The Honor of the Goon

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

When Bomar Winlock was at Kennesaw Military Academy he was best known for falling downstairs. This was no idle slip of the foot, for with the aid of some convenient double joints he had perfected it to an art. The technique was as follows:

When visitors came to the school Winlock, loitering about the entrance, would graciously offer to show them to the Major’s office on the second floor. At the top of the stairs he would point out the office, bow a polite good-by, turn as if to descend and then Wham! Slap! Bang! Down the stairs, head over heels, rear over teakettle, would plunge the unfortunate boy, his broken body hesitating realistically at the landing and then resuming its dive to death—Slap! Bang! Wham!—by now to the accompaniment of cries and even screams from the observers above.

When he reached the bottom, confederates approached and after solicitous conversation:

“Is he dead?”

“No, he’s still breathing.”

—they would pick him up and bear him out of sight, presumably to the infirmary.

The brilliance of his career at this role so intoxicated Bomar that he pursued it upon proper occasions through freshman year in college, after which a growing sobriety made him suppress it except on a few irresistible occasions. One of these had to do with the Goon.

The Goon, roughly speaking, was from the Far East, and was often referred to at State Reserve College as a Chink, though actually she was a Malay. An eager, gentle-faced girl with a slight limp, she had scarcely been a week at State Reserve when Bomar, much as another man might crave a drink, was seized with an irrepressible impulse to fall down the stairs of the Curriculum Building. It was a good fall, steep steps, and even coeds who had seen him before gave little yelps of terror and dismay. But of all who saw him only Ella Lei Chamoro ran toward his supine, motionless body to give succor.

She was so sincere about it, so possessed by pity in a wide-eyed Oriental way, that some premonition of maturity must have stirred in Bomar, so that instead of playing the game out he arose and walked rather sheepishly away. From that moment he disliked her emphatically; it was he who named her the Goon. There were other goons—fat girls, ugly girls, unattractive girls generally, but Ella Lei Chamoro was the goons of goons.

A very particular adolescent cruelty seemed to sharpen itself for her like a snickersnee. Imaginary faults and excesses were attributed to her; she was practically ostracized at all unofficial and most official occasions and her face which had once been childish and receptive, developed by junior year certain unattractive lines of hurt, panic and suspicion that even the famous Oriental imperturbability did not conceal.

