both sides” phrase connoted a view of friendship as a competitive, if not adversarial relationship.

Despite Ernest's vigorous warnings, the Fitzgeralds and Hemingways did get together in Paris that spring. They could hardly have helped running into each other. The Fitzgeralds rented an apartment on the rue Palatine, only a block around the corner from the rue de Férou, and Scottie was taken to mass at St. Sulpice, the Hemingways' parish church. There was even a dinner at the Hemingways' apartment, where, Scott observed, the atmosphere was tainted by a “[c]ertain coldness.” In a list of snubs, he recorded two from 1929: “Ernest apartment” and “Ernest taking me to that bum restaurant.Change of station implied.” The strain was evident in the artificial hilarity of a dinner invitation Scott sent Ernest in May: “Will you take salt with us on Sunday or Monday night? Would make great personal whoopee on receipt of favorable response.”

Scott summarized that unhappy time in a personal history written after Zelda's mental collapse. They had been living in Delaware in a state of unhappiness and at a prohibitively expensive rate, he wrote, but upon leaving for Paris

…somehow I felt happier. Another spring—I would see Ernest whom I had launched, Gerald & Sara who through my agency had been able to try the movies [Fitzgerald introduced the Murphys to the director King Vidor]. At least life would [be] less drab; there would be parties with people who offered something, conversations with people with something to say….

It worked out beautifully didn't it. Gerald and Sara didn't see us. Ernest and I met but it was a more irritable Ernest, apprehensively telling me his whereabouts lest I come in on them tight and endanger his lease. The discovery that half a dozen people were familiars there didn't help my self esteem.

A Farewell to Criticism

“I'm delighted about Ernest's novel,” Fitzgerald wrote Perkins early in April, adding wryly that he himself would be “trying as usual to finish mine.”

It was not until late May that Fitzgerald saw the typescript of A Farewell to Arms. The novel was then running as a six-part serial in Scribner's magazine, but changes could still be made before actual publication of the book. It is unclear whether Hemingway asked for editorial comments, or whether Fitzgerald volunteered them. Unlike the situation three years earlier, when he cut the beginning of The Sun Also Rises at Scott's behest, Ernest was neither pleased with the criticism his friend provided on Farewell, nor inclined to accept his judgments. He had progressed in his craft, after all, while Fitzgerald's creative engine had stalled. He no longer required Scott to find him a publisher or to intervene on his behalf with Max Perkins. For the most part, he was right to ignore Fitzgerald's suggestions.

If anything, Fitzgerald was even more severe in his comments about Farewell than he had been in discussing Sun. He attempted to soften the blows in two ways. First, in recommending alterations, he pointed to Hemingway's own previous work as the standard of excellence. Ernest wasn't really listening to his heroine Catherine Barkley in the same way he had to the women characters in “Cat in the Rain” or “Hills Like White Elephants,” Scott argued. Nor did some of the scenes in Milan come up to the quality of the fishing trip in The Sun Also Rises, where introduction of the seemingly extraneous Englishman Wilson-Harris contributed “to the tautness of waiting for Brett.” Second, Fitzgerald balanced his faultfinding with praise, especially near the end of his comments, finishing with the exclamatory “A beautiful book it is!”—an observation that elicited a handwritten “Kiss my ass” in the margin from Hemingway.

Fitzgerald suggested extensive cuts for Farewell, just as he had in connection with Sun. (He made no comments whatever about the first third of the book: Hemingway may have told him to ignore the beginning chapters.) Fitzgerald recommended excisions, particularly, in the scenes that took place during the period of Frederic Henry's recovery from his war wounds in Milan, and in scenes where he and Catherine conducted their most intimate conversations.

One of the Milan scenes Fitzgerald objected to involved Frederic's afternoon conversation with the two American singers trying to break into Italian opera and with the war hero Ettore Moretti. The passage was slow, Scott thought, and included too many characters and too much talk. “Please cut!” he pleaded with Hemingway. At the very least, he should reduce the “rather gassy” half-dozen pages to a brief and self-sufficient vignette.

There was “absolutely no psychological justification” for introducing those singers, Scott asserted. There was, however, a strong structural justification for bringing Simmons, one of those singers, onstage, inasmuch as it was to be Simmons that Frederic went to see—and to borrow civilian clothes from—when he made his escape to neutral Switzerland. Similarly, the apparently irrelevant Moretti plays an important thematic role in illustrating the consequences of the war. Nothing good could come of it. The only ones who stood to profit were boring and conceited killers who like Moretti bragged endlessly about their battlefield exploits. Ernest had summed up his own views on the subject in an October 1918 letter to his family from the hospital in Milan. “There are no heroes in this war… All the heroes are dead.”

In proposing this excision, Fitzgerald was considering the scene in isolation instead of as part of the overall fabric of the novel. In his concentration onthe trees, he did not see the forest. The same was true of the other seemingly unnecessary scene Scott recommended cutting: the day at San Siro (Chapter 20) that is ruined for Catherine and Frederic by the discovery that the horse races were fixed. “This is definitely dull,” Scott wrote. If it were up to him, he'd cut it in half and move it to the beginning of the next chapter. Again, considered by itself the racetrack scene is not particularly effective. But when tied into Farewell's pervasive theme of a corrupt world that confounds and defeats the individual, the fixed races convey an important message.

Significantly, the one cut Hemingway actually made among the half dozen proposed by Fitzgerald worked to maintain the novel's suspense. The passage consists of an extended rumination by Frederic in Chapter 40, the penultimate chapter, on the comparative risks of sacred and profane love. The contrast between these two kinds of love constitutes a major theme of the novel, first developed in the opening chapters, and so it made sense to deal with it again toward the end. But with a nudge from Fitzgerald, Hemingway decided against including this passage. It was too long, and it gave away what was going to happen at the end of the book. Here is the excised section, in part:

…They say the only way you can keep a thing is to lose it and this may be true but I do not admire it. The only thing I know is that if you love anything enough they take it away from you. This may all be done in infinite wisdom but whoever does it is not my friend. I am afraid of God at night but I would have admired him more if he would have stopped the war or never let it start… And if it is the Lord that giveth and the Lord that taketh away I do not admire him for taking Catherine away…

I see the wisdom of the priest at our mess who has always loved God and so is happy and I am sure that nothing will ever take God away from him. But how much is wisdom and how much is luck to be born that way? And what if you are not built that way? What if the things you love are perishable?…

The unfortunate disclosure here is that Catherine is about to die.

Among the characters in A Farewell to Arms, it was Catherine that Fitzgerald came down hardest on. He particularly disliked the scene in Chapter 21—Hemingway, in reading over this commentary, could hardly have avoided noticing that Fitzgerald was advocating overhaul of three consecutive chaptersin a novel he had already written and revised to his own satisfaction—where Catherine hesitantly reveals and apologizes for her pregnancy. Many critics have found Hemingway's heroine impossibly noble and self-sacrificing in her desire to please her lover at whatever cost. Fitzgerald, as the first of these critics, counseled extensive deletions as a remedy.

“This could stand a good cutting,” he observed about Chapter 21. “Sometimes these conversations with her take on a naive quality that wouldn't please you in anyone else's work. Have you read Noel Coward?” (Fitzgerald's endorsement of the urbane British playwright Coward, whose characters speak a witty café society dialogue, must have bothered Hemingway.) Then Scott went on versus Catherine. “Remember the brave illegitimate mother is an OLD SITUATION & has been exploited by all sorts of people you won't lower yourself to read.” Under the circumstances, Ernest should make sure that “every line rings new.” Scott was not through with his critique. “Catherine is too glib… In cutting their conversations cut some of her speeches rather than his.” The trouble was that Ernest, in recalling his own wartime wounding and love affair, was still seeing the nurse through idealizing “nineteen yr. old eyes” while looking back on himself in a more sophisticated way. The contrast jarred: “either the [narrator] is a simple fellow or she's Eleanora Duse disguised as a Red Cross nurse.”

