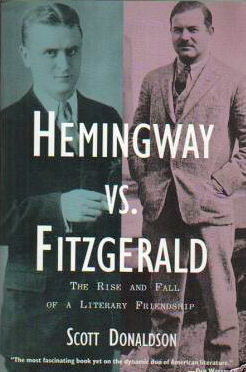

Hemingway vs. Fitzgerald: The Rise and Fall of a Literary Friendship

by Scott Donaldson

Chapter 2

Loveshocks: Jiltings

Being jilted is a rite of passage that few people, in a dating culture, are lucky enough to avoid. There is something terribly banal about rejection by a loved one, particularly by a first love. We are inclined to smile about the indignity of it, as we might smile at Reader's Digest accounts of “Life's Most Embarrassing Moments.” But the smile only emerges retrospectively, or when it is someone else who has been jilted. At the time, rejections hurt, for they strike directly at one's sense of self-worth.

One indication of the emotional cost of a jilting is that the word itself has almost vanished. College students talk of being “dumped,” and social scientists reject even that term, with its visually comic overtones. “I haven't heard anyone use jilted in twenty years,” one of them said recently. “Nowadays we talk about 'failed relationships' instead.” This psychobabbling phrase nicely skirts the issue, for if it is the relationships that fail and not the people in them, there need be no question of assigning blame, or of acknowledging one's own shortcomings and another's fickleness and cruelty. Alternatively, one can say that “things didn't work out,” as if euphemism could make the pain go away.

Fitzgerald and Hemingway suffered through their jiltings at about the same age, when they were nineteen to twenty years old. But the circumstances were very different, as were their attempts to deal with the aftershocks.

According to his Ledger, Scott Fitzgerald first heard “the name GinevraKing” when he was fourteen, and heard it again eighteen months later, in January 1913. It would be another two years before he met her, but during the interim the name resonated in his mind with the unmistakable ring of American aristocracy. “Ginevra” with its Italianate flavor promised a measure of sophistication, and she was indeed the king's daughter as in the fairy tale, only to be won by the worthiest of suitors.

Ginevra came from Lake Forest, Chicago's most socially prominent suburb. As a matter of course the family belonged to the exclusive Onwentsia Club. Her father, Charles King, pursued a successful career as a banker and—like Tom Buchanan in The Great Gatsby—was rich enough to keep a string of polo ponies. Ginevra did not need this most fortunate of backgrounds to get herself talked about. As a young girl, she earned her own reputation as a beautiful and brilliant competitor in the battle of the sexes.

Scott's former flame Marie Hersey invited Ginevra, her classmate at exclusive Westover school, to visit St. Paul during the 1914-1915 Christmas holidays. She wanted to see what would happen when Scott and Ginevra met. That meeting took place January 4, 1915, during a dinner dance at the Town and Country Club. Reluctant to abandon Chicago during the holiday's social season, Ginevra, sixteen, had just arrived in town. Scott, eighteen, was supposed to leave for Princeton that day, but postponed his train trip in order to attend the party. The evening must have gone much as Fitzgerald described it in This Side of Paradise, the highly autobiographical 1920 novel that established his reputation as an expert on and spokesman for the Jazz Age generation. In that book, as in much of his fiction, Fitzgerald displayed an uncanny knack for double vision. On the one hand, he was very much involved emotionally in the story. On the other hand, he stood back, observed, and made notes like an anthropologist immersing himself in another culture.

In his novel, Fitzgerald made his protagonist a few inches taller than himself, but otherwise the descriptions of Amory Blaine (Scott) and Isabelle Borge (Ginevra) were true to life. “Amory was now eighteeen years old, just under six feet tall and exceptionally, but not conventionally, handsome.” He had “rather a young face” with “penetrating green eyes, fringed with long dark eyelashes.” Although he lacked “that intense animal magnetism that so often accompanies beauty in men or women,” people never forgot his face.

The lack of physical magnetism troubled Fitzgerald. In the notebooks he assembled during the 1930s, he calculated his personal assets. “I didn't have the two top things— great animal magnetism or money. I had the two second things,tho', good looks and intelligence. So I always got the top girl.” This was whistling in the wind, for Fitzgerald had discovered by then that he would come in second (or lower) when matched against someone with great animal magnetism like, say, Ernest Hemingway, or against a “top girl” who had both the magnetism and the money, like Ginevra King.

“Flirt smiled from her large black-brown eyes and shone through her intense physical magnetism.” So Fitzgerald introduced Ginevra's fictional counterpart Isabelle. And as he recounted their meeting, Amory's rumored inconstancy in love rather appealed to Isabelle. The fact that “every girl there seemed to have had an affair with him at some time or other” made him a more worthy adversary in the game they would be playing. She had an almost unlimited capacity for such affairs, herself.

Amory and Isabelle confronted each other as competing performers in a contest they both enjoyed. Amory gained an early advantage with two conversational gambits. They were to be dinner partners, he announced. “We're all coached for each other.” The remark made Isabelle gasp. She had the temperament of an actress, and felt “as if a good speech had been taken from the star and given to a minor character.” Amory followed with the line about the adjective that just fit Isabelle but that he didn't know her well enough yet to reveal.

“Will you tell me—afterward?” she half whispered.

He nodded.

“We'll sit out.”

Isabelle nodded.

Isabelle regained some momentum with a compliment. “Did anyone ever tell you you have keen eyes?” she inquired, and it seemed to him that her foot just touched his under the table. During the dancing, she reigned. Boys cut in on her every few feet. She gazed up at them with that pathetic “poor little me” look Scott had instructed his sister to gain command of, and sent each one away with a squeeze of the hand intended to convey how much she had enjoyed dancing with him. Yet by eleven o'clock Amory and Isabelle had escaped the dance floor to “sit out” alone in the den upstairs. She told him about the twenty-year-old college boys who were supposedly courting her. He affected an air of blasé sophistication. Wearing masks, they both understood, was part of the game.

It grew late, and Amory turned out the electric light above their heads. He was mad for her, he said, and was going back to college for six months. Couldn't he have “just one thing to remember her by”?

