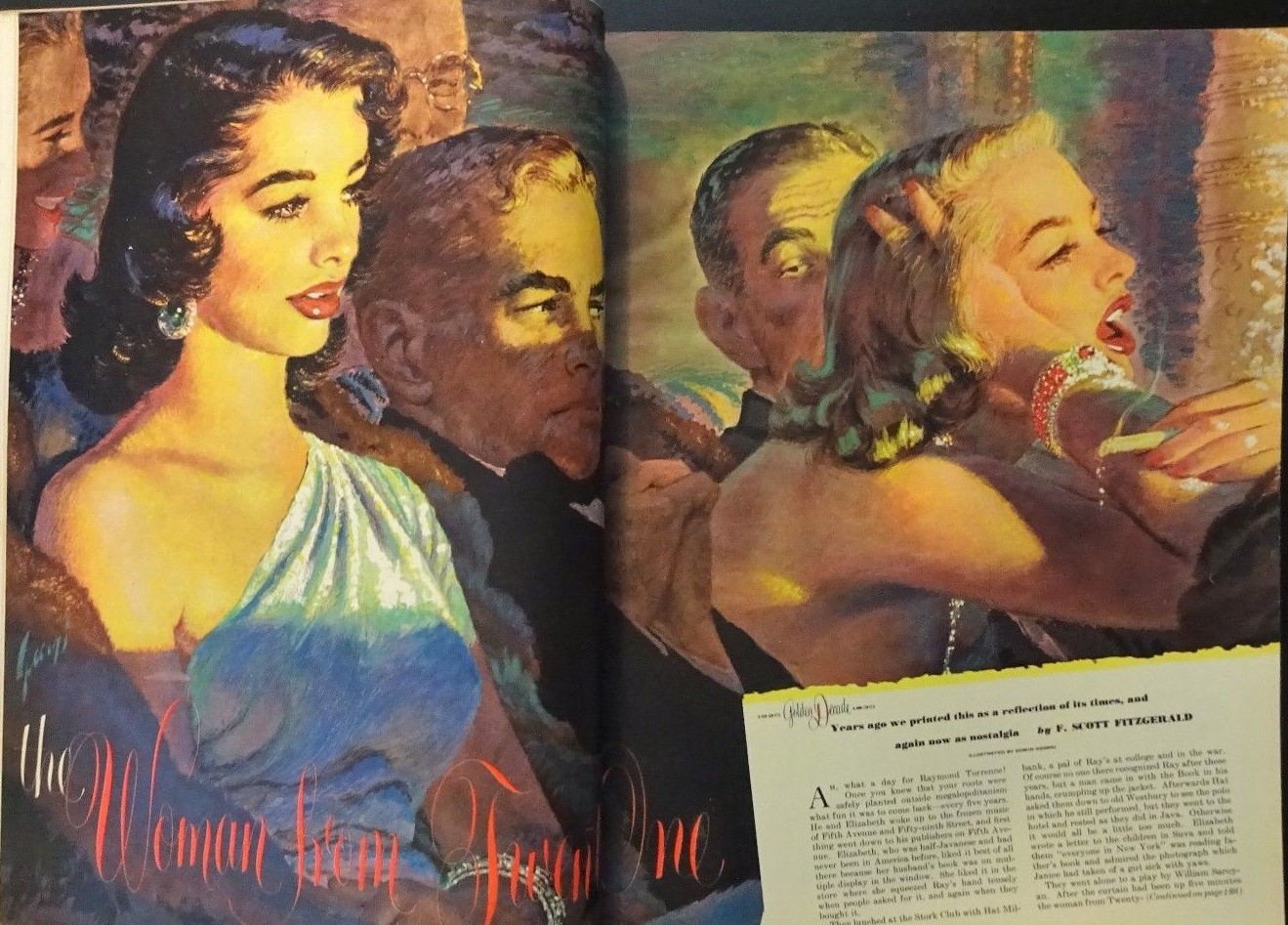

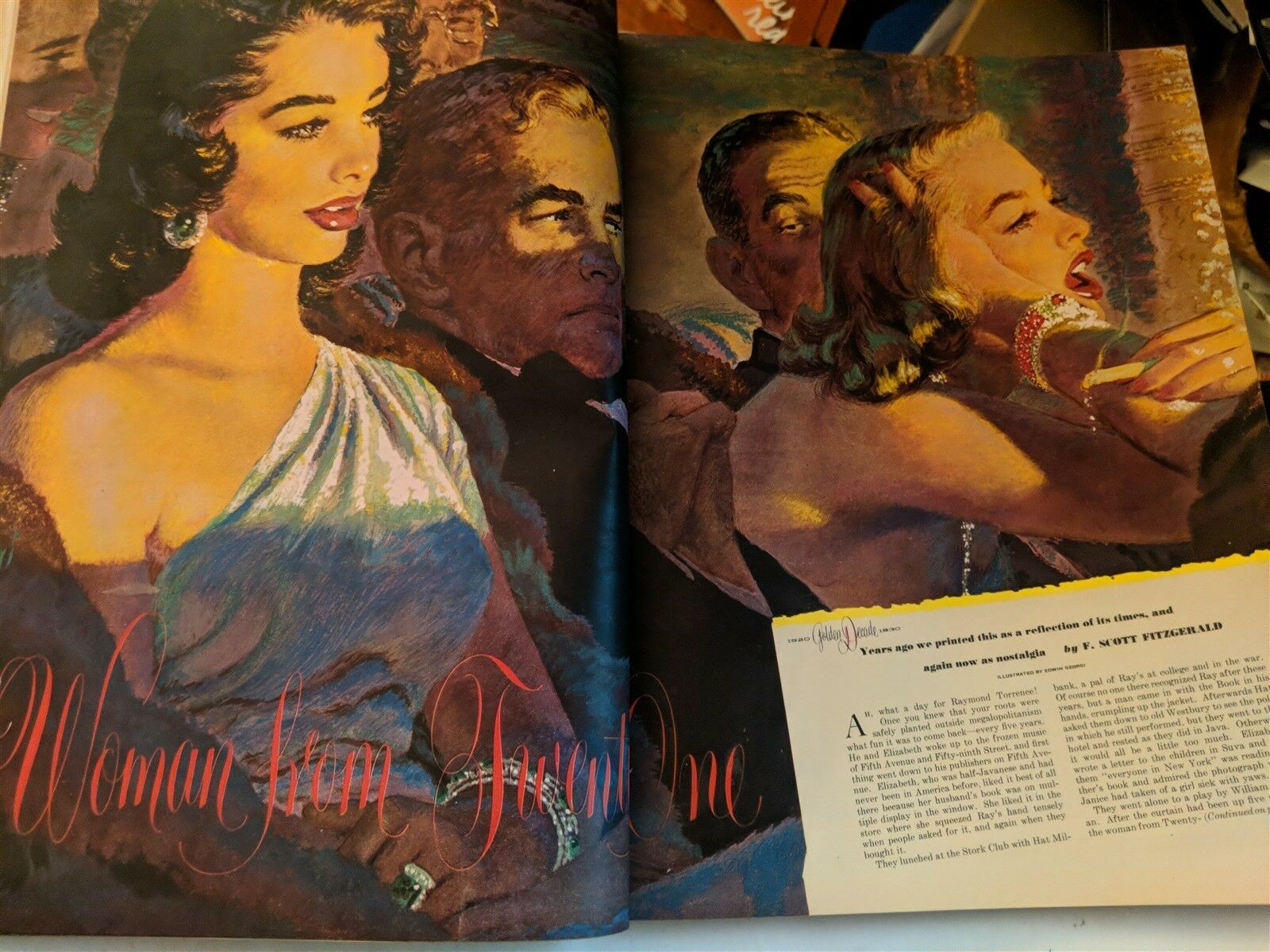

The Woman from “21”

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Ah, what a day for Raymond Torrence! Once you knew that your roots were safely planted outside megalopolitanism what fun it was to come back—every five years. He and Elizabeth woke up to the frozen music of Fifth Avenue and Fifty-ninth Street, and first thing went down to his publishers on Fifth Avenue. Elizabeth, who was half Javanese and had never been in America before, liked it best of all there because her husband's book was on multiple display in the window. She liked it in the store where she squeezed Ray's hand tensely when people asked for it, and again when they bought it.