Once again, Fitzgerald underestimated the secondary importance of one of Hemingway's scenes, this time for its revelation of character. In reluctantly confessing her condition and offering to take care of all arrangements on her own, Catherine is indeed almost incredibly accommodating—or would seem so were it not for her fragile emotional state, having lost another “boy” she loved to the war. But the scene is crucial in uncovering Frederic's lingering self-absorption and his unwillingness, at this stage, to commit himself fully to Catherine. Upon hearing her news, he says nothing to comfort or reassure her, and more or less forces her to continue talking: ergo, the relative silence that Fitzgerald would have remedied. And when she finally asks him if he feels trapped, Frederic responds with the callous comment that “You always feel trapped biologically”—as if he had impregnated any number of women and invariably felt “trapped” afterwards.

In his critique, Fitzgerald twice objected that the war kept receding from the foreground of the novel. The book became dull during the episodes in Milan, he thought, “because the war goes further & further out of sight every minute.” The ending troubled him for the same reason. “Seems to me a last echo of the war very faint when Catherine is dying and he's drinking beer in the Cafe.” When Ernest turned his attention directly to the war, as during the retreat fromCaporetto, the result was “marvellous.” The scene of Frederic's arrest by the self-righteous battle police, and his dive into the Tagliamento to escape, was “the best in recent fiction,” Scott thought. But he did not like the actual ending as it then stood—a roundup of what happened to various characters in the years since Catherine died, culminating in a valedictory paragraph:

I could tell you what I have done since March, nineteen hundred and eighteen, when I walked that night in the rain back to the hotel where Catherine and I had lived and went upstairs to our room and undressed and slept finally, because I was so tired—to wake in the morning with the sun shining in the window; then suddenly to realize what had happened. I could tell you what has happened since then, but that is the end of the story.

Fitzgerald suggested instead that Hemingway finish with Frederic's eloquent soliloquy the night after he and Catherine are reunited in Stresa. The passage celebrates their love, which now had become strong enough to survive any shocks short of death. “Often a man wishes to be alone and a girl wishes to be alone too and if they love each other they are jealous of that in each other, but I can truly say we never felt that. We could feel alone when we were together, alone against the others.” Then too, they loved each other at night just as they did during the day. “[T]he things of the night”—Frederic knew—“cannot be explained in the day, because they do not then exist, and the night can be a dreadful time for lonely people once their loneliness has started. But with Catherine there was almost no difference in the night except that it was an even better time.” There follow the five sentences that Fitzgerald suggested might serve to conclude A Farewell to Arms: “If people bring so much courage to this world the world has to kill them to break them, so of course it kills them. The world breaks every one and afterward many are strong at the broken places. But those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure it will kill you too but there will be no special hurry.” Upon reading this soliloquy for the first time, Fitzgerald wrote in the margin of the typescript, “This is one of the most beautiful pages in all English literature.” In his letter to Hemingway, he called it “one of the best pages you've ever written.”

Hemingway had a famously difficult time deciding how to end his novel. Depending on how you count them up, he tried somewhere between thirty-twoand forty-one variant endings, including the one Fitzgerald proposed. What he finally settled upon was, of course, wonderful.

Early in his critique, after accusing Ernest of committing an uninteresting “sort of literary exercise” in the dialogue where Catherine discloses her fear of the rain, Scott added a parenthetical apology. “(Our poor old friendship probably won't survive this but there you are—better me than some nobody in the Literary Review that doesn't care about you and your future.)” Fitzgerald wanted to take the sting out of his comments: he was only doing this because he cared, because of their friendship. From Hemingway's point of view, however, that only made the criticism more painful. With a journeyman reviewer, he could work off his anger with a scornful wave of the hand—or at most with a satirical swipe of the pen, as he had the previous month in his “Valentine” poem for Lee Wilson Dodd, who had the effrontery to accuse him, in Men Without Women, of concentrating solely on “the short and simple annals of the hard-boiled.”

Fitzgerald's comments could not be so easily disposed of. He was an established and talented writer. He had been Hemingway's sponsor, and was to remain his friend, at least in the near term. And besides, Ernest had not entirely ignored the proposed changes. He cut the long passage of Frederic's musings, he considered Scott's idea for the ending, and he first x'ed out the scene with the opera singers and Moretti before restoring it to the text. So Ernest let the wound to his ego fester for a time before unleashing his powers of invention to discredit Scott's critical overtures.

Fitzgerald reintroduced the topic of revisions to Farewell in a June 1, 1934, letter responding to Hemingway's harsh words about Tender Is the Night. “[T]he old charming frankness” of Ernest's remarks cleared the air between them, Scott said, and he went on to discuss various literary problems, including how to end a novel. “I remember that your first draft [of Farewell]—or at least the first one I saw—gave a sort of old-fashioned Alger book summary of the future lives of the characters: “The priest became a priest under Fascism,' etc., and you may remember my suggestion to take a burst of eloquence from anywhere in the book that you could find it and tag off with that; you were against this idea because you felt that the true line of a work of fiction was to take a reader up to a high emotional pitch but then let him down or ease him off. You gave no aesthetic reason for this —nevertheless, you convinced me.” As a consequence, he made a “direct steal” from Hemingway and ended Tender with Dick Diver drifting off into obscurity.

This letter is noteworthy for its generosity of spirit and manifest unwillingness to offend. Fitzgerald tactfully forgets to remember, for instance, that he had proposed a specific passage for ending Farewell [“If people bring so muchcourage to this world…”], instead leaving such a choice to Hemingway's considered judgment. Even more tactfully he inverts the teacher-pupil status of their relationship. Now it is Scott who expresses his debt to Ernest for showing him how to end his novel, much as Ernest might have (if he could have) thanked Scott for fixing the beginning of Sun. Fitzgerald's letter also makes it clear that he and Hemingway talked about these issues in Paris, in June 1929.

One might think that Ernest's bruised ego could have healed in the interim between 1929 and 1934, or that Scott's ameliorative tone might have done the job. One would be wrong. Hemingway did not reply to Fitzgerald's June 1 letter, and instead began a campaign to discredit everything Scott had to say about A Farewell to Arms. “[Y]ou may remember,” Scott had written, but Ernest chose to misremember the revisions Fitzgerald proposed through a pattern of exaggerations, lies, and outright inventions—the weapons that writers of fiction keep ready at hand to guard their territory.

The first salvo came in a December 1934 letter to Maxwell Perkins. “I will show you some time [Scott's] suggestions to me on how to improve the typescript of A Farewell to Arms which included writing in a flash where the hero reads about the victory of the U.S. Marines.” Invention. “He also made many other suggestions none of which I used.” Falsehood. “Some were funny, some were sad, all were well meant.” Patronizing slur.

Forward to 1942, when Hemingway wrote his lawyer Maurice Speiser granting permission to Edmund Wilson to quote from any of the Fitzgerald's “non-libellous letters” about him in The Crack-Up, the 1945 collection of Fitzgerald essays, letters, and notes along with letters and appreciative essays and poems from others. Wilson had sent along a number of letters which referred to Hemingway, including the July 1936 one to John O'Hara where Fitzgerald carefully downplayed his contribution to The Sun Also Rises before going on to discuss the ending of A Farewell to Arms. Ernest was in doubt about how to end the book, Scott wrote, “and marketed around to half a dozen people for their advice.” Fitzgerald “worked like hell” on the assignment, but only evolved a philosophy “utterly contrary” to Hemingway's. Later Ernest convinced him that he was right and so he ended Tender Is the Night “on a fade away instead of a staccato.”