“Close the door,” he barely heard her murmur. The music from outsidesounded wonderful, Isabelle thought, as she revelled in anticipation of the romantic scene to come. She envisioned “an unending succession of scenes like this: under moonlight and pale starlight, and in the backs of warm limousines and in low, cozy roadsters stopped under sheltering trees—only the boy might change, and this one was so nice.” But others burst in on them, and the moment was lost. “Damn!” Isabelle muttered to herself as she went to bed later that night. Amory had such a good-looking mouth.

In fact, Scott was the more smitten of the two. “Ginevra - Triangle year,” he headed the Ledger diary entries for the year he was eighteen. With the exception of his grades, Fitzgerald's sophomore year at Princeton was a series of successes. In February 1915, he was elected secretary of the Triangle Club. (He wrote lyrics for the Triangle musical comedies in both 1914 and 1915.) This meant he would almost certainly rise to vice president and then president of the club, if he could stay eligible. In March, he turned down three other bids to join University Cottage Club, exactly the club he had been angling for.

Things were also going well with Ginevra, that year. A month after then-first meeting in St. Paul, he traveled from Princeton to see her at Westover, but such meetings were necessarily rare. Westover kept a short leash on the fashionable girls it was in the business of preparing to lead fashionable lives. To solidify his position, Scott wooed Ginevra through the mails, writing long letters almost daily. Usually designed to entertain, the letters were accompanied by drawings and bits of doggerel and dialogue. Occasionally, though, he chastised her for encouraging other suitors. There were probably more of these than he imagined. At the time, Ginevra later admitted, she “was definitely out for quantity not quality in beaux.” Scott was “top man” for the moment, but she still coveted attention from others and was not about to change her ways. She had never asked to be placed on a pedestal, she reminded him. Besides, it was her cohort of admirers that attracted him in the first place.

In June 1915 he took Ginevra to see Nobody Home on Broadway, and danced with her afterward at the Ritz hotel's Midnight Frolic. He saw her again in Chicago, on his way back to St. Paul for the summer. Observing Ginevra in her own milieu, Scott began to understand the handicaps he faced in courting her. The notation in his Ledger for that visit reads: “Stopping off in Chicago. Midge Muir. House Party. Jimmy Johnston. Deering: I'm going to take Ginevra home in my electric.” Midge Muir effectively vanished, and there exists no account of the house party. More would be heard of Jimmy Johnston, the Harrison Johnston who was to become United States amateur golf champion. It was Deering's offhand remark/boast that troubled Scott, who had himself no automobile either gas- or electric-powered to take home the young lady he liked to think of as his girl. The distance between Ginevra's overprivileged surroundings and his own was driven home further when Courtney Letts told him that Deering, the boy with the electric, was “as poor as a church mouse.”

Scott spent much of the summer in Montana, on the ranch of Sap Donahoe, his classmate and friend both at Newman school and Princeton. “No news from Ginevra,” he somewhat ominously observed in his Ledger for August 1915. Back in college, he launched into a junior year “of terrible disappointments & the end of all college dreams. Everything bad in it was my own fault.” First off, he flunked a makeup exam in mathematics, and became ineligible for his Triangle Club office. “There were to be no badges of pride, no medals, after all,” he realized. His career as a leader of men was over. Throughout the fall, he continued to neglect his studies. In December, he and the dean reached an agreement that it would be better for him to leave and try again the following year. “Went home early sick,” he laconically noted in his Ledger, without mentioning his academic difficulties.

During those despairing months, Fitzgerald “lived on the letters” he was writing to Ginevra. They had dinner together in Waterbury, Connecticut, one evening in October 1915, and he did not see her again until the following summer. Meanwhile, Ginevra was “fired” from Westover for flirting with a boy from the window of her room after the senior dance. The next morning headmistress Mary Hillard (who was, incidentally, the aunt of the poet Archibald MacLeish) summoned Ginevra to her office, delivered the standard cautionary tale about “foxes in the henhouse,” and dismissed her from school. Perhaps it was on the ride back to Chicago that she encountered Jimmy Johnston. Scott's Ledger for April includes “Ginevra & Jimmy on the train.” That cryptic comment may prefigure Dick Diver's jealousy in Tender Is the Night when he hears about Rosemary Hoyt's intimacy with a traveling companion on a train trip. Almost everything about Ginevra King found its way into his stories and novels, eventually.

In August 1916, Ginevra invited Scott for a second visit on her home grounds, and this time it was even more forcibly brought home to him that in courting this golden girl, he was reaching beyond his grasp. The shorthand of his Ledger recreated the experience: “Lake Forest. Peg Carry. Petting Party. Ginevra. Party. The bad day at the McCormicks. The dinner at Pegs. Dissapointment. Mary Buford Pierce. Little Marjorie King & her smile.Beautiful Billy Mitchell. Peg Cary stands straight. 'Poor boys shouldn't think of marrying rich girls.'”

Nothing has come to light about the bad day at the McCormicks or Mary Buford Pierce. Everything else in the cryptic catalogue signifies. Margaret (Peg) Cary was a close friend of Ginevra's. With Courtney Letts and Edith Cummings, they made up the “Big Four” debutantes of the time, girls so legendary for their beauty that they were known by that designation for the rest of their lives. In the late 1970s, I met a fellow from Lake Forest at the Yale Club bar in New York City, and asked him if possibly he had heard of “the Big Four,” who would have been at least a decade his senior. He had indeed— everyone in Lake Forest had—and he could tell me about their subsequent marriages and divorces as well.

The generic “Petting Party” Fitzgerald made famous in This Side of Paradise, revealing to a shocked older generation “how casually their daughters were accustomed to be kissed.” The Popular Daughter of the day (P.D.) was a good deal more liberal with her favors than the “belle” who preceded her, he explained. “The 'belle' was surrounded by a dozen men in the intermissions between dances. Try to find the P.D. between dances, just try to find her.” Like as not she would be inside someone's limousine, with the boy of the moment. Amory Blaine “found it rather fascinating to feel that any popular girl he met before eight he might quite possibly kiss before twelve.”