They lunched at the Stork Club with Hat Milbank, a pal of Ray's at college and in the war. Of course no one there recognized Ray after these years but a man came in with the Book in his hands, crumpling up the jacket. Afterwards Hat asked them down to old Westbury to see the polo in which he still performed, but they went to the hotel and rested as they did in Java. Otherwise it would all be a little too much. Elizabeth wrote a letter to the children in Suva and told them “everyone in New York” was reading father's book and admired the photograph which Janice had taken of a girl sick with yaws.

They went alone to a play by William Saroyan. After the curtain had been up five minutes the woman from “21” came in.

She was in the mid-thirties, dark and pretty. As she took her seat beside Ray Torrence she continued her conversation in a voice that was for outside and Elizabeth was a little sorry for her because obviously she did not know she was making herself a nuisance. They were a quartet—two in front. The girl's escort was a tall and good-looking man. The woman leaning forward in her seat and talking to her friend in front, distracted Ray a little, but not overwhelmingly until she said in a conversational voice that must have reached the actors on the stage:

“Let's all go back to ‘21’.”

Her escort replied in a whisper and there was quiet for a moment. Then the woman drew a long, long sigh, culminating in an exhausted groan in which could be distinguished the words, “Oh, my God.”

Her friend in front turned around so sweetly that Ray thought the woman next to him must be someone very prominent and powerful—an Astor or a Vanderbilt or a Roosevelt.

“See a little bit of it,” suggested her friend.

The woman from “21” flopped forward with a dynamic movement and began an audible but indecipherable conversation in which the number of the restaurant occurred again and again. When she shifted restlessly back into her chair with another groaning “My God!” this time directed toward the play, Raymond turned his head sideways and uttered a prayer to her aloud:

“Please.”

If Ray had muttered a four-letter word the effect could not have been more catalytic. The woman flashed about and regarded him—her eyes ablaze with the gastric hatred of many dying martinis and with something more. These were the unmistakable eyes of Mrs. Richbitch, that leftist creation as devoid of nuance as Mrs. Jiggs. As they burned with scalding arrogance—the very eyes of the Russian lady who let her coachman freeze outside while she wept at poverty in a play—at this moment Ray recognized a girl with whom he had played Run, Sheep, Run in Pittsburgh twenty years ago.

The woman did not after all excoriate him but this time her flop forward was so violent that it rocked the row ahead.

“Can you believe—can you imagine—”

Her voice raced along in a hoarse whisper. Presently she lunged sideways toward her escort and told him of the outrage. His eye caught Ray's in a flickering embarrassed glance. On the other side of Ray, Elizabeth became disturbed and alarmed.

Ray did not remember the last five minutes of the act—beside him smoldered fury and he knew its name and the shape of its legs. Wanting nothing less than to kill, he hoped her man would speak to him or even look at him in a certain way during the entr'acte—but when it came the party stood up quickly, and the woman said: “We'll go to ‘21’.”

On the crowded sidewalk between the acts Elizabeth talked softly to Ray. She did not seem to think it was of any great importance except for the effect on him. He agreed in theory—but when they went inside again the woman from “21” was already in her place, smoking and waving a cigarette.

“I could speak to the usher,” Ray muttered.

“Never mind,” said Elizabeth quickly. “In France you smoke in the music halls.”

“But you have some place to put the butt. She's going to crush it out in my lap!”

In the sequel she spread the butt on the carpet and kept rubbing it in. Since a lady lush moves in mutually exclusive preoccupations just as a gent does, and the woman had passed beyond her preoccupation with Ray, things were tensely quiet.

When the lights went on after the second act, a voice called to Ray from the aisle. It was Hat Milbank.

“Hello, hello there, Ray! Hello, Mrs. Torrence. Do you want to go to ‘21’ after the theatre?”

His glance fell upon the people in between.

“Hello, Jidge,” he said to the woman's escort; to the other three, who called him eagerly by name, he answered with an inclusive nod. Ray and Elizabeth crawled out over them. Ray told the story to Hat who seemed to ascribe as little importance to it as Elizabeth did, and wanted to know if he could come out to Fiji this spring.

But the effect upon Ray had been profound. It made him remember why he had left New York in the first place. This woman was what everything was for. She should have been humble, not awful, but she had become confused and thought she should be awful.