He had not “marketed around” to half a dozen people, Hemingway told Speiser. He had simply shown Fitzgerald the manuscript at his request, and subsequently been appalled by the “idiotic idea” for an ending he proposed: “Lieut. Henry to be sitting in a Cafe and pick up a paper and read that the U.S. Marines had just taken Belleau Wood!” Invention, elaborated upon. He “was obliged toreject this suggestion in forceful terms,” Ernest wrote, “and Scott was upset about it for a long time.” Probable falsehood.

Hemingway went on to disparage what he considered to be Fitzgerald's lack of artistic integrity, citing as evidence a conversation between the two writers during 1929, when they were at odds about Farewell. “He told me how he wrote a story to please himself and then changed it to sell it to the Saturday Evening Post. I told him if he kept that up he would make himself impotent as a writer and would finally kill himself.” Hemingway instructed his lawyer to send his letter along to Wilson, and in a postscript asserted his fondness for Fitzgerald and his inside knowledge of the “real causes of his crack-up, which cannot yet be published.”

As time wore on and the posthumous Fitzgerald revival got underway, Hemingway's comments on the critique of Farewell became progressively more demeaning. Forward to January 1951, Hemingway to Arthur Mizener following publication of his biography of Fitzgerald. “I have a letter in which [Scott] told me how to make A Farewell to Arms a successful book which included some fifty suggestions” exaggeration “including eliminating the officer shooting the sergeant” invention “and bringing in, actually and honest to God, the U.S. Marines (Lt. Henry reads of their success at Belleau Woods while in the Cafe when Catherine is dying) at the end.” Invention, further elaborated upon. “It is one of the worst damned documents I have ever read and I would give it to no one.” A good thing, for it would contradict what he was saying.

Forward to January 1953, Hemingway to Charles Poore, who was in the process of editing The Hemingway Reader for Scribner's. He did the final rewrite of Farewell in Paris, Hemingway wrote Poore, and he could be sure of that because he had Fitzgerald's long letter as evidence. “[H]e said I must not under any circumstances let Lt. Henry shoot the sergeant” invention, reiterated “and suggesting that after Catherine dies Frederic Henry should go to the cafe and pick up a paper and read that the Marines were holding at Chateau Thierry.” Invention, altered with respect to two details. “This, Scott said, would make the American public understand the book better. He also did not like the scene in the old Hotel Cavour in Milano “falsehood” and wanted changes to be made in many other places 'to make it more acceptable.'” False quotation. “Not one suggestion made sense or was useful.” Falsehood. “He never saw the [manuscript] until it was completed as published.” Partial truth. “…I had learned not to show them to him a long time before.” Declaration of independence, after the fact.

In his criticism of A Farewell to Arms, Fitzgerald warned Hemingway that the rough barracks language of the novel might well lead to censorship. “I thinkif you use the word cocksuckers here [during the retreat, in two places] the book will be suppressed & confiscated within two days of publication.” This was a problem Perkins immediately anticipated upon reading the manuscript in Key West, early in February. “book very fine but difficult in spots” he wired New York. Later, in a letter to Charles Scribner (who held strict views about what should or should not be printed), he expanded on the point. “It is Hemingway's principle both in life and literature never to flinch from facts, and it is in that sense only, that the book is difficult. It isn't at all erotic, although love is represented as having a very large physical element.” Perkins was playing the role of middleman here, trying to reassure his boss (Scribner) that the novel was publishable and to keep Hemingway from erupting in anger when he heard about the emendations that, Max knew, would have to be made.

The plot of the novel itself, involving a somewhat idealized love affair out of wedlock, was “salacious” enough to get A Farewell to Arms banned in Boston. More accurately, the second installment of the six-part serial version of the novel in Scribner's magazine was banned there by police chief Michael H. Crowley on June 20, 1929. The ruling banned distribution of the magazine by Boston bookstores and newsstands for the run of the serial over the next four months. It did not hurt overall circulation figures of the magazine, and undoubtedly stimulated sales of the book when it was published on September 27.

Still, the Boston censorship gave Perkins a certain amount of ammunition as he and Hemingway went to battle on the question of obscene language. The serial had substituted blank spaces for these words—separate instances of “fuck,” “shit,” and “balls” as well as “cocksuckers”—on the grounds that Scribner's magazine was widely read by young people, girls as well as boys. But Hemingway wanted the words restored for the novel: he was merely re-creating the way soldiers talked. Fitzgerald, who would never himself have written such language for publication, nonetheless secured and delivered to Hemingway a copy of Erich Maria Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front, a war novel then enjoying a phenomenal success in Germany and England, with an American edition about to emerge. Armed with the evidence, Ernest wrote Max that all of his offending words —or all but one, anyway —appeared in All Quiet. Remarque's soldiers talked dirty, just as he wanted his to. He hated “to kill the value of [his novel] by emasculating it.”

But Hemingway offered Perkins a way out of his dilemma. “If [any given word] cannot be printed without the book being suppressed all right.” After the Boston ban, Max was able to argue that suppression was a very real possibility.As Ernest wrote Scott, restoring him to the status of literary confidant and adviser, “Max sounded scared. If they get scared now and lay off the book I'll be out of luck.” He wished he'd asked for an advance, because “it is more difficult to lay off a book if they have money tied up in it already.” Perkins reassured Hemingway about an advance. He could have $5,000 or more, if he wanted it. At the same time, though, the Scribner's editor presented the company-man argument that an advance could be “very discouraging to an author (take Scott for example)” whose book sold well but who had no royalty coming because of a large advance. He did not add that most writers (including Scott for example) would be more than willing to deal with so rewarding a form of discouragement.

When he heard about the banning of Scribner 's magazine, Fitzgerald wrote Perkins that Hemingway “sounded worried, but I don't see why. To hell with the toughs of Boston.” By the end of July, however, Ernest capitulated to Perkins's warnings about suppression. “I understand,” he wrote Perkins, “…about the words you cannot print—if you cannot print them—and I never expected you could print the one word (C—S) that you cannot and that lets me out.” Fitzgerald did not get the message that the battle was lost. In an August 23 letter to Hemingway, he took credit for sending Perkins “one of those don't-lose-your-head notes.” He'd always believed, Scott added, that if the dispute about dirty words came to a crisis stage Max would “threaten to resign and force [Scribner's] hand.”

At their summertime base in Cannes, the Fitzgeralds spent a miserable few months. Zelda went into Nice daily to work on her dancing, while Scott partied with whatever companions he could find. “It's been gay here,” Scott wrote Ernest, “but we are, thank God, desperately unpopular and not invited anywhere.” According to Zelda, he managed to alienate most of his old friends on the Riviera. “You disgraced yourself at the Barrys' party, on the yacht at Monte Carlo, at the Casino with Gerald and Dotty [Parker],” she wrote. Scott admitted as much, privately, in his Ledger. “Being drunk and snubbed.”

On the bright side, his unpopularity released time for work, and Fitzgerald did turn an important corner during the months on the Riviera, giving up the matricide theme for his novel and turning instead to the story of a movie director and his wife (Lew and Nicole Kelly) who encounter a stunning young actress named Rosemary on a shipboard crossing to Europe. Fitzgerald was only beginning to reshape the material that would form Tender Is the Night. As usual, he exaggerated his progress. “I've been working like hell, better than for four years,” he told Hemingway. He was confident that he could finish his novel “before the ail-American [football] teams” were picked.

“I can't tell you how glad I am you are getting the book done,” Ernest wrote back. He had his doubts, though, for Scott might not be finishing the novel at all “but only putting [him] on the list of friends to receive the more glowing reports.” Then Hemingway revealed directly to Fitzgerald what he had been telling Perkins for some time: that Scott had been “constipated” by the reviews of Gatsby and especially by Gilbert Seldes's praise. That made him self-consciously decide he had to write a masterpiece, instead of “going on the system that if this one when it's done isn't a Masterpiece maybe the next one will be.” He knew there were “other complications,” Ernest said, without mentioning Zelda or alcohol. Still, what Scott ought to do was to save “the juice” he wasted on Saturday Evening Post stories and use it for his novel.