“Little Marjorie King,” Ginevra's younger sister, suggested that it might have been their father Charles King who made the devastating remark that “tp]oor boys shouldn't think of marrying rich girls.” Certainly those were the sentiments of his generation and class on the subject. By most standards of measurement, of course, Scott Fitzgerald was not a poor boy. But in the scale of Lake Forest, which Scott thought of as “the most glamorous place in the world,” he was poor all right. Especially so in comparison to “Beautiful Billy Mitchell,” who like Charles King was rich enough to maintain polo ponies and who was to marry the beautiful Ginevra King two years later.

Scott's courtship of Ginevra did not end after his visit to Lake Forest, but it might as well have. There remained the fiasco of the Princeton-Yale game in October 1916. Ginevra and Peg Cary came to Princeton for the game and the associated parties. When Scott and Peg's date delivered them to the train station in New York, the girls said their good-byes, and then rendezvoused with two Yale boys—oh, the disloyalty—who were secreted behind the pillars. “Final break with Ginevra,” Scott noted in January 1917, but she did not disappear from hisLedger, not quite. In June 1917: “Ginevra engaged?” and “Girl at show resembled G.K.” In September 1917: “Minnekahda [Minikahda] Club. 'Oh Ginevra.'” Finally in July 1918, the month Scott met Zelda Sayre: “Ginevra married.” September 1918: “Fell in love [with Zelda] on the 7th.”

Zelda delayed committing herself to Scott until he could demonstrate sufficient capacity to support her. When she broke off their engagement on those grounds, he wrote in a Crack-Up essay of 1936, it seemed to be “one of those tragic loves doomed for lack of money.” In the end he won Zelda back by publishing a novel and selling a story to Hollywood. But, he pointed out, “since then I have never been able to stop wondering where my friends' money came from, nor to stop thinking that at some time a sort of droit de seigneur might have been exercised to give one of them my girl.” The images of both Zelda and Ginevra must have conflated in his mind as he wrote those words, though the courtships hardly resembled each other. Zelda came from an old Southern family, but she was by no means rich. And she always took Scott seriously as a suitor, even when she was putting him off. Ginevra, apparently, never did.

“He was mighty young when we knew each other,” Ginevra said of Scott in a 1974 interview, adding that she hadn't “singled him out as anything special.” He was one of several boys she was carrying on romances with, and in retrospect, by no means the most memorable of the group. She couldn't even remember kissing Scott, Ginevra said. She threw away the hundreds of letters he sent her, and when he had her letters typed up and bound into a booklet, she disposed of those as well. She did write him a farewell letter before her marriage in 1918. It was one of quite a few she had to write, for she “was engaged to two other people” at the time. Multiple engagements were easy enough to manage during the war, she explained, “because you'd never get caught. It was just covering yourself in case of a loss.” For Ginevra, Scott was an engaging competitor in the courtship game, nothing more. She was not to blame if he converted the game into a passionate quest for an unattainable ideal.

Looking back on their relationship, Ginevra wouldn't have changed a thing. At no time did Scott measure up to her idea of someone she could marry, for he came from a different social universe. Just how different is emphasized in a Chicago newspaper article about her that Fitzgerald pasted in his scrapbook. This society page feature amounts to a puff piece about Ginevra (then Mrs. William H. Mitchell III), whose portrait had recently been completed “by the great painter Sorine.” The Ginevra of this account, identified as one of “These Charming People,” had a “truly natural beauty” unenhanced by rouge ormascara. She was vibrant and energetic, and when she laughed, which was often, her enormous deep brown eyes sparkled. But Mrs. Mitchell was still more to be admired for her way of life “which combine[d] a tremendously gay amusing time with a thoughtful organized existence.” She was “a grand and courageous horsewoman” who followed the seasons to Aiken and Palm Beach and Santa Barbara—resorts where the wealthy took the sun and rode horses. Back in Lake Forest, she ran her own house “to the queen's taste” and supported every worthy charity, in particular St. Luke's Hospital in Chicago.

That kind of life, Scott knew, was beyond his means, and so he invested it with glamour. When he heard about Ginevra's divorce in 1936, he sent her a copy of The Beautiful and Damned and asked her on the flyleaf to identify which character had been modelled after her. “They were all such bitches,” she said, that she didn't feel like guessing. Yet on a trip to Santa Barbara in 1937, she summoned him from Hollywood for a luncheon meeting. Scott was nervous as a schoolboy about the prospect. “She was the first girl I ever loved,” he wrote his daughter Scottie, “and I have faithfully avoided seeing her up to this moment to keep the illusion perfect, because she ended up by throwing me over with the most supreme boredom and indifference.” Maybe he shouldn't go, he halfheartedly proposed to Scottie. Of course he did.

At the beginning, Scott and Ginevra got along extremely well during then-lunch in Santa Barbara. Then, characteristically, he botched the reunion by falling off the wagon and out of favor. Despite a number of phone calls in the next few days, Ginevra refused another meeting. She was still “a charming woman,” he reported to Scottie. “I'm sorry I didn't see more of her.” In going out of his life yet again, Ginevra gave him one more failure to cherish, one more humiliation to remember and hang on to, like the list of “Snubs” he carefully preserved in his notebooks, lest they go away.

The only mementos Ginevra had of Scott when the revival of Fitzgerald's literary reputation was getting underway were his Triangle Club pin (“if that's of use to anyone”) and a couple of snapshots. She sent those to biographer Arthur Mizener in 1947. She was not, herself, a fan of Scott's writing. “It was quite a while” after their youthful romance, as she put it, “before he developed into what people consider a good writer.”

How did Fitzgerald react to his rejection by Ginevra King? According to Ginevra, he sent her a brief “insulting” note when she announced her wedding plans. Beyond that report and the brief notes in his Ledger, there is surprisingly little documentation. He did not retire from the social whirl, exactly. The namesof a number of girls appear in the Ledger entries after the January 1917 “Final break with Ginevra,” leading up to that of Zelda Sayre. Still, there can be no doubt that he fell in love with Zelda on the rebound. The hurt of losing Ginevra did not disappear. He wrote about the pain of that loss again and again.