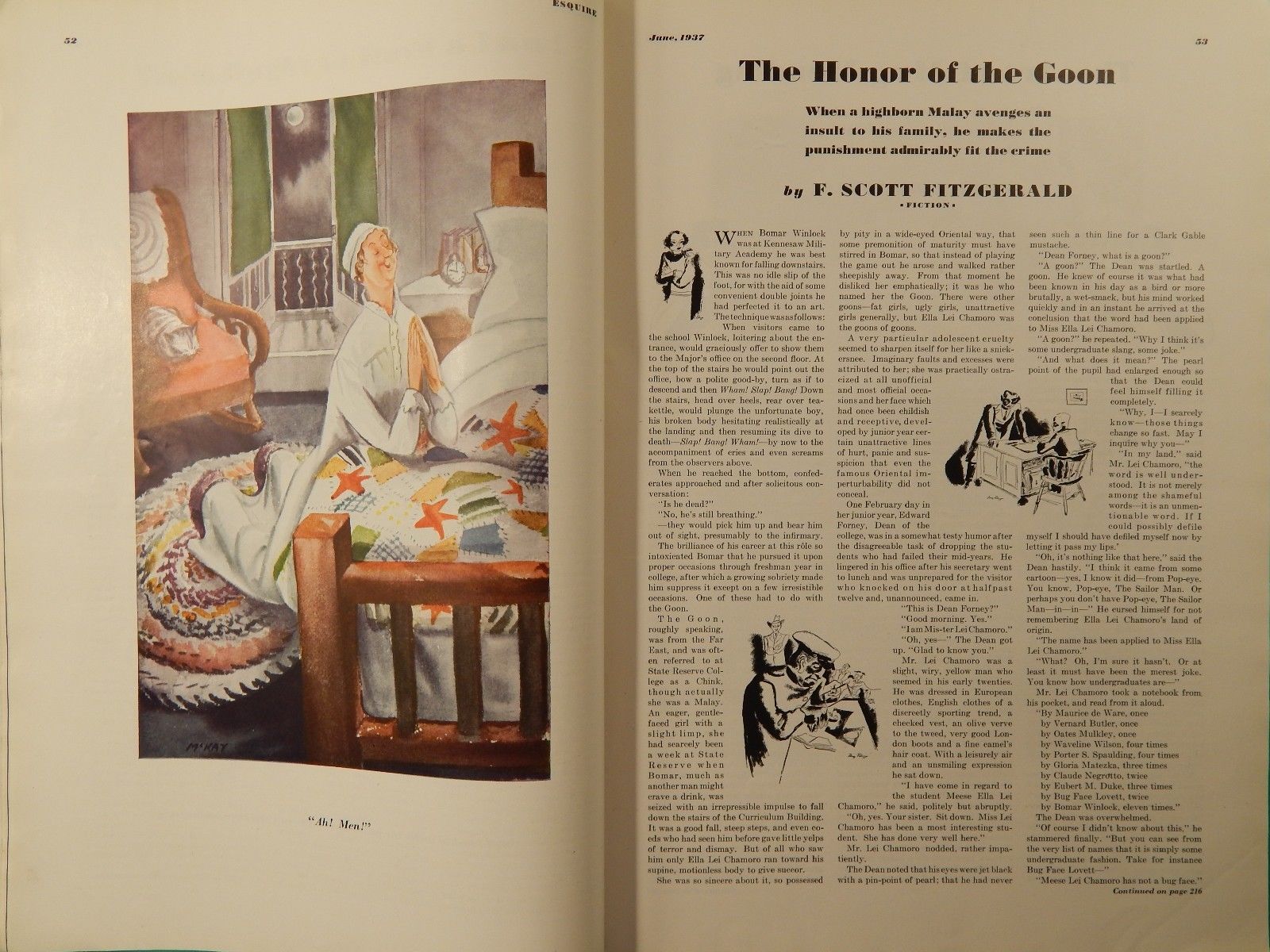

One February day in her junior year, Edward Forney, Dean of the college, was in a somewhat testy humor after the disagreeable task of dropping the students who had failed their mid-years. He lingered in his office after his secretary went to lunch and was unprepared for the visitor who knocked on his door at half past twelve and, unannounced, came in.

“This is Dean Forney?”

“Good morning. Yes.”

“I am Mister Lei Chamoro.”

“Oh, yes—” The Dean got up. “Glad to know you.”

Mr. Lei Chamoro was a slight, wiry, yellow man who seemed in his early twenties. He was dressed in European clothes, English clothes of a discreetly sporting trend, a checked vest, an olive verve to the tweed, very good London boots and a fine camel’s hair coat. With a leisurely air and an unsmiling expression he sat down.

“I have come in regard to the student Meese Ella Lei Chamoro,” he said, politely but abruptly.

“Oh, yes. Your sister. Sit down. Miss Lei Chamoro has been a most interesting student. She has done very well here.”

Mr. Lei Chamoro nodded, rather impatiently.

The Dean noted that his eyes were jet black with a pin-point of pearl; that he had never seen such a thin line for a Clark Gable mustache.

“Dean Forney, what is a goon?”

“A goon?” The Dean was startled. A goon. He knew of course it was what had been known in his day as a bird or more brutally, a wet-smack, but his mind worked quickly and in an instant he arrived at the conclusion that the word had been applied to Miss Ella Lei Chamoro.

“A goon?” he repeated. “Why I think it’s some undergraduate slang, some joke.”

“And what does it mean?” The pearl point of the pupil had enlarged enough so that the Dean could feel himself filling it completely.

“Why, I—I scarcely know—those things change so fast. May I inquire why you—”

“In my land,” said Mr. Lei Chamoro, “the word is well understood. It is not merely among the shameful words—it is an unmentionable word. If I could possibly defile myself I should have defiled myself now by letting it pass my lips.”

“Oh, it’s nothing like that here,” said the Dean hastily.“I think it came from some cartoon—yes, I know it did—from Pop-eye. You know, Pop-eye, The Sailor Man. Or perhaps you don’t have Pop-eye, The Sailor Man—in—in—” He cursed himself for not remembering Ella Lei Chamoro’s land of origin.

“The name has been applied to Miss Ella Lei Chamoro.”

“What? Oh, I’m sure it hasn’t. Or at least it must have been the merest joke. You know how undergraduates are—”

Mr. Lei Chamoro took a notebook from his pocket, and read from it aloud.