Actually, Hemingway himself wasn't being particularly productive either. By September it had been a year since he finished the first draft of A Farewell to Arms, and not much had been written since. As tended to happen when he was not working, he was beset with physical ailments real and imaginary. Hemingway was in a sour mood waiting for his book to come out, feeling lousy and worried about its reception from the critics and the public and the censors. With his uncanny knack for bad timing, Fitzgerald chose that particular time to place the already fraying ties of their friendship under tremendous pressure.

The troubles began with Scott's unwanted criticism of Farewell and his sloppy timekeeping in Ernest's sparring match with Morley Callaghan. During the summer on the Riviera, Fitzgerald managed to complicate his friend's living arrangements in Paris through the Vallombrosa affair. Back in Paris during the fall, he embarked on a series of worrisome interventions in connection with Hemingway's novel. In December, the soirée at Gertrude Stein's brought the issue of rivalry between them into the open.

Most of these vexations derived from Scott's eagerness to be involved in Ernest's life and career. When the two men first met, those involvements worked to Hemingway's benefit. By 1929 they no longer did. To Ernest, Scott's intrusions into his affairs looked like nothing so much as meddling.

To begin with, Fitzgerald could not keep his mouth shut. Ernest and Pauline then planned to maintain a base in Paris—a decision that was countermanded by their return to Key West in January 1930—and with that in mind paid $3,000 to sublet the rue de Férou apartment. After the two men renewed contact in May, Ernest told Scott in considerable heat about the day he was working at home when a group of prospective renters arrived to look it over. He did not want to lose the apartment, and he did not like being interrupted at work.

The Hemingways leased the flat through the good offices of Ruth Goldbeck Vallombrosa, an attractive member of the international set. Ruth happened to be on the Riviera that summer, where Fitzgerald happened to run into her and could not resist telling her about Hemingway's anger. As Scott construed the conversation in his letter to Ernest, it is clear that he viewed himself as having done his friend yet another service.

Now—Ruth Goldbeck Vallombrosa [actually, Scott spelled it Voallammbbrrosssa, probably for comic effect] not only had no intention of throwing you out in any case, but has even promised on her own initiative to speak to whoever it is (she knows her) has the place. She is a fine woman, I think; one of the most attractive in evidence at this moment, and not deserving of that nervous bitterness.

Hemingway replied that although Fitzgerald obviously remembered his “nervous bitterness”—his blowing up about people coming in to look at the apartment—he seemed to have “damned well” forgotten that Ernest came around to see him about it the next day and to explain that under no circumstances did he want Ruth Goldbeck Vallombrosa [Ernest spelled it Vallambrosa] to know how angry he had been. “She did not know I was sore and the only way she would ever find out would be through you. You said you understood perfectly and for me not to worry you would never mention it to her.”

Fitzgerald tried to calm the waters. “[Incidentally,” he wrote back, “I thought you wanted a word said to Ruth G. if it came about naturally—I merely remarked that you'd be disappointed if you lost your apartment—never a word that you'd been exasperated.” Hemingway could hardly have been reassured on that point, however, for Fitzgerald went on in a highly explicit manner to describe his pattern of behavior when drinking. He tended to dissolve in tears about 11 p.m., and to tell anyone who would listen that he hadn't a friend in the world. Not many would listen for long, Scott admitted, for he would go on and on. He'd never been able to hold his tongue: “when drunk I make them all pay and pay and pay.”

In the same confessional spirit, Fitzgerald discussed the long dry period on his novel. He thought Ernest's analysis about overpraise having dammed the flow was “too kind in that it leaves out the dissipation.” What really worried him was the remarkable output of 1919-1924: three novels including Gatsby, about fifty stories, a play, and numerous articles. That spurt, he feared, “might have taken all [he] had to say too early,” especially considering that he and Zelda werethen “living at top speed in the gayest worlds [they] could find.” He closed with a self-deprecatory bulletin on the financial front. “[T]he Post now pays the old whore $4000 a screw. But now it's because she's mastered the 40 positions—in her youth one was enough.” This time, Fitzgerald did not inflate his price.

Hemingway heard and responded to the cry for help in this letter. Exasperating as Fitzgerald could sometimes be, Hemingway still felt a real warmth toward him. So his letter of September 13 corrected Scott's crying-drunk statement that he had no friends. He should say instead that he had “no friends but Ernest the stinking serial king.” Nor should Scott feel bad about his lack of literary production. Everybody lost the early bloom, he assured Fitzgerald. “You lose everything that is fresh and everything that is easy and it always seems as though you could never write” again, but that wasn't true, for you had “more metier and you know more” and when you got flashes of the old juice you could do more with them.

Above all Hemingway encouraged Fitzgerald not to give up. Appropriating to himself the position of mentor, Ernest insisted that there was only one thing to do with a novel and that was to “go straight on through to the end of the damn thing.” If only Scott's economic existence depended on the novel and not on short stories! As always when sentiment threatened to intrude, Hemingway couched his message of support in invective. “Oh Hell. You still have more stuff than anyone and you care more about it and for Christ sake just keep on and go through with it now and don't please write anything else until it's finished. It will be damned good.” The stories weren't whoring at all, just bad judgment. Scott could make enough to live on writing novels.

The Bout with Morley Callaghan

Morley Callaghan, a young Canadian writer, came to Paris in the spring of 1929 and unwittingly drove a wedge between Fitzgerald and Hemingway, the two American writers he was most eager to see and talk to. The trouble came to a climax in a sparring contest with Hemingway late in June, but it had repercussions that lasted until the end of the year and beyond.

Hemingway met Callaghan in 1923 when both were working for the Toronto Star Weekly. After a couple of years as roving correspondent in Europe, Hemingway cut a rather glamorous figure in the Star newsroom. People wereconverting his exploits into the stuff of legend. But what most impressed Callaghan was Hemingway's devotion to the craft of writing. “A writer,” he said, “is like a priest,” for both professions required the same kind of discipline and commitment. Three years younger than Ernest and an aspiring writer of fiction himself, Morley listened with fascination.

Five years later, when Scribner's published Callaghan's short-story collection, Native Argosy, Fitzgerald and Hemingway both signaled their approval. “I think he really has it—personality, or whatever it is,” Fitzgerald wrote Perkins. He doubted, though, that Morley was “as distinctive a figure as Ernest.” The following year, Callaghan came to Paris, and found himself in the middle of the intensely strained relationship between Scott and Ernest. He even wrote a book about it—That Summer in Paris—that was published in 1963. One of the few full-scale reports of the Fitzgerald-Hemingway friendship, this memoir is not entirely objective in its rendering of what happened in Paris, summer of 1929. Many years had elapsed to rub away the memories, and as one might expect, Callaghan made sure that he did not come off badly.

When he arrived in Paris, Callaghan had it in mind to renew his acquaintance with Hemingway and to look up Fitzgerald. He admired both writers, and Max Perkins encouraged him to make contact with them. From the start Perkins had been bewitched by Hemingway's tales of bullfights and boxing. He told Callaghan as if it were gospel a yarn about Ernest knocking out the middleweight champion of France. Callaghan knew that was nonsense, that in boxing as in any other sport, the professional would invariably defeat the amateur. In Paris, he was to find out more about Hemingway—and Fitzgerald—in the ring.

One of Callaghan's short stories used a boxing milieu. Hemingway, whose “Fifty Grand” had established his claim as an expert on the sport, decided to find out if Callaghan knew what he was writing about. When Morley and his wife Loretto called on Ernest and Pauline in Paris, Ernest quizzed him about his experience. Yes, he had boxed quite a bit, Morley said. In fact, he was very fast with his hands. Oral assurances were not enough for Hemingway. He insisted that they strap on boxing gloves and maneuver gingerly around the furniture in the rue de Férou apartment. After a while, Ernest was satisfied. “I only wanted to see if you had done any boxing,” he said with a grin, ignoring the fact that he had failed to take Morley's word for it. The two men made a date to box the next afternoon at the American Club nearby, as they did on eight or nine other occasions that spring and summer.