“Mostly, we authors must repeat ourselves,” Fitzgerald commented in a 1933 essay. “We have two or three great and moving experiences in our lives… Then we learn our trade, well or less well, and we tell our two or three stories— each time in a new disguise—maybe ten times, maybe a hundred, as long as people will listen.” One of those stories for Fitzgerald, the one most often repeated, is that of the poor boy hopelessly in love with the rich girl. It is the story of Amory Blaine and Rosalind Connage in This Side of Paradise, of Dexter Green and Judy Jones in “Winter Dreams,” of Jay Gatsby and Daisy Fay Buchanan in The Great Gatsby. “The whole idea of Gatsby,” he said, “is the unfairness of a poor young man not being able to marry a girl with money. This theme comes up again and again because I lived it.”

Writing about that emotional trauma did not make it go away. You'll lose it if you talk about it, Hemingway's Jake Barnes maintains, but that depends on how you talk about it. In the case of Fitzgerald, even though each of his stories ends in disillusionment for the spurned suitors, he could not bring himself to condemn the characters who elicited the disillusionment. Rosalind is culpably selfish in turning down Amory, Judy lures and drops suitors with a callous recklessness, Daisy will not abandon a hollow but financially secure marriage even for love. Yet as he depicts them, his golden girls remain largely untarnished. Intellectually Fitzgerald understood that “nine girls out of ten marry for money.” Emotionally he refused to hate them for doing so, if they were as beautiful and unwinnable as Ginevra King of Lake Forest.

***

What went wrong with Ernest Hemingway and Agnes von Kurowsky had nothing to do with social position, but still there was a barrier between them— a barrier of age.

Much has been made of the wound Hemingway suffered at Fossalta di Piave shortly before midnight on July 8,1918. He arrived in Italy five weeks earlier, to serve as an ambulance driver for the Red Cross. The ambulance service was not thought of as particularly dangerous. Ernest, in fact, was the firstAmerican to be injured in Italy (one other had been killed). On the night he was wounded, he volunteered to pass out chocolate and cigarettes to the troops at the front. He was only eighteen, just a year out of Oak Park High School, and like many another immature lad in battle thought of himself as exempt from the laws of mortality. That illusion exploded with the mortar shell that the Austrians' Minenwerfer launched across the river.

Hundreds of shrapnel fragments ripped into Hemingway's legs. He thought he was dying. He could not move, he fought for breath, he felt his soul flutter out of his body like a handkerchief in the wind. When the initial shock abated, he managed to stagger a hundred and fifty yards to the first aid dugout, and to carry a wounded soldier on his back. En route he was struck by two machine-gun bullets in his right leg. The Italians awarded him a medal for gallantry under fire.

Hemingway did not soon outlive that night at Fossalta. In dreams and nightmares, in fiction and in fact, he returned to the scene time and again. One of his characters makes the pilgrimage in order to defecate on the exact spot of the wounding. For years to come, Ernest could not sleep without a light burning in the room.

Psychologically oriented critics have seized on the wounding in Italy as a key to interpreting Hemingway's life and work. As a result, they maintained, he was repeatedly compelled to prove his courage and face down his fears, in the process reliving—and once more miraculously surviving—the terrible trauma. Hemingway lived long enough to read such speculations and dismiss them as in his view absolute nonsense, but they take on a certain credibility when considered in the context of his life and writing. Wounds leave scars, and not all of them heal completely. That much at least was true not only of his physical wounding in World War I, but of the emotional injury inflicted by Agnes von Kurowsky.

Here is the way it was. The badly wounded Ernest was brought to the handsome five-story house on the Via Manzoni in Milan then serving as a makeshift hospital for the American Red Cross. From the roof, you could see the massive Duomo, the Galleria with its shops and restaurants, and the famous opera house La Scala. Hemingway was one of the first patients to arrive. Even lying flat on his back, he projected a winning animal vitality. He was terrified that the doctors might amputate his leg, yet refused to feel sorry for himself. Red Cross officers came to call and went away full of admiration for his high spirits and good humor. Among them was Captain Jim Gamble, a wealthy thirty-six-year-old who took a particular interest in Ernest, and not only because he was in charge of the volunteers for the “rolling canteens” to serve the front-line troops. Then as always, Hemingway easily commanded male friendship.

Women were new to him, however. Physically, he was shedding his adolescent awkwardness and becoming for the first time highly attractive to the opposite sex. Unlike Fitzgerald, he had little experience in courtship. There were no serious girlfriends in high school. Whenever possible, his mother arranged for Ernest to accompany his sister Marcelline to social gatherings. He may, like his autobiographical character Nick Adams, have copulated in the woods with a native American girl, but perhaps not. Visiting an Italian house of prostitution with other young Red Cross volunteers, Ernest turned red with embarrassment when one of the whores accosted him.

The nurses in Milan soon made a favorite of Hemingway. They smiled at his boyish exuberance, and conspired in silence when he drank from the bottle of cognac secreted in his quarters. He was also admired as a patient who had been wounded at the front. The nurses “liked to exhibit him… as their prize specimen of a wounded hero,” as fellow patient Henry Villard—who was recovering from jaundice and malaria—remarked with a degree of asperity. He and Ernest, among others, were rivals for the affection of Agnes von Kurowsky.

Agnes was tall and attractive, with chestnut-brown hair. Cheerful and lively, she was like Ernest full of energy and had a considerable appetite for adventure. At twenty-six she was seven and a half years his senior, and independent for her age, having worked in the Washington, D.C., public library before going to nursing school at Bellevue in New York City. Eager to see the world, she joined the Red Cross nursing service early in 1918. Italy was her first overseas post. She arrived in Milan only a few days before Hemingway. An angel had come to him, he wrote home, “in the form of a beautiful night nurse named Agnes,” who gave him a hot bath and sent him off to the first good night's sleep he'd had in months.