“By Maurice de Ware, once

by Vernard Butler, once

by Oates Mulkley, once

by Waveline Wilson, four times

by Porter S. Spaulding, four times

by Gloria Matezka, three times

by Claude Negrotto, twice

by Eubert M. Duke, three times

by Bug Face Lovett, twice

by Bomar Winlock, eleven times.”

The Dean was overwhelmed.

“Of course I didn’t know about this,” he stammered finally.“But you can see from the very list of names that it is simply some undergraduate fashion. Take for instance Bug Face Lovett—”

“Meese Lei Chamoro has not a bug face.”

“No, of course she hasn’t. I meant—”

“And Meese Lei Chamoro is not a goon.”

.“Of course not. Your sister is—”

“She is not my sister. She is a relative. I wish to know just how they treat one who is a so-called goon.”

“Treat them? Why, no special way. I still haven’t made it clear—”

“Is it not true that they do not escort them to dances, nor dance with them if they are there, nor ask them to eat in their girls’ fraternities, nor walk with them on the street?”

“Why, no. That is—”

“Is it not true that they fall down whole flights of steps and when one who is termed a goon comes up kindly to help they make a joke of her?”

“Why, no—I didn’t know about that. I haven’t been told—”

“—that she is made a pariah and lower than a slave, that she is neglected and scorned?”

It really was hot in the room, the Dean thought. He went and opened a window, letting in a breath of sunny February. Fortified by this he tried to take over the situation.

“In an American institution,” he said,“a foreigner is naturally an exception, and must seem a little strange. But I should not like to think—”

“Nor should I,” said Mr. Lei Chamoro dryly. “Nor should I be here save that her father is ill. I see you know little of what goes on here.

“You should, no doubt, be immediately removed to make place for a more competent man. So if you will kindly give me the address of the student Bomar Winlock I shall no longer trouble you.”

“Why, certainly—certainly,” said the Dean thumbing his catalogue.“But I assure you—”

After his visitor had gone the Dean went to his window and watched a great black limousine crinkle stones down the gravel drive.

“Goon,” he repeated to himself.“A goon, a goon, a goon.”

II

For the midwinter dance Bomar Winlock and his roommate were importing a girl from the nearest city, and they were getting ready—a cocktail mixture was developing, flowers were being arranged, and a pile of feminine cabinet studies lay on the table, ready to be put temporarily out of sight. There were quite a few visitors on the campus today and when the Oriental gentleman knocked at the door they merely thought it was someone who had got the wrong room.

“I am searching for one Bomar Winlock.”

“That’s me.”

The visitor took a long look at him with eyes that Bomar observed were black as coals, with a little diamond glint in the center of each.

“What can I do for you?” asked Bomar.

“I should like to see you alone.”

“This is my roommate, Mr. Mulkley.”

Mr. Lei Chamoro looked at Mr. Mulkley not quite as long as he had looked at Bomar.

“Oates Mulkley?” he inquired.

“Why, yes.”

“You had better stay here.”

Both young men regarded Mr. Lei Chamoro with surprise which began to be mingled with a faint apprehension as they hastily reviewed recent sins.

“Well, what is it?” demanded Bomar.

“You have seen fit to cause a certain discomfort to my relative Meese Ella Lei Chamoro.”

“What do you mean?” Bomar demanded.“Say, what is this? I’ve hardly ever said hello to her.”

“That might be one of the methods employed.”

“I don’t get you. I hardly know Ella Lei Chamoro. What do you want me to do? Take her out and perch?”

Suddenly he realized that this was not at all the right note. The diamond in Mr. Lei Chamoro’s eyes had enlarged a little and now he was in them as definitely as Dean Forney had been fifteen minutes before.

“You’ve got the wrong man,” Bomar said.“I never had anything to do with your sister.”

“Then you never referred to her as a goon—or as the Goon?”

“The Goon? Why, of course I—why, a lot of people use that expression, I don’t know whether I ever did or not.”

“That is a lie, Mis-ter Bomar Winlock,” said Lei Chamoro. “Eleven times within her knowledge you have applied this word to my relative.”

Bomar and Oates Mulkley exchanged a glance, deriving a certain truculence from the other’s presence.

“I’m not used to being called a liar,” said Bomar.

“No? Well, are you used to being called a low cur, discourteous to female strangers in your land? Faugh! Your room stinks of stale cowards’ sweat.” He raised his voice slightly,“Fingarson!”