As a fighter, Callaghan discovered, Hemingway “was a big rough toughclumsy unscientific man”—big enough and strong enough to clobber Morley in a back-alley brawl. With gloves on and given room to move around, Callaghan was able to hold his own. In boxing together, Ernest usually tried to nail Morley with a solid left hook, while Morley's technique was to slip those punches and deliver jabs with his quick left hand. It was a fair enough match. Hemingway had the power, Callaghan the speed. Often Morley would come home with welts on his arms and shoulders, badges that signified he had avoided taking Ernest's most damaging blows to the head. On one occasion, when he bloodied Ernest's lip with his jabs, Hemingway sucked in the blood and spat it at Callaghan. It was a terrible insult, Morley knew, but Ernest broke the tension by saying solemnly, “That's what the bullfighters do when they're wounded.” Then they showered and went off to the Falstaff, where they had a beer or two with proprietor James Charters, himself a former prizefighter.

Perkins told Callaghan that he did not need to stand on formality with Fitzgerald. Just drop in on Scott, he advised; he'll be glad to see you. That's what Callaghan did, and the initial results were not auspicious. As Morley recalled the meeting, he and Loretto stopped by the Fitzgeralds' apartment about nine-thirty one evening just as a taxicab deposited Scott and Zelda at their door. The Callaghans introduced themselves, and were invited inside, where Fitzgerald— much as he had with Glenway Wescott and Michael Arlen—invited a fellow novelist to join him in admiration of Ernest Hemingway. Scott read aloud the passage from A Farewell to Arms that he had proposed as an ending, the burst of rhetoric about how the “world” was sure to kill the very good and the very gentle and the very brave. “Isn't that beautiful?” he asked. Well, yes, of course it was, Morley said, but wasn't it also “too deliberate,” something of a set piece?

Fitzgerald took offense and began bombarding Callaghan with sarcastic questions. If that passage didn't impress Morley, what would impress him? Would Morley be impressed if Scott stood on his head? He tried to do so, lost his balance, and sprawled flat on his face. On the way home Callaghan decided Fitzgerald must have been drunk. Loretto wasn't so sure she liked the literary life. Her husband had encountered in Paris the two American writers whose work he most respected. One of them had spit at him, and the other one stood on his head.

The next day, Morley wrote a letter to Scott. As he re-created it in That Summer in Paris, this note consisted of an apology about coming by without making an appointment ahead of time. He'd only done so because Max Perkins assured him it would be all right. If he and his wife had upset Scott and Zelda in any way, or kept them up, they were sorry.

Callaghan somewhat rearranged the facts in his memoir. The actual letter, which Fitzgerald preserved, was that of a bitter man whose ego has been sorely bruised. It was written the morning after Morley had dropped by the Fitzgeralds' unannounced, for the second time. On the first occasion, Scott and Zelda had been tired, having just returned home from the theater, but Morley nonetheless left the manuscript of his as yet unpublished novel, It's Never Over, for Fitzgerald to read. He was understandably eager to hear what Fitzgerald thought of the book, and had gone to their apartment the previous night to find out.

“Your frank opinion of the book is honestly appreciated,” Morley wrote. “It was what I wanted. If I had caught you at any other time I would have been the poorer for it. Please don't think I resent the way you told me the novel was rotten. [Italics added.] It would have been much easier for you to have said that it was a nice piece of work, and so I am grateful to you.” Elsewhere in the letter, however, the injured Callaghan could not maintain this high-minded tone. He summarily refused an invitation to lunch with the Fitzgeralds. “It was very kind of you to ask us, but, if I remember correctly, I made it almost impossible for you to do otherwise.” Perhaps they might see each other “sometime” at one of the cafés, he commented, before concluding with a final angry sentence. “And I am sure you'll understand why we can not have lunch together on Wednesday.”

This letter provoked an extraordinary reaction from Fitzgerald. According to Callaghan, he sent three separate pneumatiques in an attempt to make amends, and he and Zelda turned up at Morley and Loretto's apartment with the same goal in mind. “Never in my life,” Morley recalled, “had anyone come to me so openly anxious to rectify a situation.” It was a pattern with Fitzgerald: he did outrageous things to alienate people, and then went to great lengths to repair the damage. He could not stand to have others think badly of him.

In any case, the Callaghans and Fitzgeralds continued to see each other, and Morley continued to box with Ernest. Gradually it became clear that he was caught in the middle of the estrangement between Fitzgerald and Hemingway about the apartment. Scott and Zelda had only recently arrived in Paris, and had not yet made connections with the Hemingways. Whenever Morley saw Scott, he was bombarded with questions about Ernest. Had the Callaghans seen the Hemingways? Oh, really, and how often? Why didn't Morley arrange a get-together for the three couples? Ernest failed to respond to such overtures when Morley advanced them. Furthermore, he instructed Callaghan not to reveal his address. He told Morley, as he had written Perkins, that he was afraid Scott would cause a drunken disturbance and get them kicked out of the place. Thereseemed to be more to it than that, Callaghan thought, “some other hidden resentment.” Naturally, he felt awkward about his role as middleman. Scott and Ernest were supposed to be great friends, and here he was in the anomalous position of trying to bring them together. Fitzgerald was particularly eager to see Ernest and Morley box. On the day he finally did, it turned out disastrously.

Callaghan and Hemingway wrote differing interpretations of what happened that June afternoon. These agreed only on the basic fact that Fitzgerald, asked to serve as timekeeper, let a round go too long and Hemingway fell to the canvas. In Callaghan's account, Scott and Ernest showed up at his door together in the best of humor but entirely sober, with Hemingway carrying the gloves. At the American Club, Scott listened attentively to his instructions. Ernest and Morley were fighting three-minute rounds, with one minute of rest in between. He was to call “time” at the end and beginning of each round. But Fitzgerald was caught up in the drama of the occasion, and—Morley thought—shocked to see Ernest's mouth bloodied by one of his jabs. Consequently he forgot to consult his watch, and as the round wore on, Callaghan stepped inside of one of Hemingway's roundhouse swings, caught Ernest flush on the jaw, and knocked him down, “sprawled out on his back.”

Only then did an alarmed Fitzgerald cry out, “Oh, my God! I let the round go four minutes.” Hemingway, who was not badly hurt physically, would have none of it. “If you want to see me getting the shit knocked out of me,” he savagely told Scott, “just say so. Only don't say you made a mistake.” As Callaghan recalled, a number of thoughts raced through his head at this outburst. Was the animosity in Scott or in Ernest? Did Ernest resent Scott for helping his career? Did Scott resent Ernest in some way? What he could see for sure was that Fitzgerald was every bit as distraught as Hemingway was angry. For weeks Scott had wanted to see them box and when he did, it brought on this crisis.

Before the afternoon was over, Fitzgerald managed to compound his error. Hemingway and Callaghan resumed their boxing after a brief intermission, and this time Scott was meticulous about his timekeeping. When Callaghan half tripped on the edge of a wrestling mat and went down on one knee, Fitzgerald called out “One knockdown to Ernest, one to Morley.” The remark, obviously meant to mollify Hemingway, only made things worse. “[I]f I had been Ernest,” Morley wrote, “I think I would have snarled at [Scott], no matter how good his intentions were.”