Agnes was not without experience in affairs of the heart. When she came to Italy, she was officially engaged to the doctor she'd left behind in New York. She did not let that deter her from seeking out new places and making new friends. As she later admitted, she was “pretty fickle” at the time.

Agnes did not mind night duty, and as Ernest's night nurse cared for him during the difficult early weeks when he was operated on twice and his leg immobilized in a cast. By the middle of August, he was wildly in love with her, and she was receptive enough to come to his room in the early hours of the morning for intimate conversation. As their romance developed Agnes and Ernest held hands more or less openly and wrote daily notes to each other during the hourswhen they were apart. Matters had gone far by the time the crisp fall weather came to north Italy. Then circumstances conspired to keep them apart, perhaps abetted by the powers-that-be in the Red Cross.

On September 24, Ernest and another patient set out for a week's holiday at Stresa, on Lake Maggiore. On October 15, Agnes was transferred to Florence to care for a victim of “the Spanish fever.” In late October Ernest went to the Monte Grappa front, contracted jaundice, and returned to the hospital in Milan in the comforting custody of Jim Gamble. Sometime early in November Gamble offered Hemingway a year's stay in Italy, all expenses paid, as his secretary and companion. On Armistice Day, November 11, Agnes came back to Milan. Nine days later she and another nurse were assigned to Treviso where the flu was raging among American troops. Ernest visited her there December 9. During the Christmas holiday, Ernest stayed with Jim Gamble at his villa in Taormina, Sicily. He and Agnes met one final time before he sailed from Genoa to New York on the S.S. Giuseppe Verdi on January 6, 1919. It was understood between them that they were to be married when she came back to the United States. Soon thereafter she was posted to Torre di Mosta, where she met and fell in love with an Italian officer named Domenico Caracciolo. On March 7 she mailed Ernest the letter breaking off their relationship.

In later years Agnes invariably contended that she and Ernest had not been lovers. This assertion is largely borne out in the diary she kept from June 12 to October 20, 1918, which was edited and published by Villard and James Nagel in 1989. (This diary provided the basis for In Love and War, a disastrously bad motion picture starring Sandra Bullock and Chris O'Donnell.) The sometimes passionate letters she wrote to Ernest in the fall of 1918 appear to tell a different story, however. He saved those letters, while Agnes burned his at the insistence of Caracciolo: just like Scott and Ginevra.

While she was in Florence and Treviso, Hemingway wrote her almost every day, and she replied nearly as often. She yearned for them to be together, she wrote from Florence, so that she could nestle in the hollow space he made for her face and then go to sleep with his arm around her. Then she added a promise: “I love you more and more and know what I'm going to bring you when I come home.”

To avert suspicion about their relationship—Red Cross nurses were not supposed to have love affairs with their patients—she posted some of her letters to the Anglo-American Officers Club in Milan instead of the hospital. “This is our war sacrifice, bambino mio, to keep our secrets to ourselves.” Right now, shepointed out, the “older world” wouldn't understand, and “would make very harsh criticisms.” After the war, they could tell everyone.

The difference in their ages runs like an unacknowledged undercurrent through her correspondence. Ernest is her bambino mio, her dear boy. He is “Kid” to her “Mrs. Kid.” Agnes dispenses advice and praise as to a younger person sorely in need of flattery and approval. She admires the beautifully tailored British uniform he's acquired in Milan. She is proud of him when he promises to cut back on his drinking. An ironic motif concerns her fear that Ernest might abandon her as she had abandoned her doctor fiancé in New York. “I never pined for anybody before in my life,” she wrote him from Treviso. “I never imagined anyone else could be so dear and necessary to me… Don't let me gain you only to lose you. I love you, Ernie.”

During the mid-November week when both were in Milan, the two lovers solidified their marriage plans. On November 23, Ernest wrote his sister Marcelline that he'd always wondered what it would be like to “meet the girl you will really love always and now I know.” Ag loved him too, and so he knew for sure who he was going to marry. In retrospect, Agnes said that she'd only consented to their engagement to keep Ernest away from Jim Gamble, who seemed to be sexually interested in him. Ernest, she thought, would never be “anything but a bum… if he started traveling around with someone else paying the expenses.” She and Ernest became engaged soon after Gamble proposed the yearlong holiday to Hemingway. When the captain suggested a journey to Madeira as an added inducement, Agnes warned Ernest against going. If he did go, she was afraid he'd never “be somebody worth while. Those places do get in one's blood, & remove all the pep & 'go' and I'd hate like everything to see you minus ambition.” Sometimes, she went on, she wished that they might be able to marry in Italy, but that was a foolish idea. Ernest did not go to Madeira, and soon after his December 9 reunion with Agnes in Treviso, he agreed to return to the States at the first opportunity. In order, as Ernest saw it, to start earning for their marriage. Also in order, as Agnes viewed it, to avoid becoming a bum and a sponger, if not worse. “When I was with Jessup [another nurse],” she wrote him, “I wanted to do all sorts of wild things—anything but go home—and when you [were] with Captain Gamble you felt the same way. But I think maybe we have both changed our minds—and the old États-Unis are going to look très, très bien to our world-weary eyes.”

In the light of this triangular complication, it is extremely significant that Ernest never told Agnes—or anyone else—about his trip to see Gamble inTaormina over Christmas. He even constructed a tall tale to account for his activities in Sicily. At the first place he stopped overnight, he wrote his friend Eric Dorman-Smith, the hostess hid his clothes and kept him to herself for a week. His only complaint was that he'd seen very little of the country. Agnes's letters from Treviso said nothing about his upcoming trip to Sicily. Instead she lamented that she could not get away from her duties, so they would not be together for their “first Christmas.” Just make believe “you're getting a gift from me (as you will someday),” she wrote. “And let me tell you I love you.” In closing, she raised once more the possibility that their love might not last. “I miss you more and more, and it makes me shiver to think of your going home without me. What if our hearts should change?”