Even as the two young men took a step toward Mr. Lei Chamoro the door opened and a huge, slab-jawed chauffeur came in, drawing off his gloves. Bomar stopped in his tracks.

“What is this, anyhow? What—!”

“All right, Fingarson.”

Bomar took a step backward, then another step, then he literally flew backward as the Norwegian swung a huge fist against his jaw, slamming him against the piano where his shoulder played a crashing discord as he fell.

Oates, forewarned, tried to interpose a table between himself and the giant, then reached ineffectually for a vase of flowers but the onslaught was too sudden. He took a blow full in the mouth, went down, struggled to his knees and went down again, saying, “Hey, what the hell!” and spitting blood from his lip. Fingarson looked at Bomar but the latter had been seriously jarred and lay groggy where he had fallen.

Lei Chamoro addressed them calmly as if they were in full possession of their faculties.

“For the honor of my relative it is necessary that you be degraded and I had thought of a burn from the curling tong of Meese Lei Chamoro. But here’s something ready to hand. Fingarson, take those pictures on the table out of their frames. It will give me great pleasure to defile the likenesses of their female relatives.”

Bomar, his head still reeling, watched uncomprehendingly; Oates stirred and said with all the menace he could put in his voice:

“You lay off those photographs. They aren’t relatives.”

“The girls you love then,” said Lei Chamoro.“Fingarson, now I want you to spit carefully upon the face of this one with the lovely comb in her hair. Then with your finger I want you to rub the face, just the face—so—until it’s no longer there—you see.”

With a curse Oates staggered to his feet but this time Fingarson acted so quickly and efficaciously that during the rest of the proceedings he saw only blurred figures and heard voices that were dun and far away. Bomar, who was alive enough to see this second debacle, remained discreetly on the floor.

“But these are all young flappers,” caviled Lei Chamoro. “Look in the bedroom, Fingarson.” And when the chauffeur returned,“Now this is better—this woman of sixty or so. A pleasant, kindly face—it shouldn’t have to look at this dog.”

“That is my mother,” said Bomar hollowly,“and she’s dead. Please—”

Lei hesitated momentarily, then he spat and with his finger made a white rough smudge where the face had been.

“It’s better like this,” he said, regarding it.“And here is the father, too. Yes, certainly a resemblance—it will be a pleasure to defile it, though I had thought you were fathered by some stray peddler. And here—well, it is Jean Harlow, and in such company. We will spare her, for surely this is a picture you wrote for. Surely she’d never look at you.”

“Shall I hang them up, sir?” asked Fingarson when the mutilation was complete.

“Certainly,” said Lei Chamoro.“Shame should be a public thing. Their friends will say ’Here are two young men who are fond of speaking of young ladies as goons. And just look at all the goons they choose to have around their room’.”

He smiled at his joke, for the first time. Then the pin points of light in his eye grew large again as he addressed Bomar.

“I regret that the law doesn’t permit me to slit your throat. In future when you pass my relative, Meese Ella Lei Chamoro, I prefer you to cross the street lest she breathe the foul odor that I detect on you.”

He took a last look around.

“Toss the flowers from the window, Fingarson. They must be unhappy among those who torture women.”

***

The black limousine had been three minutes gone from, the gravel drive before there was any activity in the room. Bomar was the first to rise and walk dumbly around the sudden tomb.

“Say, that was awful,” he said, “awful!”

“Why didn’ you do something?” said Oates.“I couldn’t fight that big guy alone.”

“I was out. Anyhow I bet that Chink had a knife up his sleeve—did you hear what he said about cutting my throat?”

“What are you going to do about it?”

“Go over and complain to the Dean, that’s what I’m going to do. You know that’s burglary—entering a man’s room and destroying his property like photographs. A lot of those photographs I can’t replace.”

He stared aghast at the wall, “God, they look awful. We’ve got to take them down.”

“Well, let’s get going,” said Oates. “And let me tell you, what I’m going to do to that Goon will be plenty.”

Bomar glanced uneasily at the window.

“He said he was coming back.”

“No, he didn’t.”

“Yes, he did.”

“Next time we’ll be ready for him.”

“You bet.”

Bomar regarded himself in the mirror.

“Say, how am I going to explain this face to the twitches?”

“Oh, hell,” said Oates, getting to his feet with a groan. “Tell them you fell down stairs.”

Published in Esquire magazine (June 1937).

Illustrations by (unknown Esquire artist).