Hemingway sent his version of that bout to Max Perkins in August, during his summer sojourn in Spain. “You would not believe it to look at him,” he wrote of Callaghan, who was overweight and something of a dandy in his dress, “but he is a very good boxer.” On the day in question, Ernest said, he had an extensive lunch with Scott and John Peale Bishop at Prunier's, lobster thermidor and “several bottles of white burgundy,” followed by a couple of whiskeys. He could hardly see Morley when they started boxing, but he thought he could go hard for a minute at a time, and they agreed on one-minute rounds with two minutes of rest, Scott keeping time. Fitzgerald let the first round go three minutes and forty-five seconds—“so interested to see if I was going to hit the floor!” That did not happen, for although Morley was fast and really knew how to box, he could not hit hard. Ernest, terribly tired, did slip and fall down, pulling a tendon in his left shoulder. Later they resumed boxing, and he managed to sweat the alcohol out of his system. (In telling the story to Arthur Mizener in 1951, Ernest expanded on Scott's incompetence. As timekeeper, he asserted, Fitzgerald had let the round “go thirteen minutes!”)

That might have been the end of the affair, were it not for Hemingway's developing celebrity. In November, a third version of the match at the American Club made its way into the daily newspapers. This particular account, which originated in the Denver Post and traveled east to Isabel Patterson's gossipy literary column in the New York Herald-Tribune, put Ernest in the worst possible light. He had been sitting at the Dôme in Paris, telling one and all that Callaghan knew nothing about boxing. Hearing about this, Morley challenged him to a bout and before “a considerable audience” knocked him cold in a matter of seconds. The unidentified “amateur timekeeper” was so flustered that he forgot to count Hemingway out, and a critic in the audience had to do so.

As soon as Callaghan—now back in Toronto—read this story, he sent a correction to Patterson. He had boxed with Hemingway the previous summer, but they'd never had an audience and he had never knocked Ernest out. Once, it was true, they'd had a timekeeper, and if there “was any kind of a remarkable performance that afternoon the timekeeper deserved the applause.” Before his letter of correction was printed, Callaghan got a cable that infuriated him: “HAVE SEEN STORY IN HERALD TRIBUNE. ERNEST AND I AWAIT YOUR CORRECTION. SCOTT FITZGERALD.” And the cable came collect! He immediately posted an angry letter to Fitzgerald in Paris. There was no need for him to have rushed in to defend Hemingway. Only a son of a bitch would send such a cable without waiting to see what Morley would do. He assumed that Scott was “drunk as usual when he sent it.” Callaghan also wrote Perkins about the cable, and Max set about trying to calm down his authors.

There ensued an outpouring of correspondence between these four principals. December 12, 1929, Hemingway to Fitzgerald, obviously written after the two men had discussed the infamous boxing match and after Scott had sent the cable—at Hemingway's instigation—to Callaghan. “I know you are the soul of honor,” Ernest assured Scott. “If you remember I made no cracks about your time keeping until after you had told me over my objections for about the fourth time that you were going to deliberately quarrel with me.” Sore as he was about the whole thing, he had never accused Scott of time juggling, only asked if he “had let the round go on to see what would happen.” That sort of thing often occurred with amateur timekeepers. At the time, he reminded Fitzgerald, he placed no importance on the incident, instead praising Morley for knocking him around. It was only when he read Callaghan's “lying boast” that he became angry.

Hemingway, obviously, felt that the knockout story had originated with Callaghan. From the context of his letter, it is apparent that Fitzgerald was deeply disturbed by the whole incident, and by its unfortunate aftermath. After recounting a yarn about dirty tricks in the prize ring, Ernest returned to his reassurances. “It was only when you were telling me, against all my arguments and telling you how fond I am of you, that you were going to break etc. and that you had a need to smash me as a man etc. that I relapsed into the damn old animal suspicion. But… I believe you implicitly.”

December 17, 1929, Perkins to Fitzgerald, enclosing the letter he got from Callaghan and the note he sent to the Herald-Tribune, along with news of how the rumor got started through a reporter named Caroline Bancroft who worked for the Denver paper.

December 27, 1929, Perkins to Hemingway, telling about a lunch during which Callaghan told Max he didn't think he could last through the “heart-breaking round” when Scott got distracted and forgot to call time.

January 1, 1930, Fitzgerald to Callaghan, a “dignified, half-formal” letter apologizing for his “stupid and hasty” telegram and assuring Morley he never suspected him of starting the rumor.

January 4, 1930, Hemingway to Callaghan, revealing that Scott had sent the cable “at [Ernest's] request and against his own good judgment.” The wire was entirely his fault, Hemingway insisted, adding belligerently that if Morley wanted to transfer to him the epithets he applied to Scott he expected to be in the States in a few weeks and would place himself “at your disposal any place where there is no publicity attached.”

January 10, 1930, Hemingway to Perkins, thanking him for his letter of December 27 and saying that Pauline “mailed by mistake a letter [he'd] written Callaghan [the one quoted immediately above] and then, on Scott's more or lessinsistence decided better not send.” The letter to Callaghan was sent in care of Scribner's, and if it was still there Max should hold on to it for him. Ernest also sent a cable asking Perkins not to relay his letter to Callaghan, but to no avail— it had already been forwarded.

Mid-January 1930, Callaghan to Hemingway, in receipt of the January 4 invitation to duke things out, and with a show of belligerence himself, pointing out that he could not in good conscience transfer the epithets he'd used to Scott. Since Ernest had compelled Scott to send the cable, Morley would have to come up “with a whole fresh set of epithets” for him.

January 21, 1930, Fitzgerald to Perkins, thanking him for the documents “in the Callaghan case. I'd rather not discuss it except to say that I don't like him and that I wrote him a formal letter of apology. I never thought he started the rumor and never said nor implied such a thing to Ernest.”

February 21, 1930, Hemingway to Callaghan, admitting he'd over-reacted and that he'd not intented to mail his January 4 letter yet still insisting that he could knock out Morley in five two-minute rounds if they used small gloves.

Late February, 1930, Callaghan to Hemingway, saying he did not think Ernest could knock him out but it was all right with him if Ernest wanted to think so, and meanwhile why not disarm?

The clear loser in the boxing match between Callaghan and Hemingway was Fitzgerald. He angered Hemingway by letting the round go on too long and later, by not letting the whole sorry incident fade away. He may have hoped to redeem himself in Ernest's eyes by sending the cable to Callaghan demanding a correction, but only succeeded in arousing Morley's ire and further humiliating himself.

Looking back on his acquaintance with the two men in Paris, Callaghan essayed a psychological comparison between them. Both Scott and Ernest were “extraordinarily attractive men.” One difference was that Fitzgerald had a knack for making himself look worse than he was, while no matter what Hemingway did, he managed to emerge in a favorable light. At the end of his memoir, Callaghan illustrated his own point. If there is a villain in That Summer in Paris, it is surely Ernest Hemingway. Yet Callaghan maintained in closing that the Hemingway he knew in Paris, the author of A Farewell to Arms, was “perhaps the nicest man” he ever met—“reticent… often strangely ingrown and hidden with something sweet and gentle about him.” His tragic flaw, Callaghan speculated, may have been his capacity “for moving others to make legends out of his life,” a fault as nearly debilitating “as Scott's instinct for courting humiliation from his inferiors.”

Roiling the Waters

Throughout the fall months of 1929, when both of them returned to Paris after summers elsewhere on the Continent, Scott continued to advise Ernest and to attempt to guide his career. But his advice was no longer wanted, and no longer particularly helpful. At best his suggestions created tension in their relationship. At worst they threatened to break it off entirely.

With A Farewell to Arms a prospective best-seller, Ernest was again in demand among American agents and publishers. Harold Ober pressed his interest in representing Hemingway, and assumed that Fitzgerald could help bring Ernest into the fold. Early in the year, Ober wrote Fitzgerald about a volume of the best modern short stories the Modern Library planned to publish. Ober thought Fitzgerald ought to be represented in the book, which was to include work by Sherwood Anderson, Joseph Conrad, E.M. Forster, D.H. Lawrence, Katharine Mansfield, and Somerset Maugham, but Scribner's balked at the proposal. Couldn't Scott change their minds? And couldn't he deliver as well a story each from his friends Ernest Hemingway and Ring Lardner? Fitzgerald promised to talk to Max Perkins about it; he felt sure that Bennett Cerf at the Modern Library could count on something from him. Great Modern Short Stories, published in 1930, included Fitzgerald's “At Your Age” and Hemingway's “The Three-Day Blow,” neither of which ranked with the best of their work, and nothing from Lardner.