In the context of her loving letters, it seems likely that in encouraging Ernest to reject Gamble's offer of an expenses-paid year in Europe and return to the United States, Agnes hoped both to save him from his own worst instincts and to save him for herself. But she may also have begun to have second thoughts about the age gap between them. At their last meeting before he sailed home, she and Ernest quarreled about when she would be following. To calm him down, Agnes agreed to come as soon as possible, but she was not really ready to give up her stay in Europe. The issue lay between them across the ocean.

The letters from Agnes to Ernest over the next two months were obviously calculated to prepare him for the end and must have been exquisitely painful to read.

“Well, good night, dear Kid,” she signed off one of her first missives to Oak Park. “A rivederla, carissimo tenente, suo cattiva ragazza, Agnes.” She was, cheerfully enough, “his naughty girl,” but this hardly conveyed a passionate commitment to their love. After she was transferred from Treviso to run the small Red Cross field hospital in Torre di Mosta, Agnes scaled back her letters from twice a week to once every two weeks, and with each one sounded less and less like Ernest's future wife.

Ernest, meanwhile, continued to save money toward their marriage. He must have sensed the increasing chill in Agnes's correspondence, but he was not prepared to admit it to himself—or to the close friends he'd told about their marriage plans. One of these was Bill Smith, in a December 13 letter from Milan. “Bill this is some girl and I thank God I got crucked so I met her,” Hemingway wrote. He couldn't understand what she saw in him “but by some very lucky astigmatism she loves me… So I'm going to hit the States and start working for the Firm. Ag says we can have a wonderful time being poor together.” All he had to do now was “hit the minimum living wage for two and lay up enough for sixweeks or so up North and call on you for service as best man.” He only had fifty more years to live, and felt that every moment he spent away from “that Kid” was wasted.

Agnes to Ernest, February 3-5, 1919:

Agnes's enthusiasm is not so apparent. “My future is a puzzle to me, and I'm sure I don't know how to solve it. Whether to go home, or apply for more foreign service is the question just now.” (Hadn't they settled that question ?) “Of course, you understand this is all merely for the near future, as you will help me plan the next period, I guess” (she guessed!)… “I'm getting fonder, every day, of furrin' parts” (she'd answered the question already?) “Goodnight old dear, Your weary but cheerful Aggie.” (Why didn't she sign off “I love you” anymore?)

Agnes to Ernest, February 15, 1919:

The unreliable Italian mail system had broken down, and she had not seen a letter from him for a while. It was “hard work writing letters when you have none to answer,” she complained. (Hard work? Writing to him?) She'd had guests for dinner at Torre di Mosta, including the “tenente medico [who was] the funniest and brightest one yet.” (Was this a rival?) “I have a choice of staying a year in Rome, but I'm thinking of going to the Balkans so I'm rather undecided as yet… work is going to be very dull at home after this life.” (So she had made up her mind to stay overseas another year: wasn't this the same girl who'd sent him home to wait for her?)

Agnes to Ernest, March 1, 1919:

Now there were too many letters from him. “I got a whole bushel of letters from you today, in fact haven't been able to read them all yet.” (She hadn't read them?) “I can't begin to keep up with you, leading the busy life I do.” (Her career came first, did it?) Aside from work, she was having the time of her life and never lacked for excitement. (With whom?) She had a star shell pistol and lots of cartridges to fire off on dark nights. (Alone?) She had learned to smoke and to play “a fascinating gambling game” called 7 1/2. (Who taught her?) She had to admit she was far from the perfect being he thought her. “I'm feeling very cattiva tonight, so goodnight, Kid, and don't do anything rash, but have a good time. Afft. Aggie.” (She wasn't his “cattiva ragazza” now, merely feeling naughty 5,000 miles away, and even the disappointing “Affectionately” came in abbreviated form.)

Ernest to Jim Gamble, March 3, 1919:

Ernest could hardly have failed to detect the warning signals Agnes was flashing across the seas. He decided to make contact with the benefactor she'd been protecting him from. Perhaps that bridge had not burned down. His long letter to Gamble didn't get around to mentioning Agnes until the sixth paragraph. “The Girl doesn't know when she will be coming home,” Ernest admitted, but he'd been saving money against the day. He had “$172 and a fifty buck Liberty Bond in the Bank already… Maybe she won't like me now I've reformed, but then I'm not very seriously reformed.”

News of Agnes shared time in this letter with reports of Bill Horne and Howie Jenkins and others who had been in the ambulance service with Hemingway and Captain Gamble. The principal theme, however, had to do with Ernest's deeply felt regret that he was stuck in Oak Park instead of liberated in Sicily with Jim, his old “Chief.” “Every minute of every day,” Ernest wrote, he kicked himself for not being there. In memory he called back the sight “of old Taormina by moonlight and you and me, a little illuminated some times, but always just pleasantly so, strolling through that great old place and the moon path on the sea and Aetna fuming back of the villa.” The thought of what he might have had made him “so damn sick” that he poured himself a glass, and thinking of the two of them sitting in front of the fire after dinner, offered Jim a transatlantic toast: “I drink to you Chief. I drink to you.”

“You know I wish I were with you,” he closed the letter.

Agnes to Ernest, March 7, 1919:

This was the letter he had been afraid of. Significantly, Agnes addressed him as “Ernie, dear boy.” Even before Ernest left Italy, she wrote, she'd been trying to convince herself that theirs was “a real love-affair.” She'd only given in (consented to the engagement?) to keep him “from doing something desperate” (accepting Gamble's invitation?). Now, two months later, she was still “very fond” of him, but “more as a brother than a sweetheart.”

And not only a brother but a younger brother, for the real thrust of her argument was that Ernest was too young for her. Agnes realized that she had made him care for her, and was sorry about that from the bottom of her heart. “But I am now & always will be too old, and that's the truth, & I can't get away from the fact that you're just a boy—a Kid.” (She was no longer “Mrs. Kid, ” however.) She expected to be proud of him some day, but it was “wrong to hurry a career.” It made no practical sense for a twenty-seven-year-old woman with a profession to marry a nineteen-year-old youth with no occupation or college education or immediate prospects. She'd tried to tell him that when they quarreled at their last meeting, but he'd acted “like a spoiled child” and so she stopped.