So Ray and Elizabeth would go back to Java, unmourned by anyone except Hat. Elizabeth would be a little disappointed at not seeing any more plays and not going to Palm Beach, and wouldn't like having to pack so late at night. But in a silently communicable way she would understand. In a sense she would be glad. She even guessed that it was the children Ray was running to—to save them and shield them from all the walking dead.

When they went back to their seats for the third act the party from “21” were no longer there—nor did they come in later. It had clearly been another game of Run, Sheep, Run.

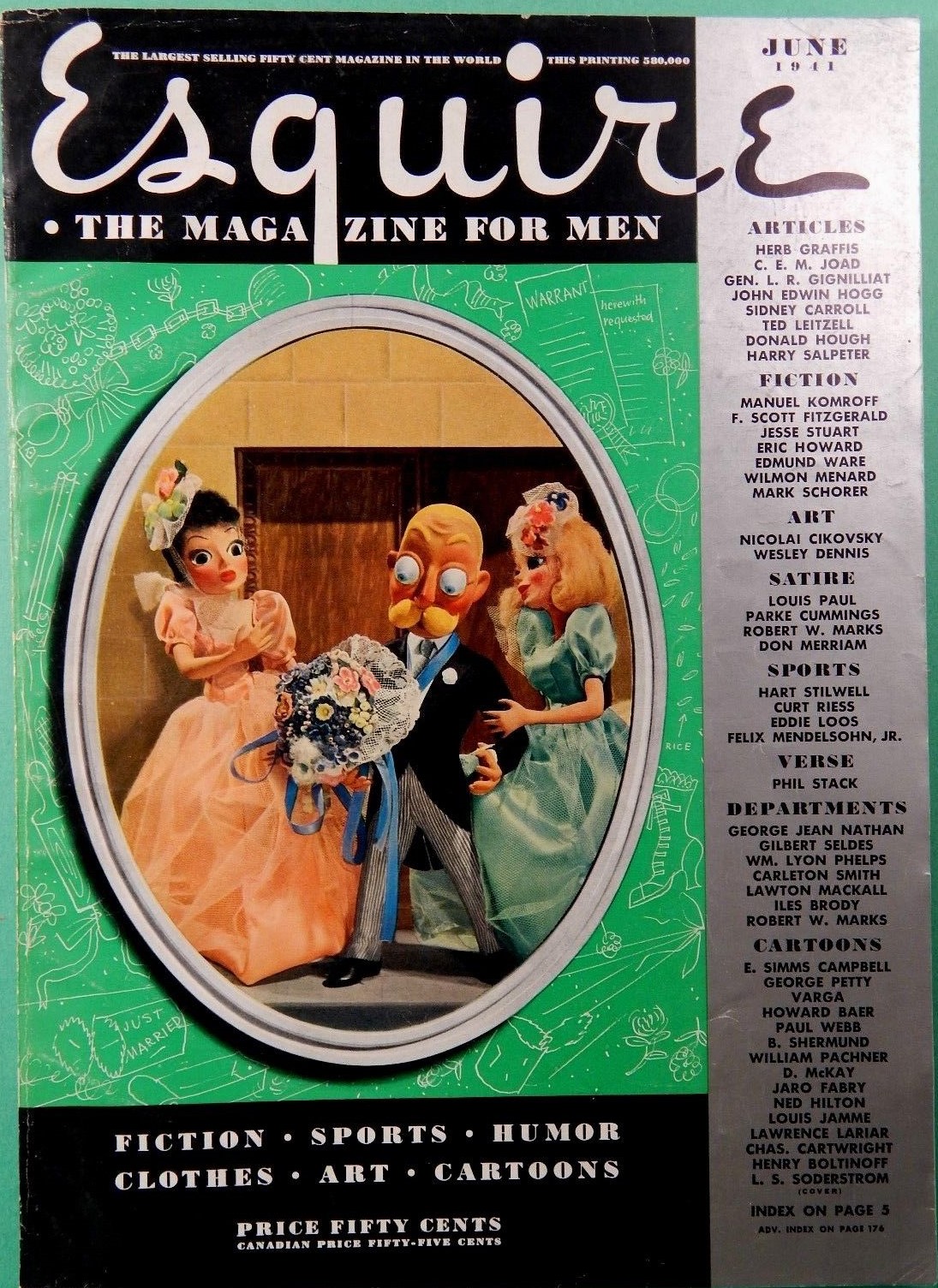

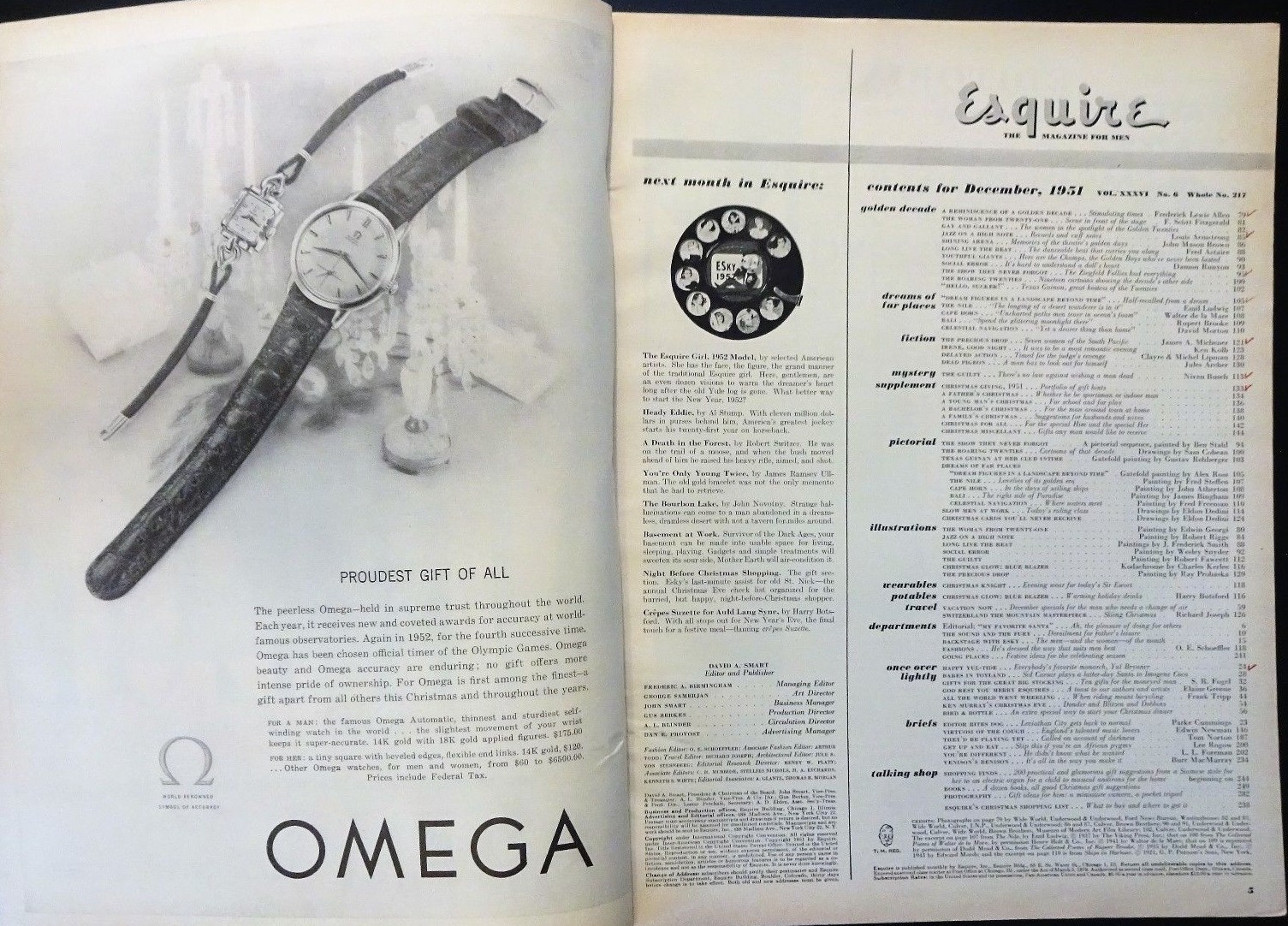

Published in Esquire magazine: first publication in (June 1941); and second publication in (December 1951).

No illustrations (first publication); illustrations by Edwin Georgi (second publication).