In September, Ober severed his connections with the Paul Reynolds agency, and struck out on his own. Ober had been Fitzgerald's agent from the start, and telegraphed Scott to come along with him. “YOU OWE REYNOLDS NOTHING. I WILL GLADLY MAKE YOU ADVANCES WHEN NEEDED STOP TO AVOID INTERRUPTION WORK PLEASE CABLE ME AUTHORIZATION TO CONTINUE.” Then Ober immediately went on to request that Fitzgerald “PERSUADE HEMINGWAY TO SEND STUFF THROUGH YOU TO ME.”

Fitzgerald stuck with Ober, a decision made easier by a letter from Reynolds saying that since Ober had handled Scott's work all along it was only fair that he should go on handling it. But Reynolds did not give up so easily on Hemingway, who had resisted signing up with any agent. Without telling Ober, who “they knew perfectly well… had been discussing Hemingway['s]” situation with Fitzgerald, Reynolds and his son tried to negotiate sale of a Hemingway story to Collier's—and so to earn status as his agents. An angry Ober asked Scott to intervene with Ernest on his behalf andagainst the machinations of the Reynoldses. “If there is any way you can steer [Hemingway] my way,” he wrote Fitzgerald October 8, “I should appreciate it. I know he thinks a great deal of your advice.”

Fitzgerald forwarded this letter to Hemingway, along with a marginal note declaring that he would stay out of the battle over Ernest's work in future, now that he didn't “need any help.” In further communication with Ober, he scolded his agent for not moving more quickly to sign up Hemingway. It had been “foolish to let him slide so long as he was so obviously a comer.” One way to get Ernest's attention, Fitzgerald proposed in mid-November, was to negotiate a motion picture sale for $20,000 or more. But he cautioned Ober to keep his name out of any communications with Hemingway: “[Y]ou see my relations with him are entirely friendly & not business & he'd merely lose confidence in me if he felt he was being hemmed in by any coalition.”

Though Fitzgerald more or less kept his distance on the agent front, he remained actively—and at times annoyingly—involved in Hemingway's professional relations with Scribner's, particularly with respect to A Farewell to Arms. Scott managed to dishearten Ernest about sales of the novel, for example, despite its obvious success in the marketplace. He also incited Hemingway to seek higher royalties from the book than he had contracted for, and even to become involved in its advertising.

A week after publication of A Farewell to Arms on September 27, Hemingway wrote a discouraged letter to Perkins. His mood was largely attributable to authorial postpartum blues, with Fitzgerald helping the melancholy along. He'd always figured, Ernest wrote Max, that if you wrote good books they would sell a certain amount and someday you could live on what they brought in. But Scott told him that was “all bunk— [t]hat a book only sells for a short time and that afterwards it never sells and that it doesn't pay the publishers even to bother with it.” (Time was to prove how wrong Fitzgerald was about this, both as regards Hemingway's books and his own.) Writing and publishing books was “just a damned racket like all the rest of it,” Ernest said. The only thing he'd gotten out of Farewell was disappointment. At least he had earned some money for the magazine serial. Now the book itself had to make money, so that he could support the family his father had so abruptly left behind.

Fitzgerald predicted the novel would sell more than 50,000 copies, and it did considerably better than that. On October 15, after an anxious Hemingway wrote and wired him for a report, Perkins cabled that the first printing of 30,000 copies was sold out and two more printings of 10,000 each had been run.Prospects looked good, or would have done so except for the stock market crash. The day after Black Tuesday, Perkins wrote Fitzgerald that sales of Farewell had reached 36,000 and that no book “could have been better received” by the critics and the public. (Actually, several of the early reviews were negative.) The “only obstacle” he could see to a really big sale was that the collapse of the market could have “a very bad effect on all retail business, including that of books.” For the moment Scott refrained from passing on this alarming bit of news to Ernest, but he did urge him to seek a 20 percent royalty once sales went beyond a certain figure. He'd had that arrangement with Scribner's for his books, Fitzgerald pointed out.

The issue emerged in Perkins's November 12 letter to Hemingway. The editor began with a report that Farewell had been leading the best-seller lists ever since publication, except for one week when it was edged out by All Quiet on the Western Front. Sales had reached 45,000, and a total of 70,000 copies had been printed, with paper on hand for another 20,000. But all that success had made Hemingway an extremely desirable commodity, and rumors were rampant in the publishing industry that he was dissatisfied with Scribner's. Offers might have been coming Ernest's way, and Max acknowledged that Scribner's was hardly in a position to ask him to refuse them unless they were willing to make equal offers themselves. If Ernest wanted $25,000 right now, for example, they would gladly advance it to him. Finally, Perkins got to the royalty question.

Things were not the same as they were when they'd first published Fitzgerald, Perkins asserted. Costs were higher, discounts were deeper, and most publishers felt that a 20 percent royalty was too high, that 15 percent was about all a book could bear if it was to be heavily advertised. Still, if Hemingway demanded a 20 percent royalty, even from the first copy sold, they would probably pay it “and face a loss, if necessary.” Perkins suggested an alternative that would be fair both to author and publisher. When the six months' royalty report was due, they would be able to calculate the profit that Farewell had generated, and could then revise the terms of the contract retroactively.

Hemingway replied that he had no intention of trying to “bid up” his price “It was only when Scott asked me what my arrangements were for a big sale that I mentioned it to you.” He was still upset about the barracks language that had been cut out of the novel, feeling that he'd lost his integrity in permitting such excisions. He'd had no interest in the book since, other than as something to “sell by God and fix up my mother and the rest of them.” He was setting up a $50,000 trust fund for his mother. An outside source—probably Pauline's uncle Gus—had promised $30,000 for that purpose, and he'd need $20,000 from Scribner's against royalties after the first of the year.

Perkins did not wait six months, or even until the end of 1929, to amend the royalty rate in Hemingway's contract. Sales continued to soar, and publishers continued to stir up harmful rumors about Ernest's supposed discontent with Scribner's. On December 10, Perkins wrote Hemingway that the contract had been revised. In talking it over with Charles Scribner, Max suggested 17 1/2 percent after 25,000 copies and 20 percent after 45,000, but Mr. Scribner said, “No, 20% after 25,000” and that was to be the rate. If Ernest had any objections, he had only to let Max know. As of that date, about 60,000 copies had been sold.

Fitzgerald was reluctant to relinquish his role as savvy inside adviser to Hemingway. In mid-November, while Ernest was on a trip to Berlin to see his German publisher, Scott came by the rue de Férou apartment and confronted Pauline with Max Perkins's warning about the possible downturn in sales of Farewell owing to the stock market crash. He was obviously alarmed, Pauline became alarmed, and when Ernest got back to Paris he joined in the general alarm. But Fitzgerald also suggested a solution: a new advertising campaign to keep sales humming along. In two letters to Perkins—the first of them unsent— Ernest presented that idea.

If sales started to fall off, he wrote, Scott's notion was that Scribner's “should start advertising the book as a love story—which it certainly is as well as a war story.” There were other war books on the shelves—Remarque's All Quiet, in particular—that might crowd Farewell, so the thing to do was to emphasize how it differed. In the letter he decided not to send, Hemingway submitted three separate samples of copy Perkins could use to “hammer” away on his novel as a love story. One of these read as follows:

There's more than

War in

A Farewell to Arms

It is

The Great Modern Love Story

It made him sick to write such stuff, Hemingway admitted, but he pleaded necessity. “You sell the intelligent ones first. Then you have to hammer hammer hammer on something to sell the rest.” In the letter he actually sent Perkins, written after a two-day cooling off period, Hemingway advanced Fitzgerald's great modern love story angle but refrained from submitting sample copy for the advertising department. Scott may well have over-reacted, Ernest speculated, as in fact he had. Farewell continued to sell at a splendid pace.