The closing paragraph unveiled the rival (Domenico Caracciolo) her previous letters had hinted at. “Then—& believe me when I say this is sudden for me, too—I expect to be married soon. And I hope & pray that after you have thought things out, you'll be able to forgive me & start a wonderful career, & show what a man you really are.” (Or at least, what a man he could become.)

“Ever admiringly & fondly, Your friend—Aggie,” she signed off.

Hemingway went through a number of reactions to his jilting. He sank into a morass of sorrow, he converted the hurt to anger, he affected a stance of philosophical wisdom, he determined to prove the jilter wrong (Won't she be sorry, though?), and he tried to exorcise the experience by writing about it.

When Agnes's break-up letter arrived, Ernest zombied around the house in Oak Park in an attitude of leaden despair. Within days, however, he managed to write Bill Horne a curiously two-toned letter about the rejection, appealing for sympathy on the one hand and on the other adopting a pose as expert on affairs of the heart. “She doesn't love me, Bill,” he commences. “She takes it all back. A 'mistake.' One of those little mistakes, you know. Oh, Bill, I can't kid about it, and I can't be bitter because I'm just smashed by it… All I wanted was Ag. And happiness and now the bottom has dropped out of the whole world.”

Then he put aside his sorrow, amazingly, to make a sweeping generalization. As if to repudiate Agnes's reason for rejecting him—his relative immaturity (which he does not reveal to Horne)—Ernest donned the mantle of experience. The split would never have happened, he asserted, if he'd stayed with Agnes in Italy. “You, meaning the world in general, teach a girl—no, I won't put it that way—that is you make love to a girl and then you go away. She needs someone to make love to her. If the right person turns up, you're out of luck. That's the way it goes.” Hemingway could rarely resist playing the expert, and in doing so for Home's benefit, sought to regain a measure of his damaged authority. If only he, the teenaged tutor, had not taught the older Agnes the joys of lovemaking, she would not have succumbed to another. It was his fault. He was too skillful an instructor.

Still, he longed to do something to ventilate his frustration and anger. He claimed, in his only fictional rendering of the jilting, that in retaliation he contracted a dose of gonorrhea from a girl who worked in a Chicago department store. He told a friend that he burned out Agnes's memory “with a course ofbooze and other women.” Perhaps these tales were true, perhaps not. What is certain is that he became angrier and angrier the more he thought about how she had cheated him out of a wonderful year in Italy. As he wrote Jim Gamble, her letter came as “a devil of a jolt because I'd given up everything for her, most especially Taormina.”

In mid-June he had a chance to take a measure of revenge. Agnes's romance with Caracciolo had ended short of the altar, when his family took the view that she was “an American adventuress.” According to Hemingway, Caracciolo was the heir to a dukedom, but this may have been exaggeration. Elsewhere he promoted his rival from Tenente (first lieutenant) to Major, and reassigned him to the crack Arditi. No ordinary man could have taken Agnes away, no matter how starved for love Ernest had left her. Anyway, as he wrote Howie Jenkins, there was nothing he could do for poor Agnes now. “I loved her once and then she gypped me.” The news of Agnes's misfortune did not entirely assuage his anger. When he heard that Agnes was coming back to the States, Ernest expressed his devout wish that she might trip on the gangplank and knock out her front teeth.

The charge that he was a boy, a kid, a spoiled child still rankled. He set out to demonstrate that she was wrong about that, but the demonstration took time. Two years after the jilting, in the summer of 1921, he married Hadley Richardson, a woman who at almost eight years his senior was a few months older than Agnes. (Jim Gamble complicated that courtship as well, by inviting Ernest to join him overseas, this time in Rome.) Eighteen months later, in November 1922, he wrote Agnes about how far he had progressed. He was traveling around Europe, as she had longed to do, as a roving foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star Weekly. He was headquartered in Paris, a city that she loved. He was married to Hadley, who was a fine musician and shared his love of the outdoors. His first book—Three Stories and Ten Poems—was to be published soon. Did she begin to realize what she'd missed?

This letter does not survive, but much of it can be reconstructed from Agnes's reply. It may be that he made a proposal of some sort about a meeting between them. At the Lausanne conference in the same month he wrote her, he told the famous journalist Lincoln Steffens that he was prepared to leave Hadley if Agnes would come back. If so, her response of December 22 was not encouraging. She filled him in on her activities during the intervening years. Like him, she had wanted to break “somebody or something” when she was jilted by her Italian fiancé. She was delighted to hear about his book. “How proud I will be,some day in the not-very-distant future to say 'Oh yes, Ernest Hemingway-Used to know him quite well during the war.'”

But Agnes went on to insist that events had proven her right in ending their “comradeship.” She reiterated the point about the difference in their ages, softening the blow this time by stressing her antiquity instead of his youth. “May I hope for an occasional line from you?” she inquired, but there was no coquetry, no hint of resuming their romance. It was just that she and Ernest had been “good friends” once, and “[f]riends are such great things to have.” Then she offered him a firm handclasp, and closed with “best wishes to you & Hadley… Your old buddy Von (oh excuse me, it's Ag).”

Ernest must have concluded that no matter what he achieved, he could not change Agnes's mind. She thought him too young for her when he was nineteen, and she still thought so four years later, never mind that he had married and moved to Paris and launched a promising career. Six months later, he spelled out his lingering resentment in “A Very Short Story.”

This story is manifestly autobiographical. Wounded soldier and nurse fall in love, he returns to the States, she proves faithless and writes him a goodbye letter. In its earliest draft, “A Very Short Story” remains sympathetic to the nurse as someone who succumbs to loneliness and muddy weather and the wiles of an Italian lover. But in its final draft, written after Ernest received Agnes's December 1922 letter, the tone becomes heavily sardonic at her expense. The story strains our credulity. “Ag” (excuse me, “Luz,” as Hemingway altered the name to avoid a possible libel suit) is too cruel, too unfeeling, too selfish, while the wounded patient-narrator (who is given no name at all) is too good, too noble, too unfairly wronged to be convincing.

The most interesting thing about the story, from a psychological standpoint, is that it drastically distorts the contents of the “Ernie, dear boy” letter. Luz, in the story, wrote the narrator that she regarded theirs as “only a boy and girl affair,” and, again, as “only a boy and girl love.” Agnes wrote Ernest that their romance was doomed because it was a boy and woman affair. This issue Hemingway concealed, in print and out. Looked at dispassionately and from a distance, Agnes von Kurowsky's 1919 letter breaking off her relationship with Ernest bears a strong family resemblance to Grace Hemingway's 1920 letter scolding her son about his overdrawn mother-love bank account. In their different ways, both women were telling him to grow up.

***

In a 1988 article on “Love Survival: How to Mend a Broken Heart,” psychologist Stephen Gullo and journalist Connie Church contend that the emotional effect of losing a lover through rejection parallels that of losing a loved one to death. In each case, the one left behind is liable to suffer through the same stages of shock, anger, grief, blame, and denial before reaching acceptance.

A common if misguided reaction to jiltings, according to the authors, is that of revenge loving, or the reckless pursuit of replacements for the departed lover. Copulating with shop girls in taxicabs, as Hemingway claimed he did, would certainly qualify. On a more long-term basis, so would the engagements and marriages that both Fitzgerald and Hemingway embarked upon in less than two years' time. Interestingly, both men married women who resembled those who had turned them down. Zelda Sayre was petite like Ginevra, and like her somewhat younger than Scott Fitzgerald and much sought after by other men. Like Agnes, Hadley Richardson was tall, responsible, and substantially older than Ernest Hemingway. But there was one crucial difference. The women who married the two young writers chose to believe in them, and their future.

Another device for surviving rejection was to loose one's fury on the faithless jilter—not getting mad, getting even. In effect, this is what Hemingway did in his attack on Agnes in “A Very Short Story.” It took him four years to get his frustration down on paper, but he only needed to do it once. (Some have suggested that Agnes also served as a model for Catherine Barkley in A Farewell to Arms, a nurse who falls head over heels in love with Frederic Henry and dies in the attempt to bear his child. But the real nurse and the fictional one share almost no qualities whatever, and of course Catherine does not jilt Frederic.)

In Fitzgerald's case, by way of contrast, the rejection by Ginevra—and later, the same rejection or very nearly so by Zelda—provided him with a basic donnée of his fiction. He took the hurt, hugged it to his bosom, and would not let it expire.

Fitzgerald fell prey to the worst possible reaction cited in the “Love Survival” piece: idealizing the girl who turned him down, and obsessively thinking about her. As a sovereign remedy to such self-demeaning behavior, Gullo and Church recommend that spurned suitors get in the habit of writing things down. Keep a diary in which you can vigorously express your feelings (including anger), and you'll feel better. Or make lists of the worst qualities of the jilter, and you'll feel much better. Or if you're capable and so inclined, write out your story, making the one who abandoned you the villain of the piece, and maybe the hurt will go away.

Hemingway, as it happened, found it easier to write about his physical wound in World War I than about his emotional one, and the process of writing about what happened at Fossalta may have helped cure him of his trauma. Twenty years later, he behaved with conspicuous courage during the Spanish Civil War. Twenty-six years later, during the hell of the Hurtgen forest, he struck General Buck Lanham as the bravest man he ever met.

Unlike the Austrians, Agnes von Kurowsky administered a hurt that time could not heal. Hemingway wrote a story about it, not one of his best, but did not get rid of it that way. Instead, he internalized the lesson that Agnes—and his mother—had taught him: that those who love can be betrayed. After that knowledge, he made sure he did not put himself at emotional risk. Hemingway had many friends, and broke off most of those friendships, sometimes viciously. He was married four times, and at the end of the first three of them he was responsible for the divorce, with a new wife waiting in the wings while the final scenes with the old one were being played out. He also behaved abominably to his fourth and last wife; only the extraordinary staying power of Mary Hemingway kept that union from dissolving as well.

The jilting by Agnes von Kurowsky, and his mother's censure, may have been the most important of the several serious wounds that fate was to deal Ernest Hemingway. In his young manhood, they drove him toward achievement as he sought to belie the charge of immaturity. And throughout his life, they compelled him to sever ties before friend or lover could strike a blow to the heart. Even mortar shells, he had discovered, were less painful.

Sources

FSF and Ginevra King:

FSF, Ledger, 165, 167, 169-173. FSF, Notebooks, 205. SD, Fool, 48-52. FSF, Paradise, 58-71. Lehan, Craft of Fiction, 92-93, 189. FSF, Crack-Up, 77. Friskey, “Visiting the Golden Girl,” 10-11. Martha Blair, “These Charming People,” FSF Scrapbook, PUL. FSF to Scottie Fitzgerald, October 8, 1937, Life in Letters, 338. FSF, “One Hundred False Starts,” Afternoon, 132. Lehan, Craft of Fiction, 95. FSF to Annabel Fitzgerald, ca. 1915, Life in Letters, 8.

EH and Agnes von Kurowsky:

Baker, Life Story, 43, 46-56. SD, “The Jilting of Ernest Hemingway,” 661-673. Villard and Nagel, editors, Hemingway in Love and War, 48, 118-119, 135. EH to Smith, December 13, 1918, SL, 20. EH to Gamble, March 3, 1919, SL, 21-23. EH to Jenkins, 16 June 1919, SL, 25. SD, “'A Very Short Story' as Therapy,” 99-105. Gullo and Church, “Love Survival: How to Mend a Broken Heart,” 51-53, 77.

Next Chapter 3 A Friendship Abroad

Published as Hemingway Vs. Fitzgerald: The Rise And Fall Of A Literary Friendship by Scott Donaldson (Woodstock, Ny: Overlook P, 1999).