Three years earlier Fitzgerald had functioned admirably behind the scenes in guiding Hemingway to Scribner's. Now he only succeeded in engendering anxiety in Ernest and stirring up trouble for Max. In writing to Perkins, Hemingway articulated his irritation at his friend's behavior. He apologized for bothering Max “about the sale stopping,” but Scott had come by in some alarm and since he knew “so much more about the financial side of writing” Ernest had become disturbed also. “Am damned fond of Scott and would do anything for him but he's been a little trying lately.”

Une Soirée Chez Mademoiselle Stein

Hovering in the background—always there and nearly always mute—was the demon of literary rivalry. It emerged one early December evening at Gertrude Stein's party. Hemingway's admiration for Stein had cooled considerably over the years. By 1928, he was telling Fitzgerald that Stein had not known a moment's unhappiness with her work since she took up “not making sense.” And in “My Own Life,” a satirical 1927 New Yorker piece, he described how he had been banned from Stein's gatherings when he graduated from being her pupil to a writer in his own right. The maid had beaten him about the head with a bicycle pump to keep him away, he wrote, and when he persisted Stein nailed the door shut and posted an attack dog. Hemingway was eager to minimize the importance of Stein's influence on his work. Making fun of her was an amiable way to accomplish that.

It must have been particularly galling, then, when Fanny Butcher in her Chicago Tribune review of A Farewell to Arms—the review that would have been read by his relatives and friends in and around Oak Park—hailed him as a genius on the one hand and on the other described him as “the direct blossoming of Gertrude Stein's art.” He found out directly what Stein thought of his novel during her party in December.

She asked Hemingway to bring Fitzgerald and Allen Tate along to the Wednesday evening gathering. “She claims you are the one of all us guys with the most talent, etc. and wants to see you again,” he wrote Scott. At the appointedtime, Ernest showed up with a party of nine: the Fitzgeralds, the Hemingways, the Tates (Caroline Gordon), John Peale Bishop and his wife Margaret, and Ford Madox Ford. Stein used the occasion to present a lecture on American literature, tracing the path of greatness from R.W. Emerson through Henry James to the present site of genius, her own flat on the rue de Fleurus.

Afterwards, she told Ernest that she thought Farewell was fine when he was inventing, and not so good when he started remembering. When Fitzgerald joined the conversation, Stein went on to remark that his “flame” and Ernest's were very different. According to The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, the concept of a writer's flame came from Hemingway himself. Supposedly, he said that “I turn my flame which is a small one down and down and then suddenly there is a big explosion. If there were nothing but explosions my work would be so exciting nobody could bear it.” On this particular evening, it seemed clear to Hemingway that Stein preferred Fitzgerald's flame to his. Scott refused to see the point, and on their walk home badgered Hemingway relentlessly about her remark.

The next morning, very much as usual, a note of apology arrived from Fitzgerald, and Hemingway took advantage of his hangover to answer at once. He hadn't been annoyed at anything Scott said the night before, only by his refusal “to accept the sincere compliment” Stein was paying him. Instead, Scott had insisted on trying to convert her praise “into a slighting remark.” He also seemed determined to interpret her cryptic comment about their differing flames into a preference for Hemingway, when Ernest felt sure that she meant Scott “had a hell of a roaring furnace of talent” and he had a small one. Why Fitzgerald chose to interpret Stein's observation in this way was a question that invited still other questions. Was he really so modest about his own abilities that he could not believe her admiration was sincere? Or was he fearful that by accepting her praise at face value he would damage Hemingway's pride and so earn his enmity?

The hypothetical “flames” stuff was “pure horseshit” anyway, Ernest maintained in his letter. As writers he and Scott started along “entirely separate lines,” and the only thing they had in common was the desire to write well. Between serious writers there could be no sensible talk about superiority. They were all in the same boat. Competition “within that boat—which is headed toward death— [was] as silly as deck sports are.” This extremely sensible and dispassionate discourse came, as Fitzgerald knew, from one of the most competitive persons on the face of the earth. In every endeavor—from bicycle riding to drinking bouts— Hemingway tried his utmost to prevail. Where his artistic reputation was concerned, he tried, if possible, even harder.

Thus it was not especially surprising that Hemingway went on in this letter-after declaring in no uncertain terms there could be no competition between them—to compare their situation to the most famous competitive event in all literature. “Gertrude wanted to organize a hare and tortoise race,” Ernest asserted (actually, the idea of such a race came from him and not from her), “and picked me to tortoise and you to hare and naturally, like a modest man and a classicist, you wanted to be the tortoise.” Indeed Scott did, and a few years later, when he was working on the galleys of Tender Is the Night, he reverted to this metaphor in a letter to Maxwell Perkins. He was taking great pains with his revisions of the novel, Fitzgerald acknowledged, but that was his way of working. After all, he told Perkins, he was a plodder. “One time I had a talk with Ernest Hemingway and I told him, against all the logic that was then current, that I was the tortoise and he was the hare, and that's the truth of the matter, that everything that I have ever attained has been through long and persistent struggle while it is Ernest who has a touch of genius which enables him to bring off extraordinary things with facility.”

Scott then declared that he himself had “no facility,” contradicting the widely held view that he wrote too easily and without adequate conscientiousness. In fact, Fitzgerald became increasingly reluctant to stop revising his fiction as he grew older, increasingly unwilling to go into print with less than his very best. And the drafts of Hemingway's stories and novels reveal from the first a similar pattern of careful and crucially important alterations. In that sense, both Scott and Ernest were tortoising along.

In his studies of the two writers, biographer and critic Matthew J. Bruccoli consistently held that Fitzgerald “did not regard writing as competitive.” Certainly in the early years of their friendship, Fitzgerald was extraordinarily generous toward Hemingway and selflessly admiring of his work. Even then, however, people were always drawing contrasts between them. Christian Gauss, the Princeton dean who befriended such undergraduate writers as Fitzgerald, Wilson, and Bishop, looked up Scott in Paris during 1925. After a brief meeting with him and Hemingway, Gauss placed the two young authors at opposite ends of the color spectrum. “Without disrespect to him I put Hemingway down on the infrared side and you on the ultra-violet. His rhythm is like the beating of an African tom-tom—primitive, simple, but it gets you in the end.” Fitzgerald belonged at the other end of the spectrum. “You have a feeling for musical intervals and the tone-color of words which makes your prose the finest instrument for rendering all the varied shades of our complex emotional states.”

Scott could hardly have been displeased by Gauss's judgment, which obviously tilted in his favor. But once Ernest became an established figure and his own career languished, the comparisons were not always so flattering. Scott read or heard what other commentators had to say about himself and Ernest, and sometimes echoed their sentiments in his letters and notebooks. In 1931, for example, Gorham Munson in the Bookman bluntly called attention to his failed promise. “Mr. Fitzgerald has not published a novel since 1925 and his vogue has been succeeded by the vogue of Mr. Ernest Hemingway.” In a letter of his own, Fitzgerald repeated Munson's point in Munson's language: “I was silent for too long after Gatsby, and then Ernest's vogue succeeded mine.”

Fitzgerald would have had to be a saint not to harbor some resentment about this shift in their public reputation. According to Margaret Egloff, a young psychiatrist who became Scott's intimate friend during 1931, he felt that Hemingway “had more success and publicity than was deserved.” He had given Ernest a leg up, and thought that he was ungrateful. Among other things, Egloff glossed a dream of Fitzgerald's which ended in a wartime scene, an indication— she believed—of Fitzgerald's “sense of the fight to the death between men for supremacy” and of his “competitiveness with Hemingway.”